"Happiness, not gold or prestige, is the ultimate currency.”

You don’t want to be rich—you want to be happy. Although the mass media has convinced many Americans that wealth leads to happiness, that’s not always the case. Money can certainly help you achieve your goals, provide for your future, and make life more enjoyable, but merely having the stuff doesn’t guarantee fulfillment.

This book will show you how to make the most of your money, but before we dive into the details, it’s important to explore why you should care. It doesn’t do much good to learn about compound interest or high-yield savings accounts if you don’t know how money affects your well-being.

If personal finance were as simple as understanding math, this book wouldn’t be necessary; people would never overspend, get into debt, or make foolish financial decisions. But research shows that our choices are based on more than just arithmetic—they’re also influenced by a complex web of psychological and emotional factors.

This chapter gives you a quick overview of the relationship between money and happiness. You’ll also learn techniques for escaping the mental traps that make it hard to be content with what you have. As you’ll see, you don’t need a million bucks to be happy.

The big question is, “Can money buy happiness?” There’s no simple answer.

“It seems natural to assume that rich people will be happier than others,” write psychologists Ed Diener and Robert Biswas-Diener in Happiness (Blackwell Publishing, 2008). “But money is only one part of psychological wealth, so the picture is complicated.”

There is a strong correlation between wealth and happiness, the authors say: “Rich people and nations are happier than their poor counterparts; don’t let anyone tell you differently.” But they note that money’s impact on happiness isn’t as large as you might think. If you have clothes to wear, food to eat, and a roof over your head, increased disposable income has just a small influence on your sense of well-being.

To put it another way, if you’re living below the poverty line ($22,050 annual income for a family of four in 2009), an extra $5,000 a year can make a huge difference in your happiness. On the other hand, if your family earns $70,000 a year, $5,000 may be a welcome bonus, but it won’t radically change your life.

So, yes, money can buy some happiness, but as you’ll see, it’s just one piece of the puzzle. And there’s a real danger that increased income can actually make you miserable—if your desire to spend grows with it. But that’s not to say you have to live like a monk. The key is finding a balance between having too little and having too much—and that’s no easy task.

Note

A recent article in the Journal of Consumer Research showed that, in general, our feelings for material purchases fade more quickly than they do for experiential purchases. Material goods depreciate: The day after you buy something, it’s usually worth less than you paid for it. Experiences, on the other hand, appreciate: Your memories of the things you do—vacations you take, concerts you go to—become fonder with time because you tend to recall the positives and forget the negatives.

American culture is consumption-driven. The media teaches you to want the clothes and cars you see on TV and the watches and jewelry you see in magazine ads. Yet studies show that people who are materialistic tend to be less happy than those who aren’t. In other words, if you want to be content, you should own—and want—less Stuff.

Note

Because Stuff has such an important role in your happiness (and unhappiness), it deserves a capital S. You’ll read more about Stuff throughout this book, especially in Chapter 5.

In their personal-finance classic Your Money or Your Life (Penguin, 2008), Joe Dominguez and Vicki Robin argue that the relationship between spending and happiness is non-linear, meaning every dollar you spend brings you a little less happiness than the one before it.

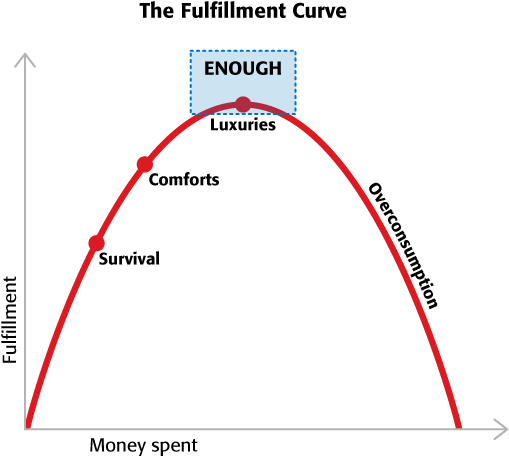

More spending does lead to more fulfillment—up to a point. But spending too much can actually have a negative impact on your quality of life. The authors suggest that personal fulfillment—that is, being content with your life—can be graphed on a curve that looks like this:

This Fulfillment Curve has four sections:

Survival. In this part of the curve, a little money brings a large gain in happiness. If you have nothing, buying things really does contribute to your well-being. You’re much happier when your basic needs—food, clothing, and shelter—are provided for than when they’re not.

Comforts. After the basics are taken care of, you begin to spend on comforts: a chair to sit in, a pillow to sleep on, a second pair of pants. These purchases, too, bring increased fulfillment. They make you happy, but not as happy as the items that satisfied your survival needs. This part of the curve is still positive, but not as steep as the first section.

Luxuries. Eventually your spending extends from comforts to outright luxuries. You move from a small apartment to a home in the suburbs, say, and you have an entire wardrobe of clothing. You drink hot chocolate on winter evenings, sit on a new sofa, and have a library of DVDs. These things are more than comforts—they’re luxuries, and they make you happy. They push you to the peak of the Fulfillment Curve.

Overconsumption. Beyond the peak, Stuff starts to take control of your life. Buying a sofa made you happy, so you buy recliners to match. Your DVD collection grows from 20 titles to 200, and you drink expensive hot chocolate made from Peruvian cocoa beans. Soon your house is so full of Stuff that you have to buy a bigger home—and rent a storage unit. But none of this makes you any happier. In fact, all of your things become a burden. Rather than adding to your fulfillment, buying new Stuff actually detracts from it.

The sweet spot on the Fulfillment Curve is in the Luxuries section, where money gives you the most happiness: You’ve provided for your survival needs, you have some creature comforts, and you even have a few luxuries. Life is grand. Your spending and your happiness are perfectly balanced. You have Enough.

Note

Yup, Enough gets a capital E, too. You’ll learn more about deciding how much is Enough later in this chapter. (And don’t worry: There aren’t any more words with goofy capitals ahead.)

Unfortunately, in real life you don’t have handy visual aids to show the relationship between your spending and your happiness; you have to figure out what Enough is on your own. But as you’ll see in the next section, because we’ve been conditioned to believe that more money brings more happiness, most people reach the peak of the Fulfillment Curve and then keep on spending.

Typically, as your income increases, your lifestyle grows with it. When your boss gives you a raise, you want to reward yourself (you deserve it!), so you spend more. All that new Stuff costs money to buy, store, and maintain. Gradually, your lifestyle becomes more expensive so you have to work harder to earn more. You think that if only you got another raise, then you’d have Enough. But in all likelihood, you’d just repeat the process by spending even more.

Psychologists call this vicious cycle the hedonic treadmill, though you probably know it as the “rat race.” People on the hedonic treadmill think they’d be happy if they just had a little more money. But when they get more money, they discover something else they want. Because they’re never content with what they have, they can never have Enough.

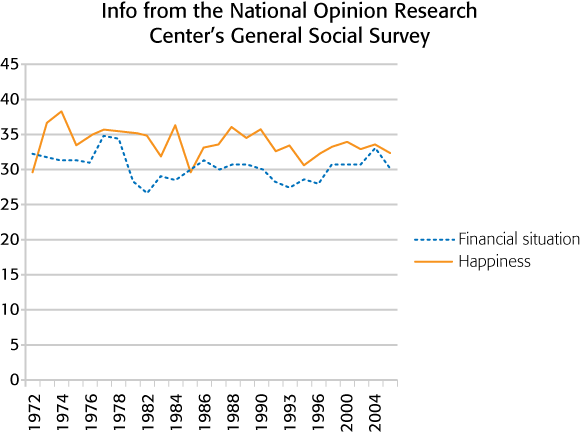

Most Americans are stuck on this treadmill. According to the U.S. Census Bureau (http://tinyurl.com/census-inc), in 1967 the median American household income was $38,771 (adjusted for inflation). Back then, less than one-fifth of U.S. families had color TVs and only one in 25 had cable. Compare that with 2007, when the median household income was $50,233 and nearly everyone had a widescreen color TV and cable. Americans now own twice as many cars as they did in 1967, and we have computers, iPods, and cellphones. Life is good, right? But despite our increased incomes and material wealth, we’re no happier than were in the ’60s.

Note

In case it’s been a while since your last math class, here’s a quick refresher: If you have a set of numbers, half of them will be greater than the median, and half will be less. The median is usually different from the average. For example, in the group of numbers 2, 3, 4, 5, and 101, the average is 23, but the median is only 4. (If economists talked about average incomes instead of median incomes, their numbers would be skewed by billionaires like Warren Buffett.)

Since 1972, the National Opinion Research Center has been polling Americans about their happiness (http://tinyurl.com/norc-gss). As you can see in the following graph, the numbers haven’t changed much over the past 35 years. About one-third of Americans consistently say they’re “very happy” with their lives (http://tinyurl.com/gss-happy), while a little less than one-third say they’re “pretty well satisfied” with their financial situations (http://tinyurl.com/gss-satfin).

If Americans are earning more, why aren’t they happier? We’ve been led to believe that prosperity brings peace of mind, but it turns out your grandfather was right: Money isn’t everything.

The bottom line: Money can’t make you happy if your increased wealth brings increased expectations. In other words, if you want more as you earn more, you’ll never be content; there will always be something else you crave, so you’ll need to work even harder to get the money to buy it. You’ll be stuck on the hedonic treadmill, running like a hamster on a wheel.

The hedonic treadmill leads to lifestyle inflation, which is just as dangerous to your money as economic inflation; both destroy the value of your dollars. Fortunately, you can control lifestyle inflation. You can opt out, step off the treadmill, and escape from the rat race. To do that, you have to set priorities and decide how much is Enough. The next section shows you how.

Kurt Vonnegut used to recount a conversation he had with fellow author Joseph Heller (Vonnegut published this anecdote as a poem in the New Yorker). The two writers were at a party thrown by a billionaire when Vonnegut joked, “How does it feel to know that our host makes more in one day than Catch-22 [Heller’s best-known work] has made in its entire history?” Heller responded, “I’ve got something he can never have. I’ve got Enough.”

Knowing that you have Enough can be better than having billions of dollars. If you’re obscenely rich but aren’t happy, what good is your money? Contentment comes from having Enough—not too little and not too much. But how much is Enough?

There’s no simple answer. What’s Enough for you may not be Enough for your best friend. And what you need to remain at the peak of the Fulfillment Curve (The Fulfillment Curve) will change with time, so Enough is a bit of a moving target. It’s tough to define Enough, but there are some steps you can take to figure out what it means to you.

If you don’t know why you’re earning and spending money, then you can’t say when you have Enough. So take time to really think about what having Enough means to you. Discuss it with your family, and explore the idea with your best friend. Is being debt-free Enough? Being able to pay cash for a new boat? Having a million dollars saved for retirement? Decide what Enough means to you, and then write it down. If you don’t have an end in sight, you’re at greater risk of getting stuck in the rat race.

Note

Personal goals are so critical to financial success that you’ll spend all of Chapter 2 learning how to set them.

Because the notion of Enough is so vague, the best way to approach it is to be mindful of your financial habits. The act of consciously choosing how you spend can help you make purchases that are in line with your goals and values.

Ramit Sethi popularized the concept of conscious spending in his book I Will Teach You to Be Rich (Workman Publishing, 2009). The idea is to spend with intent, deliberately deciding where to direct your money instead of spending impulsively. Sethi argues that it’s okay to spend $5,000 a year on shoes—if that spending is aligned with your goals and values and you’ve made a conscious choice to spend this way (as opposed to spending compulsively—see Curbing Compulsive Spending).

If you’re new to conscious spending, try asking yourself the following questions:

Did I receive value from this equal to the amount I spent? In other words, did you get your money’s worth? You already know that $100 spent on one thing isn’t always as good as $100 spent on another. Conscious spending is about striving to get the most bang for your buck.

Is this spending aligned with my goals and values? Conscious spending means prioritizing: putting your money toward the things you love—and cutting costs mercilessly on the things you don’t. If you’re happy with the coffee at the office, then don’t waste your money at Starbucks. But if your extra-hot nonfat caramel latte is the highlight of your day, then buy the latte! Spend only on the things that matter to you.

The box below tells the story of Chris Guillebeau, who has made a lot of unorthodox choices to be sure his spending matches his priorities.

If you have so much Stuff that you need to rent a storage shed, you have more than Enough. If the Stuff leads to clutter that stresses you out, you’ve passed the peak of the Fulfillment Curve and your added luxuries are bringing you less happiness, not more.

Purging clutter can be a profound experience, but it can be difficult, too: You don’t want to toss anything out because you might need it someday, or it has sentimental value, or it may be worth something.

Getting rid of Stuff only hurts for a little bit. Once you’ve pared your belongings, it’s like a weight has been lifted; you feel free. Some people find the process so liberating that they go farther and practice voluntary simplicity, even to the point of moving into a smaller home. For example, Dave Bruno is chronicling his fight against materialism at his website (http://tinyurl.com/100thingchallenge); his goal is to own only 100 personal items.

A balanced life is a fulfilling life. To find balance, you have to figure out how much is Enough for you—the point where you’re content with what you have and can say “this much, but no more.”

Once you define Enough, you gain a sense of freedom. You’re no longer caught up in the rat race and have time to pursue your passions. You can surround yourself with family and friends, and rediscover the importance of social capital—the value you get from making personal connections with people in your community (see Social Capital). And because you no longer feel compelled to buy more Stuff, you can use your money to save for things that truly matter.

If vast riches won’t bring you peace of mind, what will?

In a 2005 issue of the Review of General Psychology, Sonja Lyubomirsky, Kennon Sheldon, and David Schkade looked at years of research to figure out what contributes to “chronic happiness” (as opposed to temporary happiness). Based on their survey, they came up with a three-part model:

About half of your happiness is biological. Each person seems to have a happiness “set point,” which accounts for roughly 50% of your sense of well-being. Because this set point is genetic, it’s hard to change.

Another 10% of happiness is based on circumstances—external factors beyond your control. These include biological traits like age, race, nationality, and gender, as well as things like marital status, occupational status, job security, and income. Your financial situation is part of this 10%—but only a part—which means it accounts for just a fraction of your total happiness.

The final 40% of happiness comes from intentional activity—the things you choose to do. Whereas circumstances happen to you, intentional activity happens when you act by doing things like exercising, pursuing meaningful goals, or keeping a gratitude journal.

According to the authors, because circumstances—including your financial situation—play such a small role in your general contentment, it makes more sense to boost your bliss through intentional activity, by controlling the things you can and ignoring those you can’t. (You can read the entire article at http://tinyurl.com/hmodel.)

Although your financial situation plays only a small role in your overall happiness, most people believe it’s more important than that. Because of this, many Americans spend their lives striving for more money and possessions—but find that this materialism makes them less happy.

If you’re caught up in the rat race, you may be dealing with things like credit card debt, living paycheck to paycheck, fighting with your spouse over money, and working a job you hate. These problems all stem from one issue: lack of control. When you feel like you have no control over money, you’re worried and stressed. By taking charge of your finances, you can get rid of many of these stressors and be happier. Wealth gives you options and makes it easier to focus on things that can make you content.

This book will teach you specific ways to gain control of your finances. The first step to leading a rich life is learning how to set priorities.

Living richly means figuring out what to spend your time, money, and energy on—and what to ignore. Since you can’t have everything, you have to prioritize. This means spending money on things that matter to you—and skimping on things that don’t.

Psychologists generally agree that a life well-lived is rich in:

Security. It’s hard to be happy when you’re constantly worrying about how to pay the bills. If you have money, you don’t have to worry about those things. (But, as you now know, you don’t have to be rich to be happy.) By living below your means and avoiding debt, you can gain some financial control over your life.

Relationships. True wealth comes from relationships, not from dollars and cents. Wealthy or poor, people with five or more close friends are more apt to describe themselves as happy than those with fewer. A long-term, loving partnership goes hand in hand with this. And as you’ll learn later (Social Capital), social capital can be worth as much as financial capital.

Experiences. As explained in the Note on How Money Affects Happiness, memories tend to grow more positive with time, but Stuff usually drops in value—both actual value and perceived value. As Gregory Karp writes in The 1-2-3 Money Plan (FT Press, 2009), “Experiences appreciate, assets depreciate.” And in Your Money and Your Brain (Simon & Schuster, 2008), Jason Zweig notes, “Doing and being are better than having.”

Remember these three pillars of happiness and you can build a rich life even on a limited income.

To further improve your relationship with money, keep these guidelines in mind:

Prioritize. Spend on the things that make you happiest. There’s nothing wrong with buying things you’ll use and enjoy—that’s the purpose of money. If you’re spending less than you earn, meeting your needs, and saving for the future, you can afford things that make life easier and more enjoyable. (For another way to prioritize, see the box on Living a Rich Life.)

Stay healthy. There’s a strong tie between health and happiness. Anyone who’s experienced a prolonged injury or illness knows just how emotionally—and financially—devastating it can be. Eat right, exercise, and get enough sleep (Your Body: The Missing Manual has loads of tips on how to do all those things).

Don’t compare yourself to others. Financially, psychologically, and socially, keeping up with the Joneses is a trap. You’ll always have friends who are wealthier and more successful in their careers than you. Focus on your own life and goals.

Limit media exposure. Mass media—especially TV—tries to persuade you that happiness depends on things you don’t really need and can’t afford. Studies have found that watching lots of TV can influence your levels of materialism—how much you think you need to be happy.

Simplify. The average Joe believes that materialism is the path to happiness—but the average Joe is wrong. Research shows that materialism actually leads to unhappiness and dissatisfaction. By simplifying your life and reducing the amount of Stuff you own (or want to own), you’ll save money and be happier.

Help others. Altruism is one of the best ways to boost your happiness. It may seem counter-intuitive (and maybe even a little self-serving), but donating to your church or favorite charity is a proven method for brightening your day.

Embrace routine. Emerson wrote, “A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds,” but there’s evidence that some consistency is conducive to contentment. In Happier (McGraw-Hill, 2007), Tal Ben-Shahar recommends building routines around the things you love: reading, walking, gaming, knitting, whatever. Because it can be difficult to make the time for these activities, he argues that we should make rituals out of them. If you enjoy biking, make a ritual out of riding to the park every evening, for example. (See the box below for tips on finding time for what you love.)

Pursue meaningful goals. As you’ll learn in the next chapter, the road to wealth is paved with goals, and the same is true of the road to happiness. But for a goal to be worthwhile, it has to be related to your values and interests—it has to add something to your life. Chapter 2 will help you decide what goals to set.

The bottom line is that if you can’t be content, you’ll never lead a rich life, no matter how much money you have. The key to money management—and happiness—is being satisfied. It’s not how much you have that makes you happy or unhappy, but how much you want. If you want less, you’ll be happy with less. This isn’t a psychological game or New Age mumbo-jumbo, it’s fact: The lower your expectations, the easier they are to fulfill—and the happier you’ll be.

That’s not to say you should lead an aimless life of poverty; quite the opposite, in fact. But most people confuse the means with the ends. They chase after money and Stuff in an attempt to feel fulfilled, but their choices are impulsive and random. Their “retail therapy” doesn’t address the root cause of their unhappiness: They lack goals and an underlying value system to help guide their decisions.

In the next chapter, you’ll learn how to create meaningful financial goals that are aligned with your passions. Then you’ll be able to use these goals to make better decisions about money. These choices will, in turn, help you live a happier life.

Note

For an excellent look at how to be happy, pick up a copy of Gretchen Rubin’s The Happiness Project (Harper, 2009).

Get Your Money: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.