Every Word project you create—whether it’s a personal letter, a TV sitcom script, or a thesis in microbiology—begins and ends the same way. You start by creating a document, and you end by saving your work. Sounds simple, but to manage your Word documents effectively, you need to know these basics and beyond. This chapter shows you all the different ways to create a new Word document—like starting from an existing document or adding text to a predesigned template—and how to choose the best one for your particular project.

You’ll also learn how to work faster and smarter by changing your view of your document. If you want, you can use Word’s Outline view when you’re brainstorming, and then switch to Print view when you’re ready for hard copy. This chapter gets you up and running with these fundamental tools so you can focus on the important stuff—your words.

Tip

If you’ve used Word before, then you’re probably familiar with opening and saving documents. Still, you may want to skim this chapter to catch up on the differences between this version of Word and the ghosts of Word past. You’ll grasp some of the big changes just by examining the figures. For more detail, check out the gray boxes and the notes and tips—like this one!

The first time you launch Word after installation, the program asks you to confirm your name and initials. This isn’t Microsoft’s nefarious plan to pin you down: Word uses this information to identify documents that you create and modify. Word uses your initials to mark your edits when you review and add comments to Word documents that other people send to you (Section 16.3).

You have three primary ways to fire up Word, so use whichever method you find quickest:

Start menu. The Start button in the lower-left corner of your screen gives you access to all programs on your PC—Word included. To start Word, choose Start → All Programs → Microsoft Office → Microsoft Office Word.

Quick Launch toolbar. The Quick Launch toolbar at the bottom of your screen (just to the right of the Start menu) is a great place to start programs you use frequently. Microsoft modestly assumes that you’ll be using Word a lot, so it usually installs the Word icon in the Quick Launch toolbar. To start using Word, just click the W icon, and voilá!

Tip

When you don’t see the Quick Launch toolbar, here’s how to display it: On the bar at the bottom of your screen, right-click an empty spot. From the menu that pops up, choose Toolbars → Quick Launch. When you’re done, icons for some of your programs appear in the bottom bar. A single click fires up the program.

Opening a Word document. Once you’ve created some Word documents, this method is fastest of all, since you don’t have to start Word as a separate step. Just open an existing Word document, and Word starts itself. Try going to Start → My Recent Documents, and then, from the list of files, choose a Word document. You can also double-click the document’s icon on the desktop or wherever it lives on your PC.

Tip

If you need to get familiar with the Start menu, Quick Launch toolbar, and other Windows features, then pick up a copy of Windows XP: The Missing Manual, Second Edition or Windows Vista: The Missing Manual.

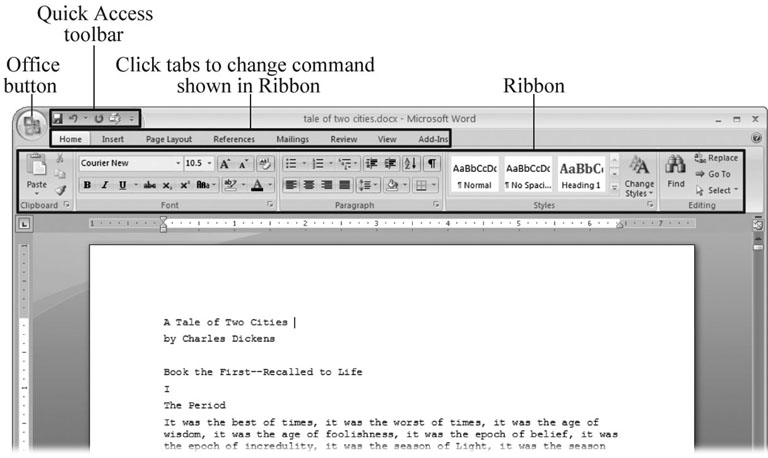

So, what happens once you’ve got Word’s motor running? If you’re a newcomer, you’re probably just staring with curiosity. If you’re familiar with previous versions of Word, though, you may be doing a double take (Figure 1-1). In Word 2007, Microsoft combined all the old menus and toolbars into a new feature called the ribbon. Click one of the tabs above the ribbon, and you see the command buttons change below. The ribbon commands are organized into groups, with the name of each group listed at the bottom. (See Figure 1-1 for more detail on the ribbon.)

When you start Word without opening an existing document, the program gives you an empty one to work in. If you’re eager to put words to page, then type away. Sooner or later, though, you’ll want to start another new document. Word gives you three ways to do so:

Figure 1-1. When you start Word 2007 for the first time, it may look a little top-heavy. The ribbon takes up more real estate than the old menus and toolbars. This change may not matter if you have a nice big monitor. But if you want to reclaim some of that space, you can hide the ribbon by double-clicking the active tab. Later, when you need to see the ribbon commands, just click a tab.

Creating a new blank document. When you’re preparing a simple document—like a two-page essay, a note for the babysitter, or a press release—a plain, unadorned page is fine. Or, when you’re just brainstorming and you’re not sure what you want the final document to look like, you probably want to start with a blank slate or use one of Word’s templates (more on that in a moment) to provide structure for your text.

Creating a document from an existing document. For letters, resumes, and other documents that require more formatting, why reinvent the wheel? You can save time by using an existing document as a starting point (Section 1.2.2). When you have a letter format that you like, you can use it over and over by editing the contents.

Creating a document from a template (Section 1.2.3). Use a template when you need a professional design for a complex document, like a newsletter, a contract, or meeting minutes. Templates are a lot like forms—the margins, formatting, and graphics are already in place. All you do is fill in your text.

Tip

Microsoft provides a mind-boggling number of templates with Word, but they’re not the only source. You can find loads more on the Internet, as described in Section 5.2.1. Your employer may even provide official templates for company documents.

To start your document in any of the above ways, click the Windows logo in the upper-left corner of the screen. That’s Office 2007’s new Office button. Click it, and a drop-down menu opens, revealing commands for creating, opening, and saving documents. Next to these commands, you see a list of your Word documents. This list includes documents that are open, as well as those that you’ve recently opened.

The Office button is also where you go to print and email your documents (Figure 1-2).

Figure 1-2. The phrase most frequently uttered by experienced Word fans the first time they start Word 2007 is, “Okay, where’s my File menu?” Never fear, the equivalent of the File menu is still there—it’s just camouflaged a bit. Clicking the Office button (the one that looks like a Windows logo) reveals the commands you use to create, open, and save Word documents.

Say you want a new blank document, just like the one Word shows you when you start the program. No problem—here are the steps:

Choose Office button → New.

The New Document dialog box appears.

In the upper-left corner of the large “Create a new Word document” panel, click “Blank document” (Figure 1-3).

The New Document box presents a seemingly endless number of options, but don’t panic. The “Blank document” option you want is on the left side of the first line.

At the bottom of the New Document dialog box, click Create.

The dialog box disappears, and you’re gazing at the blank page of a new Word document.

Better get to work.

Figure 1-3. Open the New Document box (Office button → New, or Alt+F, N), and Word gives you several ways to create a new document. Click “Blank document” to open an empty document, similar to the one Word shows when you first start the program. Or you can click “New from existing” to open a document that you previously created under a new name.

A blank Word document is sort of like a shapeless lump of clay. With some work, you can mold it to become just about anything. Often, however, you can save time by opening an existing document that’s similar to the one you want to create. Imagine that you write the minutes for the monthly meetings of the Chief Executive Officer’s Surfing Association (CEOSA). When it’s time to write up the June minutes, it’s a lot faster to open the minutes from May. You keep the boilerplate text and all the formatting, but you delete the text that’s specific to the previous month. Now all you have to do is enter the text for June and save the document with a new name: JuneMinutes.docx.

Note

The .docx extension on the end of the filename is Word 2007’s new version of .doc. The switch from three-letter to four-letter filename extensions indicates a change in the way Word stores documents. (If you need to share documents with folks using earlier versions of Word, choose Office button → Save As → Word 97-2003 document when you save the file. See the box in Section 1.2.3 for details.)

Word gives you a “New from existing” document-creation option to satisfy your desire to spend more time surfing and less time writing meeting minutes. Here’s how to create a new document from an existing document:

Choose Office button → New (Alt+F, N) to open the New Document window. Then click “New from existing…” (it sits directly below the “Blank document” button).

The three dots at the end of the button’s title tell you that there’s another dialog box to come. And sure enough, when you click “New from existing…”, it opens another box, appropriately titled New from Existing Document (Figure 1-4). This box looks—and works—like a standard Windows Open File box. It lets you navigate to a specific folder and open a file.

On your computer, find the existing document you’re using for a model.

You can use the bar on the left to change the folder view. Word starts you in your My Documents folder, but you can switch to your desktop or your My Computer icon by clicking the icons on the left. Double-click folder icons in the large window to open them and see their contents.

Click to select the file, and then click Create New (in the lower-right corner). (Alternatively, just double-click the file’s icon to open it. This trick works in all Open File boxes.)

Instead of the usual Open button at the bottom of the box, the button in the New from Existing Document box reads Create New—your clue that this box behaves differently in one important respect: Instead of opening an existing file, you’re making a copy of an existing file. Once open, the file’s name is something like Document2.docx instead of the original name. This way, when you save the file, you don’t overwrite the original document. (Still, it’s best to save it with a new descriptive name right away.)

Figure 1-4. Use the New from Existing Document box to find an existing Word document that you’d like to open as a model for your new document. When you click Create New at bottom-right, Word opens a new copy of the document, leaving the original untouched. You can modify the copy to your heart’s content and save it under a different file name.

Tip

Windows’ Open File boxes, like New from Existing Document, let you do a lot more than just find files. In fact, they let you do just about anything you can do in Windows Explorer. Using keyboard shortcuts, you can cut (Ctrl+X), copy (Ctrl+C), and paste (Ctrl+V) files. A right-click displays a shortcut menu with even more commands, letting you rename files, view Properties dialog boxes, and much more. You can even drag and drop to move files and folders.

Say you’re creating meeting minutes for the first time. You don’t have an existing document to give you a leg up, but you do want to end up with handsome, properly formatted minutes. Word is at your service—with templates. Microsoft provides dozens upon dozens of prebuilt templates for everything from newsletters to postcards. Remember all the busy stuff in the New Document box in Figure 1-3? About 90 percent of the items in there are templates.

In the previous example, where you use an existing document to create the meeting minutes for the Chief Executive Officer’s Surfing Association (CEOSA), each month you open the minutes from the previous month. You delete the information that pertains to the previous month and enter the current month’s minutes. A template works pretty much the same way, except it’s a generic document, designed to be adaptable to lots of different situations. You just open it and add your text. The structure, formatting, graphics, colors, and other doodads are already in place.

Note

The subject of Word templates is a lengthy one, especially when it comes to creating your own, so there’s a whole chapter devoted to that topic—Chapter 20.

Here’s how to get some help from one of Microsoft’s templates for meeting minutes:

Choose Office button → New (Alt+F, N) to open the New Document window.

On the left of the New Document box is a Template Categories list. The top entry on this list is Installed Templates—the ones Word has installed on your computer.

You could use any of these, but you also have a world of choice waiting for you online. On its Web site, Microsoft offers hundreds of templates for all sorts of documents, and you can access them right from the New Document box. If you have a fast Internet connection, then it’s just as quick and easy to use an online template as it is using the ones stored on your computer. In fact, you’ll use an online template for this example.

Scroll down the Template Categories list to the Microsoft Office Online heading. Under this heading, select Minutes.

In the center pane, you’ll see all different types of minutes templates, from PTA minutes to Annual shareholder’s meeting minutes (Figure 1-5). When you click a template’s icon, a preview appears in the pane on the right.

Figure 1-5. The New Document box lists prebuilt templates that live at Microsoft Office Online in categories like Agendas, Brochures, Calendars, and Minutes. Below the thumbnail you see an estimate of how long it takes to download the template from the Microsoft Office Online Web site. A rating, from 0 to 5 stars, tells you what other people think of the template (the rating system is kind of like the one at Amazon.com).

When you’re done perusing the various styles, click the Formal Meeting Minutes icon. (After all, CEOSA is a very formal organization.) Then click Download.

Word downloads and opens the document.

Start writing up the minutes for the CEO Surfers.

To follow the template’s structure, replace all the words in square brackets ([ ]) with text relevant to CEOSA.

Tip

If you’d rather not download the Formal Meeting Minutes template every time you use it, then you can save the file on your computer as a Word template. The steps for saving files are just around the corner in Section 1.5.

If you’ve mastered creating a document from an existing document and creating a document from a template, you’ll find that opening an existing document is a snap. The steps are nearly identical.

Choose Office button → Open (Alt+F, O). In the Open window (Figure 1-6), navigate to the folder and file you want to open.

The Open window starts out showing your My Documents folder, since that’s where Word suggests you save your files. When your document’s in a more exotic location, click the My Computer icon, and then navigate to the proper folder from there.

With the file selected, click Open in the lower-right corner.

The Open box goes away and your document opens in Word. You’re all set to get to work. Just remember, when you save this document (Alt+F, S or Ctrl+S), you write over the previous file. Essentially, you create a new, improved, and only copy of the file you just opened. If you don’t want to write over the existing document, use the Save As command (Alt+F, A), and then type a new name in the File Name text box.

Figure 1-6. This Open dialog box shows the contents of the tale of two cities folder, according to the “Look in” box at the top. The file tale of two cities. docx is selected, as you can see in the “File name box” at the bottom of the window. By clicking Open, Mr. Dickens is ready to go to work.

Tip

Opening a file in Word doesn’t mean you’re limited to documents created in Word. You can choose documents created in other programs from the Files of Type drop-down menu at the bottom of the Open dialog box. Word then shows you that type of document in the main part of the window. You can open Outlook messages (.msg), Web pages (.htm or .html), or files from other word processors (.rtf, .mcw, .wps).

Now that you know a handful of ways to create and open Word documents, it’s time to take a look around the establishment. You may think a document’s a document—just look at it straight on and get your work done. It’s surprising, though, how changing your view of the page can help you work faster and smarter. When you’re working with a very long document, you can change to Outline view and peruse just your document’s headlines without the paragraph text. In Outline view, you get a better feeling for the manuscript as a whole. Likewise, when you’re working on a document that’s headed for the Web, it makes sense to view the page as it will appear in a browser. Other times, you may want to have two documents open on your screen at once (or on each of your two monitors, you lucky dog), to make it easy to cut and paste text from one to the other.

The key to working with Word’s different view options is to match the view to the job at hand. Once you get used to switching views, you’ll find lots of reasons to change your point of view. Find the tools you need on the View tab (Figure 1-7). To get there, click the View tab (Alt+W) on the ribbon (near the top of Word’s window). The tab divides the view commands into four groups:

Document Views. These commands change the big picture. For the most part, use these when you want to view a document in a dramatically different way: two pages side by side, Outline view, Web layout view, and so on.

Show/Hide. The Show/Hide commands display and conceal Word tools like rulers and gridlines. These tools don’t show when you print your document; they’re just visual aids that help you when you’re working in Word.

Zoom. As you can guess, the Zoom tools let you choose between a close-up and a long shot of your document. Getting in close makes your words easier to read and helps prevent eyestrain. But zooming out makes scrolling faster and helps you keep your eye on the big picture.

Tip

In addition to the Zoom tools on the ribbon, handy Zoom tools are available in the window’s lower-right corner. Check out the + (Zoom In) and–(Zoom Out) buttons and the slider in between them. See Section 1.4.3 for the details on using them.

Window. In the Window group, you’ll find creative ways to organize document windows on your screen—like split views of a single document or side-by-side views of two different documents.

All the commands in the View tab’s four groups are covered in the following pages.

Note

This section provides the short course on viewing your Word documents. For even more details and options for customizing your Word environment, see Chapter 17.

Figure 1-7. The View tab is your document-viewing control center. Look closely, and you see it’s divided into four groups with names at the bottom of the ribbon: Document Views, Show/Hide, Zoom, and Window. To apply a view command, just click the button or label.

Word gives you five basic document views. To select a view, go to the View tab (Alt+W) and choose one of the Document Views on the left side of the ribbon (Figure 1-8). You have another great option for switching from one view to another that’s always available in the lower-right corner of Word’s window. Click one of the five small buttons to the left of the slider to jump between Print Layout, Full Screen Reading, Web Layout, Outline, and Draft views. Each view has a special purpose, and you can modify them even more using the other commands on the View tab.

Figure 1-8. On the left side of the View tab, you find the five basic document views: Print Layout, Full Screen Reading, Web Layout, Outline, and Draft. You can edit your document in any of the views, although they come with different tools for different purposes. For example, Outline view provides a menu that lets you show or hide headings at different outline levels.

Note

Changing your view in no way affects the document itself—you’re just looking at the same document from a different perspective.

Print Layout (Alt+W, P). The most frequently used view in Word, Print Layout, is the one you see when you first start the program or create a new blank document. In this view, the page you see on your computer screen looks much as it does when you print it. This view’s handy for letters, reports, and most documents headed for the printer.

Full Screen Reading (Alt+W, F). If you’d like to get rid of the clutter of menus, ribbons, and all the rest of the word-processing gadgetry, then use Full Screen Reading view. As the name implies, this view’s designed primarily for reading documents. It includes options you don’t find in the other views, like a command that temporarily decreases or increases the text size. In the upper-right corner you see some document-proofing tools (like a text highlighter and an insert comment command), but when you want to change or edit your document, you must first use the View Options → Allow Typing command. For more details on using Word for reviewing and proofing, see Chapter 16.

Web Layout (Alt+W, L). This view shows your document as if it were a single Web page loaded in a browser. You don’t see any page breaks in this view. Along with your text, you see any photos or videos that you’ve placed in the document—just like a Web page. Section 13.2 has more details on creating Web pages with Word.

Outline (Alt+W, U). For lots of writers, an outline is the first step in creating a manuscript. Once they’ve created a framework of chapters and headings, they dive in and fill out the document with text. If you like to work this way, then you’ll love Outline view. It’s easy to jump back and forth between Outline view and Print Layout view or Draft view, so you can bounce back and forth between a macro and a micro view of your epic. (For more details on using Word’s Outline view, see Section 8.1.)

Draft (Alt+W, V). Here’s the no-nonsense, roll-up-your-sleeves view of your work (Figure 1-9). You see most formatting as it appears on the printed page, except for headers and footers. Page breaks are indicated by a thin dotted line. In this view, it’s as if your document is on one single roll of paper that scrolls through your computer screen. This view’s a good choice for longer documents and those moments when you want to focus on the words without being distracted by page breaks and other formatting niceties.

Word gives you some visual aids that make it easier to work with your documents. Tools like rulers and gridlines don’t show up when you print your document, but they help you line up the elements on the page. Use the ruler to set page margins and to create tabs for your documents. Checkboxes on the View tab let you show or hide tools, but some tools aren’t available in all the views, so they’re grayed out. You can’t, for example, display page rulers in Outline or Full Screen Reading views.

Use the checkboxes in the Show/Hide group of the View tab (Figure 1-10) to turn these tools on and off:

Ruler. Use the ruler to adjust margins, set tabs, and position items on your page. For more detail on formatting text and paragraphs, see Chapter 4.

Gridlines. When you click the Gridlines box, it looks like you created your document on a piece of graph paper. This effect isn’t too helpful for an all-text document, but it sure comes in handy if you’re trying to line up photos on a page.

Message Bar. The Message Bar resides directly under the ribbon, and it’s where you see alerts about a document’s behavior. For example, when a document is trying to run a macro and your Word settings prohibit macros, an alert appears in the Message Bar. Click the checkbox to show or hide the Message Bar.

Document Map. If you work with long documents, you’ll like the Document Map. This useful tool appears to the left of your text (you can see it in Figure 1-10), showing the document’s headings at various levels. Click the little + and–buttons next to a heading to expand or collapse the outline. Click a heading, and you jump to that location in your document.

Thumbnails. Select the Thumbnails option, and you see little icons of your document’s pages in the bar on the left. Click a thumbnail to go to that page. In general, thumbnails are more useful for shorter documents and for pages that are visually distinctive. For longer documents, you’ll find the Document Map easier to use for navigation.

When you’re working, do you ever find that you sometimes hold pages at arm’s length to get a complete view, and then, at other times, you stick your nose close to the page to examine the details? Word’s Zoom options (Figure 1-11) let you do the same thing with your screen—but without looking nearly as silly.

Figure 1-10. Use the Show/Hide group on the View tab to display or conceal Word tools. The Ruler gives you a quick and easy way to set tabs and margins. The Document Map is particularly helpful when you work with longer documents because it displays headings in the bar on the left of the screen. In the left pane, you can see that Mr. Dickens wrote more than his fair share of chapters.

Figure 1-11. The Zoom group of options lets you view your document close up or at a distance. The big magnifying glass opens the Zoom dialog box with more controls for fine-tuning your zoom level. For quick changes, click one of the three buttons on the right: One Page, Two Pages, or Page Width.

Note

Even though the text appears to get bigger and smaller when you zoom, you’re not actually changing the document in any way. Zoom is similar to bringing a page closer so you can read the fine print. If you want to actually change the font size, then use the formatting options on the Home tab (Alt+H, FS).

On the View tab, click the big magnifying glass to open the Zoom dialog box (Figure 1-12). Depending on your current Document View (see Section 1.4), you can adjust your view by percentage or relative to the page and text (more on that in a moment). The options change slightly depending on which Document View you’re using. The Page options don’t really apply to Web layouts, so they’re grayed out and inactive if you’re in the Web Layout view.

Figure 1-12. The Zoom dialog box lets you choose from a variety of views. Just click one of the option buttons, and then click OK. The monitor and text sample at the bottom of the Zoom box provide visual clues as you change the settings.

In the box’s upper-left corner, you find controls to zoom in and out of your document by percentage. The view varies depending on your computer screen and settings, but in general, 100% is a respectable, middle-of-the-road view of your document. The higher the percentage, the more zoomed in you are, and the bigger everything looks—vice versa with a lower percentage.

The three radio buttons (200%, 100%, and 75%) give you quick access to some standard settings. For in-between percentages (like 145%), type a number in the box below the buttons, or use the up-down arrows to change the value. For a quick way to zoom in and out without opening a dialog box, use the Zoom slider (Figure 1-13) in the lower-right corner of your window. Drag the slider to the right to zoom in on your document, and drag it to the left to zoom out. The percentage changes as you drag.

Figure 1-13. The Zoom slider at the bottom of the document window gives you a quick and easy way to change your perspective. Drag the slider to the right to zoom in on your document, and drag it to the left to zoom out. To the left of the slider are five View buttons: Print Layout, Full Screen Reading, Web Layout, Outline, and Draft (Section 1.4.2). Since the first button is selected, this document is in Print Layout view.

Not everyone’s a number person. (That’s especially true of writers.) So you may prefer to zoom without worrying about percentage figures. The Zoom dialog box (on the View tab, click the magnifying-glass icon) gives you four radio buttons with plain-English zoom settings:

Page width. Click this button, and the page resizes to fill the screen from one side to the other. It’s the fastest way to zoom to a text size that most people find comfortable to read. (You may have to scroll, though, to read the page from top to bottom.)

Text width. This button zooms in even farther, because it ignores the margins of your page. Use this one if you have a high-resolution monitor (or you’ve misplaced your reading glasses).

Whole page. When you want to see an entire page from top to bottom and left to right, click this button. It’s great for getting an overview of how your headings and paragraphs look on the page.

Many pages. This view is the equivalent of spreading your document out on the floor, and then viewing it from the top of a ladder. You can use it to see how close you are to finishing that five-page paper, or to inspect the layout of a multi-page newsletter.

The ribbon offers radio buttons for three popular page views. (You can see them back in Figure 1-11, to the Zoom tool’s right.) They’re a quick and dirty way to change the number of pages you see onscreen without fiddling with zoom controls.

One Page. This view shows the entire page in Word’s document window. If your screen is large enough, you can read and edit text in this view.

Two Pages. In this view, you see two pages side by side. This view’s handy when you’re working with documents that have two-page spreads, like booklets.

Page Width. This button does the exact same thing as the Page Width button in the Zoom dialog box (Section 1.4.3). It’s more readable than the One Page and Two Page options, because the page fills the screen from edge to edge, making the text appear larger.

Back when dinosaurs roamed the earth and people used typewriters (or very early word processors), you could work on only one document at a time—the one right in front of you. Although Word 2007 has more options for viewing multiple documents and multiple windows than ever, some folks forget to use them. Big mistake. If you ever find yourself comparing two documents or borrowing extensively from some other text, then having two or more documents visible on your screen can double or triple your work speed.

The commands for managing multiple documents, views, and windows are in the View tab’s Window group (Figure 1-14).

Figure 1-14. In the Window group, the three commands on the left—New Window, Arrange All, and Split—let you open and view your work from multiple vantage points. The commands in the middle—View Side by Side, Synchronous Scrolling, and Reset Window Position—are helpful when reviewing and comparing documents. The big Switch Windows button lets you hop from one document to another.

New Window (Alt+W, N). When you’re working on a long document, sometimes you want to see two different parts of the document at the same time, as if they were two separate documents. You may want to keep referring to what you said in the Introduction while you’re working in Chapter 5. Or perhaps you want to keep an Outline view open while editing in Draft view. That’s where the New Window command comes in. When you click this button (or hit this keystroke), you’ve got your document open in two windows that you can scroll independently. Make a change to one window, and it immediately appears in the other.

Arrange All (Alt+W, A). Great—now you’ve got documents open in two or more windows, but it takes a heck of a lot of mousing around and window resizing to get them lined up on your screen at the same time. Click Arrange All and, like magic, your open Word document windows are sharing the screen, making it easy to work on one and then the other. Word takes an egalitarian approach to screen real estate, giving all windows an equal amount of property (Figure 1-15).

Split (Alt+W, S). The Split button divides a single window so you can see two different parts of the same document—particularly handy if you’re copying text from one part of a document to another. The other advantage of the Split command is that it gives you more room to work than using Arrange All for multiple windows because it doesn’t duplicate the ribbon, ruler, and other Word tools (Figure 1-16).

Figure 1-15. One downside of Office 2007’s ribbon: It takes up more space on your computer’s screen than menus or even the older button bars. When you open a couple of windows, you’re not left with much space to do your work, especially when you’re working on an ultra-portable laptop or a computer with a small screen. You can double-click the active tab to hide the ribbon, but in most cases, you’re better off working with a split screen, as shown in Figure 1-16.

Figure 1-16. When you’re viewing two different parts of a single document, use the Split command; it leaves you more room to work than two separate windows, as shown in Figure 1-15. Each section of the split window has a scroll bar, so you can independently control different parts of your document. If you want to fine-tune your split, just drag the middle bar exactly where you want it. When you’re done, click Remove Split to return to a single screen view.

One common reason for wanting to see two documents or more on your screen at once is so you can make line-by-line comparisons. Imagine you have two Word documents that are almost identical, but you have to find the spots where there are differences. A great way to make those differences jump out is to put both versions on your screen side by side and scroll through them. As you scroll, you can see differences in the paragraph lengths and the line lengths. Here are the commands to help you with the process:

View Side by Side (Alt+W, B). Click the View Side by Side command and Word arranges two windows vertically side by side. As you work with side-by-side documents, you can rearrange windows on your screen by dragging the very top of the Window frame. You can resize the windows by pointing to any edge of the frame. When you see a double arrow, just drag to resize the window. Synchronous Scrolling (described next) is automatically turned on.

Synchronous Scrolling (Alt+W, Y). The Synchronous Scrolling feature keeps multiple document windows in lock step. When you scroll one window, the other windows automatically scroll too. Using the same button or keystroke, you can toggle Synchronous Scrolling on and off as you work with your documents.

Reset Windows Position (Alt+W, T). If you’ve moved or resized your document windows as described earlier under View Side by Side, then you can click this button to reset your view so the windows share the screen equally.

From the earliest days of personal computing, the watchword has been “save early, save often.” There’s nothing more frustrating than working half the day and then having the Great American Novel evaporate into the digital ether because your power goes out. So, here are some tips to protect your work from disasters human-made and natural:

Name and save your document shortly after you first create it. You’ll see the steps to do so later in this section.

Get in the habit of doing a quick save with Alt+F, S (think File Save) when you pause to think or get up to go to the kitchen for a snack. (Note for old-timers: Ctrl+S still works for a quick save too.)

If you’re leaving your computer for an extended period of time, save and close your document with Alt+F, C (think File Close).

It’s the Microsoft Way to give you multiple ways to do most everything. Whether that’s because the company’s programmers believe in giving you lots of choices, or because they can’t make up their minds about the best way to do something is a question best left to the philosophers. But the point is, you do have a choice. You don’t have to memorize every keystroke, button, and command. Especially with saving, the important thing is to find a way you like and stick with it. Here’s a list of some ways you can save the document you’re working on:

Ctrl+S. If you’re an old hand at Word, this keyboard shortcut may already be burned in your brain. It still works with Word and other Office programs. This command quickly saves the document and lets you get back to work.

Alt+F, S. This keyboard shortcut does the exact same thing as Ctrl+S. Unlike Ctrl+S, though, you get visual reminders of which keys to press when you press the Alt key. See the box above.

Office button → Save. If you don’t want to use keyboard shortcuts, you can mouse your way to the same place using menus. Like the options above, this command saves your file with its current name.

Office button → Save As. The Save As option lets you save your file with a new name (Figure 1-17). When you use this command, you create a new document with a new name that includes any changes you’ve made. (The individual steps are described in the next section.)

Office button → Close. When you close a document, Word checks to see if you’ve made any changes to the file. When you’ve made changes, Word always asks whether you’d like to save the document (Figure 1-18).

When you save a new document or save a document with a new name (Save As), you’ve got three things to consider: a filename, a file location, and a file format.

Figure 1-19. To open a backup file, choose All Files (*.*) in the “Files of type” drop-down menu at the bottom of the Open dialog box. Look for a file that begins with the words “Backup of.” Double-click to open the file.

Here are the steps for saving a file, complete with a new name:

Choose Office button → Save As to open the Save As box.

You use the Save As command when you’re saving a file with a new name. Word also displays the Save As box the first time you save a new document.

Use the “Save in” drop-down list or double-click to open folders in the window to find a location to store your file.

The buttons in the upper-right corner can also help you navigate. See the details in Figure 1-21. Word doesn’t care where you save your files, so you can choose your desktop or any folder on your computer.

At the bottom of the Save As dialog box, type a name in the File name box.

Word accepts long names, so you don’t need to skimp. Use a descriptive name that will help you identify the file two weeks or two years from now. A good name saves you time in the long run.

Use the “Save as type” box to choose a file type.

In most cases you don’t need to change the file type. Word automatically selects either .docx or .docm depending on the contents of your file, but Word can save files in over a dozen different formats. If you’re sharing the file with someone who’s using an older version of Word, then choose Word 97-2003 Document to save the document in .doc format. If you’re sharing with someone who uses a Mac or Linux computer, then you may want to use the more universal Rich Text Format (.rtf).

Tip

If you want to use your document as a template in the future, then choose Word Template (.dotx). Use the Word Macro-Enabled format (.dotm) if you’ve created any macros (Section 19.2).

Unless you’re sharing your file with someone using an older version of Word or a different operating system or making a template, stick with the new standard Word file types .docx (for normal Word files) and .docm (for files that run macros). See the box in Section 1.2.3 for a complete rundown.

Click Save.

Word does the rest. All you need to do is remember where you saved your work.

Figure 1-21. The Save As dialog box has all the controls you need to navigate to any location on your computer—including five nifty buttons in the upper-right corner. From left to right: The left arrow button steps you backward through your past locations (just like the back button in a Web browser). The up arrow takes you out to the folder enclosing the one you’re in now. The X button deletes folders and files—be careful with it. Click the folder with the star in the corner to create a new folder.

Get Word 2007: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.