Ubuntu, named after a South African word meaning “humanity toward others,” is a free operating system (OS) with a strong focus on usability and ease of installation. It is sponsored by the UK company Canonical Ltd., owned by Mark Shuttleworth.

By keeping Ubuntu free and open source (I’ll define these terms in a moment), Canonical says it is able to utilize the talents of a community of developers. Canonical makes its profit from selling technical support and from creating other services related to Ubuntu.

In 2005 Shuttleworth also created the Ubuntu Foundation, kicking it off with a 10 million dollar grant, which he calls insurance for the project should he ever cease his involvement. The foundation’s purpose is to ensure the support and development for all future versions of Ubuntu. In December 2009, Shuttleworth stepped down as CEO of Canonical to “focus on product design, partnerships, and customers.”

Ubuntu (whose logo you can see in Figure 1-1) strongly relies on other developers, too, as it’s a fork of the Debian project’s code base, itself a popular Linux distribution.

Initially developed in 1993, Debian—a contraction of the first name of the developer, Ian Murdock, along with that of Debra Lynn, a former girlfriend—is not backed by any company, yet it still manages to provide the basis of over a dozen other Linux distributions, and is available as both a desktop and a server operating system.

The Debian project is a volunteer organization with over a 1,000 member developers, each working on different aspects of the OS.

Both Debian and Ubuntu, and most of their constituent parts, are released under the GNU General Public License (GPL) and the Lesser General Public License (LGPL). This is a free software license, meaning that anyone can share the software with other people and any derived works must be available under the same terms.

The term GNU is a recursive acronym (a kind of joke that is popular among software hackers); it stands for GNU’s Not Unix. The GNU project was started in 1984 at MIT by Richard Stallman, who had the goal of making a totally free operating system. This was finally achieved in 1992 with the appearance of the Linux kernel, itself released under the GPL.

The Linux kernel is the core operating system used by all distributions of Linux, and is generally pronounced lin-ucks. It was created in 1991 by Linus Torvalds, a Finnish software engineer, who also had a vision of creating a free operating system.

Because Linux filled a critical gap in the GNU project by providing a working kernel, the total package is often called GNU/Linux. But most people just refer to it as Linux, which I’ll do for the rest of this book.

So far, thousands of programmers have worked on the Linux kernel, with even Microsoft contributing 20,000 lines of code. In fact, so much work has gone into it that in 2006 a European Union study put the redevelopment cost of the kernel at over a billion U.S. dollars.

You may often see a penguin character called Tux used as the Linux logo (see Figure 1-2). It was created by Larry Ewing using GIMP (the GNU Image Manipulation Program) as an entry to a Linux competition. Surprisingly, it didn’t win, but it has since become the official mascot.

Linux comes in a variety of different versions called distributions, or distros for short. Generally each distribution consists of the Linux kernel along with libraries and utilities from the GNU project, as well as a variety of applications such as word processors, spreadsheets, media players, and so on.

Unbelievably, there are estimated to be over 600 distributions of Linux, of which 300 are actively maintained. Of course, the vast majority of them are quite specialized and don’t have many users. However, a significant number of distributions are relatively popular, although none of them comes close to the usage of Ubuntu.

Table 1-1 lists some of the more common distributions, roughly in order of popularity according to the http://distrowatch.com website. Of course there are too many to list them all, so please don’t be disappointed if you don’t see all of your favorites.

Table 1-1. Some of the more popular Linux distributions

Name | Type of distribution |

|---|---|

Ubuntu | A Linux distribution using the GNOME desktop environment |

Fedora | A community distribution sponsored by Red Hat |

Mint | A distribution based on and compatible with Ubuntu |

openSUSE | Originally derived from Slackware and sponsored by Novell |

Debian | A volunteer-driven, noncommercial distribution |

Mandriva | A Red Hat derivative popular in France and Brazil |

PCLinuxOS | A derivative of Mandriva |

Puppy | A very small distribution that fits in 64 MB of memory |

Sabayon | A Gentoo-based distribution |

Arch | An independent distribution targeted at competent Linux users |

CentOS | A 100% compatible rebuild of Red Hat Enterprise Linux |

MEPIS | A Debian-based desktop Linux distribution |

Slackware | One of the first Linux distributions |

Kubuntu | A version of Ubuntu using the KDE desktop environment |

Gentoo | A distribution with FreeBSD similarities, targeted at power users |

Ubuntu Studio | A version of Ubuntu modified for intensive audiovisual work |

Xubuntu | A version of Ubuntu using the Xfce Desktop environment |

Red Hat | A derivative of Fedora maintained by Red Hat |

Edubuntu | A derivative of Ubuntu designed for use in classrooms and schools |

One reason for all these different distributions is that they are usually tailored for specific purposes, such as types of users, ranging from beginner to power user, or for types of computers, ranging from low- to high-end. There are also distributions that focus on education, music, graphics, office, or other tasks.

Some distributions come with the absolute minimum of additional software and a tightly reduced kernel, making them suitable for use in embedded environments such as cell phones or routers, whereas others include every conceivable feature.

Ubuntu treads the middle line. As can be seen from browsing through Table 1-1, there are only a few officially sanctioned versions of Ubuntu, of which the following are covered in this book:

Graphics in Ubuntu are displayed thanks to the X Window System, which is separate from Linux and runs on many other operating systems as well. It’s free and open source, like Ubuntu.

The X Window System was invented in the 1980s at MIT, explaining the terse name. Computer programmers sometimes avoid fanciful labels, to the point where two of the most popular programming languages are named C and R. The X Window System was derived from another one called W, which ran on an operating system from Stanford called V.

Although X has powered the graphics on nearly all Unix systems (and Unix-like systems, including Linux) for over two decades, its development faltered for a while during debates over licensing and leadership. Luckily, a group of dedicated developers reinvigorated the window with the nonprofit X.org, which was responsible for the code on a new, community-centered footing.

In testimony to the importance of healthy community support for free software, X has undergone a pretty thorough rewrite from the ground up and now supports quite a range of sophisticated graphics hardware. It lies at the basis of all the desktops described in the next section.

If you use Windows or a Mac, you will generally access your computer from a graphical desktop environment such as Windows XP, Vista, or 7, or Mac OS X. On Ubuntu Linux, there are three main desktop environments to choose from: GNOME, KDE, and Xfce.

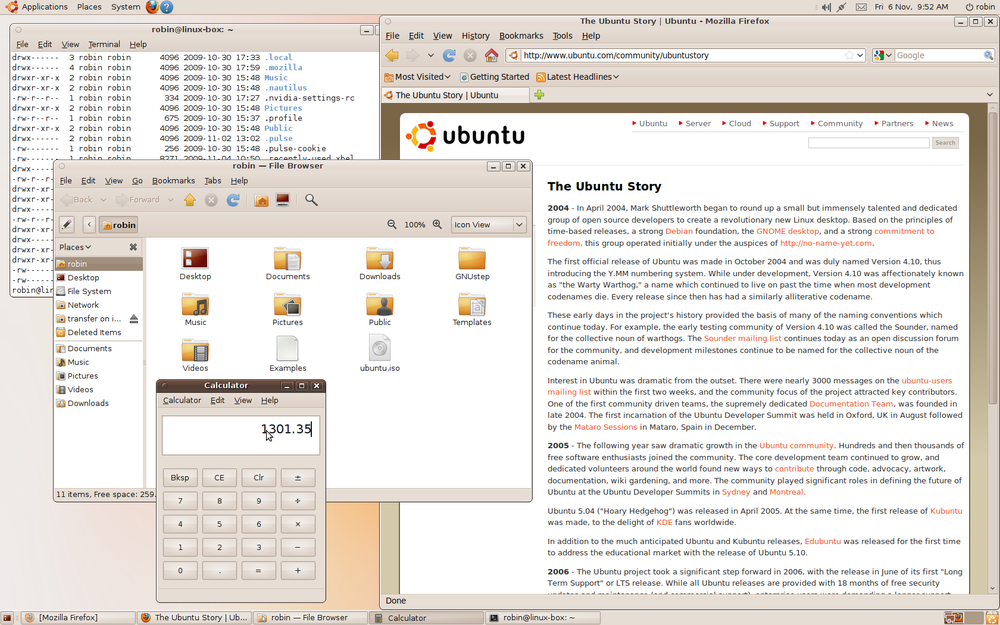

GNOME is the default desktop used by Ubuntu. It was designed to provide a working environment with a heavy emphasis on simplicity, usability, and “making things just work.”

The GNOME project arose because the more popular desktop environment at the time, KDE, was built on a development framework called Qt. At the time, this framework wasn’t licensed under the GPL, and presented potential conflicts of interest.

Therefore, GNOME was built entirely using GPL- and LGPL-licensed software and is an example of many different projects being brought together. Based on the GTK+ toolkit, its look and feel is not too dissimilar from Windows or Mac OS X, with moveable windows that can be resized, a launcher menu, taskbar, and notification area (see Figure 1-3). Other distributions that use GNOME include Debian and Fedora.

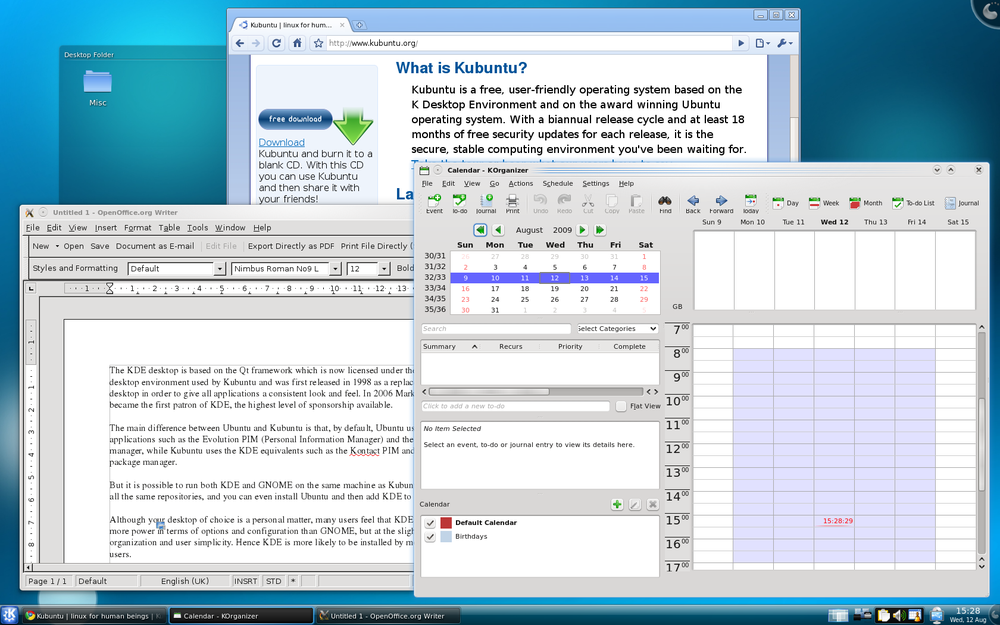

The KDE desktop is based on the Qt framework, which now is licensed under the LGPL. It is the desktop environment used by Kubuntu and was first released in 1998 as a modern Unix desktop that gave all applications a consistent look and feel. In 2006 Mark Shuttleworth became the first patron of KDE, the highest level of sponsorship available.

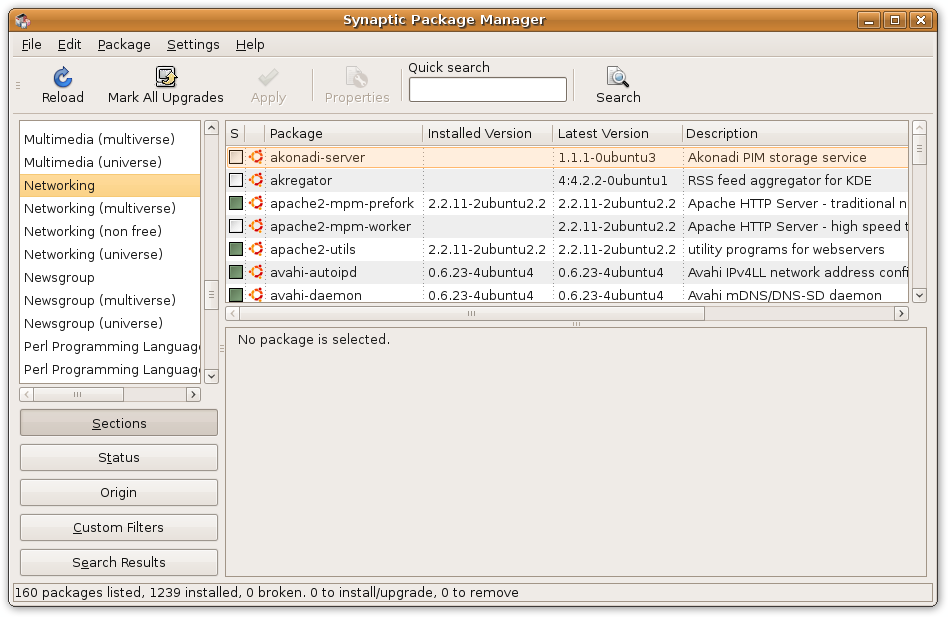

The main difference between Ubuntu and Kubuntu is that, by default, Ubuntu uses GNOME applications, such as the Evolution Personal Information Manager (PIM) and the Synaptic Package Manager, whereas Kubuntu uses the KDE equivalents, such as the Kontact PIM and KPackageKit package manager. There are also numerous programs written for KDE, but you can usually run them from GNOME if you prefer.

However, it is possible to run both KDE and GNOME on the same machine, because Kubuntu and Ubuntu share all the same repositories. You can even install Ubuntu and then add KDE to it, as shown in Figure 1-4. This also has the effect of adding several KDE programs to your GNOME menus, and vice versa.

Although your desktop of choice is a personal matter, many users feel that KDE provides a little more power in terms of options and configuration than GNOME, but at the slight expense of organization and user simplicity. Hence KDE is more likely to be installed by more experienced users. Windows users may also find its “K” menu system, located in the bottom-lefthand corner, reminiscent of the Start Menu.

The Xfce desktop environment is used by Xubuntu Linux (as well as two other Unix-based operating systems: Solaris and BSD) and is based on the same GTK+ toolkit as GNOME, but it uses the Xfwm window manager.

The Xfce philosophy is “small is simple,” as you can see in Figure 1-5. Due to its ability to run on low specification equipment, it is most commonly implemented on systems with old or resource-limited hardware. Its configuration is mouse-driven, with all advanced options hidden from casual users.

Xfce does, however, include an option to preload the libraries for GNOME and KDE, resulting in the ability to mix applications more quickly than the other major desktops. Although it’s extremely fast, some have noted that the Xubuntu desktop is slower than other Xfce implementations.

Xfce is the least used of the three environments, with less than 10% of all Linux desktop installations. That said, it is quite similar to the Windows XP “Classic” desktop and probably deserves more users than it has.

In the same way that KDE is available with Kubuntu, Xfce comes with Xubuntu. But either can be quite easily added to the main Ubuntu distribution, and I’ll show you how to do this in Chapter 2.

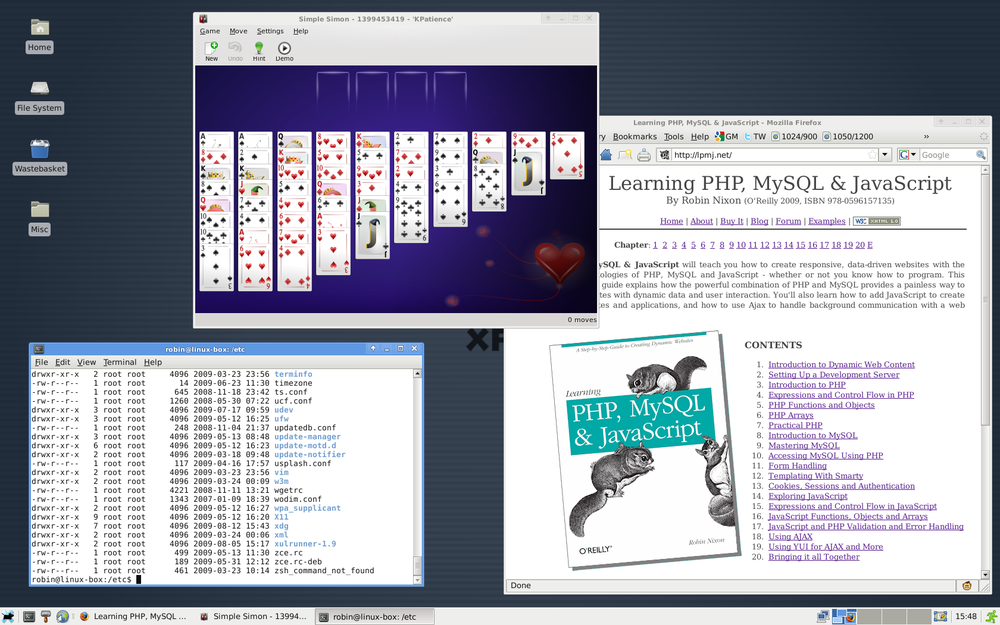

Each distribution is usually split up into smaller packages, some of which become optional add-ons that can be installed using a package manager. There are different managers for different flavors of Linux; Ubuntu uses the Synaptic Package Manager (see Figure 1-6) and, more recently, the Ubuntu Software Center.

If you have heard of people having difficulty installing Linux software, don’t be put off, because package managers have changed all that. You can now install almost any program available for Ubuntu with only a few mouse clicks.

One of the great things about Ubuntu is that it is open source, meaning that not only is it free to use, it’s also free to modify, as long as any modifications you make are released under the same license. This means that the thousands of independent developers working on it have a vested interest in sharing all the latest information with one another. When one developer has a problem, another steps in to help, and vice versa.

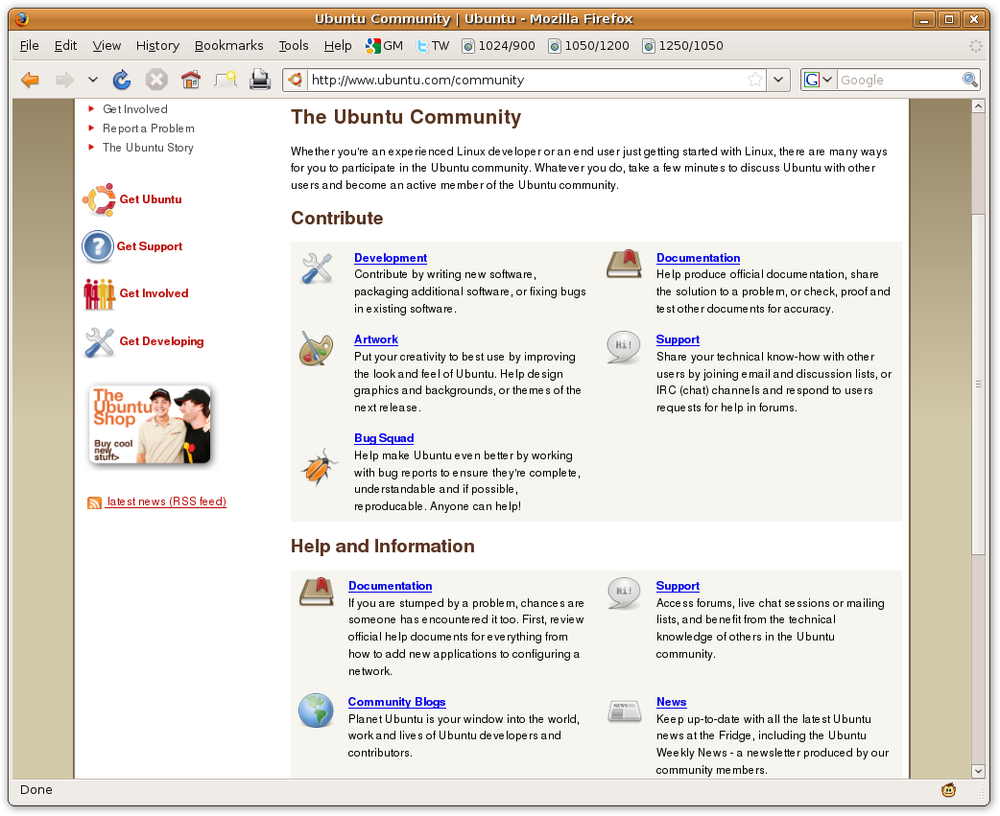

But more than that, there’s a vibrant and growing community that includes Ubuntu’s millions of users. Of course they all communicate with each other via email, instant messages, and list servers, etc., but one of the main meeting points is the Ubuntu Community at http://ubuntu.com/community (see Figure 1-7), where everyone is welcome to join in. Many members also sign the Ubuntu Code of Conduct (http://ubuntu.com/community/conduct), in which they agree to be considerate and respectful of all Ubuntu users and to collaborate with them. So you won’t simply be told to “refer to the documentation” when you ask a question in a forum.

On the website, you’ll find forums covering every aspect of using Ubuntu you can imagine and where, due to its popularity, you can often get an answer to a problem within just a few minutes. There’s also full documentation for all the latest releases, the Planet Ubuntu blog, and The Fridge news website.

You can also get more involved in the community and participate by adding to the program code or documentation, or by contributing artwork, user support, or bug reports. Whatever it is, the Ubuntu Community will welcome you.

There are two releases of Ubuntu each year, generally around April and October. Each release has a major number based on the year and a minor one based on the month. Ubuntu releases are also given code names based on animals, which since the third release have progressed in alphabetical order. A lot of fun precedes each launch, with Ubuntu users everywhere trying to guess whether the next version will be Observant Ostrich or Obvious Otter, and so on. The release history so far is shown in Table 1-2.

Table 1-2. The Ubuntu release history

Version | Code name | Release date | Supported until | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Desktop | Server | |||

4.10 | Warty Warthog | October 2004 | April 2006 | |

5.04 | Hoary Hedgehog | April 2005 | October 2006 | |

5.10 | Breezy Badger | October 2005 | April 2007 | |

6.06 LTS | Dapper Drake | June 2006 | July 2009 | June 2011 |

6.10 | Edgy Eft | October 2006 | April 2008 | |

7.04 | Feisty Fawn | April 2007 | October 2008 | |

7.10 | Gutsy Gibbon | October 2007 | April 2009 | |

8.04 LTS | Hardy Heron | April 2008 | April 2011 | April 2013 |

8.10 | Intrepid Ibex | October 2008 | April 2010 | |

9.04 | Jaunty Jackalope | April 2009 | October 2010 | |

9.10 | Karmic Koala | October 2009 | April 2011 | |

10.04 LTS | Lucid Lynx | April 2010 | April 2013 | April 2015 |

When using Ubuntu, the things you will see on the desktop include applications such as the OpenOffice.org suite of programs (which are compatible with Microsoft Office), the Firefox web browser, or the Terminal (used for entering command-line instructions).

There are also loads of games, graphic manipulation tools, instant messaging utilities, audio-visual applications, and a lot more that I will introduce over the following chapters.

What you won’t see by default in Ubuntu are important operating system files, program source code, configuration files, and the like. Of course, these are all necessary parts of an operating system and are all there, but they are hidden from casual view, unless you know where to look—in which case, you will be more than a casual user.

This means that on the whole you can rummage around and play with what you find in the Ubuntu desktop, update programs, configure peripherals, and so on, all from easy-to-use graphical frontends. This doesn’t mean that you can’t make major changes to your computer, because you can, just as you can with Windows or OS X. But it does mean you won’t need to roll up your sleeves and get under the desktop’s hood too often to configure Ubuntu.

Get Ubuntu: Up and Running now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.