Chapter 1. Hello Twitter

I can remember what life was like without Twitter. The many interesting thoughts popping out of my brain throughout the day had to fight for supremacy. Like an intellectual Thunderdome, only one thought could emerge to become a blog. No one knew when I was sleeping and when I was watching Battlestar Galactica on my TiVo. I had no way of being alerted when someone local was heading to Chicago so that I could express to that person my love of Edwardo’s stuffed pizzas as a passive hint to deliver.

Before Twitter, my connection with the other people in my academic program was constrained by time and space. I could only inquire about their work or ask what they were eating if we were in the same room with overlapping moments of free time. My news about hurricanes and earthquakes was limited to what I could glean from CNN.com and Weather Underground. There were no personal accounts of mass evacuations, nothing to tell me instantly where someone was when the ground started shaking.

Mercifully, a solution emerged. Twitter—a channel for sharing individual status updates with the world—has brought value to the mundane. We have evolved out of that bygone era and into a world measured 140 characters at a time.

Kelly Abbott (@KellyAbbott) of Dandelife introduced me to Twitter through a little Flash widget featured in the sidebar of his blog. It displayed a running list of short journal entries about his life. I clicked and registered my own Twitter account (see Figure 1-1) about a week before the service exploded onto the scene with an award-winning presence at the South by Southwest (SXSW) conference[1] in March 2007.

The estimated number of Twitter accounts surpassed 3 million during the summer of 2008, according to third-party tools. (Twitter does not provide official statistics on membership.[2]) Compete reported an 812% increase in unique monthly visitors to the Twitter website in 2008, jumping to almost 6 million in January 2009.[3] Interest in the channel comes not just from the producers and consumers of content, but also from developers of desktop applications, information visualization systems, Internet mashups, and completely new services not possible before Twitter existed. Tweets—the name given to the brief status updates—are used for many purposes, from alerting local communities about emergency situations to playing games. They can even facilitate the sale of beer. Although Twitter is not without critics, it seems clear that microblogging is here to stay.

You undoubtedly bought or borrowed this book because you are interested in programming some system or widget using the Twitter application programming interface (API). Doing that effectively requires more than just knowing what to code; it is also important to know how your new amazing “thing” is going to fit into the culture Twitter and its users have created. Don’t underestimate the importance of culture. For a thing to be meaningful, it has to have context. In this chapter, we’ll look at the world into which your application will be hatched.

What Are You Doing?

Ian Curry of Frog Design once likened twittering to bumping into someone in a hallway and casually asking, “What’s up?” In a 2007 blog post, Curry noted:

It’s not so important what gets said as that it’s nice to stay in contact with people. These light exchanges typify the kind of communication that arises among people who are saturated with other forms of communication.[4]

Leisa Reichelt of disambiguity called it “ambient intimacy,” the ability to keep in touch with people in a way that time and space normally make impossible.[5] For Wired magazine writer Clive Thompson (@pomeranian99), it’s a “sixth sense,”[6] incredibly useful in understanding when to interact with coworkers. Twitter has also been described as a low-expectation IRC. Brett Weaver considers each tweet the atomic level of social networking.[7] It is a phatic function of communication, keeping the lines of communication between you and someone else open and ready and letting you know when that channel has closed. All of these terms suggest what experience has already taught millions of people: there is great value in small talk.

The main prompt for all this contact on Twitter is a simple question: “What are you doing?” In practice, that question is usually interpreted as, “What interesting thought do you want to share at this moment?” The variety of potential responses is what makes Twitter such a valuable and versatile channel.

The throwaway answers include messages of context, invitation, social statements, inquiries and answers, massively shared experiences, device state updates, news broadcasts, and announcements. Twitter is used for many purposes, including:

Sharing interesting web links

Reporting local news you have witnessed

Rebroadcasting fresh information you have received

Philosophizing

Making brief, directed commentaries to another person

Emoting and venting

Recording behavior, such as a change in location or eating habits

Posing a question

Crowdsourcing

Organizing flash mobs and tweetups (in-person meetups with Twitter friends)

Small comments return big value when shared with the world. Not everyone will read what you post, of course, but those who do get to sample a small bit of your life in a way previously available only to those who happened to bump into you in a hallway or on the street. In this sense, the primary value of Twitter can be found in the small, informal contact it enables between its users.

Twitter is also about emergence. Individual members each compose their own information streams by posting original content and also by reading the updates of other selected members, so the many uses for Twitter can lead to an infinite number of experiences. Each user can tailor her experience to her own wants and needs. However, the sum of all of those unique parts creates new knowledge and inspires useful tools.

Rules of Engagement

While Twitter itself deals with a daily crush of a million or more status updates,[8] the blogosphere is occupying bandwidth talking about Twitter. There are at least 1,500 articles referencing the microblogging channel each day, according to Technorati (see http://technorati.com/chart/Twitter), including 50–350 daily references among the blogs with the highest authority. Many of those posts give advice on how best to use Twitter.

One of the strengths of Twitter is its flexibility. Every information stream is unique and can be customized in the way that best fits the individual at that moment. Are you getting too much information? Unfollow some people. Do you not have time to tweet? Don’t. Want to chat with your two best buds for an hour and chase away all your other followers? Feel free. Because of this versatility, there are no universal rules for how to behave on Twitter; each user can control his own experience.

Here is a sampling of some of the tips and guidelines that have shown up in blogs over the past two years:

Watch your Twitter ratios.

Never follow more than 300 people.

Follow 1 person for every 10 who follow you.

Don’t follow people you’ve never met.

Be active.

Don’t go all mental and tweet four or five times in a row.

Never tweet more than five times a day.

Migrate your real-world conversation to Twitter.

Don’t overdo the

@tweets. It’s a stage whisper.Pre-write some of your material.

Be original and useful.

Don’t try to share your political, religious, or business views in 140 characters.

Don’t post thoughts across multiple tweets.

Don’t put things into Twitter that aren’t designed for Twitter, like photos, audio, etc.

Don’t start posts with “I am.”

Don’t gunk up your stream with machine-readable crapola like “#” or “L:”.

Use contractions whenever possible.

Use numerals, not words, for all numbers.

Provide links and context whenever possible.

Don’t assume other people are having the same experience you are.

Remember that the Twitter question is, “What are you doing?”

Each one of these gems may be considered good advice by some people and horrible advice by others. I have my own set of ever-evolving rules—my twethics—but although you will see some suggestions scattered throughout this book, I won’t lay them all out here, since they apply only to me. You must find your own way, Grasshopper.

Note

Any firm advice on how to use Twitter might undercut one of the dynamics that makes Twitter work: authenticity. It is easy to detect when you treat your relationships with other twitterers as commodities.

Unlike with other channels, each of us has near-complete control over what we see on Twitter. Spammers can only gain a foothold in our tweet streams if we allow their messages in by following them, and we can stop unwanted messages at any point simply by unfollowing the offending users. There are a few basic tells that can help identify a spammer—most notably an insanely unbalanced following-to-follower ratio—but an often-overlooked sign is whether the posts seem authentic. Do the tweets reek of self-promotion? Do they amount to nothing more than an RSS feed? Do you want that?

Everyone has a different experience with Twitter (Figure 1-2[9]). We craft our own experiences when we decide who to follow, what we post, and how we choose to see the results. Ultimately, the burden is on the follower, not the followed, to either communicate dissatisfaction or adjust her stream.

Opportunistic Interruptions

My family used our first tweets to keep in touch with each other over spring break. My wife, Amy, was experiencing Florida with my sons while I was catching up on academic course work and projects. We quickly noticed how much more connected we felt just by reading about little moments that would otherwise have been lost. There are many channels for sharing the bigger things, such as “We’re having another baby” or “I just landed a job writing my first book.” Blogs, letters, phone conversations, family vacations to Grammy’s house—these are all opportunities to share news, but rarely are they used to communicate the smaller experiences that comprise most of our living. Twitter is built for that purpose.

Amy (@amakice) lacked Internet access during that first Twitter vacation, so she posted updates exclusively from her cell phone. This allowed her to share good (and bad) moments on the beach or in the car as they happened. I, on the other hand, was attached to an Internet connection for that first week of Twitter. I started out using the website but quickly realized one of the big limitations—a barrier to use—was that I had to go to Twitter to get my fix. It was somewhat disappointing when I loaded up my profile page and didn’t see a ping from my family.

My appreciation of Twitter changed when I discovered Twitterrific, a third-party desktop client. Twitterrific runs in the background, starting up automatically when I boot up my computer and requiring no action after the initial configuration. It brings my content to me, adding an ambient quality to Twitter. The notifications can be set to appear for short periods of time before going away on their own, which gives me awareness of activity while minimizing the intrusion.

This approach works because most of us only like to be interrupted in a way that is convenient to us. At about the same time Amy was tweeting about building sand castles, University of Illinois researcher Brian Bailey was making the trip to Indiana to talk to our human-computer interaction group about his work. Bailey and others were painstakingly exploring the nature of interruptions by trying to identify the best times to draw attention away from a current task and alert users to new information. This work turned out to be very influential in the way I think about the design of IT, and it is what comes to mind whenever Twitterrific shows me a new tweet from my personal information stream. Installing Twitterrific on my MacBook greatly increased my consumption and enjoyment of Twitter.

Note

Twitterrific got a lot of positive buzz when its manufacturer, Iconfactory, released its iPhone application. For Macintosh desktops, there is a free version and a premium version, where you pay to eliminate the advertising. For other platforms, try Twhirl or Digsby. Another popular desktop application is TweetDeck, which is built on the Adobe AIR platform and adds a way to group the tweets from the people you follow. Tools like these are highly recommended to improve your experience reading tweets.

Twitter works in large part because it fits into one’s own routine. Although many people publish status updates through the main website, the majority of twitterers use third-party publication tools.[10] It is also possible to tweet from a cell phone or via IM. The company maintains a simple API that has spawned hundreds of Twitter applications, giving members even more ways to tell the world what they are doing. Desktop and iPhone clients like Twitterrific and Twhirl enhance the way Twitter works, both as a publisher and as an information conduit.

Note

Twitter disabled its instant message support during the summer of 2008, when the company experienced technical problems trying to handle traffic on its servers. By the fall, Twitter had downgraded the restoration of IM integration to wishful thinking. Third-party developers such as excla.im are trying to pick up the resulting slack to let members once again tweet via IM.

Twitter Is Like a Side-by-Side Conversation

Although the core concept revolves around individual

status updates, there is a communal chat-like quality to Twitter.

Sometimes it’s used for explicit conversations. Tweets can be directed

at specific users with the convention @username, which Twitter interprets as a threaded post. About two in

every five tweets references someone in this fashion, either as a formal

reply—where the @username begins

the tweet—or elsewhere in the content of the tweet. There is a separate

channel just for replies, giving each user the option to include replies

from members not in their usual information stream.

The big problem with this kind of directed conversation is the absence of shared context. When I post “@amakice A frog in a blender” to Twitter, it probably won’t make much sense to anyone who wasn’t following my wife when she tweeted, “What’s green and red?” Since everyone’s information stream is unique, the odds are good that any reply you post is going to be a response to something some of your followers didn’t see. If you aren’t providing enough context to make your tweets accessible to everyone, you are losing people in your audience who realize you aren’t speaking to them.

The perception of personal connection, in spite of the general broadcast of each tweet, led marketer Ed Dale (@Ed_Dale) to dub twittering “side-by-side communication.”[11] A traditional marketing perspective is face-to-face. This suggests combat, as if the business and consumer are assuming martial arts poses. Defenses are raised, and to be received, the message must clear several barriers. Dale’s observation was that Twitter contact is more personal, like two people walking side by side in the same general direction. There is an embedded nonchalance in the way information is exchanged, lowering the barriers to entry on both ends.

That sacred trust can be fleeting. We all have our own thresholds for how much noise or content we can tolerate before taking action in response. That action can materialize as unfollowing the offending person or, more severely, abandoning Twitter altogether. Every tweet, therefore, is as much of a test of your value to others as it is an expression of an idea or desire.

Initially, I vowed to keep my information stream small. I mostly followed people I already knew and avoided anyone using Twitter like a chat client (as in, “@soandso LOL!”). Early in my twittering, my network consisted of four groups of authors: family, colleagues, new acquaintances, and famous people. I thought 50 would be my limit. Two years and several hundred tweeps later, I still feel somewhat conservative in my network management, even if the bars have moved. (You have to follow at least 1,800 others to crack the top 1,000 users, according to third-party Twitter directory TwitDir.)

In 1992, a primate researcher named Robin Dunbar suggested that there is a physical limit, determined by the volume of the neocortex region in the brain, to the number of members in a social group that one person can manage. The Dunbar Number is often reported as 150 people. Some Twitter members follow significantly many more people than that, but the long tail is primarily composed of small balanced networks.[12]

One reason the Dunbar Number likely doesn’t apply to Twitter (or many other social networks) has to do with the same cognitive behavior that allows us to recognize information from a prompt more easily than we can recall it on our own. We rely on external resources, like shopping lists and computer searches, to help us remember things our brains would otherwise forget. Likewise, we can use Twitter to maintain relationships that might otherwise wither, giving us a better chance of renewing them.

Our information streams can grow to include hundreds or thousands of other people because not all of them will be communicating at once. The tweeple we follow will presumably have passed some kind of litmus test to prompt us to follow them in the first place, so the relationships tend to persist.

History of Twitter

One of the best descriptions of Twitter came from Australian web developer Ben Buchanan (@200ok) a few months before the first explosion of new registrations:

It’s faster than email; slower than IRC (in a good way); doesn’t demand immediate attention like IM and has a social/group aspect that SMS alone can’t touch. It is quite odd, but I can’t help thinking this is a sign of things to come. Communications channels that are flexible and quick, personal and tribal...it’s approaching what I imagined when cyberpunk authors talked about personal comm units.[13]

Ben also disclosed his initial reaction to Twitter: “The first time I heard about Twitter I thought it was a stupid idea.” That is an all-too-common refrain from those who haven’t tried the service, or worse, tried Twitter under less than optimal conditions (following too few, tweeting too seldom, relying only on the web interface). Almost as common as that initial “stupid idea” critique is the subsequent change in attitude after giving Twitter a fair shake.

Microblogging, a term for the publication of short messages reporting on the details of one’s life, made the big time in March 2007 when Twitter became the hit of the SXSW conference in Austin. The company set up large screens to display tweets submitted by conference attendees, who signed up for the service in droves. Twitter creator Jack Dorsey (@jack) and early funder Evan Williams (@ev) didn’t invent communication through text, but their company did construct the scaffolding that gave new power to short messages.

Note

In August 1935, Modern Mechanix magazine published an article describing a robot messenger that displayed person-to-person notes. Dubbed “the notificator,” this London-based contraption was like a vending machine for messages. Customers deposited coins to allow their handwritten notes to remain visible in the machine for a few hours. For more information on the notificator, read Dan Hollings’s (@dhollings) 2008 blog post, “Twitter Invented in 1935? Who Would Have Thunk!” (http://danhollings.posterous.com/twitter-invented-in-1935-who-w).

A Brief History of Microblogging

Twitter would not have had the opportunity to befuddle, annoy, and ultimately sway people into daily use without certain technological precursors. Microblogging has its roots in three main technological developments: Instant Relay Chat (IRC), IM chat status messages, and mobile phones.

After a couple decades of computer scientists toying with the idea of distributed chat (see Figure 1-3[14]), IRC came into existence in 1988. Invented by Jarkko Oikarinen, it was the forerunner to instant messaging tools such as Yahoo! Messenger and Google Talk. The IRC community developed a rich language of protocols using special characters to provide instructions from writers to readers.

Two examples of such protocols are the namespace channel (#namespace) and the

directed message (@username). Both

conventions have propagated into current microblogging norms and are

sometimes even hardcoded into the services. Twitter is mulling over the

possibility of officially recognizing the retweet,

which is when a twitterer reposts

a status update first written by someone else. Members establish new

standards by doing things that other people do.

The child of IRC, instant messaging, taught a generation of young Internet users how to chat online with friends in real time. Its popularity grew as it evolved from mere in-the-moment communication into a subculture of creativity expressed via “away” status messages.

In most IM clients, a user can select a custom away message to be displayed when the connection idles or when the user explicitly selects a dormant state. Over time, these messages became more and more creative, moving from a standard “Not at my desk” to more specific explanations of absence, such as “Weeping softly in stairwell A. Back in 10.” This form of cultural communication also crept into social networking sites, most notably Facebook. It became accepted behavior to express oneself in this manner, as did keeping informed about one’s friends by reading their status messages.

The final piece of the puzzle was the mobile phone revolution. This was far more pronounced outside of the U.S., due to late adoption of the technology and a less developed reliance on landline phones. Texting—i.e., sending text messages via the Short Message Service (SMS)—got its start in 1992, when Sema Group’s Neil Papworth sent the first message, from his PC to a friend’s handset: “MERRY CHRISTMAS.” It was 1999, however, before SMS was able to allow communication between providers, which sparked its widespread use. Texting became a legitimate use for a mobile phone and soon became as popular a means of communication as simply talking into the mouthpiece. The maximum length of an 8-bit data message is a familiar 140 characters, which gave rise to the signature constraint of Twitter.

Twitter’s launch showed strong evidence of all three of these cultures—IRC, IM, and SMS—converging at an opportune moment. By that point, people had gotten used to composing short messages on demand. They sought out such messages to understand how the people they cared about were doing. Mobility meant that our spontaneous urges to communicate could be satisfied, and texting allowed us to do so whether or not everyone in our circle had a computer. That was the world into which Jack Dorsey hatched his idea.

Believe It or Not: Twitter Was Inspired by Bike Couriers

“Like most people, it all started with my mother.”

That was how then-CEO Jack Dorsey described the origins of Twitter in a talk he gave in spring 2008.[16] The path he took from that statement to explaining the development of his brainchild was a circuitous one. Try to follow along.

It seems Dorsey’s mom liked to shop for bags, a minor obsession that she passed down to her son. Armed with the knowledge of all things bag, Dorsey’s ideal model was that of the bike courier: a somewhat magical pouch that carries documents, garments, and other packages all over the city. He became fascinated with the flow of physical information that the courier bag facilitates, and he began to think about the digital information used to coordinate all of those activities—coordination known as dispatch. He devoted the early part of his career to programming software in Manhattan at the largest dispatch firm in the world.

Through this job, he noticed patterns emerging. Couriers, taxi drivers, and emergency responders all made status and position reports throughout the day via CB radio. Their messages—such as, “Courier 9 / Empty bag at 5th and 57th,” “Taxi 054 / Passenger dropped off at LGA,” and “Ambulance 12 / Patient having seizure. Going to Bellvue.”—offered brief, specific information about particular individuals. Collectively, though, these messages painted a picture of what was going on in the city at any moment.

Dorsey eventually saw parallels between dispatch messages and IM status messages, except that in the latter case, all the action was tied to the desktop: the status messages reflected work and play taking place at the computer. He also noted that the mobile phone had become one of the things we commonly take with us when we leave the computer. By the time he got to Odeo, a podcasting company then owned by Evan Williams and Biz Stone’s Obvious group, Dorsey was thinking about ways to merge IM status reports and the cell phone’s mobility with dispatch dynamics.

Twitter was built with Ruby on Rails as an internal R&D project, intended to be the thread between devices and social interaction. It was so well received by Odeo employees that Williams decided to release the system—then called twttr—into the wild in July 2006. Robert Scoble (@scobleizer) and other A-list bloggers had already joined by the fall of that year, when it was officially launched, but it wasn’t until Twitter bought a few vowels and won an award at SXSW the following March that the general public started to take notice. Dorsey’s acceptance speech was appropriate to the new medium: “We’d like to thank you in 140 characters or less. And we just did!”

One of the things that made Twitter the darling of the ball was a giant display showing the tweets of those at the conference (Figure 1-4[17]). With this visual ROI for participating, hundreds of new users registered for the service and started texting updates in real time. When the conference attendees left Austin for home and work, they were rabid about sharing their excitement, and the Twitter population exploded.

Twitter dealt with its first known security issue about a month after SXSW: in early April 2007, it was reported that if you knew a Twitter user’s cell phone number, you could spoof that user and access his Twitter timeline.[18] An authentication scheme was quickly added to allow for an optional PIN number to further verify that the SMS originator was the account holder. That same April, Williams spun Twitter off into its own company, naming Dorsey as the CEO, a position he held until Williams assumed the role in October 2008.

Millions and Millions Served

According to TwitDir, a third-party search tool that keeps track of the big nodes in the network, a year after its official launch Twitter boasted about 600,000 public accounts, with over 1,000 new members joining daily. By March 2008—one year after the SXSW award—the number of Twitter accounts had passed the 1 million mark, and two years after its launch there were over 3.5 million registered accounts.[19]

The exact number of Twitter accounts is a closely guarded secret. Bruno Peeters (@BVLG), author of the stats blog Twitter Facts, has paid close attention to the unofficial count provided by TwitDir since April 2007 (Figure 1-5[20]). Aside from a glitch that artificially stalled the count at below 1 million for a couple of months, TwitDir has provided a good estimate of actual Twitter membership figures. TwitDir only accounts for public accounts, however, so the actual figure could be about 10–15% higher when factoring in the private accounts.[21]

Activity on Twitter is exponentially higher than membership. Before most people knew what microblogging was, Twitter recorded its millionth tweet. In September 2008, Nathan Reed’s GigaTweet clock started counting down to the billionth tweet, which arrived in early November 2008.[22] After the milestone was reached, Reed (@reednj) added a few graphs tracking the number of tweets per day.[23] Another monitor is TweetRush, which uses a form of comprehensive use analytics called Rush Hour to look beyond page views and clicks to measure actions and events. According to TweetRush, Twitter gained an additional 150,000 active members and about 1 million tweets each day between November 2008 and January 2009.

Peeters has also spent the past two years tracking the growth of Twitter use by country, everywhere from India to Vatican City. Although the North American market clearly dominates Twitter usage, this may not be the case for long.

Early in 2008, Dorsey and his Twitter pals noticed that 30% of

their traffic originated in Japan. Further investigation showed one of

the reasons: virtual pets. People had begun giving tamagotchi—digital pets that

prompt interaction when they are hungry or lonely or need care—their own

Twitter pages through http://neco.tter.jp

(neco is Japanese for cat). Whenever a member

registered to adopt a new cat, the site created a corresponding Twitter

account to facilitate the interaction. The signature =^..^=, indicating the presence of such an account, began

appearing everywhere. This was one of the things that prompted Twitter

to launch a Japanese version of its service in April 2008. Japanese

quickly became the second most used language on Twitter. The Japanese

version is advertising supported, marking the first monetization of the

service. As of January 2009, unique visitors to the Twitter website

jumped to almost 6 million. A Pew Internet study released at that time

found that 11% of online Americans have used a microblogging or status

update service like Twitter.[24]

Note

The Twitter API is inspiring a wide range of creativity among programmers. Although there is overlap in many of the tools, some developers are creating brand new uses of Twitter beyond simple posting, reading, and following.

The Rise of the Fail Whale

The most recognizable icon for Twitter probably isn’t the bluebird used in its branding. Thanks to numerous server failures at a height of growth in the first half of 2008, the Fail Whale claims that honor. This is the story of the bittersweet success of Twitter’s most notorious cultural footprint.

Because Twitter was initially developed for use by a single, small company, its rapid growth couldn’t be anticipated. Somewhere around the half-million-member mark, it became clear that a threshold of use was near. Big conferences and international events, such as Macworld and the Super Bowl, sparked surges of activity that brought Twitter’s servers to their electronic knees. Initially, members visiting the website were greeted by an image from lolcats of a kitten appearing to work on a computer (Figure 1-6). Eventually, that was replaced with a stock image of a whale being lifted out of the sea by a flock of birds (Figure 1-7). That image became beloved as much as despised, which came in handy late in spring 2008.

By the time Twitter celebrated its millionth member, it was clear that the server architecture had to be improved. A return to SXSW in March was a success, but the added interest increased the burden on the servers. In April 2008, vice president Lee Mighdoll (@mighdoll) and chief architect Blaine Cook (@blaine) left Twitter following another surge in registrations and a period plagued by server downtime and account spamming. This marked the height of a stressful period for the engineers and members of the community alike, as sightings of the Whale were so frequent that the beast became a cultural icon of failure.

Twitter asked users for patience and took measures to stabilize the service. The API rate limit, first invoked six months earlier to battle rogue third-party applications and give the servers some relief, was dropped to a mere 30 requests per hour. Some third-party projects suffered, as they were now unable to ping Twitter for data frequently enough to be effective. The company also disabled some popular features, such as IM support and keyword tracking, to chase away some members. Demand for Twitter was increasing, but experiences were often subpar, with several power users calling for boycotts and migrating to a perceived rival, FriendFeed. Other competitors, such as Plurk and Identi.ca, were able to gain some traction while Twitter struggled. Many compared Twitter to Friendster, which had been a pioneer of online social networking but was long since surpassed by more successful latecomers.

By May, Twitter had started blacklisting spammers, who created accounts and followed members in bulk. The company also emphasized transparency. Engineer Alex Payne (@al3x) began using Google Code’s issue tracker to keep a running tab on issues with the API and the company’s progress in fixing them. Twitter embraced Get Satisfaction, a community source help desk where questions and complaints are addressed in an open forum. It also released a status blog, not served on company machines, to give members information when problems surfaced or solutions were found. The team also added more help, including skilled system administrators Rudy Winnacker (@ronpepsi) and John Adams (@netik), to work on overhauling the old architecture, which was not meant for millions of users and a daily barrage of a million messages.

These proactive efforts started paying off by midsummer. The first major test was the Steve Jobs keynote address at Macworld announcing the iPhone 3G and a suite of applications, as it was sure to generate high traffic on Twitter. The servers survived. Although downtime continued to be problematic throughout June, by the end of July the Fail Whale sightings were no longer a common topic mentioned in tweets.

According to Pingdom, Twitter servers were down the equivalent of almost a full day in May and about half a day in June and July. The site was down for about three days combined in all of 2008. The last major incident came in late July. Since then, however, downtime has been measured in minutes instead of hours, with many days passing without any problems. Even a scheduled maintenance job on October 7 took less than 30 minutes to complete. While serving approximately 3 million more users, Twitter managed to double its response time. By the summer’s end, the company had raised the API rate limit to 100 hits per hour.

Note

Alex Payne isn’t alone in providing support for developers using the API. The team includes Matt Sanford (@mzsanford), who came to Twitter from Summize and is largely responsible for Search API issues, and Doug Williams (@dougw), who was hired in March 2009 to outreach to developers through the @twitterapi account. Doug is also responsible for whitelisting, source requests, and maintaining the API wiki.

Sarah Perez (@sarahintampa) of Read/Write/Web credits Nick Quarantino with giving the signature image the name “Fail Whale,”[25] but blogger Benedikt Koehler tracked down the digital footprint[26] to a video interview Robert Scoble did with Evan Williams at Twitter headquarters, who revealed the name that employees had given the image at just past 24 minutes into the interview.

The designer of that famous image, Chinese artist Yiying Lu (@yiyinglu) of Australia, became known only after a Fail Whale fan tracked her down for permission to make T-shirts. Tom Limongello, whose homemade Fail Whale shirt was a hit at a tech party, approached Yiying and urged her to sell her work online through Zazzle, an on-demand retail shopping website. Sean O’Steen started the Fail Whale Fan Club and maintains the Twitter profile for the cetacean. As a show of support, the group of raised almost $400 to buy shirts for the beleaguered Twitter employees, which they sent in late June at the height of the server issues. That gesture prompted Evan Williams to tweet a response of “Mixed feelings,” along with a link to the web store.

The Fail Whale Fan Club (FWFC) is the most visible representation of the mixed feelings many Twitter members feel when seeing the beast. On the one hand, it is a sign that tweets aren’t flying through cyberspace the way they usually do. On the other hand, the Fail Whale seems to engender more of a sense of shared community experience than the lolcats did. The Fan Club emphasizes this point on its website:

This site is here to poke fun at the people who seem to take online social network downtime a little too seriously. Failwhale.com is not affiliated with Twitter. Rather, it’s a love letter to the hard working folks at all of our favorite online social networking sites who lose sleep over the concept of scalability.

With whale sightings growing less frequent in 2008, the FWFC directed its energies to other endeavors, such as sponsoring parties and promoting a Fail Whale Pale Ale label design contest.

Use of the icon has extended beyond Twitter to other systems. Mashable held a contest in July 2008 challenging readers to come up with a suitable Fail Whale version for Facebook downtime.[27] Responses included an image of birds carrying Facebook creator Mark Zuckerberg, a Fail Snail, and the comment, “A picture of me actually working.” The “failPhone” image surfaced with a 3G in place of the beluga following Apple’s activation nightmare, which bricked many phones. There are even reports of Fail Whale tattoos.[28] Yiyung Lu has kept the spirit of the Fail Whale alive with active use of her own Twitter account and by making appearances at Fail Whale events. She won a Shorty Award for Design, an awards ceremony held on February 11, 2009 in New York City featuring active celebrity twitterers such as Rick Sanchez (@ricksanchezcnn), Shaquille O’Neal (@THE_REAL_SHAQ), and MC Hammer (@MCHammer).[29]

On October 7, 2008, during a scheduled maintenance break, Twitter members saw a completely new image featuring a caterpillar and an ice cream cone. It was the signature of scheduled downtime, not the unintended variety. Twitter has since survived the election of Barack Obama (@BarackObama), New Year’s Eve, a major plane crash, and several technology conferences, all while experiencing record growth and traffic. In an ideal world for Twitter engineers, the Fail Whale will never be seen again.

Who Wants to Be a Millionaire? Gauging Twitter’s Profitability

Fred Wilson (@fredwilson), a venture capitalist and the principal of Union Square Ventures, who invested in Twitter in 2007, has watched the speculation among members of the community and tech business experts about how Twitter is going to make money. In a January 2008 blog response to the ongoing conversation, Fred observed:

Every ounce of time, energy, money, and brainpower you spend on thinking about how to monetize will take you away from the goal of getting to scale. Because if you don’t get to scale, you don’t have a business anyway.[30]

Twitter’s time of reckoning is expected to arrive in 2009, as the company shifts its focus from server stability to accounting stability. It recently cut SMS service in some countries (not the U.S.) after negotiations with local providers stalled. Although some commentators overreacted to the impact this would have on use of the service, the perception was that the move was a sign that the microblogging giant had begun counting pennies. Naturally, the focus of criticism once again turned to whether and how Twitter could make money to keep afloat.

Note

In a March 1, 2009 article on Read/Write/Web, Todd Dagres of Spark Capital—one of the biggest shareholders on Twitter—claimed that Twitter has known its business model for a long time: “All of a sudden there will be some changes that won’t undermine the experience or vitality—but it will be pretty obvious how we’re going to monetize it.”[31]

In an article for Business Week, writer Ben Kunz calculated the worth of each Twitter user at $12.26[32] (the math assumed only traditional forms of Internet advertising, such as banner ads and subscription services). For Twitter or any open service to become profitable, he argued, it needs a balance between opportunities to charge and respect for the dynamics that created the community in the first place. Successful monetization may require some nontraditional thinking that enables the service to remain free to most and allows API development to continue.

Charging for service

During the ongoing conversation about Twitter’s possible monetization strategy, Internet marketer Samir Balwani noted problems with one common suggestion: the “freemium” option.[33] This approach would constrain use of the service by capping the size of the follower network and the number of tweets a user could send over a specified time period. It might also inject advertisements into the information stream until users paid to get rid of them. The primary trouble with this option, according to Balwani, is that it would penalize the most popular and active users, the core members who drive the community; alienating them could kill Twitter. Forcing members to pay could also cause them to migrate to Plurk, Identi.ca, or any other free service.

Balwani also noted that the existence of the API could pose problems for monetization plans. Since most users don’t go to the Twitter website to use the service, it could be difficult to rely on selling ads there. On the other hand, the API would be a boon if Twitter looks to request-rate surcharges as a source of income. The API could be free for projects with a low request rate—continuing to make it possible for developers to create new visualizations and tools—whereas projects that require a higher request rate or need deeper results returned could be forced to pay.

Self-selecting advertisers

Another money-making possibility that would fit the Twitter culture is opt-in advertising. The company could create fee-paying corporate accounts, and then require that all users select at least three of those to follow. Member accounts not actively subscribed to three or more corporate user accounts could be disabled. Perhaps, as with Twitterrific, Twitter could create a second profit point by offering paid memberships that reduce or eliminate the number of corporate accounts a user needs to follow in order to keep his Twitter account active.

This opt-in strategy might prove effective for two reasons. First, if enough advertisers across enough verticals (technology, politics, family, entertainment, religion, etc.) got on board, a real choice would be available to each member. Don’t want to be subjected to Microsoft tweets? Follow Apple. No to Coke? Follow Pepsi. Because the requirement would be modest, a large number of options would make it more likely that the corporate messages would be well received. Second, because the ads would appear in the form of tweets, the advertisers would themselves be members, so the usual follower dynamics would apply to them. Companies that spam or post irrelevant content would be unfollowed and replaced with different advertisers. The beauty of the Twitter channel is that everyone has her own way of using the service and her own tolerance for certain kinds of behavior. This is Ed Dale’s idea of side-by-side marketing at work.

Twitter’s Biz Stone created a minor stir in early 2009 with some comments that suggested the company planned to charge for corporate accounts.[34] The comments were taken by many to mean that Twitter had found its business model, a rumor Twitter had to dispel a few days later.

Implementing an open source service model

Brad Wheeler, chief information officer at Indiana University, evangelizes that companies can make their open source products profitable by focusing monetization on support services. Perhaps the solution for Twitter is not to worry about advertising or membership costs at all, but instead to look at ways of helping individuals trick out and manage their accounts, or to provide development services to companies wishing to leverage the API. The more tweets that pass through the public stream, the easier it is to find people who need help.

Many expected Google to challenge Twitter in 2009 when its 2007 purchase of rival microblogging service Jaiku finally bore fruit, as other such purchases in the past have taken about 18 months to become fully integrated with the search giant. That won’t happen, though. In January 2009, Google announced it was releasing Jaiku to open source and discontinuing Dodgeball, a location-based mobile social networking service. Other threats to Twitter’s microblogging space may come from FriendFeed, Plurk, or Identi.ca, which received some funding in early 2009. However, Twitter is currently a whole power ahead of them in terms of traffic and membership. In 2008 Twitter was valued at about $80 million, having raised $15 million during the summer of that year and an unsolicited $35 million more in February 2009.[35]

Developers Are Users, Too

Alexa.com rankings are only as good as the websites they track. Twitter’s API—released in early 2006 with four simple functions—is responsible for a large percentage of server traffic. The community of developers for Twitter has been busy.

Two key design strategies were instrumental to Twitter’s success.

The first was its simplicity. Unlike some of its microblogging rivals,

Twitter doesn’t try to be more than it is. Members compose short

messages, and Twitter makes sure they are distributed in a

self-organizing network. Requests for longer posts, file sharing,

threaded commentary, group management, and metadata would make Twitter

more complicated than it is now, raising the bar for current and

prospective users. Exceptions can be made, however. For example, so many

twitterers were using the IRC convention for individual replies that the

service added support for the @

command, attaching those tweets to specific user content. With the

increased use of microblogging for monitoring the stock market, the

$company convention is joining

@username,

#hashtag, and RT

(retweet) as part of the operating language of Twitter.

The second key strategy was an enterprise decision: making access to the membership and content mechanisms available to developers. It is getting more and more common for new systems to provide API methods to allow third-party applications to exchange information. Development from the API not only extends the functionality of Twitter, but also creates a personal investment for the programmers in making Twitter successful. Each new application gathers its own following, expanding the use of the service to a wider audience. Most of the cool Twitter innovations—such as that popular Macintosh desktop client, Twitterrific—have not been applications built by the company. There is no need for Twitter to focus on building new tools and features when so many members are sufficiently enamored with the service to want to make it better themselves.

Developers often answer calls for added features by accessing the

API in interesting ways. Jaiku, for example, supports channels—a way of

defining content around topics rather than individuals—whereas Twitter

does not. Nonetheless, developers using Twitter’s API have come to the

rescue by leveraging traditional IRC conventions in their projects.

Hashtags, created by prefixing a keyword with a hash symbol

(#hashtag), provide a means for topic

tracking and are used often enough that Twitter’s own search tool supports them. A

number of third-party clients implement similar functionality, either by

leveraging Twitter’s search API or by following a Twitter account (such

as @hashtags) that monitors the tweets of its

following to form its own database of topical content.

In spring 2008, a third-party company named Summize started tracking the public timeline of Twitter, gathering content to make the tweet corpus searchable. It was widely successful, often up and useful even when Twitter was down. Summize also offered its own API, which spawned a few interesting applications that focused on the content of what was being said rather than on how the networks or streams were constructed. The Twitter team was impressed; it worked with Summize to cover the iPhone application announcements in June and moved to acquire the company in mid-July. The http://search.twitter.com subdomain was created to incorporate Summize technology, and most Summize employees went to work for Twitter.

With the integration of Summize, Twitter now allows content to be searched by specific hashtags.

Note

One of the bigger projects for Twitter engineers in 2008 was to fully integrate the Summize API with Twitter’s own, as each system used slightly different parameter names and approaches. By mid-2009, the API is expected to be one big happy family.

Since Twitter’s splash at SXSW in 2007, other microblogging services have tried to catch that same lightning in a bottle. During the summer of 2007, Jaiku and Pownce—the latter of which closed up shop in December 2008—were Twitter’s biggest rivals, leading a host of similar systems such as MySay, Hictu, MoodMill, Frazr, IRateMyDay, Emotionr, Wamadu, Zannel, Soup, and PlaceShout. A year later, it was FriendFeed, BrightKite, Identi.ca, Plurk, and Yammer stealing some of the thunder. Yammer took the top prize at the TechCrunch50 conference in September 2008[36] as a business version of Twitter (ironically, a concept similar to Jack Dorsey’s original project). Whenever a new startup company involves an information stream, however, the reviews inevitably compare it to Twitter. What separates Twitter from the crowd is its combination of timing, transparency, and simplicity. Whether or not Twitter manages to survive the test of time, microblogging as a communication channel is here to stay.

Note

The Twitter developer community is filled with generous collaborators willing to share code and feedback. On March 24, 2009, the Twitter Developer Nest (@devnest) gathered 90 coders at a Sun Microsystems facility in London to work on applications together. For more information, visit http://twitterdevelopernest.com/.

Creative Uses of Twitter

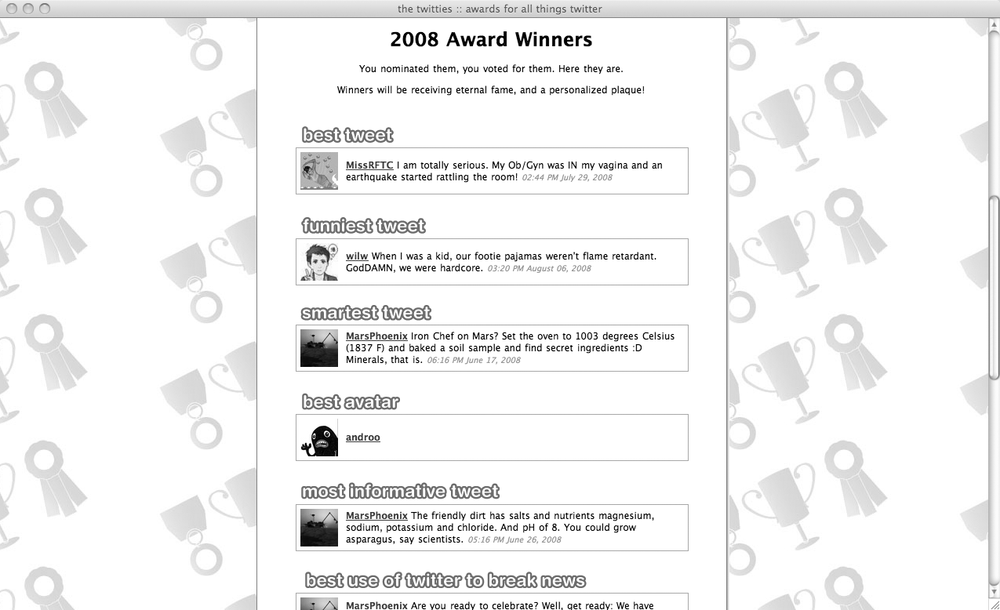

The Academy Awards are great. Each year, about 600 movies are made and about 40 awards are given out (if you count the technical categories). That means there’s a 1 in 15 chance that if you make a movie, you’ll get an Oscar. Those are great odds compared to the pool available for the Twitties, the annual awards for the best tweets in Twitter.

The first annual Twitties, held in 2008, accepted nominations in 14 categories, including Best, Funniest, Smartest, Dopiest, and Snarkiest Tweet (Figure 1-8). If the IDs for Twitter status messages are to be believed, the leading microblogging service generated a nomination pool of almost 870 million tweets in two years. By the time the second annual Twitties rolls around in 2009, there will be over a billion new candidates for the handful of awards.

Collectively, tweets can paint a picture of what a community is thinking and doing. Individually, some status updates stand out. A few of my favorites include:

@hodgman flatbush ave=yet another bklyn street named by random compound word generator.

@brooksguthrie “cakey: Can you build websites with firefox? imarock: can you build cars with roads?”

@noahwesley Our government only breaks international law to take lives, but never to save them.

@katrina_ Sometimes, twitter is that friend you turn to in class when everyone’s being a moron, just to say, “really? Really?!”

@ankitkhare What do you mean, my birth certificate expired?

@jennepenne i think that from now on, when i get cold calls from random marketing people, i will just act like i am drunk.

@fluctifragus The word “webinar” can never be scrubbed from my brain.

People aren’t always this witty, but out of the mass of posts some cleverness arises. The same is true of development projects: not every API application is a winner, but Twitter does inspire some neat tools and toys.

Twitter Utilitarianism

November 2008 marked the second anniversary of Robert Scoble’s first tweet in 2006. At a clip of about 17 tweets a day, this A-list blogger has spent the past two years using Twitter to promote his site and share his life with a mass of readers. Amazingly, Scoble manages to converse with many of his 37,000 followers (most of whom began following him in the past six months). In fact, most of his posts are now directed replies to other users.

Scoble is one extreme on the user spectrum, but he isn’t the leader in any category. According to TwitDir, as of November 2008 the Twitter account for Station Portal (@InternetRadio) held the record as the biggest producer of content, with over 550,000 tweets and counting. Station Portal monitors about 20,000 Internet radio stations, tracking the number of times each song is played. That account is in the top 1,000 with 1,700 followers, but many Twitter accounts that update über-frequently attract very few followers. In the summer of 2008, the twitterer who attracted the most followers was Barack Obama, whose throng of 107,000 followers outnumbered those of Digg’s cocreator Kevin Rose by 40,000—the equivalent of one Scoble. Obama posted about once every three days throughout the campaign.

Note

Most people have balanced networks, which means they follow roughly as many people as they have followers. Imbalances occur mostly with news providers, like @cnn, or with spammers, who follow many people who do not reciprocate.

A University of Maryland study published in 2007[37] captured 1,348,543 tweets from 76,177 members over a two-month period between April and May. The researchers analyzed both the content and the network structure of their sample. One of the outcomes was a graph showing the relationship of tweets to followers, which led them to identify three kinds of Twitter members. Members with high numbers of posts and few followers are considered spammers, and those with many followers and few posts are information sources (e.g., @BarackObama). The authorities—sources such as @Scobleizer and @InternetRadio—have high numbers in both areas.

The same study also concluded that there are four common user intentions for Twitter members:

- Daily chatter

Talk about daily routines and activities

- Conversations

Use of the

@to specifically reference another member- Sharing information

Inclusion of a pointer referenced in the tweet

- Reporting news

Manual and automated reporting of new information, typically through mashups with RSS feeds

This first attempt to officially categorize twitterers through academic analysis offers a good road map for understanding how people make use of their 140 characters to contribute to the information stream. Still, much has changed since the study was done in 2007. The ways people use Twitter today are wide-ranging.

Twitter for News

When Washington state Republican Representative Jennifer Dunn died in September 2007, people read about it on Twitter before the news hit traditional media sources or even Wikipedia. On January 15, 2009, Janis Krums was on a ferry crossing the Hudson River when he snapped a photo of a downed plane and posted it to Twitter with a short message. The photo was picked up by news services. It is easier to compose a sentence or two and share immediately with others than it is to prepare an in-depth report. For bloggers and journalists alike, the tweet stream can be a great source of story ideas.

CNN’s Rick Sanchez, a Hispanic-American news anchor best known for immersive stunts, solicits tweets for his weekly afternoon news show and features them on the air. ReportTwitters, an effort to strengthen the community of professional and amateur reporters, encouraged its members to tweet about the process of getting and filing a story, offering tips and a transparent look behind the bylines.

The pipeline flows the other way, too. News outlets of all sizes, from the BBC and CNN down to local papers and radio stations, make use of Twitter to share breaking news and provide links to their published articles. Bloggers Blog posted information about the 2007–2008 writers’ strike on Twitter, adding to the solidarity base by highlighting the widespread support for the picket line.

Warning

The flip side to news is rumor. As much as we in the Twitosphere like to make a big deal of how quickly we can find out about earthquakes and plane crashes, the desire to keep the information flowing can lead to mistakes. As with any information you find communicated by media, double-check your sources.

Twitter for Science

On May 25, 2008, my wife and I let our two boys stay up late to watch the Phoenix probe land on Mars (televised live on the Science Channel). I remember watching the Space Shuttle Columbia land in the early 1980s—I even took a Polaroid photo of the image on our black-and-white television as it came back to earth, to capture the moment—and I hoped that my sons would remember this in the same way. It probably didn’t take, but NASA gave the mission a permanent record of the approach using a Twitter account written in the “voice” of the probe.

The Phoenix tweeted in the first person throughout the event, including an exciting flurry of posts as the probe approached the designated landing site (“parachute must open next. my signal still getting to Earth which is AWESOME!”). It gave the project personality and attracted over 36,000 followers. NASA used Twitter to break the news that ice had been discovered on Mars, earning one of three Twittie awards for its contribution to the public stream.

Mars Phoenix ended its mission in late 2008, but mission support continues to use the @MarsPhoenix account and leverage the community that formed around the probe. Other NASA Twitter accounts include those for the Mars Rovers, International Space Station, and some shuttle missions.

In February 2009, CNN reported about a Detroit doctor who used Twitter during an operation. Dr. Craig Rogers, the lead surgeon at Henry Ford Hospital, wanted people to know that a tumor can be removed from an organ while leaving the organ intact. As Rogers operated, chief resident Dr. Raj Laungani manned the Twitter timeline. Thiswas the second such in-surgery coverage; Robert Hendrick of https://www.changehealthcare.com had tweeted his own surgery four months earlier while under local anesthesia.[38]

Twitter for God

Westwinds, a church in Michigan, uses multiple Twitter accounts to augment the weekend experience and keep the conversation going throughout the week between services. The integration with offline gatherings began in June 2008 and has attracted 120 followers on Twitter. The tech-savvy church leaders encourage the use of laptops and cell phones to share the religious experience with those not on-site, aggregating a number of accounts into an information stream. They display the feed live on screens during the Sunday services, inviting participants to ask questions or express themselves as the Spirit moves them (Figure 1-9).

Organizer John Voelz (@shameonyoko) is a bit of a technophile who has spent most of the past two decades bringing religious practice into the Age of the Internet. He noted that Westwinds (@westwinds) was reaching thousands more people through its website than the numbers who sat in attendance on any given weekend. He and others added podcasts and streaming video to the toolbox. Twitter was a natural fit for the early adopters in the congregation, as he noted in his blog, Vertizontal:

In my church, I have seen life-altering small groups formed and forged through Twitter. I have seen teams of people mobilized to do volunteer service like nothing else in the past through Twitter. I have seen needs met financially through Twitter. I have made friends through Twitter. I have witnessed theological discussions, seen prayer answered, seen surprise rendezvous’, connected with leaders better, I’ve seen friends come to the aid of others health....[39]

The first Sunday the stream went live, the church buzzed with iPhones, laptops, and 70 people following @westwindsseries on Twitter. A big screen displayed the stream as people entered and continued throughout the service. Many of the posts were light, but some reflected on the service with opinions and affirmations of or struggles with faith (“I have a hard time recognizing God in the middle of everything”). The response was predictable, with some loving the experience and others finding it distracting, but Voelz was buoyed by testimony that Twitter helped people feel part of what was happening and connected to others.

Similarly, the microblogging service Gospelr was created specifically for the Christian community. The purpose of Gospelr, which is integrated with Twitter to keep members from duplicating posts, is to provide a channel for sharing thoughts, prayers, and devotionals.

Twitter for Emergencies

The low barrier to reporting makes Twitter an ideal channel for alerting a community to danger. Rampaging fires in San Diego and earthquakes in California and China were well covered through tweets, providing important information about where the dangers were and what damage had been done, and posting links to deeper resources. The emergency channel extends outside the affected area, giving remote friends and family the opportunity to reach out with thoughts of support and to get confirmation that everything is all right with their loved ones.

Even in my town, when we had our own brush with danger, Twitter beat email and blogs to the punch as a means of alerting the community. Greeting me one morning in October 2007 was the tweet, “A possible sniper on 2nd street? Anybody have details?” This came before an email from our university’s IT director and another from the dean of our school. A full hour after the tweet was sent, our local emergency information system blog posted an entry.

When Hurricane Katrina hit the Gulf Coast, most of the information flowing from the region came not from FEMA or network news, but from the IRC community, who monitored radio communications and transcribed them to a wiki. The Science News Blog sent hurricane information as tweets, and individuals in affected regions—such as children’s storyteller Dianne de Las Casas of Louisiana—tweeted about their evacuation from the area. Reading about strangers’ experiences in such circumstances gives others a way to empathize, a precursor to more active engagement.

Since the Virginia Tech shootings in April 2007, universities have been ramping up their own emergency networks to include multimodal communication, such as text messages and automated phone calls. An article in New Scientist magazine[40] claimed that researchers at the University of Colorado had found that Twitter and other Web 2.0 media channels did a better job of disseminating information than the traditional channels. According to a study conducted by University of Colorado professor Leysia Palen, instead of rumors and gossip, these channels generate “socially produced accuracy.” While traditional media scramble to bring resources to remote locations, social networks benefit from members already situated on-site and preconditioned to share these moments with the world.

At the time of our own “sniper” incident—which turned out to be a frustrated law student using his books for early morning target practice—the number of local twitterers hadn’t achieved a critical mass. Two years later, we have hundreds of people around town ready to tweet.

Twitter for Marketing

From the start, the 140 characters allotted by Twitter have been used effectively to sell books, promote concerts, and interact with fans of television shows. Many blog posts about Twitter seem to be related to leveraging Twitter for marketing. There are many different takes on how this is best done, but most agree that the personal nature of tweet-to-tweet contact makes it a good way to reach consumers and potential business partners without raising their defenses. A recent survey of more than 200 social media leaders revealed that 40% picked Twitter as the top social media service, ahead of LinkedIn and YouTube.[41]

Using Twitter, businesses can announce sales, solicit feedback, and understand customers in a way not really possible through other channels. Because the marketing content is voluntarily included in a personal information stream, it can be highly relevant and tends to be instilled with greater value. Spam is unlikely to become a problem for most users, as the reader must choose to follow the account to get a message. The author must contribute in a way that does not inspire the reader to remove that author’s future content from his stream.

Note

Spam definitely exists on Twitter, but it is largely confined to account spam, or twam. That is, marketers who never intended to use Twitter to connect with others will sometimes create accounts and follow everyone they can from the public timeline. Since notifications of new followers are usually sent by email, this action can bring a lot of eyeballs to a profile link or a simple first tweet.

Twitter took action in the summer of 2008 to improve spam detection and prevention, even hiring a full-time employee to stand watch.

Businesses use Twitter for everything from customer service to creating positive buzz. Greg Yaitanes (@GregYaitanes), director of the new FOX drama Drive, tweeted during the premier party in 2007, providing insights about the people at the party and a behind-the-scenes commentary. (It didn’t help the show, though; FOX canceled Drive not long after the party ended.) Comcast got points for being proactive in responding to complaints posted on Twitter about its cable television and Internet service; Frank Eliason of Philadelphia manages the @Comcastcares account, responding to individuals with troubleshooting suggestions and support information. Many other businesses, from Southwest Airlines (@SouthwestAir) to Whole Foods (@WholeFoods) to Bank of America (@BofA_help), have a Twitter presence to interact with customers and inform them about new products and deals.

Twitter for Social Change

Tweeting isn’t just an opportunity to share experiences and advertise products and services; it is also a means to express political opinions and persuade others to adopt causes. Among the early adopters of Twitter were several politicians, most notably Barack Obama and John Edwards.

In two presidential bids, Edwards proved to be a leader in Web 2.0 politicking. His staff arguably made the best use of Twitter on the campaign trail, with regular updates about his whistle stops and speeches. Although Obama was more successful both online and offline, Edwards created his account four months earlier, posting 87 times and picking up almost 9,000 followers before his concession and the subsequent scandal dropped his count to 6,000. At the time of his election, Obama was managing a mutual network of over 120,000 followers, the largest following in Twitter.

At the start of the election season in 2008, 7 sitting U.S. senators and 32 congressional representatives had active Twitter accounts.[42] By the time President Barack Obama addressed the joint Congress for the first time in February 2009, members of Congress were tweeting during his speech. The presidential debates sparked a lot of involvement by Twitter members as the Twitter website added a special Election stream, filtered to include tweets mentioning the candidates, the campaign, or debates. Current.TV included some of those tweets as part of its live video feed, and Twitter Vote Report used SMS and Twitter to keep track of voter experiences on Election Day. Government participation isn’t limited to the U.S., either: the British Prime Minister and several Canadian politicians also make use of this medium to communicate with constituents.

Note

In mid-2007, Twitter cracked down on “identity squatting” on the names of famous people—especially presidential candidates. As a result, politicians such as Dennis Kucinich had accounts that weren’t in use. This changed once President Obama took office and elected officials started tweeting regularly.

There are other examples of social activism. Live Earth, a 24-hour, 7-continent concert in 2007 to benefit the SOS environmental project, used Twitter to promote its music event across several sites. Each venue showcased the latest energy-efficiency practices and was designed to minimize the environmental impact of the concert. The Sunlight Foundation, whose goal is to create a more transparent Congress, organized a Twitter petition to oppose restrictions preventing elected officials from tweeting in session. They now have their own suite of APIs and are encouraging developers to help make government more transparent.

In February 2009, Guardian writer Paul Smith (@twitchhiker) announced that he planned to “travel by Twitter” in a stunt intending to raise money for charity: water, a project to improve worldwide access to safe, clean drinking water. (This charity was also a main beneficiary of Twestival [http://twestival.com], a global tweetup on February 12, 2009 when twitterers from 202 cities met to raise money—more than $250,000—and awareness for the cause.) Smith’s plan was to start in his hometown of Newcastle upon Tyne in the U.K. and attempt to travel halfway around the world in one month, to an island off the coast of New Zealand. His self-imposed rules included relying only on people who followed his @twitchhiker account and offered travel and lodging through public replies. Smith documented the experience on his blog as well as through Twitter.

Sometimes Twitter activism can be reactionary. Parents on Twitter responded strongly to a new ad campaign for the over-the-counter pain-relief drug Motrin®. The slick-looking ad was very well produced, bringing to mind the great short film Le Grand Content.[43] However, the content was, at best, out of touch with the consumer group its producers meant to persuade. With many retweets and a simple hashtag, word spread quickly, and other media (blogs and video channels) were leveraged to organize opinion against Motrin. By Monday morning, the company had announced it was pulling the ad campaign. Although this incident clearly demonstrates the effectiveness of Twitter as a conduit for activism, some people question whether the response was disproportionate.[44]

Twitter for Money

One forward-thinking early adopter decided to use Twitter to sell books. TwitterLit—and the children’s book version, KidderLit—provides a daily link to purchase a book online through an Amazon affiliate account. To prompt followers to click, Debra Hamel (@Debra_Hamel) posts the first line of a book as a tweet. No author or title is included, which turns the post into a daily guessing game.

Some of the first lines are more recognizable than others:

| “Call me Ishmael.” |

| “In a hole in the ground, there lived a hobbit.” |

| “As Gregor Samsa awoke one morning from uneasy dreams, he found himself transformed into a giant insect.” |

| “It was a dark and stormy night.” |

| “Dorothy lived in the midst of the great Kansas prairies, with Uncle Henry, who was a farmer, and Aunt Em, who was the farmer’s wife.” |

| “I am an invisible man.” |

Financial success is difficult to achieve. Other attempts at affiliate linking might be perceived as spam, but Hamel’s sites have managed to accumulate about 5,000 followers, and she has faithfully posted some 1,400 first-line links. This is a clever and effective use of Twitter for business.

Twitter for Games

Inspired by the 1924 Richard Connell short story “The Most Dangerous Game,” Minnesota resident Aric McKeown (@aric) created a community game of hide-and-seek for the Minneapolis-St. Paul area using a Twitter account. Twice a month, Aric spent a Saturday afternoon in a local coffee shop or business tweeting clues about his location for followers to use to find him and earn a little sponsored prize. Unlike Connell’s story, set on a remote island, Aric’s version of the sport of human hunting was nonlethal—he called it the Least Dangerous Game. Correctly guessing his location wasn’t the goal; rather, the LDG was a multimodal activity where Twitter facilitated a face-to-face meeting. The first follower to find him won a prize and some bandwidth on a weekly podcast.

Following SXSW in 2008, humorist Ze Frank (@zefrank) organized a Twitter Color War. Members were asked to choose a team color and had to work to get the most followers. Icons were changed to flaunt color affiliations, and a leaderboard was set up until the war ended two months later. The idea was based on a game played at summer camps, where campers split up into color teams and compete in events like tug-of-war and egg tossing. Frank adapted the concept for Twitter, urging players to form teams and compete for medals in various contests. The activities included:

Reverse caption, where contestants provide a picture to illustrate a caption

Mixing a nerd rap with the word “bacon” in the lyrics, to be judged

Creating a merit badge with Photoshop

Battle of roshambo (rock-paper-scissors) throw-down photos

A bingo game, with numbers called through tweets

The Broom Game, where contestants spin in circles while holding a broom above their heads

“Young me, Now me,” i.e., recreating childhood pictures

A scavenger hunt using Google Street View to find 31 things

Fifty-four teams earned medals or badges during the color war, which was eventually won by @teampuce.

Note

Twitter games can be a double-edged sword. For all of the community goodwill they generate, they can also create a lot of noise for followers. In effect, each participant becomes two identities: the one you want to follow, and the one playing the game.

Twitter for Anthropomorphism

We have recently entered a new age of Twitter utility. From simple bedroom lights to houseplants to historic bridges, the inanimate world is coming alive in the form of tweets, which both alert and respond to user interactions.

In the U.K., the London Bridge (@towerbridge) alerts its 700 followers when the bridge is going up and down. A schedule is available online, but it isn’t always at the top of a Brit’s mind to check the website. Tom Armitage engineered a way for the bridge to automatically tweet five minutes before it lifts, and again when it closes. The bridge is “friends” with several large telescopes, which similarly tweet whenever they move to observe a different part of the sky.

I’m not clear about the practical applications of being able to use Twitter to turn on and off your lights—beyond being a burglar deterrent or conveniently illuminating the front room as you pull into the driveway—but someone recently figured out how to do it. 2008 was also the year of the twittering plant. Botanicalls.com published a blow-by-blow instruction page explaining how to rig up a houseplant to tweet when it is thirsty (http://www.botanicalls.com/kits/). When a plant on the network needs water, it can call users to ask for a drink and then give thanks when it is shown some love. Five different status updates are available: low moisture, critically low moisture, not enough watering, over watering, and thirst quenched. Perhaps most impressively, at least for home movie buffs, is the RoBe:Do robot that responds to Twitter requests to make and deliver popcorn.[45]

These feats of simple engineering are likely paving the way for more complicated and useful integrations of Twitter in the future.

Twitter for Help

Members have been relying on tweets to answer their simple questions since the inception of the service. It is not uncommon to solicit opinions about restaurants, websites, or movies by posting an inquiry on Twitter. Sometimes the answers can have life-changing implications.

In April 2008, University of California, Berkeley graduate student James Buck (@jamesbuck) and his translator were arrested in Egypt for photographing a protest. Before authorities processed him, Buck used his mobile phone to send a simple status update—“Arrested”—to Twitter. Some of his few dozen followers contacted Berkeley, the press, and the U.S. Embassy in Cairo to get him some help. The detainee continued to update his social circle about his plight until he was released the next day, thanks to the efforts of legal counsel hired by his university. Mohammed Maree, the translator, wasn’t as lucky; he was detained in the Mahalla jail until July 6.

For more basic help, the human-guided search engine ChaCha offers a Twitter-related option. Users can send questions to ChaCha as text messages or over the phone, and a human will do the work and provide answers. ChaCha also established a Twitter account to post short questions and answers to, but the tweets stopped when Twitter dropped IM support.

The best way to find answers on Twitter is simply to ask your social circle. If your friends don’t know, they may retweet the question and find answers from a wider audience. Another option is LazyTweet, a community built around answering questions. By including the #lazytweet hashtag with your question, you automatically post it to a discussion forum, where others outside of your follow network can attempt to answer it for you.

Twitter for Creativity

From Twitter’s start, the 140-character constraint has proved both an incentive and an inspiration for people to compose short, efficient messages. Inspired by Ernest Hemingway’s famous six-word story—“For Sale: Baby shoes, never used.”—one user once offered prizes for the best six-word tweet. More recently, Brian Clark of Copyblogger issued a challenge to write a story in exactly 140 characters (Figure 1-10). If only doctoral dissertations worked that way!

Clark (@copyblogger), whose blog is about effective writing, arranged several sponsorships and drew 331 submissions for his version of the challenge. A panel of five experts gave the first-place booty to Ron Gould (@rgouldtx), whose entry was:

“Time travel works!” the note read. “However you can only travel to the past and one-way.” I recognized my own handwriting and felt a chill.[46]