Chapter 1. What Would You Say You Do Here?

The idea of a staff engineer track, or “technical track”, is new to a lot of companies. Organizations differ on what attributes they expect of their most senior engineers and what kind of work those engineers should do. Although most agree that, as Silvia Botros has written, the top of the technical track is not just “more-senior seniors,” we don’t have a shared understanding of what it is. So we’ll start this chapter by getting existential: why would an organization want very senior engineers to stick around? Then, armed with that understanding, we’ll unpack the role: its technical requirements, its leadership requirements, and what it means to work autonomously.

Staff engineering roles come in a lot of shapes. There are many valid ways to do the job. But some shapes will be a better fit for some situations, and not all organizations will need all kinds of staff engineers. So I’ll talk about how to characterize and describe a staff engineering role: its scope, depth, reporting structure, primary focus, and other attributes. You can use these descriptions to be precise about how you want to work, what kind of role you’re looking to grow into, or who you need to hire. Finally, since different companies have different ideas of what a staff engineer should do, we’ll work on aligning your understanding with that of other key people in your organization.

Let’s start with what this job even is.

What Even Is a Staff Engineer?

If the only career path was to become a manager (like in the company depicted on the left in Figure 1-1), many engineers would be faced with a stark and difficult choice: stay in an engineering role and keep growing in their craft or move to management and grow in their careers instead.

So it’s good that many companies now offer a “technical” or “individual contributor” track, allowing career progression in parallel to manager roles. The ladder on the right in Figure 1-1 shows an example.

Figure 1-1. Two example career ladders, one with multiple paths.

Job ladders vary from company to company, enough that it’s given rise to a website, levels.fyi, that compares technical track ladders across companies.1 The number of rungs on these ladders varies, as do the names of each rung. You may even see the same names in a different order.2 But, very often, the word senior is used. Marco Rogers, a director of engineering who has created career ladders at two companies, has described the senior level as the “anchor” level for a career ladder. As Rogers says, “The levels below are for people to grow their autonomy; the levels above increase impact and responsibility.”

Senior is sometimes seen as the “tenure” level: you don’t need to go further.3 But if you do, you enter the “technical leadership” levels. The first rung above senior is often called “staff engineer,” and that’s the name I’ll use throughout this book.

In the dual-track job ladder from Figure 1-1, a senior engineer can choose to build the skills to get promoted to either a manager or a staff engineer role. Once they’ve been promoted, a role change from staff engineer to manager, or vice versa, would be considered a sideways move, not a further promotion. A senior staff engineer would have the same seniority as a senior manager, a principal engineer would equate to a director, and so on; those levels might continue even higher in the company’s career ladders. (To represent all of the roles above senior, I’m going to use staff+, an expression coined by Will Larson in his book Staff Engineer.)

So that’s what the job looks like on a ladder. But let’s look at why the technical leadership levels exist. I talked in the introduction about the three pillars of the technical track: big-picture thinking, project execution, and leveling up. Why do we need engineers to have those skills? Why do we need staff engineers at all?

Why Do We Need Engineers Who Can See the Big Picture?

Any engineering organization is constantly making decisions: choosing technology, deciding what to build, investing in a system or deprecating it. Some of these decisions have clear owners and predictable consequences. Others are foundational architectural choices that will affect every other system, and no one can claim to know exactly how they’ll play out.

Good decisions need context. Experienced engineers know that the answer to most technology choices is “it depends.” Knowing the pros and cons of a particular technology isn’t enough—you need to know the local details too. What are you trying to do? How much time, money, and patience do you have? What’s your risk tolerance? What does the business need? That’s the context of the decision.

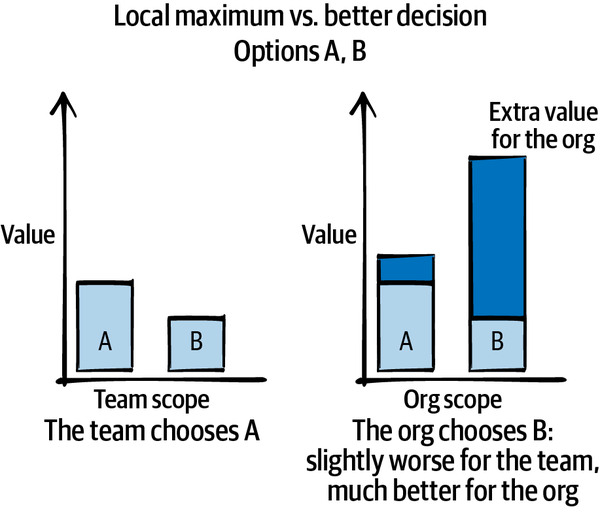

Gathering context takes time and effort. Individual teams tend to optimize for their own interests; an engineer on a single team is likely to be laser-focused on achieving that team’s goals. But often decisions that seem to belong to one team have consequences that extend far beyond that team’s boundaries. The local maximum, the best decision for a single group, might not be anything like the best decision when you take a broader view.

Figure 1-2 shows an example where a team is choosing between two pieces of software, A and B. Both have the necessary features, but A is significantly easier to set up: it just works. B is a little more difficult: it will take a couple of sprints of wrangling to get it working, and nobody’s enthusiastic about waiting that long.

From the team’s point of view, A is a clear winner. Why would they choose anything else? But other teams would much prefer that they choose B. It turns out that A will make ongoing work for the legal and security teams, and its authentication needs mean the IT and platform teams will have to treat it as a special case forever. By choosing A, the local maximum, the team is unknowingly choosing a solution that’s a much bigger time investment for the company overall. B is only slightly worse for the team, but much better overall. Those extra two sprints will pay for themselves within a quarter, but this fact is only obvious when the team has someone who can look through a wider lens.

Figure 1-2. Local maximum versus better decision.

To avoid local maxima, teams need decision makers (or at least decision influencers) who can take an outsider view—who can consider the goals of multiple teams at once and choose a path that’s best for the whole organization or the whole business. Chapter 2 will cover zooming out and looking at the bigger picture.

Just as important as seeing the big picture of the situation now is being able to anticipate how your decisions will play out in future. A year from now, what will you regret? In three years, what will you wish you’d started doing now? To travel in the same direction, groups need to agree on technical strategies: which technologies to invest in, which platforms to standardize on, and so on. These huge decisions can end up being subtle, and they’re often controversial, so essential to making the decision is being able to share context and help others make sense of it. Chapter 3 is all about choosing a direction as a group.

So, if you want to make broad, forward-looking decisions, you need people who can see the big picture. But why can’t that be managers? And why can’t the chief technology officer (CTO) just know all of the “business things,” translate them into technical outcomes, and pass on what matters?

On some teams, they can. For a small team, a manager can often function as the most experienced technologist, owning major decisions and technical direction. In a small company, a CTO can stay deeply involved in the gory details of every decision. These companies probably don’t need staff engineers. But management authority can overshadow technical judgment: reports may feel uncomfortable arguing with a manager’s technical decisions even when there’s a better solution available. And managing other humans is itself a full-time job. Someone who’s investing in being a good people manager will have less time available to stay up to date with technical developments, and anyone who is managing to stay deeply “in the weeds” will be less able to meet the needs of their reports. In the short term that can be OK: some teams don’t need a lot of attention to continue on a successful path. But when there’s tension between the needs of the team and the needs of the technical strategy, a manager has to choose where to focus. Either the team’s members or its technical direction get neglected.

That’s one reason that many organizations create separate paths for technical leadership and people leadership. If you have more than a few engineers, it’s inefficient—not to mention disempowering—if every decision needs to end up on the desk of the CTO or a senior manager. You get better outcomes and designs if experienced engineers have the time to go deep and build the context and the authority to set the right technical direction.

That doesn’t mean engineers set technical direction alone. Managers, as the people responsible for assigning headcount to technical initiatives, need to be part of major technical decisions. I’ll talk about maintaining alignment between engineers and managers later in this chapter, and again when we’re talking strategy in Chapter 3.

Why Do We Need Engineers Who Lead Projects That Cross Multiple Teams?

In an ideal world, the teams in an organization should interlock like jigsaw puzzle pieces, covering all aspects of any project that’s underway. In this same ideal world, though, everyone’s working on a beautiful new green-field project with no prior constraints or legacy systems to work around, and each team is wholly dedicated to that project. Team boundaries are clear and uncontentious. In fact, we’re starting out with what the Thoughtworks tech consultants have dubbed an Inverse Conway Maneuver: a set of teams that correspond exactly with the components of the desired architecture. The difficult parts of this utopian project are difficult only because they involve deep, fascinating research and invention, and their owners are eager for the technical challenge and professional glory of solving them.

I want to work on that project, don’t you? Unfortunately, reality is somewhat different. It’s almost certain that the teams involved in any cross-team project already existed before the project was conceived and are working on other things, maybe even things that they consider more important. They’ll discover unexpected dependencies midway through the project. Their team boundaries have overlaps and gaps that leak into the architecture. And the murky and difficult parts of the project are not fascinating algorithmic research problems: they involve spelunking through legacy code, negotiating with busy teams that don’t want to change anything, and divining the intentions of engineers who left years ago.4 Even understanding what needs to change can be a complex problem, and not all of the work can be known at the start. If you look closely at the design documentation, you might find that it postpones or hand-waves the key decisions that need the most alignment.

That’s a more realistic project description. No matter how carefully you overlay teams onto a huge project, some responsibilities end up not being owned by anyone, and others are claimed by two teams. Information fails to flow or gets mangled in translation and causes conflict. Teams make excellent local maximum decisions and software projects get stuck.

One way to keep a project moving is to have someone who feels ownership for the whole thing, rather than any of its individual parts. Even before the project kicks off, that person can scope out the work and build a proposal. Once the project is underway, they’re likely to be the author or coauthor of the high-level system design and a main point of contact for it. They maintain a high engineering standard, using their experience to anticipate risks and ask hard questions. They also spend time informally mentoring or coaching—or just setting a good example for—the leads of individual parts of the project. When the project gets stuck, they have enough perspective to track down the causes and unblock it (more on that in Chapter 6). Outside the project, they’re telling the story of what’s happening and why, selling the vision to the rest of the company, and explaining what the work will make possible and how the new project affects everyone.

Why can’t technical program managers (TPMs) do this consensus-building and communication? There is definitely some overlap in responsibilities. Ultimately, though, TPMs are responsible for delivery, not design, and not engineering quality. TPMs make sure the project gets done on time, but staff engineers make sure it’s done with high engineering standards. Staff engineers are responsible for ensuring the resulting systems are robust and fit well with the technology landscape of the company. They are cautious about technical debt and wary of anything that will be a trap for future maintainers of those systems. It would be unusual for TPMs to write technical designs or set project standards for testing or code review, and no one expects them to do a deep dive through the guts of a legacy system to make a call on which teams will need to integrate with it. When a staff engineer and TPM work well together on a big project, they can be a dream team.

Why Do We Need Engineers Who Are a Good Influence?

Software matters. The software systems we build can affect people’s well-being and income: Wikipedia’s list of software bugs makes for good, if sobering, reading. We’ve learned from plane crashes, ambulance system failures, and malfunctioning medical equipment that software bugs and outages can kill people, and it would be naive to assume there won’t be more and bigger software-related tragedies coming in our future.5 We need to take software seriously.

Even when the stakes are lower, we’re still making software for a reason. With a few R&D-ish exceptions, engineering organizations usually don’t exist just for the sake of building more technology. They’re setting out to solve an actual business problem or to create something that people will want to use. And they’d like to achieve that with some acceptable level of quality, an efficient use of resources, and a minimum of chaos.

Of course, quality, efficiency, and order are far from guaranteed, particularly when there are deadlines involved. When doing it “right” means going slower, teams that are eager to ship may skip testing, cut corners, or rubber-stamp code reviews. And creating good software isn’t easy or intuitive. Teams need senior people who have honed their skills, who have seen what succeeds and what fails, and who will take responsibility for creating software that works.

We learn from every project, but each of us has only a finite number of experiences to reflect on. That means that we need to learn from each other’s mistakes and successes, too. Less experienced team members might never have seen good software being made, or might see producing code as the only important skill in software engineering. More seasoned engineers can have huge impact by conducting code and design reviews, providing architectural best practices, and creating the kinds of tooling that make everyone faster and safer.

Staff engineers are role models. Managers may be responsible for setting culture on their teams, enforcing good behavior, and ensuring standards are met. But engineering norms are set by the behavior of the most respected engineers on the project. No matter what the standards say, if the most senior engineers don’t write tests, you’ll never convince everyone else to do it. These norms go beyond technical influence: they’re cultural, too. When senior people vocally celebrate other people’s work, treat each other with respect, and ask clarifying questions, it’s easier for everyone else to do that too. When early-career engineers respect someone as the kind of engineer they want to “grow up” to be, that’s a powerful motivator to act like they do. (Chapter 7 will explore leveling up your organization by being a role model.)

Maybe now you’re convinced that engineers should do this big-picture, big-project, good-influence stuff, but here’s the problem: they can’t do it on top of the coding workload of a senior engineer. Any hour you’re writing strategy, reviewing project designs, or setting standards, you’re not coding, architecting new systems, or doing a lot of the work a software engineer might be evaluated on. If a company’s most senior engineers just write code all day, the codebase will see the benefit of their skills, but the company will miss out on the things that only they can do. This kind of technical leadership needs to be part of the job description of the person doing it. It isn’t a distraction from the job: it is the job.

Enough Philosophy. What’s My Job?

The details of a staff engineering role will vary. However, there are some attributes of the job that I think are fairly consistent. I’ll lay them out here, and the rest of the book will take them as axiomatic.

You’re Not a Manager, but You Are a Leader

First things first: staff engineering is a leadership role. A staff engineer often has the same seniority as a line manager. A principal engineer often has the seniority of a director. As a staff+ engineer, you’re the counterpart of a manager at the same level, and you’re expected to be as much “the grown-up in the room” as they are. You may even find that you’re more senior and more experienced than some of the managers in your organization. Whenever there’s a feeling of “someone should do something here,” there’s a reasonable chance that the someone is you.

Do you have to be a leader? Midlevel engineers sometimes ask me if they really need to get good at “that squishy human stuff” to go further. Aren’t technical skills enough? If you’re the sort of person who got into software engineering because you wanted to do technical work and don’t love talking to other humans, it can feel unfair that your vocation runs into this wall. But if you want to keep growing, being deep in the technology can only take you so far. Accomplishing larger things means working with larger groups of people—and that needs a wider set of skills.

As your compensation increases and your time becomes more and more expensive, the work you do is expected to be more valuable and have a greater impact. Your technical judgment will need to include the reality of the business and whether any given project is worth doing at all. As you increase in seniority, you’ll take on bigger projects, projects that can’t succeed without collaboration, communication, and alignment; your brilliant solutions are just going to cause you frustration if you can’t convince the other people on the team that yours is the right path to take. And whether you want to or not, you’ll be a role model: other engineers will look to those with the big job titles to understand how to behave. So, no: you can’t avoid being a leader.

Staff engineers lead differently than managers, though. A staff engineer usually doesn’t have direct reports. While they’re involved and invested in growing the technical skills of the engineers around them, they’re not responsible for managing anyone’s performance or approving vacation or expenses. They can’t fire or promote—though local team managers should value their opinions about other team members’ skills and output. Their impact happens in other ways.

Leadership comes in lots of forms that you might not immediately recognize as such. It can come from designing “happy path” solutions that protect other engineers from common mistakes. It can come from reviewing other engineers’ code and designs in a way that improves their confidence and skills, or from highlighting that a design proposal doesn’t meet a genuine business need. Teaching is a form of leadership. Quietly raising everyone’s game is leadership. Setting technical direction is leadership. Finally, there’s having the reputation as a stellar technologist that can inspire other people to buy into your plans just because they trust you. If that sounds like you, then guess what? You’re a leader.

You’re in a “Technical” Role

Staff engineering is a leadership role, but it’s also a deeply specialized one. It needs technical background and the kinds of skills and instincts that come from engineering experience. To be a good influence, you need to have high standards for what excellent engineering looks like and model them when you build something. Your reviews of code or designs should be instructive for your colleagues and should make your codebase or architecture better. When you’re making technical decisions, you need to understand the trade-offs and help other people understand them too. You need to be able to dive into the details where necessary, ask the right questions, and understand the answers. When arguing for a particular course of action, or a particular change in technical culture, you need to know what you’re talking about. So you have to have a solid foundation of technical skills.

This doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll write a lot of code. At this level, your goal is to solve problems efficiently, and programming will often not be the best use of your time. It may make more sense for you to take on the design or leadership work that only you can do and let others handle the programming. Staff engineers often take on ambiguous, messy, difficult problems and do just enough work on them to make them manageable by someone else. Once the problem is tractable, it becomes a growth opportunity for less experienced engineers (sometimes with support from the staff engineer).

For some staff engineers, deep diving through codebases will remain the most efficient tool to solve many problems. For others, writing documents might get better results, or becoming a master of data analysis, or having a terrifying number of one-on-one meetings. What matters is that the problems get solved, not how.6

You Aim to Be Autonomous

When you started out as an engineer, your manager probably told you what to work on and how to approach it. At senior level, maybe your manager advised you on which problems were important to solve, and left it to you to figure out what to do about it. At staff+ levels, your manager should be bringing you information and sharing context, but you should be telling them what’s important just as much as the other way around. As Sabrina Leandro, principal engineer at Intercom, asks, “So you know you’re supposed to be working on things that are impactful and valuable. But where do you find this magic backlog of high-impact work that you should be doing?” Her answer: “You create it!”

As a senior person in the organization, it’s likely that you’ll be pulled in many directions. It’s up to you to defend and structure your time. There are a finite number of hours in the week (see Chapter 4). You get to choose how to spend them. If someone asks you to work on something, you’ll bring your expertise to the decision. You’ll weigh the priority, the time commitment, and the benefits—including the relationship you want to maintain with the person who asked you for help—and you’ll make your own call. If your CEO or other local authority figure tells you they need something done, you’ll give that appropriate weight. But autonomy demands responsibility. If the thing they asked you to work on turns out to be harmful, you have a responsibility to speak up. Don’t silently let a disaster unfold. (Of course, if you want to be listened to, you’ll have to have built up a reputation for being trustworthy and correct.)

You Set Technical Direction

As a technical leader, part of a staff engineer’s role is to make sure the organization has a good technical direction. Underlying the product or service your organization provides is a host of technical decisions: your architecture, your storage systems, the tools and frameworks you use, and so on. Whether these decisions are made at a team level or across multiple teams or whole organizations, part of your job is to make sure that they get made, that they get made well, and that they get written down. The job is not to come up with all (or even necessarily any!) of the aspects of the technical direction, but to ensure there is an agreed-upon, well-understood solution that solves the problems it sets out to solve.

Understanding Your Role

Those axioms should help you to start defining your role, but you’ll notice that they leave out a lot of implementation details! The truth is that the day-to-day work of one staff engineer might look very different from that of another. The realities of your role will depend on the size and needs of your company or organization, and will also be influenced by your personal work style and preferences.

This variation means that it can be hard to compare your work to that of staff engineers around you or in other companies. So in this section, we’re going to unpack some of the role’s more variable attributes.

Let’s start with reporting chains.

Where in the Organization Do You Sit?

Our industry hasn’t settled on any standard model for how staff+ engineers report into the rest of the engineering organization. Some companies have their most senior engineers report to a chief architect or the office of the CTO; others assign them to directors of various organizations, to managers at various levels, or to a mix of all of the above. There’s no one right answer here, but there can be a lot of wrong answers, depending on what you’re trying to achieve.

Reporting chains (see the example in Figure 1-3) will affect the level of support you receive, the information you’re privy to, and, in many cases, how you’re perceived by colleagues outside your group.

Figure 1-3. Staff+ engineers reporting in at different levels of the org hierarchy. Even if these engineers are all at the same level of seniority, A will find it much easier to have organizational context and to be in director-level conversations than D will.

Reporting “high”

Reporting “high” in the org chart, such as to a director or VP, will give you a broad perspective. The information you get will be high-level and impactful, and so will the problems you’re asked to solve. If you’re reporting to a very competent senior person, watching them make decisions, run meetings, or navigate a crisis can be a unique and valuable learning experience.

That said, you’ll probably get a lot less of your manager’s time than you would if you had a local manager. Your manager might have less visibility into your work and therefore might not be able to advocate for you or help you grow. An engineer working closely with a single team but reporting to a director may feel disconnected from the rest of the team or might pull the director’s attention into local disagreements that should have been solved at the team level.

If you find that your manager isn’t available, doesn’t have time to understand the work that you do, or gets pulled into low-level technical decisions that aren’t a good use of their time, consider that you might be happier with a manager whose focus is more aligned with yours.

Reporting “low”

Reporting to a manager lower in the org chart brings its own set of advantages and disadvantages. Chances are that you’ll get more focused attention from your manager, and you’ll be more likely to have an advocate. If you prefer to focus on a single technical area, you might benefit from working with a manager who is close to that area.

But an engineer assigned to a single team may find it hard to influence the whole organization. Like it or not, humans pay attention to status and hierarchies—and reporting chains. You’re likely to have much less influence if you’re reporting to a line manager. The information you get is also prone to be more filtered and centered on the problems of that specific team. If your manager doesn’t have access to some piece of information, you almost certainly won’t either.

Reporting to a line manager may also mean that you’re reporting to someone less experienced than you are. That’s not inherently a problem, but you may have less to learn from your manager, and they might not be helpful for career development: chances are that they won’t know how to help you. All of this may be fine if you’re getting some of your management needs met elsewhere.7 In particular, if you’re reporting to someone low in the org hierarchy, make sure to have skip-level meetings with your manager’s manager.8 Find ways to stay connected to your organization’s goals.

If you and your manager have different ideas about how you can be most effective, that can cause tension. You can end up with a case of the local maximum issues I mentioned earlier, where your manager wants you to work on the most important concern of the team, when there are far bigger problems inside the organization that need you more. It’s harder for a technical or prioritization debate to happen on a truly level playing field when one person is responsible for the other’s performance rating and compensation. If you find that these arguments are happening a lot, you might want to advocate to report to a level higher.

What’s Your Scope?

Your reporting chain will likely affect your scope: the domain, team, or teams that you pay close attention to and have some responsibility for, even if you don’t hold any formal leadership role in this domain.

Inside your scope, you should have some influence on short-term and long-term goals. You should be aware of the major decisions being made. You should have opinions about changes and represent people who don’t have the leverage to prevent poor technical decisions that affect them. You should be thinking about how to cultivate and develop the next generation of senior and staff engineers, and should notice and suggest projects and opportunities that would help them grow.

In some cases, your manager might expect you to devote the majority of your skills and energy to solving problems that fall within their domain. In other cases, a team may just be a home base as you spend some portion of your time on fires or opportunities elsewhere in the org. If you report to a director, there may be an implicit assumption that you operate at a high level and tie together the work of everything that’s happening in the org, or you might be explicitly allocated to some subset of the director’s teams or technology areas. Be clear about which it is.

Be prepared to ignore your scope when there’s a crisis: there is no such thing as “not my job” during an outage, for example. You should also have a level of comfort with stepping outside your day-to-day experience, leading when needed, learning what you need to learn, and fixing what you need to fix. Part of the value of a staff engineer is that you don’t stay in your lane.

Nonetheless, I recommend that you get very clear on what your scope is, even if it’s temporary and subject to change.

A scope too broad

If your scope is too broad (or undefined), there are a few possible failure modes.

- Lack of impact

- If anything can be your problem, then it’s easy for everything to become your problem, particularly if you’re in an organization with fewer senior people than it needs. There will always be another side quest: in fact, it’s all too easy to create a role that’s entirely side quests, with no real goal at all.9 Beware of spreading yourself too thin. You can end up without a narrative to your work that makes you (and whoever hired you) feel like you achieved something.

- Becoming a bottleneck

- When there’s a senior person who is seen to do everything, the convention can become that they need to be in the room for every decision. Rather than speeding up your organization, you end up slowing them down because they can’t manage without you.

- Decision fatigue

- If you escape the trap of trying to do everything, you’ll have the constant cost of deciding which things to do. I’ll talk in Chapter 4 about choosing your work.

- Missing relationships

- If you’re working with a very broad set of teams, it’s harder to have enough regular contact to build the sorts of friendly relationships that make it easier to get things done (and that make work enjoyable!). Other engineers also lose out: they don’t get the sort of mentorship and support that comes from having a “local” staff engineer involved in their work.

It’s hard to operate in a workplace where you can do literally anything. Better to choose an area, build influence, and have some successes there. Devote your time to solving some problems entirely. Then, if you’re ready to, move on to a different area.

A scope too narrow

Beware, too, of scoping yourself too narrowly. A common example is when a staff engineer is part of a single team, reporting to a line manager. Managers might really like this—they get a very experienced engineer who can do a large percentage of the design and technical planning, and perhaps serve as a technical leader or team lead for a project. Some engineers will love this too: it means you get to go really deep on the team’s technologies and problems and understand all of the nuances. But watch out for the risks of a scope that’s too narrow:

- Lack of impact

- It’s possible to spend all of your time on something that doesn’t need the expertise and focus of a staff engineer. If you choose to go really deep on a single team or technology, it should be a core component, a mission-critical team, or something else that’s very important to the company.

- Opportunity cost

- Staff engineers’ skills are usually in high demand. If you’re assigned to a single team, you may not be top of mind for solving a problem elsewhere in the org, or your manager may be unwilling to let you go.

- Overshadowing other engineers

- A narrow scope can mean that there’s not enough work to keep you busy, and that you may overshadow less experienced people and take learning opportunities away from them. If you always have time to answer all of the questions and take on all of the tricky problems, nobody else gets experience in doing that.

- Overengineering

- An engineer who’s not busy can be inclined to make work for themselves. When you see a vastly overengineered solution to a straightforward problem, that’s often the work of a staff engineer who should have been assigned to a harder problem.

Some technical domains and projects are deep enough that an engineer can spend their whole career there and never run out of opportunities. Just be very clear about whether you’re in one of those spaces.

What Shape Is Your Role?

So long as it’s generally agreed that your work is impactful, you should have a lot of flexibility around how you do it. That includes a certain amount of defining what your job is. Here are a few questions to ask yourself:

Do you approach things depth-first or breadth-first?

Do you prefer to focus narrowly on a single problem or technology area? Or are you more inclined to go broad across multiple teams or technologies, focusing on a single problem only when it can’t be solved without you? Being depth-first or breadth-first is very much about your personality and work style.

There’s no wrong answer here, but you’ll have an easier and more enjoyable time if your preference here is lined up with your scope. For instance, if you want to influence the technical direction of your org or business, you’ll find yourself gravitating toward opportunities to take a broader view. You’ll need to be in the rooms where the decisions are happening and tackle problems that affect many teams. If you’re trying to do that while assigned to a single deep architectural problem, no one wins. On the other hand, if you’re aiming to become an industry expert in a particular technical domain, you’ll need to be able to narrow your focus and spend most of your time in that one area.

Which of the “four disciplines” do you gravitate toward?

Yonatan Zunger, distinguished engineer at Twitter, describes the four disciplines that are needed in any job in the world:

- Core technical skills

- Coding, litigation, producing content, cooking—whatever a typical practitioner of the role works on

- Product management

- Figuring out what needs to be done and why, and maintaining a narrative about that work

- Project management

- The practicalities of achieving the goal, removing chaos, tracking the tasks, noticing what’s blocked, and making sure it gets unblocked

- People management

- Turning a group of people into a team, building their skills and careers, mentoring, and dealing with their problems

Zunger notes that the higher your level, the less your mix of these skills corresponds with your job title: “The more senior you get, the more this becomes true, the more and more there is an expectation that you can shift across each of these four kinds of jobs easily and fluidly, and function in all rooms.”

Every team and every project needs all four of these skills. As a staff engineer, you’ll use all of them. You don’t need to be amazing at all of them, though. We all have different aptitudes and enjoy or avoid different kinds of work. Maybe it’s obvious to you which ones you enjoy and which you hope to never need. If you’re not sure, Zunger suggests discussing each one with a friend and having them watch your emotional response and energy while you talk about it. If there’s one that you really hate, make sure you’re working with someone who’s eager to do that aspect of the work. Whether you’re breadth-first or depth-first, you’ll find it hard to continue to grow with only the core technical skills.

How much do you want (or need) to code?

For “coding” here, feel free to swap in the core technical work of your career so far. This set of skills probably got you to where you are today, and it can be uncomfortable to feel that you’re getting rusty or out of date. Some staff engineers find that they end up reading or reviewing a lot of code but not writing much at all. Others are core contributors to projects, coding every day. A third group finds reasons to code, taking on noncritical projects that will be interesting or educational but won’t delay the project.

If you’re going to feel antsy unless you’re in code every day, make sure you’re not taking on a broad architectural or influence-based role where you just won’t have time. Or at least have a plan for how you’re going to scratch that itch, so you’ll be able to resist jumping on coding tasks and leaving the bigger problems to fend for themselves.

How’s your delayed gratification?

Coding has comfortingly fast feedback cycles: every successful compile or test run tells you how things are going. It’s like a tiny performance review every day! It can be disheartening to move toward work that doesn’t have any built-in feedback loops to tell you whether you’re on the right path.

On a long-term or cross-organizational project, or with strategy or culture change, it can be months—or even longer—before you have a strong signal about whether what you’re doing is working. If you’re going to be anxious and stressed out on a project with longer feedback cycles, ask a manager who you trust to tell you, regularly and honestly, how things are going. If you need that and don’t have it, consider projects that pay off on a shorter timescale.

Are you keeping one foot on the manager track?

Although most staff engineers don’t have direct reports, some do. A tech lead manager (TLM), sometimes called a team lead, is a kind of hybrid role where the staff engineer is the technical leader for a team and also manages that team. It’s a famously difficult gig. It can be challenging to be responsible for both the humans and the technical outcomes without feeling like you’re failing at one or the other. It’s also difficult to find time to invest in building skills on either side, and I’ve heard TLM folks lament a loss of career progression as a result.

Some people take a management role for a couple of years, then a staff engineer role, going back and forth every so often to keep their skills sharp on both sides.10 We’ll look more at this “pendulum” and at TLM roles in Chapter 9.

Do any of these archetypes fit you?

In his article “Staff Archetypes”, Will Larson describes four distinct patterns he’s seen staff engineering roles take. You can use these archetypes as you define the kind of role you have, or would like to have:

- Tech leads

- Partner with managers to guide the execution of one or more teams.

- Architects

- Responsible for technical direction and quality across a critical area.

- Solvers

- Wade into one difficult problem at a time.

- Right hands

- Add leadership bandwidth to an organization.

If you don’t see yourself in any of those archetypes, or your role crosses more than one of them, that’s OK! These archetypes are not intended to be prescriptive; they give us concepts to use in articulating how we prefer to work.

What’s Your Primary Focus?

So we’ve discussed your scope and your reporting chain: the rough boundaries of the part of the organization you’re operating inside, and where in the organization you sit. We’ve also looked at your aptitudes: how you like to work and what kinds of skills you’re drawn to. But even if you understand all of that and have a clear picture of the shape of your role, there’s one question left: what are you going to work on?

As you grow in influence, you’ll find that more and more people want you to care about things. Someone’s putting together a best practices document for how your organization does code review, and they want your opinion. Your group is doing a hiring push and needs help deciding what to interview for. There’s a deprecation that would be making more progress if it had a staff engineer drumming up senior sponsorship. And that’s just Monday morning. What do you do?

In some cases, your manager or someone they report to will have strong opinions about where you should focus, or will even have hired you specifically to solve a particular problem. Most of the time, though, you’ll have some autonomy in deciding what’s most important. Every time you choose what to work on, you’re also choosing what not to do, so be deliberate and thoughtful about what you take on.

What’s important?

Early in your career, if you do a great job on something that turns out to be unnecessary, you’ve still done a great job. At the staff engineer level, though, everything you do has a high opportunity cost, so your work needs to be important.

Let’s unpack that for a moment. “Your work needs to be important” doesn’t mean you should only work on the fanciest, most glamorous technologies and VP-sponsored initiatives. The work that’s most important will often be the work that nobody else sees. It might be a struggle to even articulate the need for it, because your teams don’t have good mental models for it yet. It might involve gathering data that doesn’t exist, or spelunking through dusty code or documents that haven’t been touched in a decade. There are any number of other grungy tasks that just need to get done. Meaningful work comes in many forms.

Know why the problem you’re working on is strategically important—and if it’s not, do something else.

What needs you?

There’s a similar situation when a senior person devotes themself to the sort of coding project that any midlevel engineer could have taken on: you’re going to do a stellar job on it, but chances are there’s a senior-sized problem available that the midlevel engineer wouldn’t be able to tackle. To use an idiom my kid dropped profoundly one day, “You don’t plant grass in your only barrel.”

Be wary of choosing a project that already has a lot of senior people on it. Scope out who else is working on the problem and whether they seem likely to succeed at solving it. Some projects may even be slowed by an extra leader joining.11 In general, if there are more people being the wise voice of reason than there are people actually typing code (or whatever your project’s equivalent is), don’t butt in. Try to choose a problem that actually needs you and that will benefit from your attention. Chapter 4 will give you some tools for deciding which projects to take on.

Aligning on Scope, Shape, and Primary Focus

By now, you should have a pretty clear picture of what the scope of your role is, how it’s shaped, and what you’re working on right now. But are you certain that your picture matches everyone else’s? Your manager’s and colleagues’ expectations may differ wildly from yours on what a staff engineer is, what authority you have to make decisions, and myriad other big questions. If you’re joining a company as a staff engineer, it’s best to get all of this straightened out up front.

A technique I learned from my friend Cian Synnott is to write out my understanding of my job and share it with my manager. It can feel a little intimidating to answer the question “What do you do here?” What if other people think what you do is useless, or think you don’t do it well? But writing it out removes the ambiguity, and you’ll find out early if your mental model of the role is the same as everyone else’s. Better now than at performance review time.

Here’s what such a role description might look like for Ali, a breadth-first architect-archetype staff engineer, who is assisting with (but not leading) a large cross-team project.

Don’t obsess about getting this perfect: get it right enough. Describing your goals doesn’t mean you’re forbidden from doing something else. But it’s a nice reminder of what you intended to do, and it helps you keep an eye on whether you’re actually doing the thing you claimed was your job.

You might decide that your focus needs to change earlier than you expected. The state of the world can change or your priorities might shift. If so, write a new role description with the new information. Being clear about your expectations of yourself makes sure everyone’s on the same page.

Is That Your Job?

Your job is to make your organization successful. You might be a technology expert or a coder or affiliated with a specific team, but ultimately your job is to help your organization achieve its goals. Senior people do a lot of things that are not in their core job description. They can end up doing things that make no sense in anyone’s job description! But if that’s what the project needs to be successful, consider doing it.

Some of my coworkers at Squarespace tell the story of the day in 2012 when their data center had a power outage and they carried fuel up 17 flights of stairs to keep it online. “Hauling barrels of diesel” does not show up in most tech job descriptions, but that’s what was needed to keep the site online (and it worked!). When the machine room flooded at the ISP I worked at years ago, the job became about making a bucket chain of trash cans to keep the water level low. And when a Google project in 2005 was running late and we didn’t have enough hardware folks available, my job for a couple of days was racking servers in a data center in San Jose. You do what you need to do to make the project happen.

Usually this “not my job” work is less dramatic, of course. It can mean having a dozen conversations to unblock a project your team depends on, or noticing that your new engineer is lost and checking in with them. To reiterate: your job is ultimately whatever your organization or company needs it to be. In the next chapter, I’ll talk about how to understand what those needs are.

To Recap

Staff engineering roles are ambiguous by definition. It’s up to you to discover and decide what your role is and what it means for you.

You’re probably not a manager, but you’re in a leadership role.

You’re also in a role that requires technical judgment and solid technical experience.

Be clear about your scope: your area of responsibility and influence.

Your time is finite. Be deliberate about choosing a primary focus that’s important and that isn’t wasting your skills.

Align with your management chain. Discuss what you think your job is, see what your manager thinks it is, understand what’s valued and what’s actually useful, and set expectations explicitly. Not all companies need all shapes of staff engineers.

Your job will be a weird shape sometimes, and that’s OK.

1 I also recommend progression.fyi, which has an extensive collection of ladders published by various tech companies.

2 One company I heard about used the levels “senior,” “staff,” and “principal,” in that order of seniority, but got acquired by another company that used “senior,” “principal,” and “staff.” Chaos. The acquiring company changed all “staff” to “principal” and all “principal” to “staff,” and no one was happy. Both staffs and principals saw the change as a demotion. Titles matter!

3 I like my friend Tiarnán de Burca’s definition of senior engineer: the level at which someone can stop advancing and continue their current level of productivity, capability, and output for the rest of their career and still be “regretted attrition” if they leave.

4 What were they thinking? Was this really what they intended to do? Of course, future teams will ask the same of us.

5 Hillel Wayne’s essay “We Are Not Special” points out that a lot of engineering solutions that used to involve carefully tuning physical equipment are now done with a “software kludge” instead. I’m genuinely always surprised we’ve had so few major fatal accidents from software so far. I wouldn’t like to depend on us staying lucky.

6 This is why I’m not a fan of giving experienced staff engineers coding interviews. If you’ve made it to this level, either you can code well or you’ve learned to solve technical problems using your other muscles. The outcomes are what matters.

7 I recommend Lara Hogan’s article on building a “manager Voltron.”

8 If skip-level meetings aren’t common in your company, you may need to be clear that you’re not looking to undermine or “report” on your manager; you want to understand the wider group’s priorities and make the connections that can help you have the most impact. Ideally, your manager will understand the value of skip-level meetings and help you set them up.

9 A side quest is a part of a video game that doesn’t have anything to do with the main mission, but that you can optionally do for coins or experience points or just for fun. Picture lots of, “Well, I was about to fight my way into the heavily guarded fortress to defeat the demon that’s been terrorizing this land, but sure, I can go find your cat first.”

10 Charity Majors’s “The Engineer/Manager Pendulum” is an excellent article on this topic.

11 You’ll hear Brooks’s Law quoted: “Adding manpower to a late software project makes it later.” While Brooks himself called this “an outrageous simplification”, there’s truth to it. See The Mythical Man-Month by Fred Brooks (Addison-Wesley).

Get The Staff Engineer's Path now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.