Basic Parts of a Mail Message

In this section, we will examine the three parts that make up a mail message: the header, body, and envelope. But before we do, we must first demonstrate how to run sendmail by hand so that you can see what a message’s parts look like.

Run sendmail by Hand

Most users do not run sendmail directly. Instead, they use one of many MUAs to compose a mail message. Those programs invisibly pass the mail message to sendmail, creating the appearance of instantaneous transmission. The sendmail program then takes care of delivery in its own seemingly mysterious fashion.

Although most users don’t run sendmail directly, it is perfectly legal to do so. You, like many system managers, might need to do this to track down and solve mail problems.

Here’s a demonstration of one way to run sendmail by hand. First create a file named sendstuff with the following contents:

This is a one-line message.

Second, mail this file to yourself with the following command line,

where you is your login name:

%/usr/sbin/sendmailyou<sendstuff

Here, you run sendmail directly by specifying

its full pathname.[2] When you run

sendmail, any command-line arguments that do not

begin with a - character are considered to be the

names of the people to whom you are sending the mail message.

The <sendstuff sequence causes the contents of

the file that you have created (sendstuff) to be

redirected into the sendmail program. The

sendmail program treats everything it reads from

its standard input (up to the end of the file) as the mail message to

transmit.[3]

Now view the mail message you just sent. How you do this will vary. Many users just type mail to view their mail. Others use the mh(1) package and type inc to receive and show to view their mail. No matter how you normally view your mail, save the mail message you just received to a file. It will look something like this:

From you@Here.US.EDU Fri Dec 13 08:11:44 2002

Received: (from you@localhost)

by Here.US.EDU (8.12.7/8.12.7)

id d8BILug12835 for you; Fri, 13 Dec 2002 08:11:44 -0600 (MDT)

Date: Fri, 13 Dec 2002 08:11:43

From: you@Here.US.EDU (Your Full Name)

Message-Id: 200201011548.d872mLW24467@Here.US.EDU>

To: you ← might be something else (see NoRecipientAction)

This is a one-line message.The first thing to note is that this file begins with seven lines of text that were not in your original message. Those lines were added by sendmail and your local delivery program and are called the header.

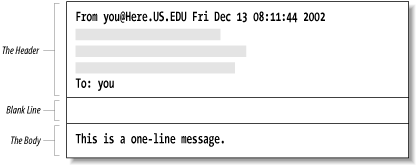

The last line of the file is the original line from your sendstuff file. It is separated from the header by one blank line. The body of a mail message comes after the header and consists of everything that follows the first blank line (see Figure 1-1).

Ordinarily, when you send mail with your MUA, the MUA adds a header and feeds both the header and the body to sendmail. This time, however, you ran sendmail directly and supplied only a body; the header was added by sendmail.

The Header

Let’s examine the header in more detail.

From you@Here.US.EDU Fri Dec 13 08:11:44 2002

Received: (from you@localhost)

by Here.US.EDU (8.12.7/8.12.7)

id d8BILug12835 for you; Fri, 13 Dec 2002 08:11:44 -0600 (MDT)

Date: Fri, 13 Dec 2002 08:11:43

From: you@Here.US.EDU (Your Full Name)

Message-Id: 200201011511.d872mLW24467@Here.US.EDU>

To: you ← might be something else (see NoRecipientAction)Notice that most header lines start with a word followed by a colon.

Each word tells what kind of information the rest of the line

contains. Many types of header lines can appear in a mail message.

Some are mandatory, some are optional, and some can appear many

times. Those that appeared in the message you mailed to yourself were

all mandatory.[4] That’s why

sendmail added them to your message. The line

starting with the five characters

"From " (the

fifth character is a space) is added by some programs (such as

/bin/mail) but not by others (such as

mh).

A Received: line is added each time a machine

receives the mail message. (If there are too many such lines, the

mail message will bounce—because it is

probably in a loop—and will be returned to the sender as failed

mail.) The indented line is a continuation of the line above, the

Received: line. The Date: line

gives the date and time when the message was originally sent. The

From: line lists the email address and the full

name of the sender. The Message-ID: line is like a

serial number in that it is guaranteed to uniquely identify the mail

message. And the To:[5] line shows a

list of one or more recipients. (Multiple recipients would be

separated with commas.)

A complete list of all header lines that are of importance to sendmail is presented in Chapter 25. The important concept here is that the header precedes, and is separate from, the body in all mail messages.

The Body

The body of a mail message consists of everything following the first blank line to the end of the file. When you sent your sendstuff file, it contained only a body. Now, edit the file sendstuff and add a small header:

Subject: a test ←add

←add

This is a one-line message.The Subject: header line is optional. The

sendmail program passes it through as is. Here,

the Subject: line is followed by a blank line and

then the message text, forming a header and a body. Note that a blank

line must be truly blank. If you put space or tab characters in it,

thus forming an “empty-looking”

line, the header will not be separated from the

body as intended.

Send this file to yourself again, running sendmail by hand as you did before:

%/usr/sbin/sendmailyou<sendstuff

Notice that our Subject: header line was carried

through without change:

From you@Here.US.EDU Fri Dec 13 08:11:44 2002

Received: (from you@localhost)

by Here.US.EDU (8.12.7/8.12.7)

id d8BILug12835 for you; Fri, 13 Dec 2002 08:11:44 -0600 (MDT)

Date: Fri, 13 Dec 2002 08:11:43

From: you@Here.US.EDU (Your Full Name)

Message-Id: 200201011511.d9BMTuX29709@Here.US.EDU>

Subject: a test ←note

To: you

This is a one-line message.The Envelope

So that it can more easily handle delivery to diverse recipients, the sendmail program uses the concept of an envelope. This envelope is analogous to the physical envelopes that are used for post office mail. Imagine you want to send two copies of a document, one to your friend in the office next to yours and one to a friend across the country:

To: friend1, friend2@remote

After you photocopy the document, you stuff each copy into a separate

envelope. You hand one envelope to a clerk, who carries it next door

and hands it to friend1 in the next office. This

is like delivery on your local machine. The clerk drops the other

copy in the slot at the corner mailbox, and the post office forwards

that envelope across the country to

friend2@remote. This is like

sendmail transporting a mail message to a remote

machine.

To illustrate what an envelope is, consider one way in which sendmail might run /usr/lib/mail.local, a program that performs local delivery:

deliver to friend1's mailbox ↓ /usr/lib/mail.local -d friend1 ←sendmail runs ↑the envelope recipient

Here sendmail runs

/usr/lib/mail.local with a

-d, which tells

/usr/lib/mail.local to append the mail message

to friend1’s mailbox.

Information that describes the sender or recipient, but is not part of the message header, is considered envelope information. The two might or might not contain the same information (a point we’ll gloss over for now). In the case of /usr/lib/mail.local, the email message showed two recipients in its header:

To: friend1, friend2@remote ←the header

But the envelope information that is given to /usr/lib/mail.local showed only one (the one appropriate to local delivery):

-d friend1 ←specifies the envelope

Now consider the envelope of a message transported over the network. When sending network mail, sendmail must give the remote site the envelope-sender address and a list of recipients separate from and before it sends the mail message (header and body). Figure 1-2 shows this in a greatly simplified conversation between the local sendmail and the remote machine’s sendmail.

The local sendmail tells the remote

machine’s sendmail that there

is mail from you (the envelope-sender) and for

friend2@remote. It conveys this envelope-sender

and recipient information separate from and

before it transmits the mail message that contains the

header. Because this information is conveyed separately from the

message header, it is called the envelope.

Only one recipient is listed in the envelope, whereas two were listed in the message header:

To: friend1, friend2@remote

The remote machine should not need to know about the local user,

friend1, so that bit of recipient information is

excluded from the envelope.

A given mail message can be sent by using many different envelopes (like the two here), but the header will be common to them all. But note that the headers of a message don’t necessarily reflect the actual envelope. You witness such mismatches whenever you receive a message from a mailing list, or receive a spam message.

[2] That path might be different on your system. If so, substitute the correct pathname in all the examples that follow. For example, try looking for sendmail in /usr/lib or /usr/ucblib.

[3] We are fudging for simplicity here. If the

file contains a line that contains only a single dot, that line will

be treated as if it marks the end of the file. If you need to include

such a line as part of literal input, use the

IgnoreDots options (IgnoreDots).

[4] We are fudging for simplicity. The

Message-ID: header is not strictly

mandatory.

[5] Depending on

how the NoRecipientAction option was set, this

could be an Apparently-To: header, a

Bcc: header, or even a To:

header followed by an

"undisclosed-recipients:;"

(see NoRecipientAction).

Get Sendmail, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.