Chapter 4. Functions

In the last chapter we covered the basics of TypeScript’s type system: primitive types, objects, arrays, tuples, and enums, as well as the basics of TypeScript’s type inference and how type assignability works. You are now ready for TypeScript’s pièce de résistance (or raison d’être, if you’re a functional programmer): functions. A few of the topics we’ll cover in this chapter are:

-

The different ways to declare and invoke functions in TypeScript

-

Signature overloading

-

Polymorphic functions

-

Polymorphic type aliases

Declaring and Invoking Functions

In JavaScript, functions are first-class objects. That means you can use them exactly like you would any other object: assign them to variables, pass them to other functions, return them from functions, assign them to objects and prototypes, write properties to them, read those properties back, and so on. There is a lot you can do with functions in JavaScript, and TypeScript models all of those things with its rich type system.

Here’s what a function looks like in TypeScript (this should look familiar from the last chapter):

functionadd(a:number,b:number){returna+b}

You will usually explicitly annotate function parameters (a and b in this example)—TypeScript will always infer types throughout the body of your function, but in most cases it won’t infer types for your parameters, except for a few special cases where it can infer types from context (more on that in “Contextual Typing”). The return type is inferred, but you can explicitly annotate it too if you want:

functionadd(a:number,b:number):number{returna+b}

Note

Throughout this book I’ll explicitly annotate return types where it helps you, the reader, understand what the function does. Otherwise I’ll leave the annotations off because TypeScript already infers them for us, and why would we want to repeat work?

The last example used named function syntax to declare the function, but JavaScript and TypeScript support at least five ways to do this:

// Named functionfunctiongreet(name:string){return'hello '+name}// Function expressionletgreet2=function(name:string){return'hello '+name}// Arrow function expressionletgreet3=(name:string)=>{return'hello '+name}// Shorthand arrow function expressionletgreet4=(name:string)=>'hello '+name// Function constructorletgreet5=newFunction('name','return "hello " + name')

Besides function constructors (which you shouldn’t use unless you are being chased by bees because they are totally unsafe),1 all of these syntaxes are supported by TypeScript in a typesafe way, and they all follow the same rules around usually mandatory type annotations for parameters and optional annotations for return types.

Note

A quick refresher on terminology:

When you invoke a function in TypeScript, you don’t need to provide any additional type information—just pass in some arguments, and TypeScript will go to work checking that your arguments are compatible with the types of your function’s parameters:

add(1,2)// evaluates to 3greet('Crystal')// evaluates to 'hello Crystal'

Of course, if you forgot an argument, or passed an argument of the wrong type, TypeScript will be quick to point it out:

add(1)// Error TS2554: Expected 2 arguments, but got 1.add(1,'a')// Error TS2345: Argument of type '"a"' is not assignable// to parameter of type 'number'.

Optional and Default Parameters

Like in object and tuple types, you can use ? to mark parameters as optional. When declaring your function’s parameters, required parameters have to come first, followed by optional parameters:

functionlog(message:string,userId?:string){lettime=newDate().toLocaleTimeString()console.log(time,message,userId||'Not signed in')}log('Page loaded')// Logs "12:38:31 PM Page loaded Not signed in"log('User signed in','da763be')// Logs "12:38:31 PM User signed in da763be"

Like in JavaScript, you can provide default values for optional parameters. Semantically it’s similar to making a parameter optional, in that callers no longer have to pass it in (a difference is that default parameters don’t have to be at the end of your list of parameters, while optional parameters do).

For example, we can rewrite log as:

functionlog(message:string,userId='Not signed in'){lettime=newDate().toISOString()console.log(time,message,userId)}log('User clicked on a button','da763be')log('User signed out')

Notice how when we give userId a default value, we remove its optional annotation, ?. We also don’t have to type it anymore. TypeScript is smart enough to infer the parameter’s type from its default value, keeping our code terse and easy to read.

Of course, you can also add explicit type annotations to your default parameters, the same way you can for parameters without defaults:

typeContext={appId?:stringuserId?:string}functionlog(message:string,context:Context={}){lettime=newDate().toISOString()console.log(time,message,context.userId)}

You’ll find yourself using default parameters over optional parameters often.

Rest Parameters

If a function takes a list of arguments, you can of course simply pass the list in as an array:

functionsum(numbers:number[]):number{returnnumbers.reduce((total,n)=>total+n,0)}sum([1,2,3])// evaluates to 6

Sometimes, you might opt for a variadic function API—one that takes a variable number of arguments—instead of a fixed-arity API that takes a fixed number of arguments. Traditionally, that required using JavaScript’s magic arguments object.

arguments is “magic” because your JavaScript runtime automatically defines it for you in functions, and assigns to it the list of arguments you passed to your function. Because arguments is only array-like, and not a true array, you first have to convert it to an array before you can call the built-in .reduce on it:

functionsumVariadic():number{returnArray.from(arguments).reduce((total,n)=>total+n,0)}sumVariadic(1,2,3)// evaluates to 6

But there’s one big problem with using arguments: it’s totally unsafe! If you hover over total or n in your text editor, you’ll see output similar to that shown in Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1. arguments is unsafe

This means TypeScript inferred that both n and total are of type any, and silently let it pass—that is, until you try to use sumVariadic:

sumVariadic(1,2,3)// Error TS2554: Expected 0 arguments, but got 3.

Since we didn’t declare that sumVariadic takes arguments, from TypeScript’s point of view it doesn’t take any arguments, so we get a TypeError when we try to use it.

So, how can we safely type variadic functions?

Rest parameters to the rescue! Instead of resorting to the unsafe arguments magic variable, we can instead use rest parameters to safely make our sum function accept any number of arguments:

functionsumVariadicSafe(...numbers:number[]):number{returnnumbers.reduce((total,n)=>total+n,0)}sumVariadicSafe(1,2,3)// evaluates to 6

That’s it! Notice that the only change between this variadic sum and our original single-parameter sum function is the extra ... in the parameter list—nothing else has to change, and it’s totally typesafe.

A function can have at most one rest parameter, and that parameter has to be the last one in the function’s parameter list. For example, take a look at TypeScript’s built-in declaration for console.log (if you don’t know what an interface is, don’t worry—we’ll cover it in Chapter 5). console.log takes an optional message, and any number of additional arguments to log:

interfaceConsole{log(message?:any,...optionalParams:any[]):void}

call, apply, and bind

In addition to invoking a function with parentheses (), JavaScript supports at least two other ways to call a function. Take add from earlier in the chapter:

functionadd(a:number,b:number):number{returna+b}add(10,20)// evaluates to 30add.apply(null,[10,20])// evaluates to 30add.call(null,10,20)// evaluates to 30add.bind(null,10,20)()// evaluates to 30

apply binds a value to this within your function (in this example, we bind this to null), and spreads its second argument over your function’s parameters. call does the same, but applies its arguments in order instead of spreading.

bind() is similar, in that it binds a this-argument and a list of arguments to your function. The difference is that bind does not invoke your function; instead, it returns a new function that you can then invoke with (), .call, or .apply, passing more arguments in to be bound to the so far unbound parameters if you want.

Typing this

If you’re not coming from JavaScript, you may be surprised to learn that in JavaScript the this variable is defined for every function, not just for those functions that live as methods on classes. this has a different value depending on how you called your function, which can make it notoriously fragile and hard to reason about.

Tip

For this reason, a lot of teams ban this everywhere except in class methods—to do this for your codebase too, enable the no-invalid-this TSLint rule.

The reason that this is fragile has to do with the way it’s assigned. The general rule is that this will take the value of the thing to the left of the dot when invoking a method. For example:

letx={a() {returnthis}}x.a()// this is the object x in the body of a()

But if at some point you reassign a before calling it, the result will change!

leta=x.aa()// now, this is undefined in the body of a()

Say you have a utility function for formatting dates that looks like this:

functionfancyDate() {return${this.getDate()}/${this.getMonth()}/${this.getFullYear()}}

You designed this API in your early days as a programmer (before you learned about function parameters). To use fancyDate, you have to call it with a Date bound to this:

fancyDate.call(newDate)// evaluates to "4/14/2005"

If you forget to bind a Date to this, you’ll get a runtime exception!

fancyDate()// Uncaught TypeError: this.getDate is not a function

Though exploring all of the semantics of this is beyond the scope of this book,2 this behavior—that this depends on the way you called a function, and not on the way that you declared it—can be surprising to say the least.

Thankfully, TypeScript has your back. If your function uses this, be sure to declare your expected this type as your function’s first parameter (before any additional parameters), and TypeScript will enforce that this really is what you say it is at every call site. this isn’t treated like other parameters—it’s a reserved word when used as part of a function signature:

functionfancyDate(this:Date){return${this.getDate()}/${this.getMonth()}/${this.getFullYear()}}

Now here’s what happens when we call fancyDate:

fancyDate.call(newDate)// evaluates to "6/13/2008"fancyDate()// Error TS2684: The 'this' context of type 'void' is// not assignable to method's 'this' of type 'Date'.

We took a runtime error, and gave TypeScript enough information to warn about the error at compile time instead.

TSC Flag: noImplicitThis

To enforce that this types are always explicitly annotated in functions, enable the noImplicitThis setting in your tsconfig.json. strict mode includes noImplicitThis, so if you already have that enabled you’re good to go.

Note that noImplicitThis doesn’t enforce this-annotations for classes, or for functions on objects.

Generator Functions

Generator functions (generators for short) are a convenient way to, well, generate a bunch of values. They give the generator’s consumer fine control over the pace at which values are produced. Because they’re lazy—that is, they only compute the next value when a consumer asks for it—they can do things that can be hard to do otherwise, like generate infinite lists.

They work like this:

function*createFibonacciGenerator() {leta=0letb=1while(true){yielda;[a,b]=[b,a+b]}}letfibonacciGenerator=createFibonacciGenerator()// IterableIterator<number>fibonacciGenerator.next()// evaluates to {value: 0, done: false}fibonacciGenerator.next()// evaluates to {value: 1, done: false}fibonacciGenerator.next()// evaluates to {value: 1, done: false}fibonacciGenerator.next()// evaluates to {value: 2, done: false}fibonacciGenerator.next()// evaluates to {value: 3, done: false}fibonacciGenerator.next()// evaluates to {value: 5, done: false}

The asterisk (

*) before a function’s name makes that function a generator. Calling a generator returns an iterable iterator.

Our generator can generate values forever.

Generators use the

yieldkeyword to, well, yield values. When a consumer asks for the generator’s next value (for example, by callingnext),yieldsends a result back to the consumer and pauses execution until the consumer asks for the next value. In this way thewhile(true)loop doesn’t immediately cause the program to run forever and crash.

To compute the next Fibonacci number, we reassign

atobandbtoa + bin a single step.

We called createFibonacciGenerator, and that returned an IterableIterator. Every time we call next, the iterator computes the next Fibonacci number and yields it back to us. Notice how TypeScript is able to infer the type of our iterator from the type of the value we yielded.

You can also explicitly annotate a generator, wrapping the type it yields in an IterableIterator:

function*createNumbers():IterableIterator<number>{letn=0while(1){yieldn++}}letnumbers=createNumbers()numbers.next()// evaluates to {value: 0, done: false}numbers.next()// evaluates to {value: 1, done: false}numbers.next()// evaluates to {value: 2, done: false}

We won’t delve deeper into generators in this book—they’re a big topic, and since this book is about TypeScript, I don’t want to get sidetracked with JavaScript features. The short of it is they’re a super cool JavaScript language feature that TypeScript supports too. To learn more about generators, head to their page on MDN.

Iterators

Iterators are the flip side to generators: while generators are a way to produce a stream of values, iterators are a way to consume those values. The terminology can get pretty confusing, so let’s start with a couple of definitions.

When you create a generator (say, by calling createFibonacciGenerator), you get a value back that’s both an iterable and an iterator—an iterable iterator—because it defines both a Symbol.iterator property and a next method.

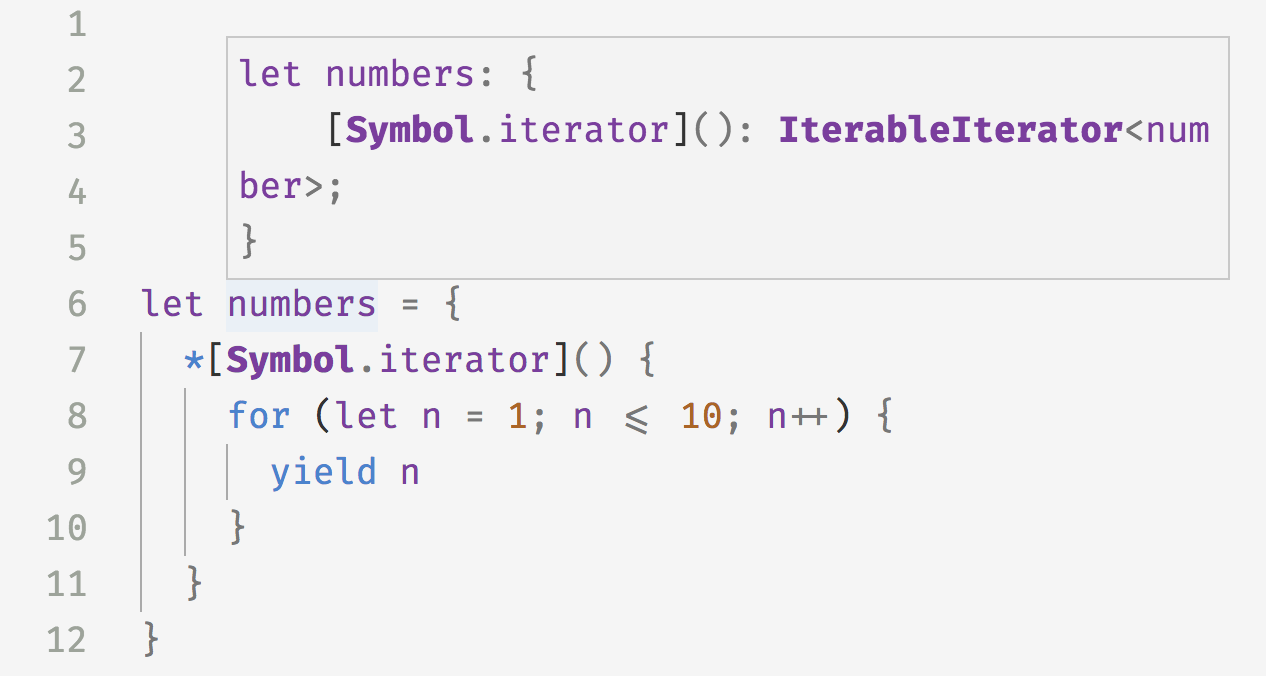

You can manually define an iterator or an iterable by creating an object (or a class) that implements Symbol.iterator or next, respectively. For example, let’s define an iterator that returns the numbers 1 through 10:

letnumbers={*[Symbol.iterator](){for(letn=1;n<=10;n++){yieldn}}}

If you type that iterator into your code editor and hover over it, you’ll see what TypeScript infers as its type (Figure 4-2).

Figure 4-2. Manually defining an iterator

In other words, numbers is an iterator, and calling the generator function numbers[Symbol.iterator]() returns an iterable iterator.

Not only can you define your own iterators, but you can use JavaScript’s built-in iterators for common collection types—Array, Map, Set, String,3 and so on—to do things like:

// Iterate over an iterator with for-offor(letaofnumbers){// 1, 2, 3, etc.}// Spread an iteratorletallNumbers=[...numbers]// number[]// Destructure an iteratorlet[one,two,...rest]=numbers// [number, number, number[]]

Again, we won’t go more deeply into iterators in this book. You can read more about iterators and async iterators on MDN.

TSC Flag: downlevelIteration

If you’re compiling your TypeScript to a JavaScript version older than ES2015, you can enable custom iterators with the downlevelIteration flag in your tsconfig.json.

You may want to keep downlevelIteration disabled if your application is especially sensitive to bundle size: it takes a lot of code to get custom iterators working in older environments. For example, the previous numbers example generates nearly 1 KB of code (gzipped).

Call Signatures

So far, we’ve learned to type functions’ parameters and return types. Now, let’s switch gears and talk about how we can express the full types of functions themselves.

Let’s revisit sum from the top of this chapter. As a reminder, it looks like this:

functionsum(a:number,b:number):number{returna+b}

What is the type of sum? Well, sum is a function, so its type is:

FunctionThe Function type, as you may have guessed, is not what you want to use most of the time. Like object describes all objects, Function is a catchall type for all functions, and doesn’t tell you anything about the specific function that it types.

How else can we type sum? sum is a function that takes two numbers and returns a number. In TypeScript we can express its type as:

(a:number,b:number)=>number

This is TypeScript’s syntax for a function’s type, or call signature (also called a type signature). You’ll notice it looks remarkably similar to an arrow function—this is intentional! When you pass functions around as arguments, or return them from other functions, this is the syntax you’ll use to type them.

Note

The parameter names a and b just serve as documentation, and don’t affect the assignability of a function with that type.

Function call signatures only contain type-level code—that is, types only, no values. That means function call signatures can express parameter types, this types (see “Typing this”), return types, rest types, and optional types, and they cannot express default values (since a default value is a value, not a type). And because they have no body for TypeScript to infer from, call signatures require explicit return type annotations.

Let’s go through a few of the examples of functions we’ve seen so far in this chapter, and pull out their types into standalone call signatures that we’ll bind to type aliases:

// function greet(name: string)typeGreet=(name:string)=>string// function log(message: string, userId?: string)typeLog=(message:string,userId?:string)=>void// function sumVariadicSafe(...numbers: number[]): numbertypeSumVariadicSafe=(...numbers:number[])=>number

Getting the hang of it? The functions’ call signatures look remarkably similar to their implementations. This is intentional, and is a language design choice that makes call signatures easier to reason about.

Let’s make the relationship between call signatures and their implementations more concrete. If you have a call signature, how can you declare a function that implements that signature? You simply combine the call signature with a function expression that implements it. For example, let’s rewrite Log to use its shiny new signature:

typeLog=(message:string,userId?:string)=>voidletlog:Log=(message,userId='Not signed in')=>{lettime=newDate().toISOString()console.log(time,message,userId)}

We declare a function expression

log, and explicitly type it as typeLog.

We don’t need to annotate our parameters twice. Since

messageis already annotated as astringas part of the definition forLog, we don’t need to type it again here. Instead, we let TypeScript infer it for us fromLog.

We add a default value for

userId, since we captureduserId’s type in our signature forLog, but we couldn’t capture the default value as part ofLogbecauseLogis a type and can’t contain values.

We don’t need to annotate our return type again, since we already declared it as

voidin ourLogtype.

Contextual Typing

Notice that the last example was the first example we’ve seen where we didn’t have to explicitly annotate our function parameter types. Because we already declared that log is of type Log, TypeScript is able to infer from context that message has to be of type string. This is a powerful feature of TypeScript’s type inference called contextual typing.

Earlier in this chapter, we touched on one other place where contextual typing comes up: callback functions.5

Let’s declare a function times that calls its callback f some number of times n, passing the current index to f each time:

functiontimes(f:(index:number)=>void,n:number){for(leti=0;i<n;i++){f(i)}}

When you call times, you don’t have to explicitly annotate the function you pass to times if you declare that function inline:

times(n=>console.log(n),4)

TypeScript infers from context that n is a number—we declared that f’s argument index is a number in times’s signature, and TypeScript is smart enough to infer that n is that argument, so it must be a number.

Note that if we didn’t declare f inline, TypeScript wouldn’t have been able to infer its type:

functionf(n){// Error TS7006: Parameter 'n' implicitly has an 'any' type.console.log(n)}times(f,4)

Overloaded Function Types

The function type syntax we used in the last section—type Fn = (...) => ...—is a shorthand call signature. We can instead write it out more explicitly. Again taking the example of Log:

// Shorthand call signaturetypeLog=(message:string,userId?:string)=>void// Full call signaturetypeLog={(message:string,userId?:string):void}

The two are completely equivalent in every way, and differ only in syntax.

Would you ever want to use a full call signature over the shorthand? For simple cases like our Log function, you should prefer the shorthand; but for more complicated functions, there are a few good use cases for full signatures.

The first of these is overloading a function type. But first, what does it even mean to overload a function?

In most programming languages, once you declare a function that takes some set of parameters and yields some return type, you can call that function with exactly that set of parameters, and you will always get that same return type back. Not so in JavaScript. Because JavaScript is such a dynamic language, it’s a common pattern for there to be multiple ways to call a given function; not only that, but sometimes the output type will actually depend on the input type for an argument!

TypeScript models this dynamism—overloaded function declarations, and a function’s output type depending on its input type—with its static type system. We might take this language feature for granted, but it’s a really advanced feature for a type system to have!

You can use overloaded function signatures to design really expressive APIs. For example, let’s design an API to book a vacation—we’ll call it Reserve. Let’s start by sketching out its types (with a full type signature this time):

typeReserve={(from:Date,to:Date,destination:string):Reservation}

Let’s then stub out an implementation for Reserve:

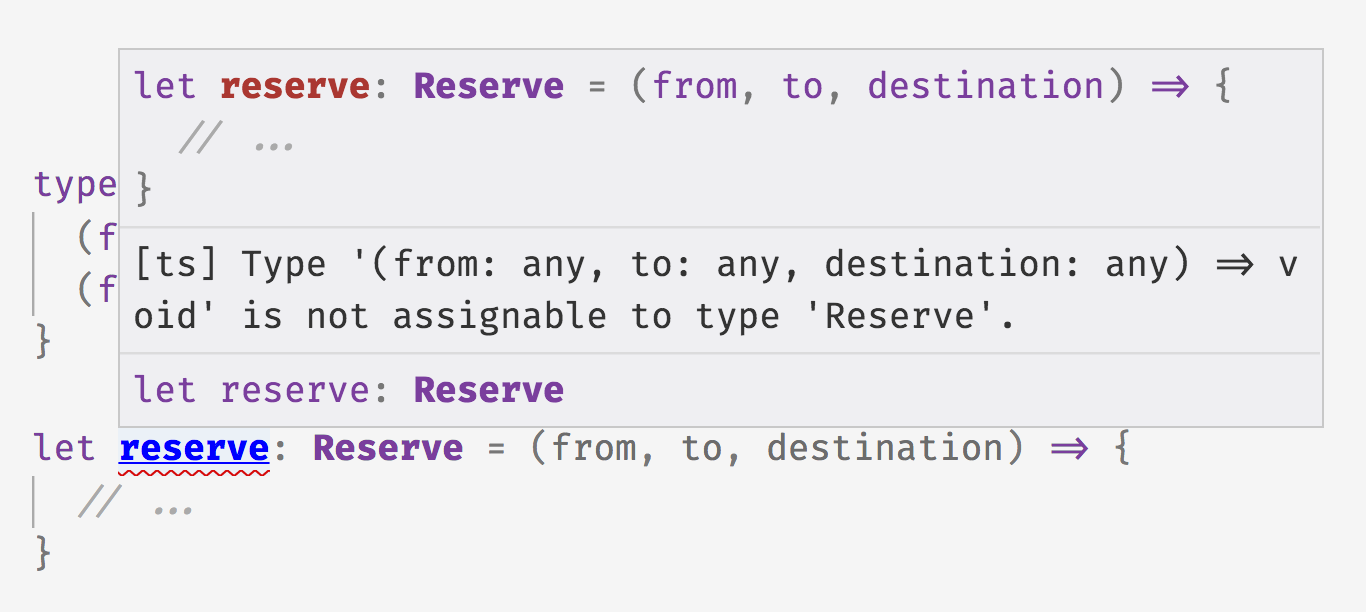

letreserve:Reserve=(from,to,destination)=>{// ...}

So a user who wants to book a trip to Bali has to call our reserve API with a from date, a to date, and "Bali" as a destination.

We might repurpose our API to support one-way trips too:

typeReserve={(from:Date,to:Date,destination:string):Reservation(from:Date,destination:string):Reservation}

You’ll notice that when you try to run this code, TypeScript will give you an error at the point where you implement Reserve (see Figure 4-3).

Figure 4-3. TypeError when missing a combined overload signature

This is because of the way call signature overloading works in TypeScript. If you declare a set of overload signatures for a function f, from a caller’s point of view f’s type is the union of those overload signatures. But from f’s implementation’s point of view, there needs to be a single, combined type that can actually be implemented. You need to manually declare this combined call signature when implementing f—it won’t be inferred for you. For our Reserve example, we can update our reserve function like this:

typeReserve={(from:Date,to:Date,destination:string):Reservation(from:Date,destination:string):Reservation}letreserve:Reserve=(from:Date,toOrDestination:Date|string,destination?:string)=>{// ...}

We declare two overloaded function signatures.

The implementation’s signature is the result of us manually combining the two overload signatures (in other words, we computed

Signature1 | Signature2by hand). Note that the combined signature isn’t visible to functions that callreserve; from a consumer’s point of view,Reserve’s signature is:typeReserve={(from:Date,to:Date,destination:string):Reservation(from:Date,destination:string):Reservation}Notably, this doesn’t include the combined signature we created:

// Wrong!typeReserve={(from:Date,to:Date,destination:string):Reservation(from:Date,destination:string):Reservation(from:Date,toOrDestination:Date|string,destination?:string):Reservation}

Since reserve might be called in either of two ways, when you implement reserve you have to prove to TypeScript that you checked how it was called:6

letreserve:Reserve=(from:Date,toOrDestination:Date|string,destination?:string)=>{if(toOrDestinationinstanceofDate&&destination!==undefined){// Book a one-way trip}elseif(typeoftoOrDestination==='string'){// Book a round trip}}

Overloads come up naturally in browser DOM APIs. The createElement DOM API, for example, is used to create a new HTML element. It takes a string corresponding to an HTML tag and returns a new HTML element of that tag’s type. TypeScript comes with built-in types for each HTML element. These include:

-

HTMLAnchorElementfor<a>elements -

HTMLCanvasElementfor<canvas>elements -

HTMLTableElementfor<table>elements

Overloaded call signatures are a natural way to model how createElement works. Think about how you might type createElement (try to answer this by yourself before you read on!).

The answer:

typeCreateElement={(tag:'a'):HTMLAnchorElement(tag:'canvas'):HTMLCanvasElement(tag:'table'):HTMLTableElement(tag:string):HTMLElement}letcreateElement:CreateElement=(tag:string):HTMLElement=>{// ...}

We overload on the parameter’s type, matching on it with string literal types.

We add a catchall case: if the user passed a custom tag name, or a cutting-edge experimental tag name that hasn’t made its way into TypeScript’s built-in type declarations yet, we return a generic

HTMLElement. Since TypeScript resolves overloads in the order they were declared,7 when you callcreateElementwith a string that doesn’t have a specific overload defined (e.g.,createElement('foo')), TypeScript will fall back toHTMLElement.

To type the implementation’s parameter, we combine all the types that parameter might have in

createElement’s overload signatures, resulting in'a' | 'canvas' | 'table' | string. Since the three string literal types are all subtypes ofstring, the type reduces to juststring.

Note

In all of the examples in this section we overloaded function expressions. But what if we want to overload a function declaration? As always, TypeScript has your back, with an equivalent syntax for function declarations. Let’s rewrite our createElement overloads:

functioncreateElement(tag:'a'):HTMLAnchorElementfunctioncreateElement(tag:'canvas'):HTMLCanvasElementfunctioncreateElement(tag:'table'):HTMLTableElementfunctioncreateElement(tag:string):HTMLElement{// ...}

Which syntax you use is up to you, and depends on what kind of function you’re overloading (function expression or function declarations).

Full type signatures aren’t limited to overloading how you call a function. You can also use them to model properties on functions. Since JavaScript functions are just callable objects, you can assign properties to them to do things like:

functionwarnUser(warning){if(warnUser.wasCalled){return}warnUser.wasCalled=truealert(warning)}warnUser.wasCalled=false

That is, we show the user a warning, and we don’t show a warning more than once. Let’s use TypeScript to type warnUser’s full signature:

typeWarnUser={(warning:string):voidwasCalled:boolean}

We can then rewrite warnUser as a function expression that implements that signature:

letwarnUser:WarnUser=(warning:string)=>{if(warnUser.wasCalled){return}warnUser.wasCalled=truealert(warning)}warnUser.wasCalled=false

Note that TypeScript is smart enough to realize that though we didn’t assign wasCalled to warnUser when we declared the warnUser function, we did assign wasCalled to it right after.

Polymorphism

So far in this book, we’ve been talking about the hows and whys of concrete types, and functions that use concrete types. What’s a concrete type? It so happens that every type we’ve seen so far is concrete:

-

boolean -

string -

Date[] -

{a: number} | {b: string} -

(numbers: number[]) => number

Concrete types are useful when you know precisely what type you’re expecting, and want to verify that type was actually passed. But sometimes, you don’t know what type to expect beforehand, and you don’t want to restrict your function’s behavior to a specific type!

As an example of what I mean, let’s implement filter. You use filter to iterate over an array and refine it; in JavaScript, it might look like this:

functionfilter(array,f){letresult=[]for(leti=0;i<array.length;i++){letitem=array[i]if(f(item)){result.push(item)}}returnresult}filter([1,2,3,4],_=>_<3)// evaluates to [1, 2]

Let’s start by pulling out filter’s full type signature, and adding some placeholder unknowns for the types:

typeFilter={(array:unknown,f:unknown)=>unknown[]}

Now, let’s try to fill in the types with, say, number:

typeFilter={(array:number[],f:(item:number)=>boolean):number[]}

Typing the array’s elements as number works well for this example, but filter is meant to be a generic function—you can filter arrays of numbers, strings, objects, other arrays, anything. The signature we wrote works for arrays of numbers, but it doesn’t work for arrays of other types of elements. Let’s try to use an overload to extend it to work on arrays of strings too:

typeFilter={(array:number[],f:(item:number)=>boolean):number[](array:string[],f:(item:string)=>boolean):string[]}

So far so good (though it might get messy to write out an overload for every type). What about arrays of objects?

typeFilter={(array:number[],f:(item:number)=>boolean):number[](array:string[],f:(item:string)=>boolean):string[](array:object[],f:(item:object)=>boolean):object[]}

This might look fine at first glance, but let’s try to use it to see where it breaks down. If you implement a filter function with that signature (that is, filter: Filter), and try to use it, you’ll get:

letnames=[{firstName:'beth'},{firstName:'caitlyn'},{firstName:'xin'}]letresult=filter(names,_=>_.firstName.startsWith('b'))// Error TS2339: Property 'firstName' does not exist on type 'object'.result[0].firstName// Error TS2339: Property 'firstName' does not exist// on type 'object'.

At this point, it should make sense why TypeScript is throwing this error. We told TypeScript that we might pass an array of numbers, strings, or objects to filter. We passed an array of objects, but remember that object doesn’t tell you anything about the shape of the object. So each time we try to access a property on an object in the array, TypeScript throws an error, because we didn’t tell it what specific shape the object has.

What to do?

If you come from a language that supports generic types, then by now you are rolling your eyes and shouting, “THAT’S WHAT GENERICS ARE FOR!” The good news is, you’re spot on (the bad news is, you just woke up the neighbors’ kid with your shouting).

In case you haven’t worked with generic types before, I’ll define them first, then give an example with our filter function.

Going back to our filter example, here is what its type looks like when we rewrite it with a generic type parameter T:

typeFilter={<T>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]}

What we’ve done here is say: “This function filter uses a generic type parameter T; we don’t know what this type will be ahead of time, so TypeScript if you can infer what it is each time we call filter that would be swell.” TypeScript infers T from the type we pass in for array. Once TypeScript infers what T is for a given call to filter, it substitutes that type in for every T it sees. T is like a placeholder type, to be filled in by the typechecker from context; it parameterizes Filter’s type, which is why we call it a generic type parameter.

Note

Because it’s such a mouthful to say “generic type parameter” every time, people often shorten it to just “generic type,” or simply “generic.” I’ll use the terms interchangeably throughout this book.

The funny-looking angle brackets, <>, are how you declare generic type parameters (think of them like the type keyword, but for generic types); where you place the angle brackets scopes the generics (there are just a few places you can put them), and TypeScript makes sure that within their scope, all instances of the generic type parameters are eventually bound to the same concrete types. Because of where the angle brackets are in this example, TypeScript will bind concrete types to our generic T when we call filter. And it will decide which concrete type to bind to T depending on what we called filter with. You can declare as many comma-separated generic type parameters as you want between a pair of angle brackets.

Note

T is just a type name, and we could have used any other name instead: A, Zebra, or l33t. By convention, people use uppercase single-letter names starting with the letter T and continuing to U, V, W, and so on depending on how many generics they need.

If you’re declaring a lot of generics in a row or are using them in a complicated way, consider deviating from this convention and using more descriptive names like Value or WidgetType instead.

Some people prefer to start at A instead of T. Different programming language communities prefer one or the other, depending on their heritage: functional language users prefer A, B, C, and so on because of their likeness to the Greek letters α, β, and γ that you might find in math proofs; object-oriented language users tend to use T for “Type.” TypeScript, though it supports both programming styles, uses the latter convention.

Like a function’s parameter gets re-bound every time you call that function, so each call to filter gets its own binding for T:

typeFilter={<T>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]}letfilter:Filter=(array,f)=>// ...// (a) T is bound to numberfilter([1,2,3],_=>_>2)// (b) T is bound to stringfilter(['a','b'],_=>_!=='b')// (c) T is bound to {firstName: string}letnames=[{firstName:'beth'},{firstName:'caitlyn'},{firstName:'xin'}]filter(names,_=>_.firstName.startsWith('b'))

TypeScript infers these generic bindings from the types of the arguments we passed in. Let’s walk through how TypeScript binds T for (a):

-

From the type signature for

filter, TypeScript knows thatarrayis an array of elements of some typeT. -

TypeScript notices that we passed in the array

[1, 2, 3], soTmust benumber. -

Wherever TypeScript sees a

T, it substitutes in thenumbertype. So the parameterf: (item: T) => booleanbecomesf: (item: number) => boolean, and the return typeT[]becomesnumber[]. -

TypeScript checks that the types all satisfy assignability, and that the function we passed in as

fis assignable to its freshly inferred signature.

Generics are a powerful way to say what your function does in a more general way than what concrete types allow. The way to think about generics is as constraints. Just like annotating a function parameter as n: number constrains the value of the parameter n to the type number, so using a generic T constrains the type of whatever type you bind to T to be the same type everywhere that T shows up.

Tip

Generic types can also be used in type aliases, classes, and interfaces—we’ll use them copiously throughout this book. I’ll introduce them in context as we cover more topics.

Use generics whenever you can. They will help keep your code general, reusable, and terse.

When Are Generics Bound?

The place where you declare a generic type doesn’t just scope the type, but also dictates when TypeScript will bind a concrete type to your generic. From the last example:

typeFilter={<T>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]}letfilter:Filter=(array,f)=>// ...

Because we declared <T> as part of a call signature (right before the signature’s opening parenthesis, (), TypeScript will bind a concrete type to T when we actually call a function of type Filter.

If we’d instead scoped T to the type alias Filter, TypeScript would have required us to bind a type explicitly when we used Filter:

typeFilter<T>={(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]}letfilter:Filter=(array,f)=>// Error TS2314: Generic type 'Filter'// ...// requires 1 type argument(s).typeOtherFilter=Filter// Error TS2314: Generic type 'Filter'// requires 1 type argument(s).letfilter:Filter<number>=(array,f)=>// ...typeStringFilter=Filter<string>letstringFilter:StringFilter=(array,f)=>// ...

Generally, TypeScript will bind concrete types to your generic when you use the generic: for functions, it’s when you call them; for classes, it’s when you instantiate them (more on that in “Polymorphism”); and for type aliases and interfaces (see “Interfaces”), it’s when you use or implement them.

Where Can You Declare Generics?

For each of TypeScript’s ways to declare a call signature, there’s a way to add a generic type to it:

typeFilter={<T>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]}letfilter:Filter=// ...typeFilter<T>={(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]}letfilter:Filter<number>=// ...typeFilter=<T>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean)=>T[]letfilter:Filter=// ...typeFilter<T>=(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean)=>T[]letfilter:Filter<string>=// ...functionfilter<T>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>boolean):T[]{// ...}

A full call signature, with

Tscoped to an individual signature. BecauseTis scoped to a single signature, TypeScript will bind theTin this signature to a concrete type when you call a function of typefilter. Each call tofilterwill get its own binding forT.

A full call signature, with

Tscoped to all of the signatures. BecauseTis declared as part ofFilter’s type (and not part of a specific signature’s type), TypeScript will bindTwhen you declare a function of typeFilter.

Like

, but a shorthand call signature instead of a full one.

, but a shorthand call signature instead of a full one.

Like

, but a shorthand call signature instead of a full one.

, but a shorthand call signature instead of a full one.

A named function call signature, with

Tscoped to the signature. TypeScript will bind a concrete type toTwhen you callfilter, and each call tofilterwill get its own binding forT.

As a second example, let’s write a map function. map is pretty similar to filter, but instead of removing items from an array, it transforms each item with a mapping function. We’ll start by sketching out the implementation:

functionmap(array:unknown[],f:(item:unknown)=>unknown):unknown[]{letresult=[]for(leti=0;i<array.length;i++){result[i]=f(array[i])}returnresult}

Before you go on, try to think through how you’d make map generic, replacing each unknown with some type. How many generics do you need? How do you declare your generics, and scope them to the map function? What should the types of array, f, and the return value be?

Ready? If you didn’t try to do it yourself first, I encourage you to give it a shot. You can do it. Really!

OK, no more nagging. Here’s the answer:

functionmap<T,U>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>U):U[]{letresult=[]for(leti=0;i<array.length;i++){result[i]=f(array[i])}returnresult}

We need exactly two generic types: T for the type of the array members going in, and U for the type of the array members going out. We pass in an array of Ts, and a mapping function that takes a T and maps it to a U. Finally, we return an array of Us.

Generic Type Inference

In most cases, TypeScript does a great job of inferring generic types for you. When you call the map function we wrote earlier, TypeScript infers that T is string and U is boolean:

functionmap<T,U>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>U):U[]{// ...}map(['a','b','c'],// An array of T_=>_==='a'// A function that returns a U)

You can, however, explicitly annotate your generics too. Explicit annotations for generics are all-or-nothing; either annotate every required generic type, or none of them:

map<string,boolean>(['a','b','c'],_=>_==='a')map<string>(// Error TS2558: Expected 2 type arguments, but got 1.['a','b','c'],_=>_==='a')

TypeScript will check that each inferred generic type is assignable to its corresponding explicitly bound generic; if it’s not assignable, you’ll get an error:

// OK, because boolean is assignable to boolean | stringmap<string,boolean|string>(['a','b','c'],_=>_==='a')map<string,number>(['a','b','c'],_=>_==='a'// Error TS2322: Type 'boolean' is not assignable)// to type 'number'.

Since TypeScript infers concrete types for your generics from the arguments you pass into your generic function, sometimes you’ll hit a case like this:

letpromise=newPromise(resolve=>resolve(45))promise.then(result=>// Inferred as {}result*4// Error TS2362: The left-hand side of an arithmetic operation must)// be of type 'any', 'number', 'bigint', or an enum type.

What gives? Why did TypeScript infer result to be {}? Because we didn’t give it enough information to work with—since TypeScript only uses the types of a generic function’s arguments to infer a generic’s type, it defaulted T to {}!

To fix this, we have to explicitly annotate Promises generic type parameter:

letpromise=newPromise<number>(resolve=>resolve(45))promise.then(result=>// numberresult*4)

Generic Type Aliases

We already touched on generic type aliases with our Filter example from earlier in the chapter. And if you recall the Array and ReadonlyArray types from the last chapter (see “Read-only arrays and tuples”), those are generic type aliases too! Let’s take a deeper dive into using generics in type aliases by working through a brief example.

Let’s define a MyEvent type that describes a DOM event, like a click or a mousedown:

typeMyEvent<T>={target:Ttype:string}

Note that this is the only valid place to declare a generic type in a type alias: right after the type alias’s name, before its assignment (=).

MyEvent’s target property points to the element the event happened on: a <button />, a <div />, and so on. For example, you might describe a button event like this:

typeButtonEvent=MyEvent<HTMLButtonElement>

When you use a generic type like MyEvent, you have to explicitly bind its type parameters when you use the type; they won’t be inferred for you:

letmyEvent:Event<HTMLButtonElement|null>={target:document.querySelector('#myButton'),type:'click'}

You can use MyEvent to build another type—say, TimedEvent. When the generic T in TimedEvent is bound, TypeScript will also bind it to MyEvent:

typeTimedEvent<T>={event:MyEvent<T>from:Dateto:Date}

You can use a generic type alias in a function’s signature, too. When TypeScript binds a type to T, it’ll also bind it to MyEvent for you:

functiontriggerEvent<T>(event:MyEvent<T>):void{// ...}triggerEvent({// T is Element | nulltarget:document.querySelector('#myButton'),type:'mouseover'})

Let’s walk through what’s happening here step by step:

-

We call

triggerEventwith an object. -

TypeScript sees that according to our function’s signature, the argument we passed has to have the type

MyEvent<T>. It also notices that we definedMyEvent<T>as{target: T, type: string}. -

TypeScript notices that the

targetfield of the object we passed isdocument.querySelector('#myButton'). That implies thatTmust be whatever typedocument.querySelector('#myButton')is:Element | null. SoTis now bound toElement | null. -

TypeScript goes through and replaces every occurrence of

TwithElement | null. -

TypeScript checks that all of our types satisfy assignability. They do, so our code typechecks.

Bounded Polymorphism

Note

In this section I’m going to use a binary tree as an example. If you haven’t worked with binary trees before, don’t worry. For our purposes, the basics are:

-

A binary tree is a kind of data structure.

-

A binary tree consists of nodes.

-

A node holds a value, and can point to up to two child nodes.

-

A node can be one of two types: a leaf node (meaning it has no children) or an inner node (meaning it has at least one child).

Sometimes, saying “this thing is of some generic type T and that thing has to have the same type T" just isn’t enough. Sometimes you also want to say “the type U should be at least T.” We call this putting an upper bound on U.

Why might we want to do this? Let’s say we’re implementing a binary tree, and have three types of nodes:

-

Regular

TreeNodes -

LeafNodes, which areTreeNodes that don’t have children -

InnerNodes, which areTreeNodes that do have children

Let’s start by declaring types for our nodes:

typeTreeNode={value:string}typeLeafNode=TreeNode&{isLeaf:true}typeInnerNode=TreeNode&{children:[TreeNode]|[TreeNode,TreeNode]}

What we’re saying is: a TreeNode is an object with a single property, value. The LeafNode type has all the properties TreeNode has, plus a property isLeaf that’s always true. InnerNode also has all of TreeNode’s properties, plus a children property that points to either one or two children.

Next, let’s write a mapNode function that takes a TreeNode and maps over its value, returning a new TreeNode. We want to come up with a mapNode function that we can use like this:

leta:TreeNode={value:'a'}letb:LeafNode={value:'b',isLeaf:true}letc:InnerNode={value:'c',children:[b]}leta1=mapNode(a,_=>_.toUpperCase())// TreeNodeletb1=mapNode(b,_=>_.toUpperCase())// LeafNodeletc1=mapNode(c,_=>_.toUpperCase())// InnerNode

Now pause, and think about how you might write a mapNode function that takes a subtype of TreeNode and returns that same subtype. Passing in a LeafNode should return a LeafNode, an InnerNode should return an InnerNode, and a TreeNode should return a TreeNode. Consider how you’d do this before you move on. Is it possible?

Here’s the answer:

functionmapNode<TextendsTreeNode>(node:T,f:(value:string)=>string):T{return{...node,value:f(node.value)}}

mapNodeis a function that defines a single generic type parameter,T.Thas an upper bound ofTreeNode. That is,Tcan be either aTreeNode, or a subtype ofTreeNode.

mapNodetakes two parameters, the first of which is anodeof typeT. Because in we said

we said node extends TreeNode, if we passed in something that’s not aTreeNode—say, an empty object{},null, or an array ofTreeNodes—that would be an instant red squiggly.nodehas to be either aTreeNodeor a subtype ofTreeNode.

mapNodereturns a value of typeT. Remember thatTmight be aTreeNode, or any subtype ofTreeNode.

Why did we have to declare T that way?

-

If we had typed

Tas justT(leaving offextends TreeNode), thenmapNodewould have thrown a compile-time error, because you can’t safely readnode.valueon an unboundednodeof typeT(what if a user passes in a number?). -

If we had left off the

Tentirely and declaredmapNodeas(node: TreeNode, f: (value: string) => string) => TreeNode, then we would have lost information after mapping a node:a1,b1, andc1would all just beTreeNodes.

By saying that T extends TreeNode, we get to preserve the input node’s specific type (TreeNode, LeafNode, or InnerNode), even after mapping it.

Bounded polymorphism with multiple constraints

In the last example, we put a single type constraint on T: T has to be at least a TreeNode. But what if you want multiple type constraints?

Just extend the intersection (&) of those constraints:

typeHasSides={numberOfSides:number}typeSidesHaveLength={sideLength:number}functionlogPerimeter<ShapeextendsHasSides&SidesHaveLength>(s:Shape):Shape{console.log(s.numberOfSides*s.sideLength)returns}typeSquare=HasSides&SidesHaveLengthletsquare:Square={numberOfSides:4,sideLength:3}logPerimeter(square)// Square, logs "12"

Using bounded polymorphism to model arity

Another place where you’ll find yourself using bounded polymorphism is to model variadic functions (functions that take any number of arguments). For example, let’s implement our own version of JavaScript’s built-in call function (as a reminder, call is a function that takes a function and a variable number of arguments, and applies those arguments to the function).8 We’ll define and use it like this, using unknown for the types we’ll fill in later:

functioncall(f:(...args:unknown[])=>unknown,...args:unknown[]):unknown{returnf(...args)}functionfill(length:number,value:string):string[]{returnArray.from({length},()=>value)}call(fill,10,'a')// evaluates to an array of 10 'a's

Now let’s fill in the unknowns. The constraints we want to express are:

-

fshould be a function that takes some set of argumentsT, and returns some typeR. We don’t know how many arguments it’ll have ahead of time. -

calltakesf, along with the same set of argumentsTthatfitself takes. Again, we don’t know exactly how many arguments to expect ahead of time. -

callreturns the same typeRthatfreturns.

We’ll need two type parameters: T, which is an array of arguments, and R, which is an arbitrary return value. Let’s fill in the types:

functioncall<Textendsunknown[],R>(f:(...args:T)=>R,...args:T):R{returnf(...args)}

How exactly does this work? Let’s walk through it step by step:

-

-

callis a variadic function (as a reminder, a variadic function is a function that accepts any number of arguments) that has two type parameters:TandR.Tis a subtype ofunknown[]; that is,Tis an array or tuple of any type. -

-

call’s first parameter is a functionf.fis also variadic, and its arguments share a type withargs: whatever typeargsis,farguments have the same exact type. -

-

In addition to a function

f,callhas a variable number of additional parameters...args.argsis a rest parameter—that is, a parameter that describes a variable number of arguments.args’s type isT, andThas to be an array type (in fact, if we forgot to say thatTextends an array type, TypeScript would throw a squiggly at us), so TypeScript will infer a tuple type forTbased on the specific arguments we passed in forargs. -

-

callreturns a value of typeR(Ris bound to whatever typefreturns).

Now when we call call, TypeScript will know exactly what the return type is, and it will complain when we pass the wrong number of arguments:

leta=call(fill,10,'a')// string[]letb=call(fill,10)// Error TS2554: Expected 3 arguments; got 2.letc=call(fill,10,'a','z')// Error TS2554: Expected 3 arguments; got 4.

We use a similar technique to take advantage of the way TypeScript infers tuple types for rest parameters to improve type inference for tuples in “Improving Type Inference for Tuples”.

Generic Type Defaults

Just like you can give function parameters default values, you can give generic type parameters default types. For example, let’s revisit the MyEvent type from “Generic Type Aliases”. As a reminder, we used the type to model DOM events, and it looks like this:

typeMyEvent<T>={target:Ttype:string}

To create a new event, we have to explicitly bind a generic type to MyEvent, representing the type of HTML element that the event was dispatched on:

letbuttonEvent:MyEvent<HTMLButtonElement>={target:myButton,type:string}

As a convenience for when we don’t know the specific element type that MyEvent will be bound to beforehand, we can add a default for MyEvent’s generic:

typeMyEvent<T=HTMLElement>={target:Ttype:string}

We can also use this opportunity to apply what we learned in the last few sections and add a bound to T, to make sure that T is an HTML element:

typeMyEvent<TextendsHTMLElement=HTMLElement>={target:Ttype:string}

Now, we can easily create an event that’s not specific to a particular HTML element type, and we don’t have to manually bind MyEvents T to HTMLElement when we create the event:

letmyEvent:MyEvent={target:myElement,type:string}

Note that like optional parameters in functions, generic types with defaults have to appear after generic types without defaults:

// GoodtypeMyEvent2<Typeextendsstring,TargetextendsHTMLElement=HTMLElement,>={target:Targettype:Type}// BadtypeMyEvent3<TargetextendsHTMLElement=HTMLElement,Typeextendsstring// Error TS2706: Required type parameters may>={// not follow optional type parameters.target:Targettype:Type}

Type-Driven Development

With a powerful type system comes great power. When you write in TypeScript, you will often find yourself “leading with the types.” This, of course, refers to type-driven development.

The point of static type systems is to constrain the types of values an expression can hold. The more expressive the type system, the more it tells you about the value contained in that expression. When you apply an expressive type system to a function, the function’s type signature might end up telling you most of what you need to know about that function.

Let’s look at the type signature for the map function from earlier in this chapter:

functionmap<T,U>(array:T[],f:(item:T)=>U):U[]{// ...}

Just looking at that signature—even if you’ve never seen map before—you should have some intuition for what map does: it takes an array of T and a function that maps from a T to a U, and returns an array of U. Notice that you didn’t have to see the function’s implementation to know that!9

When you write a TypeScript program, start by defining your functions’ type signatures—in other words, lead with the types—filling in the implementations later. By sketching out your program out at the type level first, you make sure that everything makes sense at a high level before you get down to your implementations.

You’ll notice that so far, we’ve been doing the opposite: leading with the implementation, then deducing the types. Now that you have a grasp of writing and typing functions in TypeScript, we’re going to switch modes, sketching out the types first, and filling in the details later.

Summary

In this chapter we talked about how to declare and call functions, how to type parameters, and how to express common JavaScript function features like default parameters, rest parameters, generator functions, and iterators in TypeScript. We talked about the difference between functions’ call signatures and implementations, contextual typing, and the different ways to overload functions. Finally, we covered polymorphism for functions and type aliases in depth: why it’s useful, how and where to declare generic types, how TypeScript infers generic types, and how to declare and add bounds and defaults to your generics. We finished off with a short note on type-driven development: what it is, and how you can use your newfound knowledge of function types to do it.

Exercises

-

Which parts of a function’s type signature does TypeScript infer: the parameters, the return type, or both?

-

Is JavaScript’s

argumentsobject typesafe? If not, what can you use instead? -

You want the ability to book a vacation that starts immediately. Update the overloaded

reservefunction from earlier in this chapter (“Overloaded Function Types”) with a third call signature that takes just a destination, without an explicit start date. Updatereserve’s implementation to support this new overloaded signature. -

[Hard] Update our

callimplementation from earlier in the chapter (“Using bounded polymorphism to model arity”) to only work for functions whose second argument is astring. For all other functions, your implementation should fail at compile time. -

Implement a small typesafe assertion library,

is. Start by sketching out your types. When you’re done, you should be able to use it like this:

// Compare a string and a stringis('string','otherstring')// false// Compare a boolean and a booleanis(true,false)// false// Compare a number and a numberis(42,42)// true// Comparing two different types should give a compile-time erroris(10,'foo')// Error TS2345: Argument of type '"foo"' is not assignable// to parameter of type 'number'.// [Hard] I should be able to pass any number of argumentsis([1],[1,2],[1,2,3])// false

1 Why are they unsafe? If you enter that last example into your code editor, you’ll see that its type is Function. What is this Function type? It’s an object that is callable (you know, by putting () after it) and has all the prototype methods from Function.prototype. But its parameters and return type are untyped, so you can call the function with any arguments you want, and TypeScript will stand idly by, watching you do something that by all means should be illegal in whatever town you live in.

2 For a deep dive into this, check out Kyle Simpson’s You Don’t Know JS series from O’Reilly.

3 Notably, Object and Number are not iterators.

4 The exceptions to this rule of thumb are enums and namespaces. Enums generate both a type and a value, and namespaces exist just at the value level. See Appendix C for a complete reference.

5 If you haven’t heard the term “callback” before, all it is is a function that you passed as an argument to another function.

6 To learn more, jump ahead to “Refinement”.

7 Mostly—TypeScript hoists literal overloads above nonliteral ones, before resolving them in order. You might not want to depend on this feature, though, since it can make your overloads hard to understand for other engineers who aren’t familiar with this behavior.

8 To simplify our implementation a little, we’re going to design our call function to not take this into account.

9 There are a few programming languages (like the Haskell-like language Idris) that have built-in constraint solvers with the ability to automatically implement function bodies for you from the signatures you write!

Get Programming TypeScript now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.