Chapter 4. Specialized RDF Relationships: Reification, Containers, and Collections

Reification, collections, and containers deserve separate coverage from the rest of the RDF/XML syntax, primarily because these constructs have caused the most controversy and confusion. And most of this has to do with meaning.

It isn’t precisely clear what is happening, for instance, when I use reification syntax within an RDF/XML document. Am I making a statement about a statement? Am I claiming a special truth for the statement? Or how about the use of a collection or container—is there an interpretation of the relationship of the items within the groups that extends beyond the fact that the items are grouped?

During the process of revamping the RDF specification, the

RDF Working Group at one time actually pushed for the removal of

containers because the semantics associated with them could be easily

emulated using rdf:type. There was also

less than general approbation for the concept of reification, which no one

seemed to be quite happy with. However, the group kept containers and

reification, as well as adding in collections, but with a caveat: no

additional semantics are attached to these constructs other than those

that carefully delimited within the RDF documentation. Any additional

interpretation would then be between the RDF toolmaker and the people who

built the RDF vocabularies and used the tools. However, even within this,

there is common acceptance of additional semantics, particularly as

semantics relate to containers; of that, one can almost be

guaranteed.

In this chapter, we’ll not only look more closely at the physical aspects of reification, collections, and containers, we’ll also look at what they “mean,” intended or otherwise.

Containers

As I was writing this book, the RDF Working Group issued a document titled “Refactoring RDF/XML Syntax” detailing modifications to the RDF Model and Syntax Specification. One of the major changes to the specification was a modification related to RDF containers, the subject of this section. However, since the recommended modifications were fairly extensive, they couldn’t be covered within a note.

I rewrote this section of the book only to have the Working Group somewhat reverse itself as to the legitimacy of containers—containers would be included in the RDF/XML syntax, but their meaning would be constrained.

To ensure a proper perspective of containers, the next section contains an overview of containers as they were modeled in the original specification; a section detailing the changes from the refactoring follows. Finally, at the end I summarize containers as they are understood in the newest release of the RDF Syntax Specification.

Containers as Covered Within the Initial Specification Release

Resource properties can occur singly or in groups. To this point, we’ve looked at recording only individual properties, but RDF needs to record multiply occurring properties.

The creators of the RDF syntax were aware of this and created the concept of RDF Containers specifically for handling multiple resources or for handling multiple literals (properties). Each of the several types of RDF Containers has different behaviors and constraints.

Warning

This section covers containers as implemented in the first release of the RDF Model and Syntax Specification. It’s included for historical perspective and as an aid in understanding previous implementations of containers.

The first container we’ll look at is rdf:Bag, containing unordered lists of

resources or literals, with duplicate data allowed. An example of a

Bag could be an inventory of photographs, whereby the sequence that

the photos are listed in isn’t relevant. Example 4-1 demonstrates an RDF

document using a Bag.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#" xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/"> <rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/contest.htm"> <pstcn:photos> <rdf:Bag> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/capo.jpg" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/baritea.jpg" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/cfluorite.jpg" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/ccinnibar.jpg" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/baryto.jpg" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/cbarite2a.jpg" /> </rdf:Bag> </pstcn:photos> </rdf:Description> </rdf:RDF>

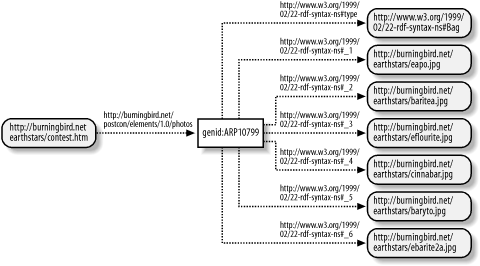

Figure 4-1 shows the RDF graph for this RDF/XML.

Within the RDF Validator, the elements of the Bag are also given

labels of _1, _2, and so on; automated processes identify

each individual element in the container with an automatically

generated number, preceded by an underscore ( _ ). In addition, the validator also

provides a unique identifier for the resource bubble representing the

Bag of the format genid:number,

where number is, again, an automatically

generated number representing the resource.

In the example, the listed items within the RDF container are

identified with an RDF rdf:li or list item

tag, similar in semantics to the HTML li tag. Each resource is identified with a

resource attribute. If the container contained literals instead of

resources as items, then the format used for each item would be

similar to the following:

<rdf:li>Barite Photo</rdf:li>

A second type of container is the sequence, or rdf:Seq. An rdf:Seq groups resources or literals, just

as a Bag does, but unlike with rdf:Bag, the ordering of the contained

elements is considered significant and is indicated by the ordering of

the rdf:_n membership

properties. As with rdf:Bag,

duplicate resources or literals are allowed.

If you’re grouping web pages within a menu on your main web

page, you’ll most likely want to group the pages in RDF in such a way

that the order of the grouping is maintained. Using rdf:Seq, automated procedures can pick up

the pages and add them to your menu as new resources are added. An

example of the RDF file to support this is shown in Example 4-2.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/contest.htm">

<pstcn:menu>

<rdf:Seq>

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/articles.htm" />

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/dynatech.htm" />

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/interact.htm" />

</rdf:Seq>

</pstcn:menu>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF> The last container type is the Alternative container,

rdf:Alt. This container variation

provides alternatives for a specific value. An excellent use for it is

a listing of expressions written in different languages, such as a

greeting or label for a user interface item. The application that

processes the RDF would then pick the alternative based on a locale

setting for the environment in which the application is

running.

The rdf:Alt syntax does not

differ from that of the rdf:Bag and

rdf:Seq, except for the element

name. However, there must be at least one item within an rdf:Alt container, to act as the default

value for the resource—the first member listed.

Earlier I mentioned that a resource identifier could be a URI or an identifier to a URI given elsewhere in the RDF document. The latter is particularly helpful when using RDF Containers, providing a way to associate information with the group of items. Example 4-3 demonstrates how this would work with the RDF shown in Example 4-2.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/contest.htm">

<pstcn:menu>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="#menuitems">

<pstcn:menu>Links to additional resources</pstcn:menu>

</rdf:Description>

</pstcn:menu>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Seq rdf:ID="menuitems">

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/articles.htm" />

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/dynatech.htm" />

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/interact.htm" />

</rdf:Seq>

</rdf:RDF>In the original container specification, the document refers to

the individual container items as referents. To

specifically associate a statement with each referent rather than with

the container as a whole, the rdf:aboutEach

attribute was to be used with the RDF Description, rather than

rdf:about:

<rdf:Description aboutEach="#menuitems">

When this type of statement is applied to container elements,

they’re then referred to as distributive

referents. Though not restricted specifically to the Bag

container within the RDF syntax, the aboutEach attribute is usually associated

with the Bag due to the unordered nature of the Bag’s items.

Another RDF attribute for Bag elements is rdf:aboutEachPrefix.

This is used to associate information about each resource within a

specific directory or web location. If used with Example 4-3, it would look like

this:

<rdf:Decription aboutEachPrefix="http://burningbird.net"> <pstcn:phototype>JPEG</pstcn:phototype> </rdf:Description>

Instead of using an RDF Container for groups of properties, you can repeat the property (the predicate), modifying the value assigned to the property (the object) with each:

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/articles/monsters3.htm">

<pstcn:Contains>Physical description of giant squids</pstcn:Contains>

<pstcn:Contains>Tale of the Legendary Kraken</pstcn:Contains>

</rdf:Description>Which you use depends on whether you want to refer to the collection of items as a singular unit or not. If you do, you would use the Container; otherwise, you would most likely use the repeated property, as the syntax is simpler.

This section contained a description of containers as implemented in the original RDF Model and Syntax document. This description changed dramatically during the re-examination of the RDF specification, as detailed next.

Containers as Typed Nodes

The RDF Working Group states the following:

On 29th June 2001, the WG decided that containers will match the typed node production in the grammar (production 6.13) and that the container-specific productions (productions 6.25 to 6.31) and any references to them be removed from the grammar. rdf:li elements will be translated to rdf:_nnn elements when they are found matching either a propertyElt (production 6.12) or a typedNode (production 6.13).

The RDF Working Group and people implementing RDF solutions had

two concerns about containers: first, that the functionality

represented with containers can be expressed with the typed node

production, leading to confusion about which representation should be

used to express a specific statement; second, that RDF applications

have to have special knowledge of containers in

order to interpret the rdf:li

elements—unlike other RDF elements, rdf:li elements get translated into numbered

elements with the format of _1,

_2, and so on.

To deal with both of these issues, the group released a document, “Refactoring RDF/XML Syntax” (at http://www.w3.org/TR/2001/WD-rdf-syntax-grammar-20010906/) that recommended the removal of all special container constructs; container-like behavior will be implemented with typed node productions instead.

At first glance, this looked to be a significant change, and I was concerned about its impact on my own RDF implementations as well as this book. However, the Working Group assured us that these changes are to the specification and not necessarily changes to the syntax represented by the specification.

As contradictory as this first sounds, closer examination of the changes does reflect that, though the specification is modified, the actual syntax remains the same. This can be proven by taking a closer look at containers and reinterpreting them as typed nodes: how would something such as the container RDF in Example 4-1 fit within this newly modified syntax?

In the original specification, rdf:li elements are

translated into sequentially numbered elements of the format

rdf:_n—rdf:_1, rdf:_2, and so on. Within the newly modified

specification, rdf:li elements are

still translated into numbered elements; however, you can also specify

the numbered elements directly yourself or mix elements, though the

results of such mixing may be unexpected. Example 4-4 shows a modification

of the RDF/XML shown in Example

4-2 that fits within the newly modified specification.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/contest.htm">

<pstcn:menu>

<rdf:Seq>

<rdf:_1 rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/articles.htm" />

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/dynatech.htm" />

<rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/interact.htm" />

</rdf:Seq>

</pstcn:menu>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>The use of the Seq container type is still allowed; however, rather than representing a specific container construct, it now represents a typed node. The following would provide the same results:

<pstcn:MyBag> <rdf:_1 rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/articles.htm" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/dynatech.htm" /> <rdf:li rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/interact.htm" /> </pstcn:MyBag>

Implicit with both the rdf:Seq and the custom element is a type

statement associated with the node automatically when the type

attribute isn’t provided.

When the RDF Validator parses Example 4-4, you might expect that

the numbering of the rdf:li nodes

would begin with rdf_2, following

from the value set for the first contained element, rdf:_1. This isn’t the result and won’t be

the result from the RDF triples associated with the test cases;

numbering begins with rdf:_1 for

each grouping and isn’t impacted by manual settings of the other

contained and grouped elements.

How does this fit the typed node syntax? Remembering that

associated with an element such as rdf:Seq is a type= URI

property assignment, the following steps map the EBNF of the typed

node production directly to the instance diagrammed in Example 4-4:

<rdf:Seq> is derived directly from '<' typeName propAttr* '>'

where typeName = QName and

QName = rdf:Seq

where propAttr is the implicit type=URI for Seq

<rdf:_1> is derived directly from propertyElt

where propertyElt = '<' propName idRefAttr '/>'

where propName = QName

QName = rdf:_1

where idRefAttr = resourceAttr

resourceAttr = ' resource="' URI-Reference '"'And so on for the other properties.

As you can see, the container instance does map directly to the typed node production, and there is no loss of functionality based on dropping the container-specific syntax. However, just when I was starting to become comfortable with replacing the Container with a typed node, the Working Group reversed itself and included support for Containers—with modifications and a whole lot of annotations about “meaning.”

Containers Today

Containers are included within the RDF/XML Syntax

Specification, but without some of the supporting attributes, such as

rdf:aboutEach and

rdf:aboutEachPrefix, which have

been removed from the syntax. The key to the current status of

Containers is this sentence within the specification (as it existed in

its Last Call state):

RDF has a set of container membership properties and corresponding property elements that are mostly used with instances of the

rdf:Seq,rdf:Bagandrdf:Altclasses which may be written as typed node elements.

The Container classes of rdf:Seq, rdf:Bag, and rdf:Alt are still in the documentation, with

an understanding that these may be replaced with typed node

productions. And this does impose an implication constraint on the

container classes—as typed node productions, no additional semantics

as to the application of containers can exist outside of what could be

implied with typed nodes.

From an application perspective, containers are a grouping of

related items, each of which can be given a unique list property,

represented by rdf:li within

RDF/XML, or more properly, rdf:_n, with the

value of n representing the

ordering within the container (if ordering is implied by the

container, such as rdf:Seq). Example 4-5 is a valid use of

containers, in this case an rdf:Seq

with its intended semantic assumptions of ordering of the members of

the container.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/earthstars/contest.htm">

<pstcn:menu>

<rdf:Seq>

<rdf:_1 rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/articles.htm" />

<rdf:_2 rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/dynatech.htm" />

<rdf:_3 rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/interact.htm" />

</rdf:Seq>

</pstcn:menu>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>The RDF/XML in Example

4-4 could be replaced with the RDF/XML in Example 4-5, and the meaning

associated with the construction would be the same; the resulting RDF

graph replaces all rdf:li items

with rdf:_

n items based on the position of the item

within the container, as shown in Figure 4-2. The rdf:li property is a construct of the

RDF/XML syntax only and not a part of the RDF graph (or associated RDF

data model).

Warning

Though rdf:li is used and

still documented within the RDF specifications, its use is

discouraged within RDF/XML documents.

There are intended but not formally described semantics

associated with rdf:Seq — that the

contained items are ordered and that the number of items in rdf:Bag is finite

and unordered and duplicates are allowed. There are also intended but

not formally described semantics with rdf:Alt that each

item is an option, with the first item being the default if no other

is specified. However, there is nothing within the RDF specification

that formally requires applications heed these intended semantics,

other than general consensus. In fact, the documented semantics

surrounding containers are quite vague, which, in my opinion, makes

the use of containers suspect. Because of this, I recommend caution

when using

containers.

Collections

Unlike a container, a collection is considered to be a

finite grouping of items, with a given terminator. Within RDF/XML, a

collection is defined through the use of rdf:parseType="Collection" and through listing

the collected resources within the other collection block.

The use of Collection within RDF/XML is fairly straightforward and

uncomplicated. Example 4-6

demonstrates how easy it is to gather together like items into one

collection, just through the use of the Collection rdf:parseType.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://dynamicearth.com/earthstars/contest.htm">

<pstcn:menu rdf:parseType="Collection">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/articles.htm" />

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/dynatech.htm" />

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/interact.htm" />

</pstcn:menu>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>The extraordinary thing about Collection is the resulting RDF

directed graph. One could be amazed at how the simple little addition of

an rdf:parseType="Collection" could

result in the rather complex model that’s generated. Figure 4-3 shows what would result

from this type of RDF/XML construct.

As the graph demonstrates, a collection is a list (with rdf:type of rdf:List), and each node on the list has an

associated predicate of type (List)

as well as the first value in the list, given by the predicate rdf:first. Additionally, there is a

relationship between the nodes, with an associated rdf:predicate of rdf:rest. The list is then terminated with a

node, whose value is rdf:nil.

Traversing a collection becomes a matter of finding the start and

then accessing the rdf:next predicate

for that node and finding the associated resource attached to it, which

then points to the value associated with it, and so on.

As complex as this structure is, though, there are still loopholes

in the semantics associated with it. For instance, one could have

multiple instances of rdf:first

within a document; however, it would require a deliberate act to create

this condition, which is unlikely to happen. Again, the RDF

specification enforces only some basic understanding about lists, such

as (as previously mentioned) each consists of a finite number of items

with a terminator (though the terminator itself could be left off).

Based on this, my recommendation is that you use the RDF collection as

sparingly as you would use the RDF Container—use only when no other

construct matches your specific needs, and use it specifically as the

specification intended it to be used. If you’re unsure about the intent,

then don’t use it.

Now that we’ve had a chance to look at the various grouping constructs of RDF—and to understand the associated dangers associated with them—it’s time to look at another RDF construct that’s caused even more controversy and confusion: reification.

Reification: The RDF Big Ugly

In our legal system, a statement about a statement is considered hearsay and isn’t admissible in a court of law. Within the Resource Description Framework (RDF), this is also true—the implied statement is considered hearsay and can’t be accepted as an assertion by itself. However, the outer statement is treated as an assertion.

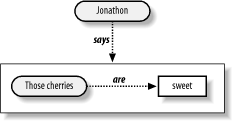

In a sentence such as “Jonathon says those cherries are sweet,” we’re really reading two statements. The first, inner statement is “Those cherries are sweet.” Since we haven’t tried the cherries directly, we can’t judge for ourselves whether this is true. But we do directly experience the outer statement, “Jonathon says...,” and we can judge this to be an assertion of fact. Graphically, this would look like the picture shown in Figure 4-4.

Now depending on our trust in Jonathon—that he tells the truth, that his interpretation of sweet is the same as ours—we can infer a trust for the inner statement, “those cherries are sweet,” based on our trust of the outer statement. If I run into Jonathon at a market and he says “Those cherries are sweet,” and I trust Jonathon and his judgment, I might be moved to purchase some of the cherries.

This same process of validating an inner statement based on trust of the outer—validation of hearsay—formed the basis of much of the earlier communication about the RDF construct called reification. And it is the implied trust that has created much of the push back against it, when there is no true implied trust with reification. With reification, a statement is modeled as a resource referenced by another statement. No more, no less.

Within the RDF semantics, a statement such as the following (from the specification), is easily documented with the RDF syntax provided in Chapter 3:

Ora Lassila is the creator of the resource http://www.w3.org/Home/Lassila.

In this statement, the RDF components of subject, predicate, and

object are clearly understood: the subject (resource) is http://www.w3.org/Home/Lassila, predicate is

creator, and object is Ora Lassila.

However, attach this statement as a statement being asserted by another person:

Ralph Swick says that Ora Lassila is the creator of the resource http://www.w3.org/Home/Lassila.

The syntax used in the examples in Chapter 3 doesn’t provide a mechanism to capture this type of assertion—this statement about another statement. However, capturing this type of information is exactly what’s needed when trying to assert that a statement about another statement is the fact being defined.

Statements such as “Ralph Swick says...” or “Jonathon says...” are termed metastatements; reification is a method of formally modeling a statement in such a way that it can actually be attached as a property to the new statement.

We’ll take a look at how reification is handled currently within the RDF specification. Later in the chapter, we’ll look at some of the discussions about reification, as well as uses of the concept.

Tip

A difficulty associated with reification and the current RDF specification documents is that nowhere in the documents, other than the grammar productions, is the RDF/XML associated with formal reification demonstrated.

Reified Statements

Occasionally I receive emails asking me to recommend web pages that contain tutorials, technical articles, and other helpful information. Instead of answering individual emails, my preference is to post a web page with links to resources that might be of interest to folks. For instance, I’m frequently asked about creating drop-down menus in Dynamic HTML (DHTML), and I’ll recommend the DHTML menu tutorials at WebReference.com, a very popular web site for the web developer:

http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus is a source containing tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus in DHTML.

Mapping this recommendation into RDF/XML, I would have something similar to the following:

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus/">

<pstcn:Contains>Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical

menus in DHTML</pstcn:Contains>

</rdf:Description>Now, this description is sufficient if all I want to do is describe the resource (the web page) and the context (provides tutorials and source code on creating DHTML hierarchical menus). But it’s missing one thing: an assertion about who is making the recommendation (me). Remove this RDF content from my web site, and you’ve lost the original context of the recommendation—the person making the recommendation. Within the RDF lexicon, we’re missing the statement about the statement.

To fill this gap, we need to associate the original statement to the new statement—the recommendation of the resource. To do this, we model the original statement so that it can be referenced as the subject of the newer statement. This forms the basis of reification in RDF. You can do this in a couple of different ways—using the long form or the short form of reification.

The long form of reification formally defines types— rdf:subject,

rdf:predicate, and rdf:object—and makes use of a fourth,

rdf:type, with a predefined value

of rdf:Statement. The three new

predicates capture the information about the inner statement, the

statement being reified if you will. rdf:type specifies that the resource is a

statement.

Tip

As discussed in Chapter

3, rdf:type isn’t limited

to use within reification.

At its simplest, the outer statement is attached as a statement directly to the reified statement. Example 4-7 contains an example of this type of reification.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/recommendation.htm">

<rdf:subject rdf:resource="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus" />

<rdf:predicate rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/schema/Contains" />

<rdf:object>Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus in DHTML</rdf:

object>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#Statement" />

<pstcn:recommendedBy>Shelley Powers</pstcn:recommendedBy>

</rdf:Description>

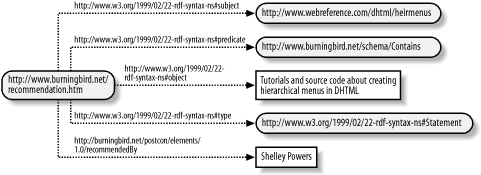

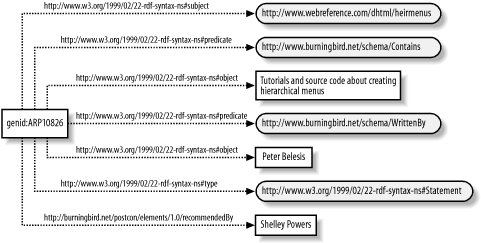

</rdf:RDF>In this document, graphically demonstrated in Figure 4-5, a statement is being

made about a resource: the resource at http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus

contains tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus

in DHTML. Who made the statement is given in the value of the pstcn:recommendedBy predicate: Shelley Powers. However, what we’re saying

is that this statement about the statement, the “Shelley Powers

recommends...” itself, is the assertion; we can’t determine the

truthfulness of the actual recommendation until we visit the site or

we take my statement as truth based on the trust placed in me.

Though this is valid RDF, it isn’t my preferred way of

demonstrating a clear-cut separation between the reified statement and

the assertion attached to that statement (demonstrating the inner and

outer statements). My preferred approach for reification is to

formally define a separate RDF resource for the outer statement and

then attach it to the reified statement. Example 4-8 demonstrates this. The

use of rdf:resource in the

outer statement connects the two statements.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/"

xml:base="http://burningbird.net/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="#s1">

<rdf:subject rdf:resource="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus" />

<rdf:predicate rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/schema/Contains" />

<rdf:object>Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus

in DHTML</rdf:object>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#Statement" />

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/person/001">

<pstcn:recommends rdf:resource="#s1" />

</rdf:Description>

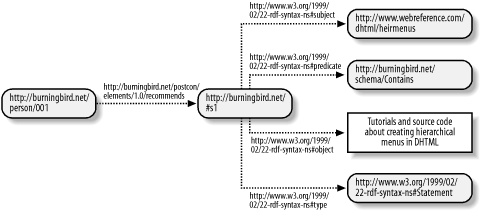

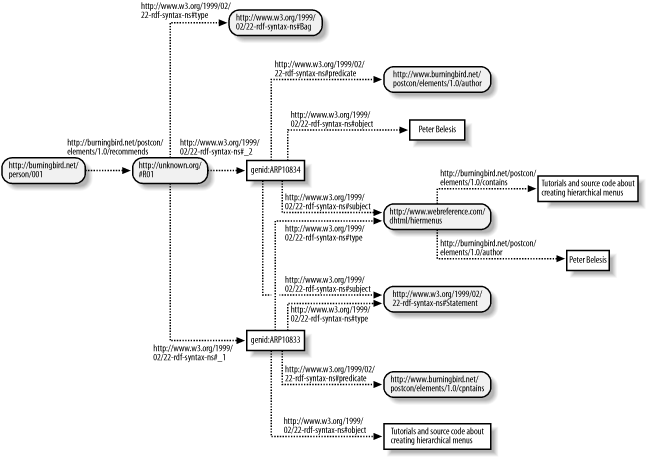

</rdf:RDF>In the example, the assertion about the reified statement is formally separated out. The RDF Validator-generated graphic of the RDF is shown in Figure 4-6.

In my opinion, this RDF results in a clearer and cleaner interpretation of the “statement about a statement.”

Warning

Some RDF Validators that incorporate RDF Schema validation would likely generate warnings for the RDF graph in Figure 4-6.

Having to repeat the subject, predicate, and object statements in every instance of reification is cumbersome, so there’s a short form you can use to achieve exactly the same RDF graph. And if the graphs agree, the RDF statements are guaranteed to agree.

The subject, predicate, and object of the reified statement are the familiar RDF trio, but the context of their use differs with reification. With reified statements, the subject, predicate, and object attributes are formal RDF elements that, combined, also happen to be a statement. These new components are used to model the statement.

A more detailed description of these new RDF elements is:

- subject

Contains the identifier for the resource referenced within the statement

- predicate

Contains the property that forms the original context of the resource (the property)

- object

Contains the value of the property that forms the original context of the resource (the value)

- type

Contains the type of the resource — in the example, the type of RDF statement

The formal representation of reification is based on N-Triples syntax. The reification from Examples Example 4-1 and Example 4-2 could be represented as:

{[X], type, [RDF:Statement]}

{[X], predicate, [contains]}

{[X], subject, [http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus]}

{[X], object, "Tutorial..."}This representation strips the statement to its essential components sans XML syntax.

It’s interesting that within the RDF Syntax Specification, the quad or 4-tuple representing a reified statement (subject, predicate, object, and type) is really a formalized model of our old friend, the RDF Description.

Consider for a moment that an RDF Description with at least one property is an RDF statement, containing subject, object, and predicate. This is represented by:

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus/">

<pstcn:Contains>Tuturials and source code about creating hierarchichal

menus in DHTML</pstcn:Contains>

</rdf:Description>However, let’s look at identifying this in “straight” XML as

follows, using a custom XML vocabulary called myrdf:

<myrdf:element>

<myrdf:subject>http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus/"</myrdf:subject>

<myrdf:predicate>Contains</myrdf:predicate>

<myrdf:object>Tutorials and source code about

creating hierarchical menus in DHTML</myrdf:object>

</myrdf:element>As you can see, this formal modeling of RDF Description is equivalent to the syntax used to model the reified statement given earlier. Following from this, then, you could say that all asserted statements within RDF (all statements given within RDF Description elements) are reified statements, and you would be correct—sort of.

The key to understanding reification within RDF is that a reified statement isn’t the statement itself, but the model of the statement. Reification isn’t the process of making a statement about another statement; it’s the process of formally modeling the statement.

From this example, you might be wondering why reification is necessary. After all, for this particular example, the recommendation could be attached directly as another statement about the web resource.

The Necessity of Reification and Metastatements

Why is reification necessary? One could model the example shown in Example 4-1 in serialized RDF syntax and not lose the information about who recommends the resource, as shown in Example 4-9.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/"

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus/">

<pstcn:Contains>Tuturials and source code about creating hierarchichal

menus in DHTML</pstcn:Contains>

<pstcn:recommendedBy>Shelley Powers</pstcn:recommendedBy>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>In this document, information about the person making the recommendation is attached as an additional statement about the original subject. At first glance, the new version of the RDF syntax used to describe the recommendation seems acceptable. However, using this interpretation, key information is lost—the statement about the resource is being treated as the fact, not the recommendation itself. With something such as the following:

Shelley Powers recommends http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus as a source of tutorials and source code for hierarchical menus created in DHTML.

the fact being described in the RDF document is “Shelley Powers recommends...,” not the actual web resource. The web resource is actually an ancillary component of the recommendation.

By being able to model the statement about the web resource, you can treat it as a property of another statement, and be able to distinguish without confusion and without ambiguity what “fact” you’re describing in an RDF statement. The importance of the distinction between the thing described (the web site) and the object making the description (the person making a recommendation of the web site) is both the key and the confusion of reification.

As handy as reification is, it is a bit wordy. The next section discusses a shorthand technique that can be used to reify several statements at a time.

A Shorthand Reification Syntax

Specifying the full predicate, subject, object, and type for each reified statement isn’t difficult, but it does get cumbersome after a while. Fortunately, there is a shorthand technique that you can use in place of the more formal syntax.

In Example 4-10,

rather than specifying each subject, predicate, object, and type, the

reified statement is identified through the rdf:ID property, and

the RDF parser automatically annotates the subject, predicate, object,

and type.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<!--The statement-->

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus">

<pstcn:Contains rdf:ID='s1'>

Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus in DHTML</pstcn:Contains>

</rdf:Description>

<!--The statement about the statement-->

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/person/001">

<pstcn:recommendedBy rdf:resource="#s1" />

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>Warning

This approach is cleaner to read and follow manually, and the graph is the same—almost. From an entailment point of view, though, these are the same, even though the model differs. Still, be forewarned on the use of this shortcut.

This shorthand technique is particularly helpful in circumstances other than just wanting a cleaner syntax. When you describe something, you usually don’t make just one statement about the thing you’re describing. For instance, if you’re recommending an article, you’ll usually give a description of the article, the name of the article, how to find a copy of the article, and so on.

In the recommendation example earlier, this original statement could be extended to provide the author of the web resource as well as the content:

Shelley Powers recommends http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus, written by Peter Belesis, as a source of tutorials and source code for hierarchical menus created in DHTML.

In this sentence, I’m recommending a web site that contains defined material and is authored by a specific individual.

The formal syntactic method of modeling this statement using the 4-tuple reification syntax doesn’t fit this particular data instance very well, because there’s confusion about exactly what I’m recommending—the web site or the author? There is no clean way to add in the additional statements.

To demonstrate my point, I modified the RDF/XML from Example 4-7 to add the additional statement related to the author. In this example, shown in Example 4-11, I interpreted the statement to break down into a couple of different assertions:

Shelley Powers recommends http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus as a source of tutorials and source code for hierarchical menus created in DHTML.

Shelley Powers recommends http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus, which is written by Peter Belesis.

I then modified the RDF/XML to reify both statements from the same subject.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description>

<rdf:subject rdf:resource="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus" />

<rdf:predicate rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/schema/Contains" />

<rdf:object>Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus

in DHTML</rdf:object>

<rdf:predicate rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/schema/WrittenBy" />

<rdf:object>Peter Belesis</rdf:object>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#Statement" />

<pstcn:recommendedBy>Shelley Powers</pstcn:recommendedBy>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>This RDF/XML in this document validates with the RDF Validator (at least, when this book was written), and the resultant graph shown in Figure 4-7 does represent what we want to say, in a way. However, our reaction to both the RDF/XML and the graph is “ugh.” I was surprised this would validate because there is an assumption, though not specifically mentioned in the RDF Syntax Specification, that a predicate, object, and type for a reified statement are attached to one subject, and one subject has only one predicate and object.

Happily, there’s a better approach to modeling this type of statement.

In RDF, statements about a specific subject can be included within the same description through the use of multiple predicates and objects associated with the subject. With the web resource example, the site contents and author are both facts about the resource and can be modeled as:

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus/">

<pstn:Contains>Tuturials and source code about creating hierarchichal

menus in DHTML</pstn:Contains>

<pstcn:writtenBy>Peter Belesis</pstcn:writtenBy>

</rdf:Description>Several statements can be included within one RDF Description

because there’s an implicit grouping associated with this element, an

rdf:Bag that acts as a container

for all statements about a specific resource. The concept of an

implicit description container also works with reified statements

through the introduction of a new RDF attribute, rdf:bagID. The

rdf:bagID attribute is used to

identify the implicit Bag defined with the RDF Description element

that groups multiple statements about a specific subject.

Note

During Last Call, the RDF Working Group decided that bagID was leading to confusion in tool

makers about the type of triples to generate. Since it’s use has

been limited, the WG removed rdf:bagID from the current RDF

specification. It’s inclusion in this book is for historical

perspective.

With the example about the web content, the rdf:bagId is used to wrap both statements

about the web site being recommended:

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus"

rdf:bagID="R01">

<pstcn:Contains> Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus

in DHTML</pstcn:Contains>

<pstcn:Author>Peter Belesis</pstcn:Author>

</rdf:Description>In this XML example, both statements being made—what the content

of the resource is and who authored it—are contained within an RDF

Description identified by the given rdf:bagID. With this approach, there is no

confusion that we have two statements being made about one resource

and that the higher-order recommendation is being made against the

resource, rather than any one individual statement about the

resource.

To complete the RDF document, all that’s left is to attach the higher-order statement. A complete XML document containing the new RDF is shown in Example 4-12.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.webreference.com/dhtml/hiermenus"

rdf:bagID="R01">

<pstcn:contains> Tutorials and source code about creating hierarchical menus

in DHTML</pstcn:contains>

<pstcn:author>Peter Belesis</pstcn:author>

</rdf:Description>

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/person/001">

<pstcn:recommendeds rdf:resource="#R01" />

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>The complete example, converted to a directed graph, is shown in Figure 4-8.

What Reification Solves

As we’ve seen in the examples earlier in the chapter, RDF reification is the only technique within RDF to model statements so that they can be grouped or attached as properties to another statement. In the examples, reified statements were used to capture information about a statement (a recommendation) made about another statement (a web resource).

In real-world situations, how would reification be used? What would it solve? Well, the key component of reification is the ability to make a statement and have the statement be treated as fact, without any implication that the contents of the statement are themselves facts. This has particular interest when it comes to trust.

Implying trust

In the earlier examples, we looked at modeling a recommendation for a web site using RDF and reification. The recommendation didn’t specifically address any level of trust—just the nature of the contents of the site and who wrote it. However, reification can be used to establish a level of trust.

As an example, 10 years ago if someone asked where you shopped for books, you might recommend a local neighborhood bookstore and say something along the lines of “they have a good selection,” or “Joe will let you browse all day without hassling you,” or even “the store cat’s a real sweetie.” You would then follow this person’s recommendation based on your own belief in that person’s judgment and honesty.

(During direct verification of the facts represented in the recommendation, if your hand gets shredded by the “sweet cat” when you try to pet it, you might modify your level of trust in the person’s judgment when it comes to animals.)

Nowadays when the “neighborhood” is several million kilometers of wire, providing recommendations to your neighbors is a bit more complicated. You can create web pages with reviews and attach links to stores, but this won’t provide useful information to automated agents that are out to do more than randomly collect links to stores. No, instead of just specifying a link to a store, you want to attach your views, your opinions, to the store.

Let’s say you shop at a bookstore called Some Bookstore. You like and trust this store so you provide a link to it at your web site. In addition, you also provide an RDF Description of the store, given in Example 4-13, for any RDF consumable agents that are looking for stores that can be trusted.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.somebookstore.com/">

<pstcn:webPurpose>online store</pstcn:webPurpose>

<pstcn:name>Some Bookstore</pstcn:name>

<pstcn:storeType>bookstore</pstcn:storeType>

<pstcn:trustLevel>High</pstcn:trustLevel>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>An agent would be able to not only collect the link for the store, it would also collect information about the store (the link belongs to an online bookstore that can be trusted—i.e., the trust level is high).

The agent would store the information about the link in its online storage, which is then used by a person searching for an online bookstore that can be trusted. The results of the search would display the following:

Some Bookstore, found at http://www.somebookstore.com/, is an online bookstore. Trust in this store is high.

This is great, just what the person wanted—or is it?

Some of the information collected by the agent and supplied in the Example 4-8 RDF/XML can be easily verified just by going out to the store web site. However, the issue of trust implied in the search results can’t be verified because the context of that trust—the originator of the statement about trust—is gone.

The RDF supplied in Example 4-13 is modified to use a higher-order statement supplying information about the originator of the trust specification. The modified RDF is shown in Example 4-14.

<?xml version="1.0"?> <rdf:RDF xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#" xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/"> <rdf:Description rdf:about="http://www.somebookstore.com" rdf:bagID="s1"> <pstcn:name>Some Bookstore</pstcn:name> <pstcn:storeType>bookstore</pstcn:storeType> <pstcn:trustLevel>High</pstcn:trustLevel> </rdf:Description> <!--The statement about the statement--> <rdf:Description rdf:about="http://burningbird.net/schema/ShelleyPowers"> <pstcn:recommendedBy rdf:resource="#s1" /> </rdf:Description> </rdf:RDF>

With this modification, the search engine results would be:

Some Bookstore, found at http://www.somebookstore.com/, is an online bookstore. Trust in this store is high. The assertion about the type of store and the trust in the store is provided by Shelley Powers.

Now the person shopping for an online bookstore has the information necessary to verify the source of the level of trust. Of course, the person would then have to determine if the source of the information is someone who can also be trusted. (Trust me. I can be trusted.)

Metadata about statements

Another use of reification is to record metadata information about a specific statement. For instance, if the statement about the resource (not the resource itself) is valid only after a specific date or only within a specific area or use, this type of information can be recorded using reification. Reification should be used because statement properties would associate the information directly to the resource, rather than to the statement.

One of the problems with the web today is that so many links to sites are obsolete, primarily because the original resource has been removed or moved to a new location. Web pages can have an expiration date attached to them, but that’s not going to help when adding a link to the web resource among your own pages. It’s the link or reference that needs to age gracefully, not the original resource.

To solve this, valid date information can be attached to the reference to the web resource, rather than being attached directly to the resource itself.

In Example 4-15, very simple RDF is used to describe a resource, an article, containing vacation and travel spot information. Attached to this recommendation is a constraint that the reference to this article is valid only for the year 2002.

<?xml version="1.0"?>

<rdf:RDF

xmlns:rdf="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#"

xmlns:pstcn="http://burningbird.net/postcon/elements/1.0/">

<rdf:Description>

<rdf:subject rdf:resource="http://burningbird.net/somearticle.htm" />

<rdf:predicate rdf:resource=

"http://burningbird.net/schema/Recommendations" />

<rdf:object>Vacation and Travel Spots</rdf:object>

<rdf:type rdf:resource="http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#Statement" />

<pstcn:validFor>2002</pstcn:validFor>

</rdf:Description>

</rdf:RDF>By using reification, we’ve attached a valid date range to the reference to the article rather than directly to the article. We’re saying that this reference (link) is valid only in the year 2002, rather than implying that the article the link is referencing is valid only in the year 2002.

Get Practical RDF now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.