Preface

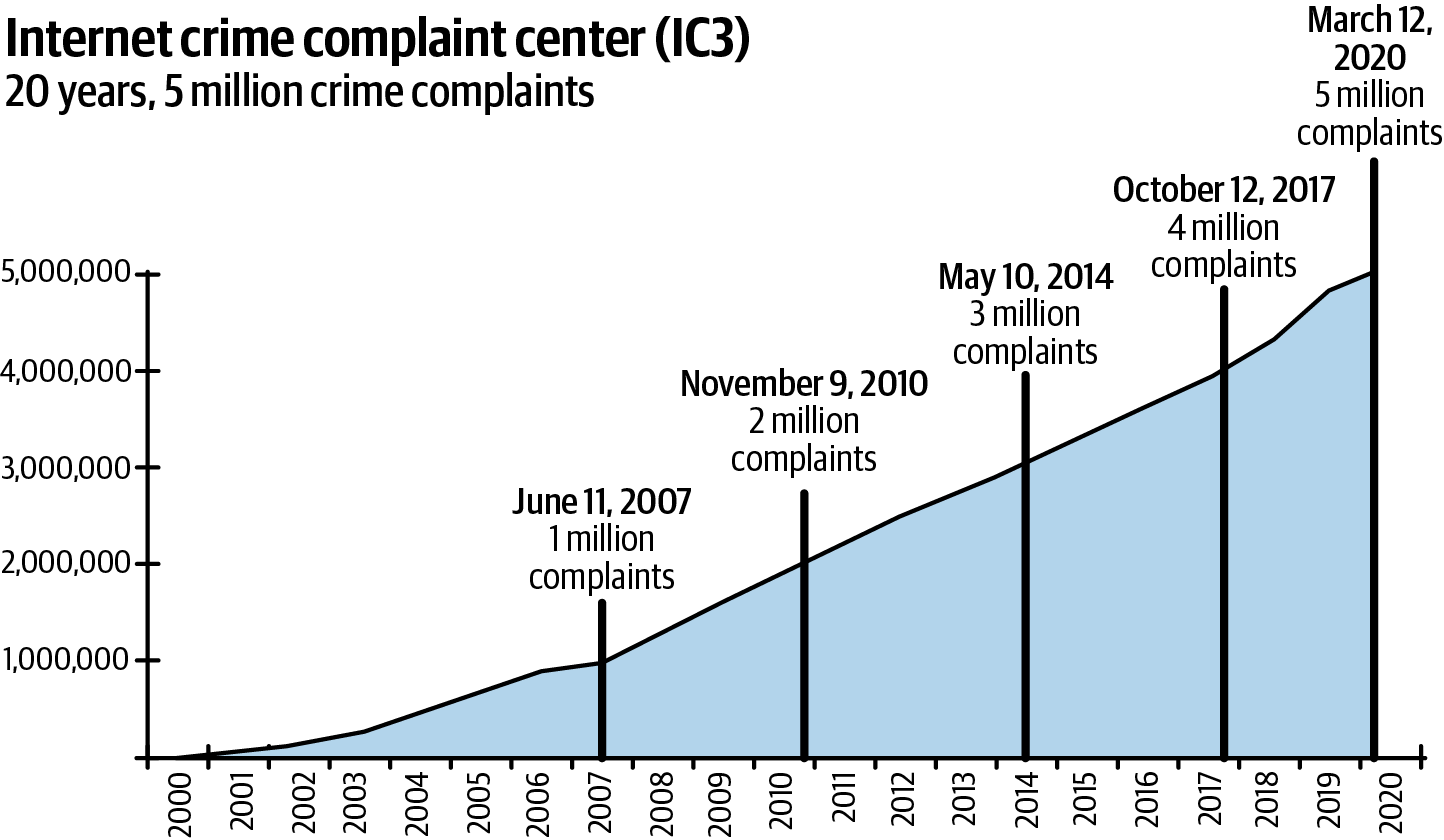

âWith commerce comes fraud,â wrote Airbnb cofounder Nathan Blecharczyk back in 2010, and itâs safe to say that the maxim has proven itself over and over in the years since then.1 Global online sales reached nearly $4.29 trillion in 2020, with more than $1 out of every $5 spent online. Fraudsters follow the money, making online fraud bigger, smarter, and bolder than ever (Figure P-1).

Figure P-1. Twenty years of internet crime complaints from the IC32

Fraud fighters, with their heads down in the data, excel at identifying new suspicious patterns and tracking down perpetrators. The constant pressure of fraud prevention means that often, day-to-day activities prevent fraud fighters from taking a breath, putting their head above the parapet, and looking around to see whatâs happening outside their company or their industry. The purpose of this book is to provide a wider and more strategic perspective as well as hands-on tips and advice.

During our time in fraud prevention, we have been privileged to have the chance to talk to and see data and trends from a wide range of merchants and organizations. Itâs that breadth that we want to share in this book.

Introduction to Practical Fraud Prevention

Online fraud has been around almost as long as online banking and online commerce: fraudsters go where the money is and wherever they can spot an opportunity. Itâs worth noting right at the start that when we refer to fraudsters, weâre talking about threats external to a business; this book does not discuss internal fraud or risk or employee integrity issues. Thereâs certainly enough to be said about external fraud onlineâa problem that businesses have been worrying about for decades now. Julie Fergerson, CEO of the Merchant Risk Council, remembers the early days of ecommerce 20 years ago, when sheâd help clients set up stores online and watch in horrified awe as fraud attacks would hit the very first weekâor sometimes even the first dayâof a shopâs existence.

At that time, there was often a physical aspect to online fraud. Card skimming was common as a means of stealing physical card information, perhaps carried out during a legitimate transaction or at an ATM. The card information might be used online to make purchases, or fake cards might be created to attempt transactions in physical stores. Sometimes the card data ended up online, on the forums that were quickly developing to enable criminals to interact with one another on the internet. Other times, the fraud was very simple, with a cashier just copying the card information and attempting to use it to make purchases online.

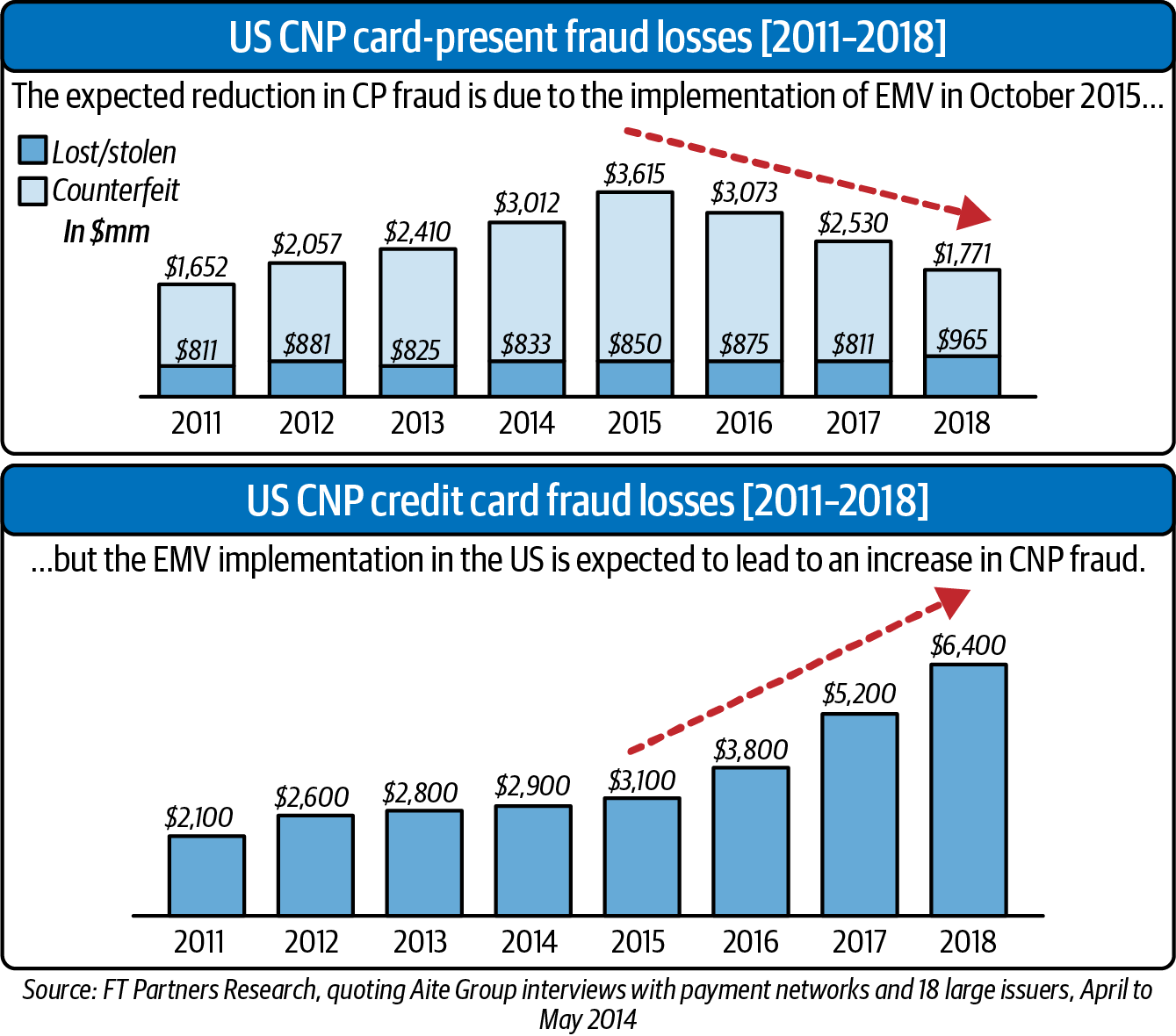

Card-present fraud hasnât entirely disappeared, but thereâs no question that a combination of chip and pin technology for card-present transactions and the sheer scale of online interactions and commerce has put card-not-present fraud center stage (Figure P-2). One 2021 study found that 83% of all fraud attacks involving credit, debit, or prepaid cards occurred online.3 Thatâs the world in which fraud prevention teams now live and breathe.

Figure P-2. Credit card fraud and ID theft in the United States from 2011 to 20184

The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020 accelerated digital transformation of all kinds as people adapted to the convenience and temporary necessity of shopping and interacting online. One report found that in 2020, 47% of people opened a new online shopping account, while 35% opened a new social media account and 31% opened an online banking account.5 All of this presents financial opportunities for online companiesâbut not without fraud risks. Nearly 70% of merchants said chargeback rates rose during the pandemic, and many reported high levels of account takeover (ATO) attempts as well.6 Given that consumers report the intention to continue their online purchasing and banking habits even once thereâs no pandemic pressure to do so, itâs reasonable to assume the fraud threat will continue as well.

Fraud attempts have become far more sophisticated, as well as more common. Fraudsters use elaborate obfuscation, an army of mules around the world, and even tools that capture information about a userâs browser and device when they visit a site so that this can be echoed as part of an ATO disguise. Phishing attempts, which drive much online fraud with their resultant stolen data, have evolved from the âNigerian princeâ scams of 10 or 15 years ago into subtle missives that mimic the tone, layout, and logos of emails sent from providers to the companies that use them, often targeting companies based on which providers they use. And donât even get us started on the intricacies of romance scams, IT repair scams, catfishing, and other social engineering schemes.

Fraudsters operate within what is now a highly sophisticated online criminal environmentâone which the FBI estimates stole more than $4.2 billion in 2020.7 Fraud is sometimes referred to as being part of the wider world of cybercrime, and other times as being connected to it but separate. In either case, thereâs no doubt that these connections are an important part of the scale and success many fraudsters achieve today. A wealth of stolen data is available for purchase to use in attacks, and technically focused cybercriminals create programs and apps that fraudsters can use to disguise themselves online quickly, and often in an automated fashion. Graphic designers, SEO experts, website developers, and more all support schemes involving fake sites created to trick consumers into giving up their data or placing fake orders. We wonât delve into the complex world of cybercrime more generally in this book, but we will mention aspects of the cybercriminal ecosystem when relevant.

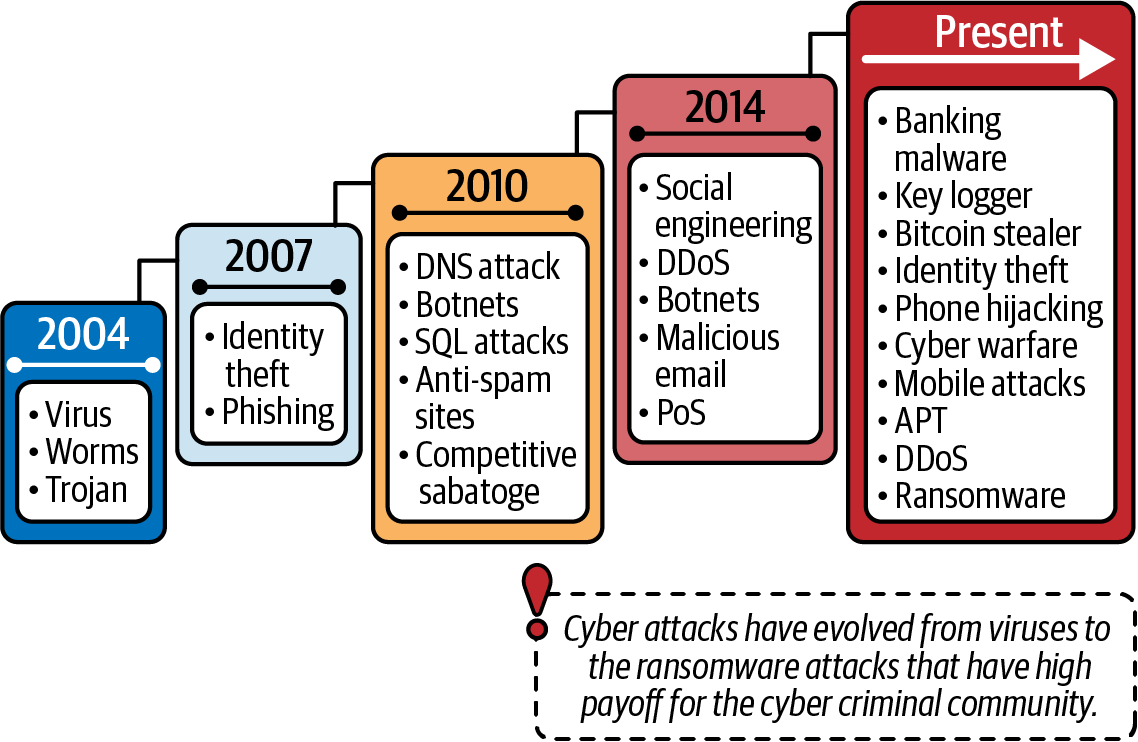

Fraud attacks have evolved within the banking and fintech worlds too (Figure P-3). Quite early on, fraudsters developed an appetite for higher profits. Attacks on individual consumers have existed from the beginning, but fraudsters who were able to carry out malware-based cyberattacks quickly became a more serious threat. Social engineering tactics focused on business email compromise (BEC) fraud, in which a fraudster could cash in big with a single unauthorized transfer, if they were lucky enough to succeed. Over the years, banks built up stronger defenses against the attacks of the early days, and many fraudsters âmigratedâ to targeting younger fintech companies and/or exploiting the vulnerabilities on the consumer side of banking. More recently, malware has been combined with social engineering, as discussed in Chapter 14.

Figure P-3. The development of fraudster attack methods and sophistication within a banking context

Of course, online fraud prevention has increased in sophistication as well. Where once the industry was dominated by rules engines, now machine learning supplements most systems to add its speed and excellence at spotting patterns to a fraud systemâs efforts. This has enabled more decisions to be automated, more quickly. Diverse vendors of data enrichment for many kinds of data have sprung up, though as a number of these have been acquired by larger players in recent years, it will be interesting to see how this field develops.

The relationship between fraudsters and fraud prevention is often described as an arms race, with each side continually attempting to create or uncover new vulnerabilities or tools that will give them an edge. Sometimes one side appears to have the upper hand, and other times the other side does. Fraudsters are unlikely to give up the battle while there is so much money to be made, and fraud prevention teams can never afford to take their eyes off the game knowing that fraudsters will pounce on any weakness.

One advantage that fraud prevention teams can develop is strong, collaborative relationships, both with fraud fighters at other companies and with other departments in their own company. While working on this book, we were surprised how many times the topic of collaboration came up, and in how many different contexts. Working with fraud teams from other companies, or within other departments, or convening and sharing ideas, new trends, and tips through forums, roundtables, reports, and so on, was key to the way many fraud managers keep track of whatâs going on in the industry and ensure that their teams are not falling behind.

Similarly, developing close, trusting relationships with departments such as customer support, marketing, sales, legal, and logistics/supply can give fraud prevention teams a real advantage in spotting and preventing the development of fraud trends, and in understanding and preparing for changes in the business or market approach. In the same way, educating other departments and upper management about fraud prevention and the challenges of balancing between friction and fighting fraud helps fraud teams look and stay relevant to the needs of the business and position themselves appropriately within the organization. All of this increases interdepartmental collaboration and makes it more likely that fraud teams will get the budget they need and the key performance indicators (KPIs) that make sense for both themselves and the company.

How to Read This Book

Ohad Samet, cofounder and CEO of TrueAccord and author of Introduction to Online Payments Risk Management (OâReilly), mentions âlack of dataâ as a common reason for failing to understand âwhat is going onâ in fraud analytics. He clarifies that this is often because âmaintaining event-based historical data is not anywhere near the top of these engineersâ mindsâ (once again, note the importance of educating other departments and management). Samet gives the example of point-in-time analysis (e.g., being able to train a predictive system using only data that was available at the time of the fraud attack, long before the financial loss became evident).

The authors of this book strongly agree with Samet that âlack of dataâ can be catastrophic, but not just because of its negative impact on the quality of your training sets. We see the urge of digging into event-based historical data as the key to a successful fraud prevention operation. A passion for root cause analysis, with an emphasis on behavioral analytics and âstorytellingâ research methodologies, is our creed.

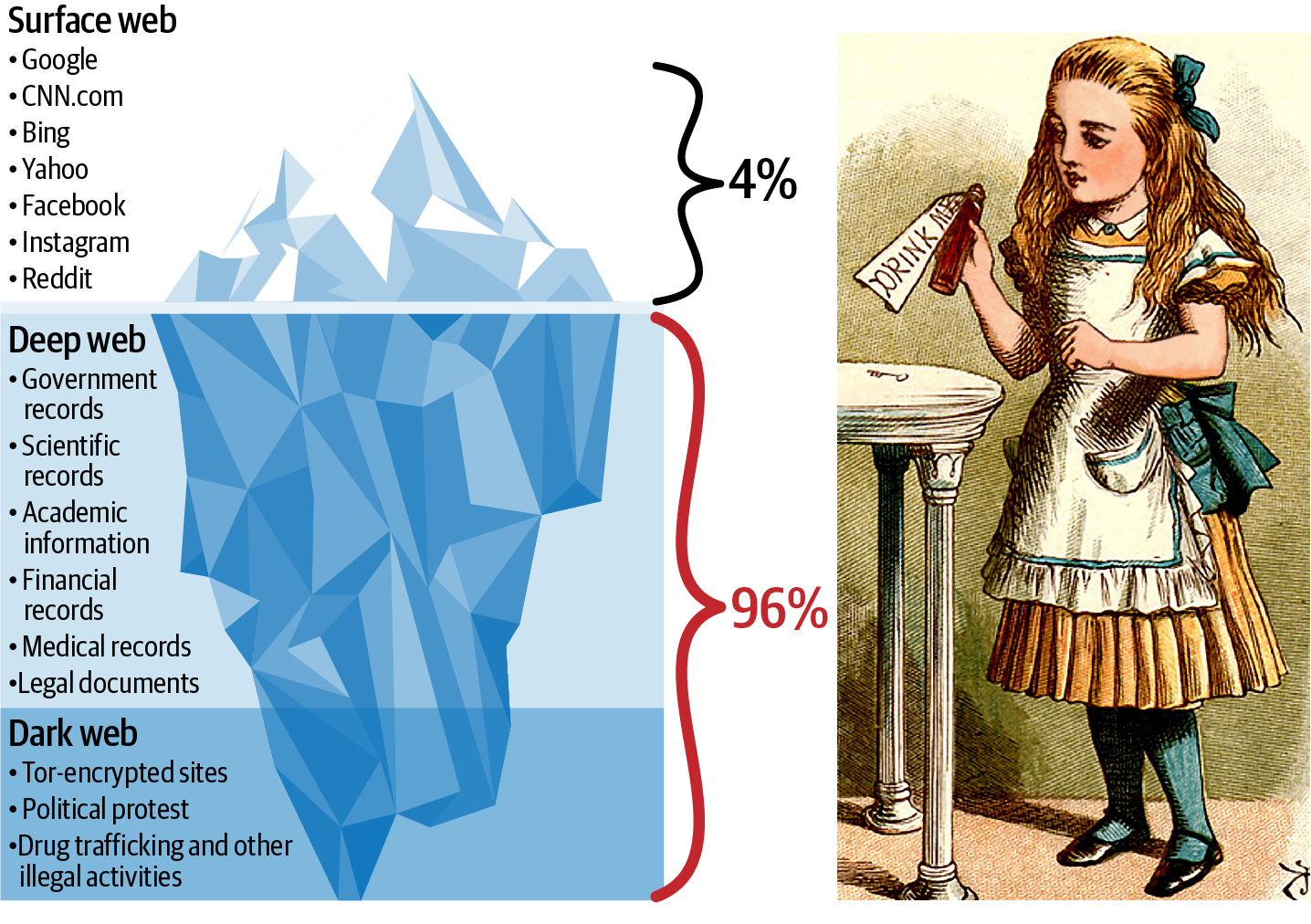

Therefore, we encourage you to read this book with the curiosity of a data addict. Like Alice in Wonderland, the historical data of your organization should be a rabbit hole that you should gladly jump into, feeling curiouser and curiouser and enticing others in your company to join the ride. We believe that robust fraud prevention solutions are built mainly by researchers who can explain the fraud from the perspectives of the attacker and the victim. To learn how to do so, one should definitely have broad horizons and a healthy dose of curiosity (sometimes you need to think like a fraudster to catch a fraudster) regarding the shockingly wide array of manipulative schemes out there. Open source researchers may gain some of this insight through web research (including the deep web and dark web), but we believe a good analyst can learn a lot from the combination of their imagination and their data (Figure P-4).

Figure P-4. Breakdown of the different parts of the internet (left); the continually curious Alice (right)8

In this book, you wonât find a checklist of steps you can take to stop fraud. Every business and every industry is different and has different priorities, needs, and structure. Fraud prevention must take all of them into account. Moreover, we have tried not to be too specific about particular tricks that can be used to catch fraudsters, because we know perfectly well that if we were, this book would become a favorite on fraudster forums within a month and the tricks would become useless soon afterward. Instead, we have tried to provide concepts and best practices that are helpful in different situations. We have also tried to make suggestions using features that are inherent to the nature of the challenge being faced, rather than ones that could be gamed and circumvented.

On a technical note, we wrote all the query examples in SQL, but they can easily be translated to PostgreSQL if necessary. Of course, you must adapt the queries to the specific tables of the database youâre working with (e.g., replace the generic hypothetical table we called CUSTOMERS with the name of the table that holds the relevant data for your use case). We have tried to present the queries throughout the book in a way that is easy for the reader to adapt to their own companyâs setup and preferred technologies. For example, we happen to like DataGrip and MySQL Workbench for working with SQL and Jupyter Notebook for working with Python, but whatever your companyâs or teamâs preferences are will work just as well when it comes to using the suggestions in this book.

We organized many of the chapters by attack type, under the industries for which they are most relevant. For example, we placed the chapter on stolen credit card fraud in the part of the book on ecommerce, even though stolen credit card fraud touches many other elements of the online criminal ecosystem and is part of many other attack methods. Similarly, the chapter on account takeover is in the part of the book covering banking.

Our main motivation for this structure is to make it easy for fraud analysts specializing in a particular industry to find the chapters most relevant to them. We do encourage you to look at the sections in every chapter of the book, though, to see which parts may be of interest, even if they are not in the part of the book pertaining to your industry. We have done our best to ensure that although the examples given relate to the industry in whose section the chapter falls, the discussion, suggestions, and mitigation techniques are relevant across industries.

In the same spirit, we have discussed different data points, or prevention tactics, within the context of the problem they are typically used to solve. So, for example, physical address analysis and reshipper detection are discussed in the chapter on address manipulation, while login analysis and inconsistency detection are discussed in the chapter on account takeover. We did initially consider keeping the âattackâ and âdefenseâ elements separateâso that, for example, address manipulation and physical address analysis would each have their own chapterâbut we felt that pairing the elements gave a much richer context for each part and kept the context far closer to what fraud prevention teams work with on a daily basis.

For the purposes of clarity, in each chapter we explore a data point separately, breaking each one down in the way that we hope will be most helpful. But in reality, when using this knowledge and the techniques suggested in analyzing user actions and profiles, you would put everything you learn about the individual data points together in order to form a storyâoften, two stories side by side: the legitimate story and the fraudulent story. Ultimately, you decide which is more plausible.

Context is absolutely crucial here. Say you have analyzed the IP and found a proxy, and the email address includes a lot of numbers. Perhaps the shipping address is that of a known reshipper. Thereâs a clear fraud story there. But what if the numbers are ones believed to be lucky in China, and the reshipper is one that reships to China? Then the proxy makes senseâthis is a strong legitimate story.

Making the data points analysis an integral part of the fraud types discussion, rather than splitting it off into a separate section, will, we hope, act as a constant reminder that these data points must been seen in the full context of the other data points involved, the business, the industry, and of course, the type of fraud attack.

Table P-1 is a guide to which data points are analyzed and which tactics are discussed in each chapter. You should feel free to skim or skip to the parts of chapters that discuss the mitigation techniques you are most interested in, though we do recommend that each of you reads Chapters 1 through 5 first, regardless of your industry.

| Chapter | Topic | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Part I: Introduction to Fraud Analytics | ||

| Chapter 1, âFraudster Traitsâ | An introduction to walking a mile in the fraudsterâs shoes | Address verification service (AVS) manipulation examples |

| Chapter 2, âFraudster Archetypesâ | The basics of understanding the different types of attacker youâre likely to see | Manually evaluating four transactions originating from a single IP |

| Chapter 3, âFraud Analysis Fundamentalsâ | The basics of the practical analytics approach used throughout the book | Login density anomaly; SQL to generate userâs histogram of abnormal number of daily logins |

| Chapter 4, âFraud Prevention Evaluation and Investmentâ | Building frameworks for strong fraud prevention teams | |

| Chapter 5, âMachine Learning and Fraud Modelingâ | A discussion about the place of modeling in fraud fighting | |

| Part II: Ecommerce Fraud Analytics | ||

| Chapter 6, âStolen Credit Card Fraudâ | Typical flow of stolen credit card monetization, followed by a general discussion on comparing IP data to user data | IP analysis: proxy detection, including data source examples; IP categorization using traffic breakdowns with SQL and Python |

| Chapter 7, âAddress Manipulation and Mulesâ | Physical goods theft via shipping manipulation | Address misspelling; SQL to find common typos or variations on city names Python to spot reshipping services by velocity of address repetition |

| Chapter 8, âBORIS and BOPIS Fraudâ | Fraud associated with Buy Online, Return In Store (BORIS) and Buy Online, Pick up In Store (BOPIS) programs | Linking analytics; detecting a fraud ring Analyzing potential mule operations with SQL |

| Chapter 9, âDigital Goods and Cryptocurrency Fraudâ | Fraud associated with digital goods, including fiat-to-crypto transactions; note that antiâmoney laundering (AML) and compliance relating to cryptocurrency are discussed in Chapter 22 | User profiling: age bucketing to spot potential social engineering |

| Chapter 10, âFirst-Party Fraud (aka Friendly Fraud) and Refund Fraudâ | First-party fraud, aka friendly chargebacks, with a focus on ecommerce | Refund request word clouds and supporting tools for customer care teams with SQL and Python |

| Part III: Consumer Banking Fraud Analytics | ||

| Chapter 11, âBanking Fraud Prevention: Wider Contextâ | Wider context for banking fraud | |

| Chapter 12, âOnline Account Opening Fraudâ | Reasons to open fraudulent accounts and ways to catch those accounts; includes references to money muling | Applying census data to fraud prevention |

| Chapter 13, âAccount Takeoverâ | Types of ATOs and how to catch them | Login analysis and inconsistency detection with SQL |

| Chapter 14, âCommon Malware Attacksâ | Malware attacks, particularly as used in conjunction with social engineering | |

| Chapter 15, âIdentity Theft and Synthetic Identitiesâ | Complexities of identifying and combating cases of actual stolen identity (rather than stolen and misused individual data points connected to a real identity) | Personal identifiable information (PII) analysis and identity discrepancy detection |

| Chapter 16, âCredit and Lending Fraudâ | Credit fraud and abuse, including stimulus fraud | Email domain histogram with SQL |

| Part IV: Marketplace Fraud | ||

| Chapter 17, âMarketplace Attacks: Collusion and Exitâ | Collusion and exit fraud; that is, when more than one account colludes to defraud the marketplace | Peer-to-peer (P2P) analysis; seller-buyer detection with SQL and Python |

| Chapter 18, âMarketplace Attacks: Seller Fraudâ | Forms of fraud carried out by marketplace sellers leveraging their position in the ecosystem | Seller reputation analysis and feedback padding detection using Python |

| Part V: AML and Compliance Analytics | ||

| Chapter 19, âAntiâMoney Laundering and Compliance: Wider Contextâ | Wider context for AML and compliance | |

| Chapter 20, âShell Payments: Criminal and Terrorist Screeningâ | Concealing money movement in various ways, including money muling; also looks at criminal and terrorist screening | Credit scores and transaction analysis for money mule detection with SQL |

| Chapter 21, âProhibited Itemsâ | Prohibited items and the wide variety of thorny issues associated with dealing with them | Standard deviation/RMSE analysis for product popularity with SQL |

| Chapter 22, âCryptocurrency Money Launderingâ | Why cryptocurrency has become popular for money laundering | Blockchain analytic data sources |

| Chapter 23, âAdtech Fraudâ | Bot fraud identification | Hijacked device identification |

| Chapter 24, âFraud, Fraud Prevention, and the Futureâ | Collaboration |

Who Should Read This Book?

Primarily, fraud analysts! The main audience we had in mind as we wrote this book was the smart, dedicated, and creative collection of folks we know who fight the good fight against fraud in their organizations, and in some cases lead fraud operations in those organizations. We hope the wider context provided in this book helps you see your own work in the context in which it belongs. We also hope the structure and framework we provide for different types of fraudsters, attack methods, and identification and mitigation efforts help you get things clearer in your own headâsomething that can be challenging when youâre always focused on making sure chargebacks remain low while approval rates remain high. We hope this book is, as it says on the cover, practical and useful. And we hope it reminds you that, whatever todayâs challenges are, you are never alone; you are part of a community of passionate fraud fighters who want to catch fraud, protect their companies, and get things right as much as you do.

We also hope this book will be valuable in training new fraud analysts, introducing them to the field, and giving them practical tips and even code to run. Having a wider understanding of online fraud, in a variety of contexts and through a variety of attack methods, will help new analysts immeasurably as they come to grips with their new challenges.

The nonfraud folks you work with regularly, such as software engineers or data scientists, who may have some working understanding of fraud prevention but who donât live and breathe fraud fighting in the way that your own team does, may also find this book interesting and beneficial, giving them valuable additional context for the work you engage in together. We hope it makes your partnership stronger, smoother, and even more successful.

As well, we hope youâll find this book helpful in introducing key concepts of fraud and fraud prevention to others in your organization who have no experience in fraud. As we emphasize repeatedly throughout this book, both collaboration with other departments and representing fraud prevention efforts appropriately to upper management are crucial in achieving true success as a fraud prevention department.

The context in which fraud analysts work is, frankly, coolâeven if most fraud fighters donât recognize that or think about it day to day. Youâre fighting cybercriminals who use a range of ingenious techniques to try to trick you and steal from the business. Once others in your company understand this and some of the context behind it, they will care a whole lot more about what you do and will want to help you do it.

It is important to note that in general, this book reflects and speaks to the perspective of a fraud prevention professional or team, and also an AML professional or team in the sense that AML traces patterns, detects anomalies, and acts to prevent them. The compliance-focused side of AML, the perspective of data scientists or compliance experts or financial analysts, is not reflected here. There are other books that focus on these domains and aim to talk to and help the experts within them.

It was important for us to focus firmly on the fraud prevention side of things because in some ways, the fraud prevention industry is underserved in terms of educational opportunities. There are numerous excellent higher education courses and certifications (and even YouTube videos) that individuals can use to further their understanding of data science and become qualified in its use. ACFE runs diverse courses that enable participants to become Certified Fraud Examiners so that they can help businesses fight money laundering, insider fraud, financial fraud, and so forth. But there is no equivalent organization, course, or set of materials to help fraud analysts learn and stay up to date with fraud prevention within ecommerce, online marketplaces, or fintech. (Though the Merchant Risk Council is working on training materials and tests for junior fraud analysts, so watch that space!)

There is one advantage fraud fighters have that does balance out this lack to some degree. Fraud prevention, as an industry, has a particular advantage in that its professionals are unusually willing to collaborate, sharing experiences, tips, and even data with one another. This plays out in conferences, forums, and roundtables. Just as fraudsters work together sharing information about sitesâ weaknesses and how they can be leveraged, and sometimes work together to form combined attacks, so fraud fighters work together to combat their shared enemy. As Karisse Hendrick, founder and principal consultant at Chargelytics Consulting and host of the popular Fraudology podcast, says, this really is a âsuperpower,â and fraud fighters who draw on this community spirit and nurture relationships within the industry can have a powerful advantage in fighting fraud.

This drive for collaboration is, in a sense, only logical, since it extends the understanding and effectiveness of fraud fighters and helps outweigh the extent to which criminals often work together to defraud companies. Itâs also a reflection of the drive for justice that many of the fraud prevention experts we quote in this book feel animates their work and that of their team. Carmen Honacker, head of Customer and Payment Fraud at Booking.com, offers a delightful story about the time her card details were stolen and the bank called to inform her of the suspicious activity. Using her fraud prevention background and skills, she tracked down the thieves and then sent the police to arrest them. The bank managers, when she told them, were astonished and impressed. Fraud fighters canât manage that for every suspicious case they encounter, but the drive for justice is definitely strong in the industry.

Domain expertise is hard-won knowledge for fraud fighters. This is partly because of the lack of courses and certifications, but also because, from a data perspective, there just arenât that many fraudsters. Itâs a tiny minority of users who have an enormous impact. You canât fight the problem purely with data or machines (though as we will discuss in the book, data and machine learning can be extremely helpful). You simply need to know a lot about how fraudsters work and how your company works. This takes time, research, and ongoing effort; a fraud prevention expertâs perspective must evolve as consumer behavior, fraudster behavior, and company priorities do.

We sincerely hope this book will help fill in a little of that information gap in the fraud prevention industry. Whether youâre just starting out in your career and looking for an overview, or youâre an expert with decades of experience wanting to dig into various issues or patterns, build a framework for your accumulated knowledge, or look for new ways to combat challenges, we hope you enjoy this book and find it helpful. And we wish you the best in the ongoing, ever-evolving battle against crime that characterizes the fraud prevention profession.

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

-

Indicates new terms, URLs, email addresses, filenames, and file extensions.

Constant width-

Used for program listings, as well as within paragraphs to refer to program elements such as variable or function names, databases, data types, environment variables, statements, and keywords.

Constant width bold-

Shows commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

Tip

This element signifies a tip or suggestion.

Note

This element signifies a general note.

Warning

This element indicates a warning or caution.

OâReilly Online Learning

Note

For more than 40 years, OâReilly Media has provided technology and business training, knowledge, and insight to help companies succeed.

Our unique network of experts and innovators share their knowledge and expertise through books, articles, and our online learning platform. OâReillyâs online learning platform gives you on-demand access to live training courses, in-depth learning paths, interactive coding environments, and a vast collection of text and video from OâReilly and 200+ other publishers. For more information, visit https://oreilly.com.

How to Contact Us

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

- OâReilly Media, Inc.

- 1005 Gravenstein Highway North

- Sebastopol, CA 95472

- 800-998-9938 (in the United States or Canada)

- 707-829-0515 (international or local)

- 707-829-0104 (fax)

We have a web page for this book, where we list errata, examples, and any additional information. You can access this page at https://oreil.ly/practical-fraud-prevention.

Email bookquestions@oreilly.com to comment or ask technical questions about this book.

For news and information about our books and courses, visit https://oreilly.com.

Find us on Facebook: https://facebook.com/oreilly

Follow us on Twitter: https://twitter.com/oreillymedia

Watch us on YouTube: https://youtube.com/oreillymedia

Acknowledgments

Weâve had so much support from many amazing people throughout the process of writing this book. Thank you so much to everyone who helped make it a reality! We would like to give an especially big thank-you to the following people.

Our greatest thanks go to the queen of collaboration, Karisse Hendrick, who originally suggested us for this project when the OâReilly editors decided they wanted a book about fraud prevention, and who encouraged us throughout. Weâre indebted to her for her enthusiasm, her willingness to share her experiences, and her conviction that we could cover all the topics we wanted to in a single book. (It seems she was right.)

We would also like to thank our wonderful technical experts and reviewers: Alon Shemesh, Ben Russell, Brett Holleman (whose excellent technical review was matched by the excellence of his additional and very relevant anecdotes), Gil Rosenthal, Ken Palla, Mike Haley, Netanel Kabala, Jack Smith, and Yanrong Wang. They helped us polish and clarify our explanations, pointed out things that needed to be added, and generally made sure our content matched the trends they had observed in their fraud-fighting work. Any remaining mistakes are, of course, our own.

This book could not have happened without the conversations and interviews we were lucky enough to carry out with a number of experts from the fraud-fighting space, who so generously shared their time, experience, and advice. Our thanks go to Aamir Ali, Arielle Caron, Ben Russell, Carmen Honacker, Dave Laramy, Elena Michaeli, Gali Ellenblum, Gil Rosenthal, Professor Itzhak Ben Israel, Jordan Harris, Julia Zuno, Julie Fergerson, Ken Palla, Keren Aviasaf, Limor Kessem, Maximilian von Both, May Michelson, Maya Har-Noy, Mike Haley, Nate Kugland, Nikki Baumann, Noam Naveh, Ohad Samet, Rahav Shalom Revivo, Raj Khare, Sam Beck, Soups Ranjan, Tal Yeshanov, Uri Lapidot, Uri Rivner, and Zach Moshe; to Arik Nagornov, Yuval Rubin, Lia Bader, and Lisa Toledano from DoubleVerify whose research we discuss in Chapter 23; and to Uri Arad and Alon Shemesh, without whose years of support and guidance we would not have been in a position to write this book in the first place.

Weâre grateful to DoubleVerify and Identiq for being not only willing to let us write the book, but also actively supportive of our efforts.

Weâd like to thank the fantastic team at OâReilly, and particularly our editorsâCorbin Collins, Kate Galloway, and Audrey Doyleâwho picked up on and fixed all the little errors and lacunae that we would never have noticed ourselves.

And weâre especially grateful to our respective spouses, Ori Saporta and Ben Maraney, both of whom learned far more about fraud prevention as a result of this book than theyâd bargained for. Without their encouragement, patience, and support, this book would not have happenedâor at least, it certainly wouldnât have been written by us.

1 Nathan Blecharczyk, âHard Problems, Big Opportunityâ, The Airbnb Tech Blog, November 7, 2010.

2 FBI, âInternet Crime Complaint Center Marks 20 Yearsâ, May 8, 2020.

3 Feedzai, Financial Crime Report: The Dollar Takes Flight, Q2 2021 edition.

4 Emmanuel Gbenga Dada et al., âCredit Card Fraud Detection using k-star Machine Learning Algorithmâ (paper, 3rd Biennial Conference on Transition From Observation To Knowledge To Intelligence, University of Lagos, Nigeria, August 2019).

5 James Coker, âA Fifth of Consumers Affected by Identity Fraud in 2020â, Inforsecurity Magazine, November 23, 2020.

6 DJ Murphy, âCovid Changed Chargebacks for E-Commerce Merchants, Says Reportâ, Card Not Present, June 3, 2021.

7 Ionut Ilascu, âFBI: Over $4.2 Billion Officially Lost to Cybercrime in 2020â, Bleeping Computer, March 18, 2021.

8 Sir John Tenniel, Drink Me, in The Nursery âAliceâ by Lewis Carroll, illustrations by John Tenniel (London: Macmillan and Co., 1889), via Wikimedia Commons.

Get Practical Fraud Prevention now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.