Life is all about making choices, and the time you spend in Photoshop is no exception. Perhaps the biggest decision you’ll make is which part of an image to edit—after all, your edits don’t have to affect the whole thing. Using a variety of tools, you can tell Photoshop exactly which portion of the image you want to tinker with, right down to the pixel, if you so desire. This process is called making a selection.

As you’ll learn in this chapter, Photoshop has a bunch of tools that you can use to create selections based on shape, color, and other attributes. You can also draw selections by hand, although that requires a bit of mouse prowess. True selection wisdom lies in learning which tool to start with, how to use the tools together, and how to fine-tune your selections quickly and efficiently. The following pages will help you with all that and then some.

What’s so great about selections, anyway? Lots. After you make a selection, you can do all kinds of neat things with it:

Fill it with color or pixels from the image’s background. Normally, the Edit→Fill command or a Solid Color Adjustment layer floods an entire layer with color, but by creating a selection first, you can color just that area. You can also use the Fill command in conjunction with a selection to delete a person from your photo as if they were never there (see Using Content-Aware Fill).

Add an outline. You can add a stroke (Photoshop’s term for an outline) to any selection. For instance, you can use selections to give a photo a black border or to circle yourself in a group photo (Stroking (Outlining) a Selection). (In Photoshop CS6 you can also add a stroke to shapes and paths; you’ll learn all about that on Customizing Stroke Options.)

Move it around. To move part of an image, you need to select it first. You can even move selections from one document to another, as discussed on Moving Selections. For example, a little head swapping is great fun after family reunions and breakups. If you want to stick your ex’s head onto a ballerina’s body, hop on over to Saving a Selection.

Resize or transform it. Need to change the size or shape of the selection before you manipulate the pixels inside it? No problem: Once you’ve made a selection, you can transform it into whatever size or shape you need (Creating a Border Selection). With this maneuver Photoshop won’t reshape any pixels that are in the selected area; it just changes the shape of the selection itself. This trick is handy when you’re trying to select part of an image that’s in perspective, as shown on Transforming a Selection.

Use it as a mask. When you create a selection, Photoshop protects the area outside it, so that anything you do to the image affects only the selected area. For example, if you paint with the Eraser tool (The Background Eraser) across the edge of a selection, it erases only the area inside the selection. Likewise, if you create a selection before adding a layer mask (Layer Blending), Photoshop loads the selected area into the mask automatically, letting you adjust only that part of the image. So selections are crucial when you need to correct color or lighting in just one area (Chapter 9), or change the color of an object (Changing Color).

This chapter discusses all these options and more. But, first, you need to understand how Photoshop indicates selections.

When you create a selection, Photoshop calls up a lively army of animated “marching ants” (shown in Figure 4-1). These tiny soldiers dutifully march around the edge of the selected area, awaiting your command. You can select part of a layer’s contents or everything on a single layer. Whenever you have an active selection (that is, whenever you see marching ants), Photoshop has eyes only for that portion of the document—any tool you use (except the Type, Pen, and shape tools) will affect only the area inside the selection.

Note

Selections don’t hang around forever—when you click somewhere else on your screen (outside the selection) with a selection tool, the original selection disappears, forcing you to recreate it. To find out how to save a selection so you can use it again later, flip to Saving a Selection.

Here are the commands you’ll use most often when making selections:

Select All. This command selects the whole document and places marching ants around the perimeter, which is helpful when you want to copy and paste an entire image into another program or create a border around a photo (see Stroking (Outlining) a Selection). To run this command, go to Select→All or press ⌘-A (Ctrl+A on a PC).

Deselect. To get rid of the marching ants after you’ve finished working with a selection, choose Select→Deselect or press ⌘-D (Ctrl+D). Alternatively, if you’ve got one of the selection tools activated in the Tools panel, you can click once outside the selection to get rid of it.

Reselect. To resurrect your last selection, choose Select→Reselect or press Shift-⌘-D (Shift-Ctrl-D). This command reactivates the last selection you made, even if it was five filters and 20 brushstrokes ago (unless you’ve used the Crop or Type tools since then, which render the Reselect command powerless). Reselecting is helpful if you accidentally deselect a selection that took you a long time to create. (The Undo command [⌘-Z or Ctrl+Z] can also help you in that situation.)

Inverse. This command, which you run by going to Select→Inverse or pressing Shift-⌘-I (Shift-Ctrl-I), flip-flops a selection to select everything that wasn’t selected before. You’ll often find it easier to select what you don’t want and then inverse the selection to get what you do want (the box on Selecting the Opposite has more on this useful technique).

Load a layer as a selection. When talking to people about Photoshop, you’ll often hear the phrase “load as a selection,” which is (unavoidable) Photoshop-speak for activating a layer that contains the object you want to work with and then summoning the marching ants so they run around that object; that way, whatever you do next affects only that object. To load everything that lives on a single editable layer as a selection, mouse over to the Layers panel and ⌘-click (Ctrl-click) the layer’s thumbnail (The Layers Panel). Photoshop responds by putting marching ants around everything on that layer. Alternatively, you can Control-click (right-click on a PC) the layer’s thumbnail and then choose Select Pixels from the resulting shortcut menu.

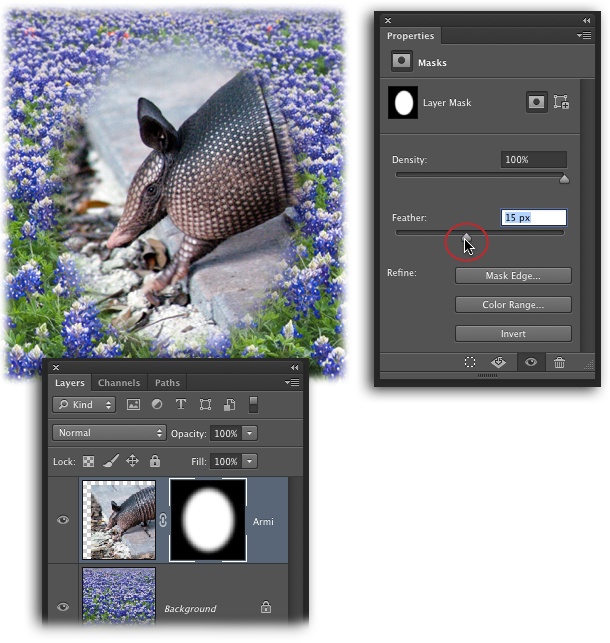

Figure 4-1. To let you know an area is selected, Photoshop surrounds it with tiny, moving dashes that look like marching ants. Here you can see the ants running around the armadillo. (FYI, the nine-banded armadillo is the state animal of Texas. Didn’t think you’d learn that from this book, did ya?)

Tip

Although you can find most of the commands in this list in the Select menu at the top of your screen (except for loading a layer as a selection), you should memorize their keyboard shortcuts if you want to be smokin’ fast in Photoshop.

Now it’s time to discuss the tools you can use to make selections. Photoshop has a ton of ’em, so in the next several pages, you’ll find them grouped according to which kind of selections they’re best at making.

Selections based on shape are probably the easiest ones to make. Whether the object you need to grab is rectangular, elliptical, or rectangular with rounded corners, Photoshop has just the tool for you. You’ll use the first couple of tools described in this section often, so think of them as your bread and butter when it comes to making selections.

Photoshop’s most basic selection tools are the Rectangular and Elliptical Marquees. Anytime you need to make a selection that’s squarish or roundish, reach for these little helpers, which live at the top of the Tools panel, as shown in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-2. You’ll spend loads of time making selections with the Rectangular and Elliptical Marquee tools. To summon this menu, click the second item from the top of the Tools panel and hold down your mouse button until the menu of additional tools appears.

To make a selection with either marquee tool, just grab the tool by clicking its icon in the Tools panel or by pressing M, and then mouse over to your document. When your cursor turns into a tiny + sign, drag across the area you want to select (you’ll see the marching ants appear as soon as you start to drag). Photoshop starts the selection where you clicked and continues it in the direction you drag as long as you hold down the mouse button. When you’ve got marching ants around the area you want to select, release the mouse button.

You can use a variety of tools and techniques to modify your selection, most of which are controlled by the Options bar (Figure 4-3). For example, you can do the following:

Move the selection. Click anywhere within the selected area and then drag to another part of your document (your cursor turns into a tiny arrow the second you release the mouse button after drawing a selection—as long as your cursor remains inside the selection, that is).

Tip

You can move a selection as you’re drawing it by moving your mouse while pressing the mouse button and the space bar. When you’ve got the selection where you want it, release the space bar—but not your mouse button—and continue drawing the selection.

Figure 4-3. Using the buttons in the Options bar, you can add to or subtract from a selection, as well as create a selection from two intersecting areas. Since all selections begin at the point where you first click, you can easily select one of these doors by dragging diagonally from the top-left corner to the bottom right as shown here. You can tell from the tiny + sign next to the crosshairs-shaped cursor that you’re in “Add to selection” mode, so this figure now has two selections: the blue door and the red door. In CS6 you get a handy overlay that displays the width and height info as you drag to create a selection (shown here). If you move a selection, you see X and Y axis info instead that indicates how far you’ve moved the selection in the document. Give this selection technique a spin by downloading the practice file, Doors. jpg, from this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds.

Add to the selection. When you click the “Add to selection” button in the Options bar (labeled in Figure 4-3) or press and hold the Shift key, Photoshop puts a tiny + sign beneath your cursor to let you know that whatever you drag across next will get added to the current selection. This mode is handy when you need to select areas that don’t touch each other, like the doors in Figure 4-3, or if you’ve selected most of what you want but notice that you missed a spot. Instead of starting over, you can switch to this mode and draw around that area as if you were creating a new selection.

Subtract from the selection. Clicking the “Subtract from selection” button (also labeled in Figure 4-3) or pressing and holding the Option key (Alt on a PC) has the opposite effect. A tiny – sign appears beneath your cursor to let you know you’re in this mode. Mouse over to your document and draw a box (or oval) around the area you want to deselect.

Intersect one selection with another. If you click the “Intersect with selection” button after you draw a selection, Photoshop lets you draw another selection that overlaps the first; the marching ants then surround only the area where the two selections overlap. It’s a little confusing, but don’t worry because you’ll rarely use this mode. The keyboard shortcut is Shift-Option (Shift+Alt on a PC). Photoshop puts a tiny multiplication sign (x) beneath your cursor when you’re in this mode.

Feather the selection. If you want to soften the edges of your selection so that it blends into the background or another image, use feathering. You can enter a value in pixels in this field before you create the selection, as it applies to the next selection you make. As you’ll learn later in this chapter, feathering a selection lets you gently fade one image into another. See the box on The Softer Side of Selections for more on feathering, including how to feather a selection after you create it.

Apply anti-aliasing. Turn on the Anti-alias checkbox to make Photoshop smooth the color transition between the pixels around the edges of your selection and the pixels in the background. Like feathering, anti-aliasing softens the selection’s edges slightly so that they blend better, though with anti-aliasing you can’t control the amount of softening Photoshop applies. It’s a good idea to leave this checkbox turned on unless you want your selection to have super crisp—and possibly jagged and blocky—edges.

Constrain the selection. If you want to constrain your selection to a fixed size or aspect ratio (so that the relationship between its width and height stays the same), you can select Fixed Size or Fixed Ratio from the Style pop-up menu and then enter the size you want in the resulting width and height fields. (Be sure to enter a unit of measurement into each field, such as px for pixels.) If you leave the Normal option selected, you can draw any size selection you want.

Here’s how to select two objects in the same photo, as shown in Figure 4-3:

Click the marquee tool icon in the Tools panel and choose the Rectangular Marquee from the pop-up menu (shown in Figure 4-2).

Photoshop remembers which marquee tool you last used, so you’ll see that tool’s icon in the Tools panel. If that’s the one you want to use, just press M to activate it. If not, in the Tools panel, click and hold whichever marquee tool icon is showing until the pop-up menu appears and then choose the tool you want.

Tip

To cycle between the Rectangular and Elliptical Marquee tools, press M to activate the marquee toolset and then press Shift-M to activate each one in turn. If that doesn’t work, make sure that a gremlin hasn’t turned off the preference that makes this trick possible. Choose Photoshop→Preferences→General (Edit→Preferences→General on a PC) and make sure the “Use Shift Key for Tool Switch” checkbox is turned on.

Drag to draw a box around the first object.

For example, to select the blue door shown in Figure 4-3, click its top-left corner and drag diagonally toward its bottom-right corner. When you get the whole door in your selection, release the mouse button. Don’t worry if you don’t get the selection in exactly the right spot; you can move it around in the next step.

Move your selection into place if necessary.

If you need to move the selection, just click inside the selected area (your cursor turns into a tiny arrow) and drag the selection box where you want it. You can also use the arrows on your keyboard to nudge the selection in one direction or another (you don’t need to click it first).

Click the “Add to selection” button in the Options bar and then select the second object by drawing a selection around it.

Photoshop lets you know that you’re in “Add to selection” mode by placing a tiny + sign below your cursor. Once you see it, mouse over to the second door and drag diagonally from its top-left corner to its bottom right, as shown in Figure 4-3. Alternatively, you can press and hold the Shift key to put the tool into “Add to selection” mode.

If you need to move this second selection around, do that before you release the mouse button or you’ll end up moving both selections instead of just one. To move the selection while you’re drawing it, hold down your mouse button, press and hold the space bar, and then move your mouse to move the selection. When it’s in the right place, release the space bar—but keep holding the mouse button—and continue dragging to draw the selection. This maneuver feels a bit awkward at first, but you’ll get used to it with practice.

Congratulations! You’ve just made your first selection and added to it. Way to go!

Tip

To draw a perfectly square or circular selection, press the Shift key as you drag with the Rectangular or Elliptical Marquee tools, respectively. If you want to draw the selection from the center outward (instead of from corner to corner), press and hold the Option key (Alt on a PC) instead. And if you want to draw a perfectly square or circular selection from the center outward, press and hold Shift-Option (Shift+Alt) as you drag with either tool. Be sure to use these tricks only on new selections—if you’ve already got a selection, the Shift key pops you into “Add to selection” mode.

The Elliptical Marquee tool works just like the Rectangular Marquee tool except that it draws round or oval selections. It’s a great tool for selecting eyes, circling yourself in a group photo (Stroking (Outlining) a Selection), or creating the ever-popular, oh-so-romantic, soft oval vignette shown in Figure 4-4.

Here’s how to create a soft oval vignette:

Open two images and combine them into the same document.

Simply drag one image from its Layers panel into the other document’s window, as shown on Moving Layers Between Documents.

Reposition the layers so the soon-to-be-vignetted photo is at the top of the Layers panel.

Over in the Layers panel, make sure that both layers are editable so you can change their stacking order. If you see a tiny padlock to the right of either layer’s name, double-click that layer’s thumbnail to make it editable. Then drag the layer containing the photo you want to vignette (in Figure 4-4, that’s the picture of the armadillo) to the top of the Layers panel.

Figure 4-4. By adding a layer mask (page 116) and then feathering a selection you’ve made with the Elliptical Marquee tool, you can create a quick two-photo collage like this one. Wedding photographers and moms—not to mention armadillo fans—love this kind of thing! By using the Properties panel to do your feather, you gain the ability to change the feather amount later on (provided you save the document as a PSD file). Once you get the hang of this technique, try creating it using the Ellipse tool set to draw in path mode instead, as described on page 572; it’s a little bit quicker and slightly more efficient.

Grab the Elliptical Marquee tool and select the part of the image you want to vignette (here, the armadillo’s head).

Peek at your Layers panel to make sure the correct image layer is active (the armadillo) and position your mouse near the center of the image. Press and hold the Option key (Alt on a PC), mouse over to the image, and drag to draw an oval-shaped selection from the inside out. When you’ve got the selection big enough, release the Option (or Alt) key and your mouse button.

Hide the area outside the selection with a layer mask.

You could simply inverse the selection (Meet the Marching Ants) and then press the Delete key (Backspace on a PC) to zap the area outside it, but that’d be mighty reckless. What if you changed your mind? You’d have to undo several steps or start over completely! A less destructive and more flexible approach, which you learned about back on Layer Blending, is to hide the area outside the selection with a layer mask. Over in the Layers panel, make sure you have the correct layer active (in this case, the armadillo) and then add a layer mask by clicking the tiny circle-within-a-square icon at the bottom of the panel. Photoshop hides everything outside the selection, letting you see through to the bluebonnet layer below. Beautiful!

Feather the selection’s edges by using the Properties panel’s Feather slider.

With the layer mask active, open the Properties panel by choosing Window→Properties. In the panel, drag the Feather slider to the right and Photoshop softens the selection right there in the document as you watch. (New in CS6, the Feather slider accepts decimal values!)

Choose File→Save As, and then pick Photoshop as the format.

Doing so lets you tweak the Feather amount later on by activating the layer mask and then reopening the Properties panel.

That armadillo looks right at home, doesn’t he? You’ll want to memorize these steps because this method is perhaps the easiest—and most romantic!—way to combine two images into a new and unique piece of art (although you’ll learn how to use the vector shape tools to do the same thing starting on Using Vector Masks).

The Marquee toolset also contains the Single Row Marquee and Single Column Marquee tools, which can select exactly one row or one column’s worth of pixels, spanning either the width or the height of your document. You don’t need to drag with your mouse to create a selection with these tools; just click once in your document and the marching ants appear.

You may be wondering, “When would I want to do that?” Not often, it’s true, but consider these circumstances:

Mocking up a web page design. If you need to simulate a column or row of space between certain areas in a web page, you can use either tool to create a selection that you fill with the website’s background color.

Create a repeating background on a web page. If you’re creating an image that you’ll use as a repeating background on a web page, select a horizontal row and then instruct your HTML-editing program to repeat or stretch the image as far as you need it. This trick can really decrease the time it takes to download a web page.

Stretching an image to fill a space. If you’re designing a web page, for example, you can use these tools to extend an image by a pixel or two. Use either tool to select a row of pixels at the bottom or side of the image, grab the Move tool by pressing V, and then tap the arrow keys on your keyboard while holding the Option key (Alt on a PC) to nudge the selection in the direction you need and duplicate it at the same time. However, a better option is to use Content-Aware Scale (see Content-Aware Scaling).

Making an image look like it’s melting or traveling through space at warp speed. You can use either tool to create a selection and then stretch it with the Free Transform tool (see Figure 4-5).

Note

Create your own speeding hen by downloading the practice file, Hen.jpg, from this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds.

Figure 4-5. Good luck catching this hen! To achieve this look, start by using the Single Column Marquee to select a column of pixels. Then “jump” the selection onto its own layer by pressing ⌘-J (Ctrl+J on a PC). Next, summon the Free Transform tool by pressing ⌘-T (Ctrl+T), and drag one of the square, white center handles leftward. Last but not least, add a gradient mask (page 278) and then experiment with blend modes until you find one that makes the stretched pixels blend into the image (for more on blend modes, see Chapter 7, page 280). Unfortunately you can’t activate the Single Row and Single Column Marquee tools with a keyboard shortcut; you’ve got to click their icons in the Tools panel instead.

Technically, vector shapes aren’t selection tools, but you can use them to create selections (turn to Drawing with the Shape Tools to learn more about vector shapes). Once you get the hang of using them as described in this section, you’ll be reaching for ’em all the time.

Perhaps the most useful of this bunch is the Rounded Rectangle tool. If you ever need to select an area that’s rectangular but has rounded corners, this is your best bet. For example, if you’re creating an ad for a digital camera, you can use this technique in a product shot to replace the image shown on the camera’s display screen with a different image. Or, more practically, you can use it to give your photos rounded corners, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Here’s how to round the corners of a photo:

Open a photo and double-click the Background layer to make it editable.

Because you’ll add a mask to the photo layer in step 5, you need to make sure the Background layer is unlocked or Photoshop won’t let you add the mask.

Activate the Rounded Rectangle tool in the Tools panel.

Near the bottom of the Tools panel lies the Vector Shape toolset. Unless you’ve previously activated a different tool, you’ll see the Rectangle tool’s icon. Click the icon and hold down your mouse button until the pop-up menu appears, and then choose the Rounded Rectangle tool.

Figure 4-6. If you’re tired of boring, straight corners on your images, use the Rounded Rectangle tool to produce smooth corners like the ones shown here. Be sure to put the tool in Path mode first using the pop-up menu near the far left of the Options bar, or else you’ll create a Shape layer that you don’t really need. You can use the same technique with the Ellipse tool to create the vignette effect shown in the previous section. To feather the mask after you’ve added it, activate it, choose Window→Properties, and then drag the Properties panel’s Feather slider to the right.

In the Options bar, set the tool’s mode to Path and change the Radius field to 40 pixels (or whatever looks good to you).

As you’ll learn on Drawing with the Shape Tools, the vector shape tools can operate in various modes. For this technique, you want to use Path mode. Click the pop-up menu near the left end of the Options bar (it’s probably set to Shape) and choose Path. Next, change the number in the Radius field, which controls how rounded the image’s corners will be: A lower number causes less rounding than a higher number. This field was set to 40 pixels to create the corners shown in Figure 4-6. However, you’ll need to use a larger number if you’re working with a high-resolution document.

Draw a box around the image.

Mouse over to your image and, starting in one corner, drag diagonally to draw a box around the whole image. When you let go of the mouse button, Photoshop creates a thin gray outline that appears atop your image called a path, which you’ll learn all about in Chapter 13. If you need to move the path while you’re drawing it, press and hold the space bar. If you want to move the path after you’ve drawn it, press A to grab the Path Selection tool (it looks like a black arrow and lives below the Type tool in the Tools panel), click the path to activate it, and then drag to move it wherever you want.

Hide the area outside the path by adding a layer mask.

In the Layers panel, click the photo layer once to activate it and then add a vector layer mask by ⌘-clicking (Ctrl-clicking) the tiny circle-within-a-square icon at the bottom of the Layers panel. (Why a vector mask? Because the path you drew with the shape tool is vector-based, not pixel-based. As you learned on Opening an Existing Document, you can resize a vector anytime without losing quality by activating it and then using Free Transform [The Transformers]. For more on vector masks, skip ahead to Using Vector Masks.) Once you add the mask, Photoshop hides the photo’s boring, square edges.

Who knew that giving your photo rounded corners was so simple?

In addition to tools for selecting areas by shape, Photoshop has tools that let you select areas by color. This option is helpful when you want to select a chunk of an image that’s fairly uniform in color, like someone’s skin, the sky, or the paint job on a car. Photoshop has lots of tools to choose from, and in this section, you’ll learn how to pick the one that best suits your needs.

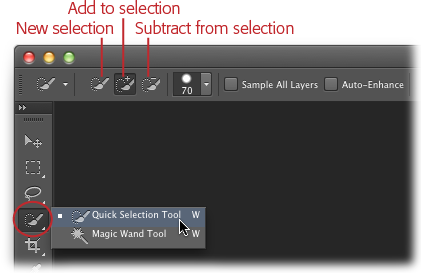

The Quick Selection tool is shockingly easy to use and lets you create complex selections with just a few brushstrokes. As you paint with this tool, your selection expands outward to encompass pixels similar in color to the ones you’re brushing across. It works insanely well if there’s a fair amount of contrast between what you want to select and everything else. This tool lives in the same toolset as the Magic Wand, as you can see in Figure 4-7.

Figure 4-7. You can press the W key to activate the Quick Selection tool. (To switch between it and the Magic Wand, press Shift-W.) When you activate the Quick Selection tool, the Options bar sports buttons that let you create a new selection as well as add to or subtract from the current selection.

To use this wonderfully friendly tool, click anywhere in the area you want to select or drag the brush cursor across it, as shown in Figure 4-8. When you do that, Photoshop thinks for a second and then creates a selection based on the color of the pixels you clicked or brushed across. The size of the area Photoshop selects is proportional to the size of the brush you’re using: A larger brush creates a larger selection. You adjust the Quick Selection tool’s brush size just like any other brush: by choosing a new size from the Brush picker in the Options bar, or by using the left and right bracket keys ([ and ]) to decrease and increase brush size (respectively). (Chapter 12 covers brushes in detail.) For the best results, use a hard-edged brush to produce well-defined edges (instead of the slightly transparent edges produced by a soft-edged brush) and turn on the Auto-Enhance setting shown in Figure 4-7 and discussed in the box on Smart Auto-Enhancing.

Figure 4-8. If the color of the objects you want to select differs greatly from the color of their background, like these chili peppers, use the Quick Selection tool. With this tool active, you can either click the area you want to select or drag your cursor (circled) across the area as if you were painting. As soon as you start painting with this tool, you see a tiny + sign inside the cursor (as shown here) and Photoshop puts the tool in “Add to selection” mode, which lets you add to an existing selection or make multiple selections.

When the Quick Selection tool is active, the Options bar includes these settings (see Figure 4-7):

New selection. When you first grab the Quick Selection tool, it’s set to this mode, which creates a brand-new selection when you click or drag (indicated by the tiny + sign that appears inside the cursor, as shown in Figure 4-8).

Add to selection. Once you’ve clicked or made an initial brushstroke, the Quick Selection tool automatically switches to this mode. Now Photoshop adds any areas you brush over or click to the current selection. If you don’t like the selection Photoshop has created and want to start over, press ⌘-Z (Ctrl+Z on a PC) to undo it, or click the Options bar’s “New selection” button and then brush across the area again. (The old selection disappears as soon as you start a new one.) To get rid of the marching ants altogether, choose Select→Deselect.

Subtract from selection. If Photoshop selected more than you wanted it to, click the “Subtract from selection” button (a tiny – sign appears in your cursor) and then simply paint across the area you don’t want selected to make Photoshop exclude it. You can also press and hold the Option key (Alt on a PC) to enter “Subtract from selection” mode.

Note

To get the most out of the Quick Selection tool, you’ll probably need to do a fair amount of adding to and subtracting from your selections. That said, you can change how picky this tool is by adjusting the Magic Wand’s Tolerance setting (sounds strange, but it’s true). Skip ahead to The Magic Wand Tool in the next section to learn how.

Brush Size/Hardness. Use a larger brush to select big areas and a smaller brush to select small or hard-to-reach areas. As explained earlier, you’ll get better results with this tool by using a hard-edged brush instead of a soft-edged one.

Sample All Layers. This setting is initially turned off, which means Photoshop examines only the pixels on the active layer (the one that’s highlighted in the Layers panel). If you turn on this setting, Photoshop examines the whole enchilada—everything in your document—and grabs all similar pixels no matter which layer they’re on.

Auto-Enhance. Because the Quick Selection tool makes selections extremely quickly, their edges can end up looking blocky and imperfect. Turn on this checkbox to tell Photoshop to take its time and think more carefully about the selections it makes. This feature gives your selections smoother edges, but if you’re working with a really big file, you could do your taxes while it’s processing. The box below has tips for using this feature.

The Magic Wand lets you select areas of color by clicking rather than dragging. It’s in the same toolset as the Quick Selection tool, and you can grab it by pressing Shift-W (it looks like a wizard’s wand, as shown back in Figure 4-7). The Magic Wand is great for selecting solid-colored backgrounds or large bodies of similar color, like a cloudless sky, with just a couple of clicks. (The Quick Selection tool is better at selecting objects.)

When you click once with the Magic Wand in the area you want to select, Photoshop magically (hence the name) selects all the pixels on the currently active layer that are both similar in color and touching one another (see The Magic Wand Tool to learn how to tweak this behavior). If the color in the area you want to select varies a bit, Photoshop may not select all of it. In that case, you can add to the selection either by pressing and holding the Shift key as you click nearby areas or by modifying the Magic Wand’s tolerance in the Options bar as described in a sec and shown in Figure 4-9. To subtract from the selection, just press and hold the Option key (Alt on a PC) while you click the area you don’t want included.

When you activate the Magic Wand, the Options bar includes these settings:

Sample Size. In CS6, this menu lets you change the way the Magic Wand calculates which pixels to select (in previous versions, you had to switch to the Eyedropper tool to see this menu). From the factory, it’s set to Point Sample, which makes the tool look only at the color of the specific pixel you clicked when determining its selection. However, the menu’s other options cause it to look at the original pixel and average it with the colors of surrounding pixels. For example, you can make the Magic Wand average the pixel you clicked plus the eight surrounding pixels by choosing “3 by 3 Average,” or as much as the surrounding 10,200 pixels by choosing “101 by 101 Average.” The “3 by 3 Average” setting works well for most images. If you need to select a really big area, you can experiment with one of the higher settings, like “31 by 31 Average.”

Figure 4-9. With its tolerance set to 32, the Magic Wand did a good job of selecting the sky behind downtown Dallas. You’ve got several ways to select the spots it missed, like the area circled at the bottom left: You can add to the selection by pressing the Shift key as you click in that area, increase the Tolerance setting in the Options bar and then click the sky again to create a brand-new selection, or skip to page 156 to learn how to expand the selection with the Grow and Similar commands. Give this selection technique a shot by downloading the practice file Dallas.jpg from this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds.

Tolerance. This setting controls both the Magic Wand’s and the Quick Selection tool’s sensitivity—how picky each tool is about which pixels it considers similar in color. If you increase this setting, the tool gets less picky (in other words, more tolerant) and selects every pixel that could possibly be described as similar to the one you clicked. If you decrease this setting, the tool gets pickier and selects only pixels that closely match the one you clicked.

Out of the box, the tolerance is set to 32, but it can go all the way up to 255. (If you set it to 0, Photoshop selects only pixels that exactly match the one you clicked; if you set it to 255, the program selects every color in the image.) It’s usually a good idea to keep the tolerance fairly low (somewhere between 12 and 32); you can always click an area to see what kind of selection you get, increase the tolerance if you need to, and then click that area again (or add to the selection using the Shift key, as described above).

Anti-alias. Leave this setting turned on to make Photoshop soften the edges of the selection ever so slightly. If you want a super-crisp edge, turn it off.

Contiguous. You’ll probably want to leave this checkbox turned on; it makes the Magic Wand select pixels that are adjacent to one another. If you turn it off, Photoshop goes hog wild and selects all similar-colored pixels no matter where they are.

Sample all layers. If your document has multiple layers and you leave this checkbox turned off, Photoshop examines only pixels on the active layer and ignores the other layers. If you turn this setting on, Photoshop examines the whole image and selects all pixels that are similar in color, no matter which layer they’re on.

Note

The Magic Wand is rather notorious for making the edges of selections jagged because it concentrates on selecting whole pixels, instead of partially transparent ones (this doesn’t happen as much with the Quick Selection tool). The fix is to click the Refine Edge button in the Options bar after you make the selection, and then adjust the Smooth slider in the resulting dialog box. Skip ahead to Modifying Selections to learn how.

Sometimes the Magic Wand makes a nearly perfect selection, leaving you with precious few pixels to add to it. If this happens, it simply means that the elusive pixels are just a little bit lighter or darker in color than what the Magic Wand’s tolerance setting allows for. You could Shift-click the elusive areas to add them to your selection, but the Select menu has a couple of options that can quickly expand the selection for you:

Choose Select→Grow to make Photoshop expand the selection to all similar-colored pixels adjacent to it (see Figure 4-10, top).

Choose Select→Similar to make Photoshop select similar-colored pixels throughout the whole image even if they’re not touching the original selection (see Figure 4-10, bottom).

Note

Because both of these commands base their calculations on the Magic Wand’s Tolerance setting (The Magic Wand Tool), you can adjust their sensitivity by adjusting that setting in the Options bar. You also can run these commands more than once to get the selection you want.

The Color Range command is similar to the tools in this section in that it makes selections based on colors, but it’s much better at selecting areas that contain lots of details (for example, the flower bunches in Figure 4-11). The Magic Wand tends to select solid pixels, whereas Color Range tends to select more transparent pixels than solid ones, resulting in softer edges. This fine-tuning lets Color Range produce selections with smoother edges (less blocky and jagged than the ones you get with the Magic Wand) and get in more tightly around areas with lots of details. As a bonus, you also get a handy preview in the Color Range dialog box, showing you which pixels it’ll select before you commit to the selection (unlike the Grow and Similar commands discussed in the previous section).

Figure 4-10. Top: Say you’re trying to select the red part of this Texas flag. After clicking once with the Magic Wand (with a Tolerance setting of 32), you still need to select a bit more of the red (left). Since the red pixels are all touching one another, you can run the Grow command a couple of times to make Photoshop expand your selection to include all the red (right). Bottom: If you want to select the red in these playing cards (what a poker hand!), the Grow command won’t help because the red pixels aren’t touching one another. In that case, click once with the Magic Wand to select one of the red areas (left) and then use the Similar command to grab the rest of them (right). Read ’em and weep, boys!

Tip

In Photoshop CS6, you can use the Color Range command’s new Skin Tones option to select people in your images. The box on Selecting Skin Tones and Faces has details.

Open the Color Range dialog box by choosing Select→Color Range, either before or after you make a selection. If you haven’t yet made a selection, Color Range examines the entire image. If you already have a selection, Photoshop looks only at the pixels within the selected area, which is helpful if you want to isolate a certain area. For example, you could throw a quick selection around the red flower in the center of Figure 4-11 and then use Color Range’s subtract-from-selection capabilities (explained in a moment) to carve out just the red petals. By contrast, if you want to use Color Range to help expand your current selection, press and hold the Shift key while you choose Select→Color Range.

Use the Select pop-up menu at the top of the Color Range dialog box to tell Photoshop which colors to include in the selection. The menu is automatically set to Sampled Colors, which lets you mouse over to the image (your cursor turns into a tiny eyedropper as shown in Figure 4-11) and click the color you want to select. If you change the Select menu’s setting to Reds, Blues, Greens, or whatever, Color Range will examine your image and grab that range of colors all by itself once you click OK.

If you’re trying to select adjacent pixels, turn on the Localized Color Clusters checkbox. When you do, the Range slider becomes active so you can tweak the range of colors Photoshop includes in the selection. Increase this setting and Photoshop includes more colors and makes larger selections; lower it and Photoshop creates a smaller selection because it gets pickier about matching colors.

Figure 4-11. The Color Range command is handy when you need to select an area with lots of details, like the red and blue petals of these flowers. The dialog box’s preview area shows which parts of the image Photoshop will select when you click OK (they’re displayed in white).

You can tweak the point at which Photoshop partially selects pixels by adjusting the Fuzziness setting. Its factory setting is 40, but you can set it to anything between 0 and 200. As you move the Fuzziness slider (or type a number in the text box), keep an eye on the dialog box’s preview area—the parts of the image that Photoshop will fully include in the selection appear white, and any pixels that are partially selected appear gray (see Figure 4-11).

Note

As mentioned in the box on Selecting the Opposite, it’s sometimes easier to select what you don’t want in order to get the selection you need. To use the Color Range dialog box to select what you don’t want, turn on its Invert checkbox.

Use the eyedroppers on the dialog box’s right side to add or subtract colors from your selection; the eyedropper with the tiny + sign adds to the selection, and the one with the – sign subtracts from it. (Use the plain eyedropper to make your initial selection.) When you click one of these eyedroppers, mouse over to your image, and then click the color you want to add or subtract, Photoshop updates the Color Range dialog box’s preview to show what the new selection looks like. It sometimes helps to keep the Fuzziness setting fairly low (around 50 or so) while you click repeatedly with the eyedropper.

Tip

You can use the radio buttons beneath the Color Range dialog box’s preview area to see either the selected area (displayed in white) or the image itself. But there’s a better, faster way to switch between the two views: With the Selection radio button turned on, press the ⌘ key (Ctrl on a PC) to temporarily switch to image preview. When you let go of the key, you’re back to selection preview.

The Selection Preview pop-up menu at the bottom of the dialog box lets you display a selection preview on the image itself so that, instead of using the dinky preview in the dialog box, you can see the proposed selection right on your image. But you’ll probably want to leave this menu set to None because the preview options that Photoshop offers (Grayscale, Black Matte, and so on) get really distracting!

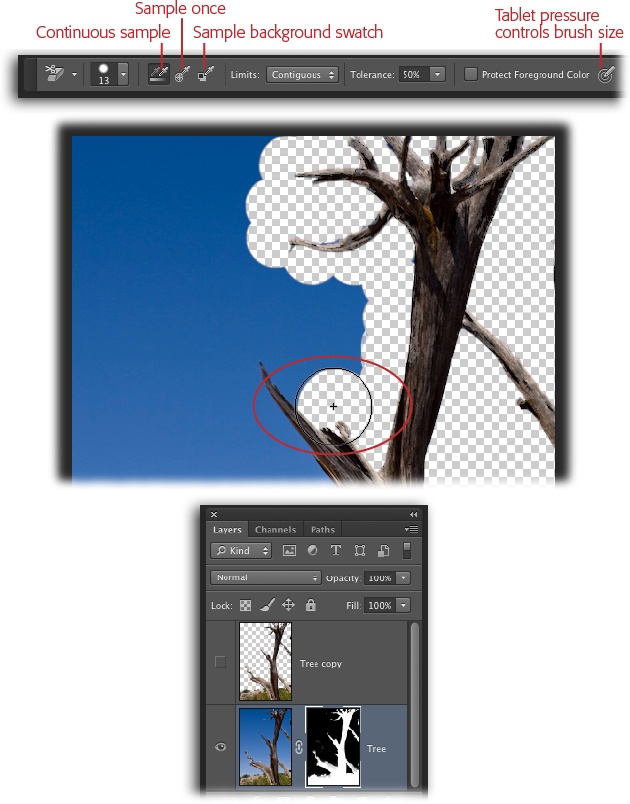

These two tools let you erase parts of an image based on the color under your cursor without having to create a selection first. You’re probably thinking, “Hey, I want to create a selection, not go around erasing stuff!” And you have a valid point except that, after you’ve done a little erasing, you can always load the erased area (or what’s left) as a selection. All you have to do is think ahead and create a duplicate layer before you start erasing, as this section explains.

Say you have an image with a strong contrast between the item you want to select and its background, like a dead tree against the sky. In that case, Photoshop has a couple of tools that can help you erase the sky super fast (see Figure 4-12). Sure, you could use the Magic Wand or Quick Selection tool to select the sky and then delete or mask it (Layer Blending), but the Background Eraser lets you erase more carefully around the edges of the tree.

Tip

The Eraser tool’s keyboard shortcut is the E key. To switch among the various eraser tools, press Shift-E repeatedly.

Figure 4-12. You may never see these tools because they’re hidden inside the same toolset as the regular Eraser tool. Just click and hold the Eraser tool’s icon until this little pop-up menu appears. Pick an eraser based on how you want to use it: You drag with the Background Eraser (as if you were painting, which is great for getting around the edges of an object), whereas you simply click with the Magic Eraser.

This tool lets you delete an image’s background by painting (dragging) across the pixels you want to delete. When you activate the Background Eraser, your cursor turns into a circle with tiny crosshairs in its center. The crosshairs cursor controls which pixels Photoshop deletes, so be extra careful that it touches only pixels you want to erase. Up in the Options bar, you can tweak the following settings (see Figure 4-13):

Brush Preset picker. This is where you choose the shape and size of your brush cursor. For best results, stick with a soft-edged brush. Just click the down-pointing triangle next to this menu to grab one.

Sampling. This setting is made up of three buttons whose icons all include eyedroppers. Sampling controls how often Photoshop looks at the color the crosshairs are touching to decide what to erase. If your image’s background has a lot of color variation, leave this set to Continuous so Photoshop keeps a constant watch on what color pixels the crosshairs are touching. But if the background’s color is fairly uniform, change this setting to Once; Photoshop then checks the color the crosshairs touch just once and resolves to erase only pixels that closely match it. If you’re dealing with an image where there’s only a small area for you to paint (like a tiny portion of sky showing through a lush tree), change this setting to Background Swatch, which tells Photoshop to erase only colors that are similar to your current background color chip (how similar they have to be is controlled by the Tolerance setting described in a sec). To choose the color, click the background color chip at the bottom of the Tools panel (Foreground and Background Color Chips), mouse over to your image, and then click an area that’s the color you want to erase.

Figure 4-13. Even though the Background Eraser is destructive (it erases pixels), you can use it in a nondestructive way by remembering to duplicate the soon-to-be-erased layer first. Then load the erased layer as a selection and use it as a layer mask on the original layer. As you can see here, Photoshop pays attention only to the color you touch with the crosshairs in the center of the cursor; even though the tree’s branches are within the brush area (circled), Photoshop deletes only the blue pixels. If you want to practice erasing this background, you can download DeadTree.jpg from this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds.

Limits. When you first launch Photoshop, this field is set to Contiguous, which means the tool erases only pixels adjacent to those you touch with the crosshairs. If you want to erase similar-colored pixels elsewhere in your image (for example, the background behind a really thick tree or a bunch of flowers), change this setting to Discontiguous. Find Edges erases only adjacent pixels, but it does so while preserving the sharpness of the object’s edge.

Tolerance. This setting works just like the Magic Wand’s Tolerance setting (The Magic Wand Tool): A lower number makes the tool pickier about the pixels it erases, and a higher number makes it less picky.

Protect Foreground Color. If you can’t seem to get the Tolerance setting high enough and you’re still erasing some of the area you want to keep, turning on this checkbox can help. When it’s on, you can tell Photoshop which area you want to keep (the foreground) by Option-clicking (Alt-clicking on a PC) that area. If the area you want to keep is a different color in different parts of your image, turn this setting off or Option-click (Alt-click) to resample the foreground area.

Here’s how to use the Background Eraser to remove the sky behind a dead tree without harming the original pixels, as shown in Figure 4-13:

Open a photo and double-click its Background layer to make it editable (Restacking Layers), duplicate the Background by pressing ⌘-J (Ctrl+J on a PC), and then hide the original Background layer.

Since you’ll add a layer mask to the original layer in the last step of this list, you need to unlock the Background to make it editable. And because you’ll do your erasing on the duplicate layer, you don’t need to see the original layer. Over in the Layers panel, click the little visibility eye to the left of the original layer’s thumbnail to turn it off.

Grab the Background Eraser tool and paint away the background.

This tool is in the same toolset as the Eraser tool (see Figure 4-12). Once you’ve activated it, mouse over to your document; your cursor morphs into a circle with tiny crosshairs in the center. Remember that the trick is to let the crosshairs touch only the pixels you want to erase (it doesn’t matter what the circle part of the cursor touches). If you need to, increase and decrease your brush cursor’s size by pressing the left and right bracket keys on your keyboard, respectively.

If the tool is erasing too much or too little of your image, tweak the Tolerance setting in the Options bar.

If an area in your image is almost the same color as the background, lower the tolerance to make the tool pickier about what it’s erasing so that it erases only pixels that closely match the ones you touch with the crosshairs. Likewise, if it’s not erasing enough of the background, raise the tolerance to make it zap more pixels.

Tip

It’s better to erase small sections at a time instead of painting around the entire object in one continuous stroke. Press your mouse button to erase some of the area around the object, let go of the button, click again to erase a little more, and so on. That way, if you need to undo your erasing with the History panel or the Undo command (⌘-Z; Ctrl+Z on a PC), you won’t have to watch all that erasing unravel before your eyes.

Once you get a clean outline around the object, switch to the regular Eraser tool or the Lasso tool (Lasso Tool) to get rid of the remaining background.

After you erase the hard part—the area around the edges—with the Background Eraser, you can use the regular Eraser tool, set to a large brush, to get rid of the remaining background quickly. Or you can use the Lasso tool to select the remaining areas and then press the Delete key (Backspace on a PC) to get rid of ’em.

Load the erased layer as a selection and turn off its visibility.

Over in the Layers panel, ⌘-click (Ctrl-click on a PC) the thumbnail of the layer you did the erasing work on to create a selection around the tree. When you see the marching ants, click the layer’s visibility eye to hide it.

Activate the original layer, turn on its visibility, and then add a layer mask to it.

In the Layers panel, click once to activate the original layer (the unlocked Background) and then click the area to the left of its thumbnail to make it visible again. While you have marching ants running around the newly erased area, add a layer mask (Layer Blending) to the original layer by clicking the circle-within-a-square icon at the bottom of the Layers panel.

You’re basically done at this point, but if you need to do any cleanup work (if the Background Eraser didn’t do a perfect job getting around the edges, say), now’s the time to edit the layer mask. To do so, click the mask’s thumbnail over in the Layers panel. Then press B to grab the Brush tool and set your foreground color chip to black (Foreground and Background Color Chips). Now, when you brush across your image, you’ll hide more of the sky. If you need to reveal more of the tree, set your foreground color chip to white, and then paint the area you want to reveal. (See Layer Blending for a detailed discussion of creating and editing layer masks.) Alternatively, you can use the Refine Edge dialog box to fine-tune your selection before adding the mask. Modifying Selections tells you how.

Sure, duplicating the layer you’re erasing adds an extra step, but that way you’re not deleting any pixels—you’re just hiding them with a layer mask, so you can get ’em back if you want to. How cool is that?

This tool works just like the Background Eraser except that, instead of a brush cursor that you paint with, it has a cursor that looks like a cross between the Eraser tool and the Magic Wand. Just as the Magic Wand can select color with a single click, the Magic Eraser can zap color with a single click, so it’s great for instantly erasing areas of solid color. Since this tool is an eraser, it really will delete pixels, so you’ll want to duplicate your Background layer before using it.

You can alter the Magic Eraser’s behavior by adjusting these Options bar settings:

Anti-alias. Turning this checkbox on makes Photoshop slightly soften the edges of what it erases.

Contiguous. To erase pixels that touch one another, leave this checkbox turned on. To erase similar-colored pixels no matter where they are in your image, turn it off.

Sample All Layers. If you have a multilayer document, turn on this checkbox to make Photoshop look at the pixels on all the layers instead of just the active layer.

Opacity. To control how strong the Magic Eraser is, you can enter a new value here. Out of the box, this option is set to 100, which removes 100 percent of the image, but you can enter 50 to make it wipe away 50 percent of the image’s color, for example.

As you might imagine, areas that aren’t uniform in shape or color can be a real bear to select. Luckily, Photoshop has a few tools in its arsenal to help you get the job done as easily as possible. In this section, you’ll learn about the three lassos and the Pen tool, as well as a few ways to use these tools together to select hard-to-grab spots.

The lasso toolset contains three freeform tools that let you draw an outline around the area you want to select. If you’ve got an amazingly steady mouse hand or if you use a graphics tablet (see the box on The Joy of Painter), you may fall in love with the plain ol’ Lasso tool. If you’re trying to select an object with a lot of straight edges, the Polygonal Lasso tool will do you proud. And the Magnetic Lasso tries to create a selection for you by examining the color of the pixels your cursor is over. The following sections explain all three tools, which share a slot near the top of the Tools panel (see Figure 4-14).

Figure 4-14. So many lassos, so little time! The regular Lasso tool is great for drawing a selection freehand, the Polygonal Lasso is good for drawing selections around shapes that have a lot of straight lines, and the Magnetic Lasso is like an automatic version of the regular Lasso—it tries to make the selection for you.

The regular Lasso tool lets you draw a selection completely freeform as if you were drawing with a pencil. To activate this tool, simply click it in the Tools panel (its icon looks like a tiny lasso—no surprise there) or press the L key. Then click in your document and drag to create a selection. Once you stop drawing and release the mouse button, Photoshop automatically completes the selection with a straight line (that is, if you don’t complete it yourself by mousing back over your start point) and you see marching ants.

Tip

It’s nearly impossible to draw a straight line with the Lasso tool, unless you’ve got the steady hand of a surgeon. But if you press and hold the Option key (Alt on a PC) and then release your mouse button, you’ll temporarily switch to the Polygonal Lasso tool so you can draw a straight line (see the next section). When you release the Option (Alt) key, Photoshop completes your selection with a straight line.

The Options bar (shown in Figure 4-14) sports the same settings whether you have the Lasso tool or the Polygonal Lasso tool active. Here’s what it offers:

Mode. These four buttons (whose icons look like pieces of paper and are labeled in Figure 4-14) let you choose among the same modes you get for most of the selection tools: New, “Add to selection,” “Subtract from selection,” and “Intersect with selection.” They’re discussed in detail back on pages 143–144.

Feather. If you want Photoshop to soften the edges of your selection, enter a pixel value in this field. Otherwise, the selection will have a hard edge. (See the box on The Softer Side of Selections for more on feathering.)

Anti-alias. If you leave this setting turned on, Photoshop slightly blurs the edges of your selection, making them less jagged—The Rectangular and Elliptical Marquee Tools has the details.

If your image has a lot of straight lines in it (like the star in Figure 4-15), the Polygonal Lasso tool is your ticket. Instead of letting you draw a selection that’s any shape at all, the Polygonal Lasso draws only straight lines. To use it, click once to set the starting point, and move your cursor along the shape of the item you want to select; click again where the angle changes; and then repeat this process until you’ve outlined the whole shape. It’s super simple to use, as Figure 4-15 illustrates. To close your selection, point your cursor at the first point you created. When a tiny circle appears below your cursor (it looks like a degree symbol), click once to close the selection and summon the marching ants.

This tool has all the power of the other lasso tools, except that it’s smart—or at least it tries to be! Click once to set a starting point, and from there the Magnetic Lasso tries to guess what you want to select by examining the colors of the pixels your cursor is over (you don’t even need to hold your mouse button down). As you move your cursor over the edges you want to select, it sets additional anchor points for you (anchor points are fastening points that latch onto the path you’re tracing; they look like tiny, see-through squares). To close the selection, put the cursor above your starting point. When a tiny circle appears below the cursor, click once to close the selection and summon the marching ants (or close the selection with a straight line by triple-clicking).

As you might imagine, the Magnetic Lasso tool works best when there’s strong contrast between the item you want to select and the area around it (see Figure 4-16). However, if you reach an area that doesn’t have much contrast—or a sharp corner—you can give the tool a little nudge by clicking to set a few anchor points of your own. If it goes astray and sets an erroneous anchor point, tap the Delete key (Backspace on a PC) to get rid of the point and then click to set more anchor points until you reach an area of greater contrast where the tool can be trusted to set its own points.

Figure 4-16. If you’re trying to select an object on a plain, high-contrast background, the Magnetic Lasso works great because it can easily find the edge of the object. For best results, glide your cursor slowly around the edge of the item you want to select (you don’t need to hold your mouse button down). To draw a straight line, temporarily switch to the Polygonal Lasso tool by Option-clicking (Alt-clicking on a PC) where you want the line to start and then clicking where you want it to end. Photoshop then switches back to the Magnetic Lasso, and you’re free to continue gliding around the rest of the object’s edges.

Tip

If you’re not crazy about the Magnetic Lasso’s cursor (which looks like a triangle and a horseshoe magnet), press the Caps Lock key and it changes to a brush cursor with crosshairs at its center. Press Caps Lock again to switch back to the standard cursor. Alternatively, you can use Photoshop’s preferences to change it to a precise cursor; Controlling the Brush Cursor’s Appearance explains how.

You can get better results with this tool by adjusting its Options bar settings (shown in Figure 4-16). Besides the usual suspects like selection mode, feather, and anti-alias settings (all discussed on The Rectangular and Elliptical Marquee Tools), the Magnetic Lasso also lets you adjust the following:

Width determines how close your cursor needs to be to an edge for the Magnetic Lasso to select it. Out of the box, this field is set to 10 pixels, but you can enter a value between 1 and 256. Use a lower number when you’re trying to select an area whose edge has a lot of twists and turns and a higher number for an area with fairly smooth edges. For example, to select the yellow rose in Figure 4-16, you’d use a higher setting around the petals and a lower setting around the leaves because they’re so jagged.

Contrast controls how much color difference there needs to be between neighboring pixels before the Magnetic Lasso recognizes it as an edge. You can try increasing this percentage when you want to select an edge that isn’t well defined, but you might have better luck with a different selection tool. If you’re a fan of keyboard shortcuts—and you haven’t started drawing a selection—press the comma (,) or period (.) key to decrease or increase this setting in 1 percent increments, respectively; add the Shift key to these keyboard shortcuts to set it to 1 percent or 100 percent, respectively.

Frequency determines how many anchor points the tool lays down. If you’re selecting an area with lots of details, you’ll need more anchor points than for a smooth area. Setting this field to 0 makes Photoshop add very few points, and 100 makes it have a point party. The factory setting—57—usually works just fine. Before you draw a selection, you can press the semicolon (;) or apostrophe (’) key to decrease or increase this setting by 3, respectively; add the Shift key to these keyboard shortcuts to jump between 1 and 100.

Use tablet pressure to change pen width. If you have a pressure-sensitive graphics tablet, turning on this setting—whose button looks like a pen tip with circles around it—lets you override the Width setting by pressing harder or softer on your tablet with the stylus. (The box on The Joy of Painter has more about graphics tablets.)

Another great way to select an irregular object or area is to trace its outline with the Pen tool. Technically, you don’t draw a selection with this method; you draw a path (Drawing Paths with the Pen Tool), which you can then load as a selection or use to create a vector mask (Making Selections and Masks with Paths). This technique requires quite a bit of skill because the Pen tool isn’t your average, everyday, well…pen, but it’ll produce the smoothest-edged selections this side of the Rio Grande. Head on over to Chapter 13 to read all about it.

As you’ll learn in Chapter 5, the images you see onscreen are made up of various colors. In Photoshop, each color is stored in its own channel (which is kind of like a layer) that you can view and manipulate. If the object or area you’re trying to select is one that you can isolate in a channel, you can load that channel as a selection with a click of your mouse. Chapter 5 discusses this incredibly useful technique in detail, starting on Selecting Objects with Channels.

As wonderful as the aforementioned selection tools are individually, they’re much more powerful if you use them together.

Remember how every tool discussed so far has an “Add to selection” and “Subtract from selection” mode? This means that, no matter which tool you start with, you can add to—or subtract from—the active selection with a completely different tool. Check out Figure 4-17, which gives you a couple of ideas for using the selection tools together. And thanks to the spring-loaded tools feature (see the Tip on Tip), switching between tools is a snap.

Figure 4-17. Top: It’s worth taking a moment to try to see the shapes that make up the area you want to select. For example, you can select the circular top of this famous Texas building (shown in red) using the Elliptical Marquee, and then switch to the Rectangular Marquee set to “Add to selection” mode to select the area shown in green. Bottom: Another way to use the selection tools together is to draw a rectangular selection around the object you want to select, and then switch to the Magic Wand to subtract the areas you don’t want. Hold down the Option key (Alt on a PC) so you’re in “Subtract from selection” mode and then click the areas you don’t want included in your selection, like this grayish background. With just a couple of clicks, you can select the prickly pear shown here.

As you can see, there are a gazillion ways to create selections, though any selection you make will likely need tweaking no matter which method you use. The next section is all about perfecting selections.

Note

You can also paint selections onto your image by using Quick Mask mode, which is discussed in the next section on Using Quick Mask Mode.

The difference between a pretty-good-around-the-edges selection and a perfect one is what separates Photoshop pros from mere dabblers. As you’re about to learn, there are a bunch of ways to modify, reshape, and even save selections, all of which are explained in the following pages.

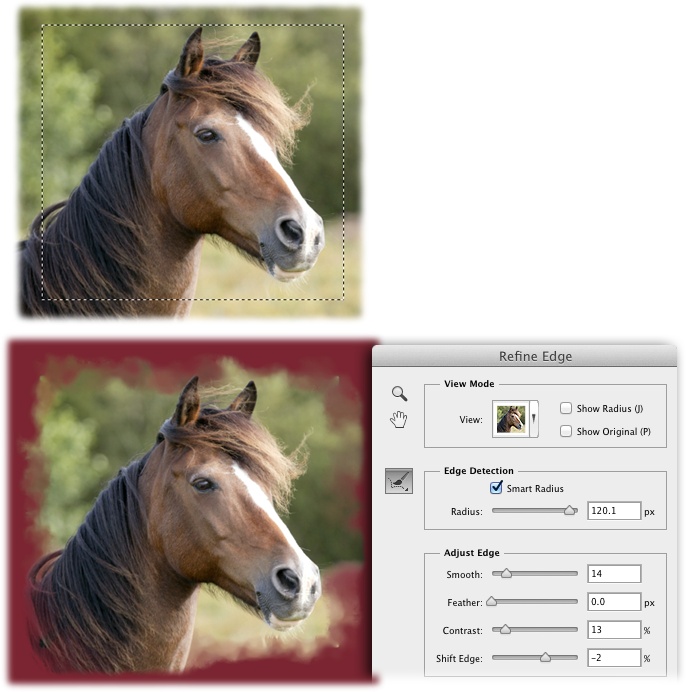

The best selection modifier in town is the Refine Edge dialog box (Figure 4-18), which is great for selecting the tough stuff like hair and fur. It combines several edge-adjustment tools that used to be scattered throughout Photoshop’s menus and includes an extremely useful preview option.

Anytime you have a selection tool active and some marching ants on your screen, you’ll see the Refine Edge button sitting pretty up in the Options bar; simply click it to open the dialog box. You can also open it by choosing Select→Refine Edge, pressing Option-⌘-R (Alt+Ctrl+R on a PC), or by clicking the Properties panel’s Mask Edge button (see Figure 3-29 on page 123).

The Refine Edge dialog box gives you seven different ways to preview your selection. Because the preview appears in the main document window, you’ll want to move the Refine Edge dialog box aside so it’s not covering your image. Depending on the colors in your image, one of these View modes will let you see the selection better than the rest:

Marching Ants. This view just shows the selection on the image itself. Keyboard shortcut: M.

Overlay. As the name indicates, this view displays your selection overlaid with the Quick Mask (Using Quick Mask Mode) which, unless you’ve changed its color, is light red. (To change that color, see the box on Changing Quick Mask’s Color.) Because the red overlay is see-through, it’s the best choice when your selection will include hair or fur that isn’t included in the selection just yet. Keyboard shortcut: V.

Tip

You can cycle through the preview modes by pressing the F key repeatedly when you have the Refine Edge dialog box open. To temporarily see your original image, press the X key; press X again to go back to the View mode you were using.

Figure 4-18. The Refine Edge dialog box not only lets you see a live, continuously updated preview of what your selection will look like after fine-tuning, but you also get seven different views to choose from, along with two tools you can use to refine your selection before you click OK (Overlay is particularly handy if you’re dealing with hair or fur). If you forget what the dialog box’s various settings do, never fear: Just point your cursor at a setting, and a tooltip appears explaining what that item does.

On Black. This view displays the selection on a black background, which is helpful if your image is light colored and doesn’t have a lot of black in it. Keyboard shortcut: B.

On White. Choose this view if your image is mostly dark. The stark white background makes it easy to see your selection and the object you’re selecting while you’re fine-tuning it using the dialog box’s settings. Keyboard shortcut: W.

Black & White. This view displays your selection as an alpha channel (Multichannel Mode). Photoshop makes your selection white and the mask black; transitions between the two areas are subtle shades of gray. The gray areas let you see how detailed your mask is, so you’ll spend a fair amount of time in this mode. Keyboard shortcut: K.

On Layers. To see your selection atop the gray-and-white transparency checkerboard, choose this mode. Keyboard shortcut: L.

Reveal Layer. This mode displays your image without a selection. Keyboard shortcut: R.

Once you’ve chosen a View mode, you can tweak the following settings (and for best results, Adobe suggests you adjust them in this order):

Smart Radius. Turn this checkbox on to make Photoshop look closely at the edges of your selection to determine whether they’re hard (like the outline of your subject’s body) or soft (like your subject’s hair or fur). It’s a good idea to turn this setting on each time you open the Refine Edge dialog box. (If you turn on the Remember Settings option at the bottom of the dialog box, Smart Radius will stay on until you turn it off.)

Radius. This setting controls the size of the area affected by the settings in this dialog box—in other words, how far beyond the edge of your selection Photoshop looks when it’s refining that edge. You can think of this setting as the selection’s degree of difficulty. For example, if your selection is really complex, like the horse’s mane in Figure 4-19, increase this setting to make Photoshop look beyond the original selection boundary for all the wispy stuff (which also makes the program slightly soften the selection’s edge). If your selection is fairly simple, lower this setting so Photoshop analyzes just the selection’s boundary, which creates a harder edge. There are no magic numbers for this setting—it varies from image to image—so you’ll need to experiment in order to get your selection just right.

Refine Radius tool. Once you’ve turned on Smart Radius, you can use this tool (shown in Figure 4-18) to paint over the edges of your selection to make Photoshop fine-tune them even more in particular spots (see Figure 4-19, top). This is where the Refine Edge dialog box really works its magic: As you drag with this tool’s brush cursor, you can extend your selection beyond its original boundaries, creating a more precise selection of extremely fine details. This tool is also intuitive: As you brush across the edges of your selection, it pays attention and tries to learn how you want it to behave.

Erase Refinements tool. If Photoshop gets a little overzealous and includes too much of the background in your selection as you drag with the Refine Radius tool, use this tool to drag across the areas you don’t want to include in the selection.

Smooth. Increasing this setting makes Photoshop smooth the selection’s edges so they’re less jagged, but increasing it too much can make you lose details (especially on selections of things like hair). To bring back some details without decreasing this setting, try increasing the Radius and Contrast settings.

Feather. This setting controls how much Photoshop softens the edges of your selection, which is useful when you’re combining images, as discussed in the box on The Softer Side of Selections.

Contrast. This setting sharpens your selection’s edge, even if you softened it by increasing the Radius setting mentioned above. A higher number here creates a sharper edge and can actually reduce the noisy or grainy look that’s sometimes caused by a high Radius setting. (If you spend some quality time with Smart Radius and its refinement tools, you probably won’t use this slider much, if at all.)

Figure 4-19. Top: After creating a rough selection with the Quick Selection tool, you can use the Refine Edge dialog box’s Refine Radius tool to brush across areas you want to add to your selection. Bottom: Within minutes, you can settle this mare onto a new background, as shown here. What horse wouldn’t be happier hanging out on a field of bluebonnets? To try this yourself, trot on over to this book’s Missing CD page at www.missingmanuals.com/cds and download the file Horse.zip.

Shift Edge. You can tighten your selection (make it smaller) by dragging this slider to the left, which is a good idea if you’re dealing with hair or fur. To expand your selection and grab pixels you missed when you made the initial selection, drag this slider to the right.

Decontaminate Colors. This option helps reduce edge halos: leftover colored pixels around the edges of a selection that you see only after you put the object on a new background (as shown on Creating a Border Selection). Once you turn this checkbox on, Photoshop tries to replace the color of selected pixels with the color of pixels nearby (whether they’re selected or not). Drag the Amount slider to the right to change the color of more edge pixels, or to the left to change fewer. To see the color changes for yourself, choose Reveal Layer from the View menu near the top of the dialog box (or just press R).

Output To. This setting lets you tell Photoshop what you’d like it to do with your new and improved selection. Here are your options:

Selection adjusts your original selection, leaving you with marching ants on your original layer just like you started with.

Layer Mask adds a layer mask to the current layer according to the selection you just made. You’ll choose this option most of the time.

New Layer deletes the background and creates a new layer containing only the selected item, with no marching ants.

New Layer with Layer Mask adds a new layer complete with layer mask.

New Document deletes the background and sends only the selected item to a brand-new document.

New Document with Layer Mask sends the selected item to a new document complete with editable layer mask.

Whew! Those settings probably won’t make a whole lot of sense until you start using ’em. To get you off and running, here’s how to select a subject with wispy hair, like the horse in Figure 4-19:

Open an image and select the item using the Quick Selection tool.

Press W to grab the Quick Selection tool and paint across the object you want to select (Figure 4-19, top left). Don’t worry too much about the quality of the selection, because you’ll tweak it in a moment.

Open the Refine Edge dialog box.

Hop up to the Options bar and click the Refine Edge button.

Choose Overlay as your View mode.

To see the horse’s mane better—in all its wispy goodness—press V to view it with a red overlay.

Turn on the Smart Radius checkbox and drag the Radius slider to the right.

How far you should drag the Radius slider depends on your image. Your goal is to drag the slider as far to the right as you can while still maintaining some hardness in the selection’s edges. There’s no magic Radius setting that’ll work on every selection (a setting of 3.2 was used in Figure 4-19); it varies with every image. You won’t see anything change in your image right away when you tweak this setting, though a tiny rotating circle at the bottom left of the dialog box indicates that Photoshop is rethinking the selection.

Use the Refine Radius tool to brush across the soft edges of your selection (Figure 4-19, top right).

Press E to grab the Refine Radius tool, or click its icon near the top left of the Refine Edge dialog box (it looks like a tiny brush atop a curved, dotted line). Then mouse over to your image and brush across the soft areas you want to add to your selection, like the wispy bits of the horse’s mane. Try to avoid any areas that are correctly selected (such as the horse’s nose), as Photoshop tends to overanalyze them and exclude parts it shouldn’t. If you end up adding too much to the selection, press Option (Alt) to switch to the Eraser Refinement tool and then brush across the areas you don’t want selected.

Turn on the Decontaminate Colors checkbox and adjust the Amount slider.

Turn on the checkbox and then drag the slider slightly to the right to shift the color of partially selected edge pixels so they more closely match pixels that are fully selected. Once again, this value varies from image to image (15 percent was used for Figure 4-19).

From the Output To pop-up menu, chose “New Layer with Mask.”

Photoshop adds a layer mask to the active layer reflecting your selection, as shown in the Layers panel in Figure 4-19 (bottom).

Exhausted yet? This kind of thing isn’t easy, but once you master using Refine Edges, you’ll be able to create precise selections of darn near anything!

You can also use the Refine Edge dialog box to add creative edges to photos. For example, grab the Rectangular Marquee tool and draw a box around an image about half an inch inside the document’s edges (Figure 4-20, top). Then click the Options bar’s Refine Edge button and, in the resulting dialog box, drag the Radius slider to the right for a cool, painterly effect (how far you drag it is up to you). Be sure to choose Layer Mask from the dialog box’s Output To menu before you click OK to keep from harming your original image.

When you’re making selections, you may encounter edge halos (also called fringing or matting). An edge halo is a tiny portion of the background that stubbornly remains even after you try to delete it (or hide it with a layer mask, Layer Blending). They usually show up after you replace the original background with something new (see Figure 4-21).

Here are a few ways to fix edge halos:

Contract your selection. Use the Refine Edge dialog box (Modifying Selections) or choose Select→Modify→Contract to contract the selection (though the latter method won’t give you a preview). Use this technique while you still have marching ants—in other words, before you delete the old background (or, better yet, hide the background with a layer mask [Layer Blending]).

Run the Minimum filter on a layer mask. Once you’ve hidden an image’s background with a layer mask, you can run the Minimum filter on the mask to tighten it around the object. Other explains this super-useful trick. This is an excellent quick fix to have in your bag of Photoshop tricks.