Chapter 7. The Blockchain

Introduction

The blockchain data structure is an ordered, back-linked list of blocks of transactions. The blockchain can be stored as a flat file, or in a simple database. The Bitcoin Core client stores the blockchain metadata using Google’s LevelDB database. Blocks are linked “back,” each referring to the previous block in the chain. The blockchain is often visualized as a vertical stack, with blocks layered on top of each other and the first block serving as the foundation of the stack. The visualization of blocks stacked on top of each other results in the use of terms such as “height” to refer to the distance from the first block, and “top” or “tip” to refer to the most recently added block.

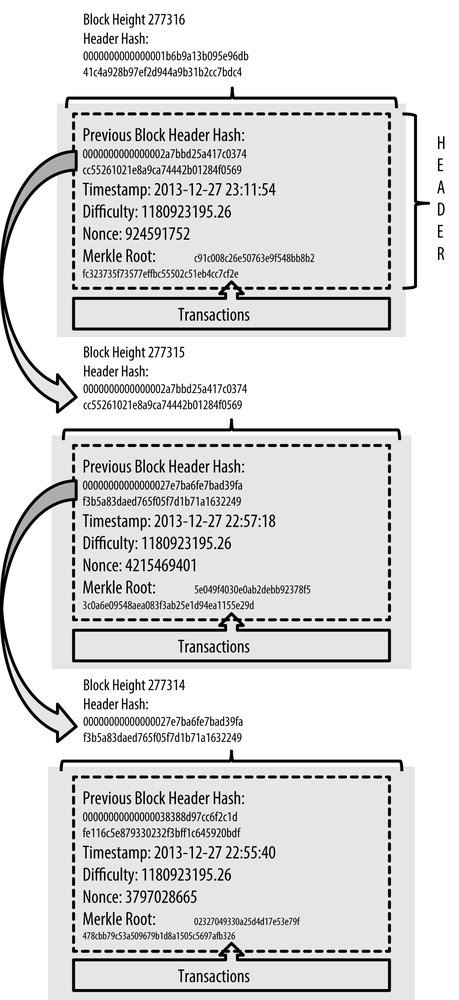

Each block within the blockchain is identified by a hash, generated using the SHA256 cryptographic hash algorithm on the header of the block. Each block also references a previous block, known as the parent block, through the “previous block hash” field in the block header. In other words, each block contains the hash of its parent inside its own header. The sequence of hashes linking each block to its parent creates a chain going back all the way to the first block ever created, known as the genesis block.

Although a block has just one parent, it can temporarily have multiple children. Each of the children refers to the same block as its parent and contains the same (parent) hash in the “previous block hash” field. Multiple children arise during a blockchain “fork,” a temporary situation that occurs when different blocks are discovered almost simultaneously by different miners (see Blockchain Forks). Eventually, only one child block becomes part of the blockchain and the “fork” is resolved. Even though a block may have more than one child, each block can have only one parent. This is because a block has one single “previous block hash” field referencing its single parent.

The “previous block hash” field is inside the block header and thereby affects the current block’s hash. The child’s own identity changes if the parent’s identity changes. When the parent is modified in any way, the parent’s hash changes. The parent’s changed hash necessitates a change in the “previous block hash” pointer of the child. This in turn causes the child’s hash to change, which requires a change in the pointer of the grandchild, which in turn changes the grandchild, and so on. This cascade effect ensures that once a block has many generations following it, it cannot be changed without forcing a recalculation of all subsequent blocks. Because such a recalculation would require enormous computation, the existence of a long chain of blocks makes the blockchain’s deep history immutable, which is a key feature of bitcoin’s security.

One way to think about the blockchain is like layers in a geological formation, or glacier core sample. The surface layers might change with the seasons, or even be blown away before they have time to settle. But once you go a few inches deep, geological layers become more and more stable. By the time you look a few hundred feet down, you are looking at a snapshot of the past that has remained undisturbed for millions of years. In the blockchain, the most recent few blocks might be revised if there is a chain recalculation due to a fork. The top six blocks are like a few inches of topsoil. But once you go more deeply into the blockchain, beyond six blocks, blocks are less and less likely to change. After 100 blocks back there is so much stability that the coinbase transaction—the transaction containing newly mined bitcoins—can be spent. A few thousand blocks back (a month) and the blockchain is settled history, for all practical purposes. While the protocol always allows a chain to be undone by a longer chain and while the possibility of any block being reversed always exists, the probability of such an event decreases as time passes until it becomes infinitesimal.

Structure of a Block

A block is a container data structure that aggregates transactions for inclusion in the public ledger, the blockchain. The block is made of a header, containing metadata, followed by a long list of transactions that make up the bulk of its size. The block header is 80 bytes, whereas the average transaction is at least 250 bytes and the average block contains more than 500 transactions. A complete block, with all transactions, is therefore 1,000 times larger than the block header. Table 7-1 describes the structure of a block.

| Size | Field | Description |

4 bytes | Block Size | The size of the block, in bytes, following this field |

80 bytes | Block Header | Several fields form the block header |

1-9 bytes (VarInt) | Transaction Counter | How many transactions follow |

Variable | Transactions | The transactions recorded in this block |

Block Header

The block header consists of three sets of block metadata. First, there is a reference to a previous block hash, which connects this block to the previous block in the blockchain. The second set of metadata, namely the difficulty, timestamp, and nonce, relate to the mining competition, as detailed in Chapter 8. The third piece of metadata is the merkle tree root, a data structure used to efficiently summarize all the transactions in the block. Table 7-2 describes the structure of a block header.

| Size | Field | Description |

4 bytes | Version | A version number to track software/protocol upgrades |

32 bytes | Previous Block Hash | A reference to the hash of the previous (parent) block in the chain |

32 bytes | Merkle Root | A hash of the root of the merkle tree of this block’s transactions |

4 bytes | Timestamp | The approximate creation time of this block (seconds from Unix Epoch) |

4 bytes | Difficulty Target | The proof-of-work algorithm difficulty target for this block |

4 bytes | Nonce | A counter used for the proof-of-work algorithm |

The nonce, difficulty target, and timestamp are used in the mining process and will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 8.

Block Identifiers: Block Header Hash and Block Height

The primary identifier of a block is its cryptographic hash, a digital fingerprint, made by hashing the block header twice through the SHA256 algorithm. The resulting 32-byte hash is called the block hash but is more accurately the block header hash, because only the block header is used to compute it. For example, 000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f is the block hash of the first bitcoin block ever created. The block hash identifies a block uniquely and unambiguously and can be independently derived by any node by simply hashing the block header.

Note that the block hash is not actually included inside the block’s data structure, neither when the block is transmitted on the network, nor when it is stored on a node’s persistence storage as part of the blockchain. Instead, the block’s hash is computed by each node as the block is received from the network. The block hash might be stored in a separate database table as part of the block’s metadata, to facilitate indexing and faster retrieval of blocks from disk.

A second way to identify a block is by its position in the blockchain, called the block height. The first block ever created is at block height 0 (zero) and is the same block that was previously referenced by the following block hash 000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f. A block can thus be identified two ways: by referencing the block hash or by referencing the block height. Each subsequent block added “on top” of that first block is one position “higher” in the blockchain, like boxes stacked one on top of the other. The block height on January 1, 2014, was approximately 278,000, meaning there were 278,000 blocks stacked on top of the first block created in January 2009.

Unlike the block hash, the block height is not a unique identifier. Although a single block will always have a specific and invariant block height, the reverse is not true—the block height does not always identify a single block. Two or more blocks might have the same block height, competing for the same position in the blockchain. This scenario is discussed in detail in the section Blockchain Forks. The block height is also not a part of the block’s data structure; it is not stored within the block. Each node dynamically identifies a block’s position (height) in the blockchain when it is received from the bitcoin network. The block height might also be stored as metadata in an indexed database table for faster retrieval.

Tip

A block’s block hash always identifies a single block uniquely. A block also always has a specific block height. However, it is not always the case that a specific block height can identify a single block. Rather, two or more blocks might compete for a single position in the blockchain.

The Genesis Block

The first block in the blockchain is called the genesis block and was created in 2009. It is the common ancestor of all the blocks in the blockchain, meaning that if you start at any block and follow the chain backward in time, you will eventually arrive at the genesis block.

Every node always starts with a blockchain of at least one block because the genesis block is statically encoded within the bitcoin client software, such that it cannot be altered. Every node always “knows” the genesis block’s hash and structure, the fixed time it was created, and even the single transaction within. Thus, every node has the starting point for the blockchain, a secure “root” from which to build a trusted blockchain.

See the statically encoded genesis block inside the Bitcoin Core client, in chainparams.cpp.

The following identifier hash belongs to the genesis block:

000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f

You can search for that block hash in any block explorer website, such as blockchain.info, and you will find a page describing the contents of this block, with a URL containing that hash:

https://blockchain.info/block/000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f

https://blockexplorer.com/block/000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f

Using the Bitcoin Core reference client on the command line:

$ bitcoind getblock 000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f

{"hash":"000000000019d6689c085ae165831e934ff763ae46a2a6c172b3f1b60a8ce26f","confirmations":308321,"size":285,"height":0,"version":1,"merkleroot":"4a5e1e4baab89f3a32518a88c31bc87f618f76673e2cc77ab2127b7afdeda33b","tx":["4a5e1e4baab89f3a32518a88c31bc87f618f76673e2cc77ab2127b7afdeda33b"],"time":1231006505,"nonce":2083236893,"bits":"1d00ffff","difficulty":1.00000000,"nextblockhash":"00000000839a8e6886ab5951d76f411475428afc90947ee320161bbf18eb6048"}

The genesis block contains a hidden message within it. The coinbase transaction input contains the text “The Times 03/Jan/2009 Chancellor on brink of second bailout for banks.” This message was intended to offer proof of the earliest date this block was created, by referencing the headline of the British newspaper The Times. It also serves as a tongue-in-cheek reminder of the importance of an independent monetary system, with bitcoin’s launch occurring at the same time as an unprecedented worldwide monetary crisis. The message was embedded in the first block by Satoshi Nakamoto, bitcoin’s creator.

Linking Blocks in the Blockchain

Bitcoin full nodes maintain a local copy of the blockchain, starting at the genesis block. The local copy of the blockchain is constantly updated as new blocks are found and used to extend the chain. As a node receives incoming blocks from the network, it will validate these blocks and then link them to the existing blockchain. To establish a link, a node will examine the incoming block header and look for the “previous block hash.”

Let’s assume, for example, that a node has 277,314 blocks in the local copy of the blockchain. The last block the node knows about is block 277,314, with a block header hash of 00000000000000027e7ba6fe7bad39faf3b5a83daed765f05f7d1b71a1632249.

The bitcoin node then receives a new block from the network, which it parses as follows:

{"size":43560,"version":2,"previousblockhash":"00000000000000027e7ba6fe7bad39faf3b5a83daed765f05f7d1b71a1632249","merkleroot":"5e049f4030e0ab2debb92378f53c0a6e09548aea083f3ab25e1d94ea1155e29d","time":1388185038,"difficulty":1180923195.25802612,"nonce":4215469401,"tx":["257e7497fb8bc68421eb2c7b699dbab234831600e7352f0d9e6522c7cf3f6c77",#[...manymoretransactionsomitted...]"05cfd38f6ae6aa83674cc99e4d75a1458c165b7ab84725eda41d018a09176634"]}

Looking at this new block, the node finds the previousblockhash field, which contains the hash of its parent block. It is a hash known to the node, that of the last block on the chain at height 277,314. Therefore, this new block is a child of the last block on the chain and extends the existing blockchain. The node adds this new block to the end of the chain, making the blockchain longer with a new height of 277,315. Figure 7-1 shows the chain of three blocks, linked by references in the previousblockhash field.

Merkle Trees

Each block in the bitcoin blockchain contains a summary of all the transactions in the block, using a merkle tree.

A merkle tree, also known as a binary hash tree, is a data structure used for efficiently summarizing and verifying the integrity of large sets of data. Merkle trees are binary trees containing cryptographic hashes. The term “tree” is used in computer science to describe a branching data structure, but these trees are usually displayed upside down with the “root” at the top and the “leaves” at the bottom of a diagram, as you will see in the examples that follow.

Merkle trees are used in bitcoin to summarize all the transactions in a block, producing an overall digital fingerprint of the entire set of transactions, providing a very efficient process to verify whether a transaction is included in a block. A Merkle tree is constructed by recursively hashing pairs of nodes until there is only one hash, called the root, or merkle root. The cryptographic hash algorithm used in bitcoin’s merkle trees is SHA256 applied twice, also known as double-SHA256.

When N data elements are hashed and summarized in a merkle tree, you can check to see if any one data element is included in the tree with at most 2*log2(N) calculations, making this a very efficient data structure.

The merkle tree is constructed bottom-up. In the following example, we start with four transactions, A, B, C and D, which form the leaves of the Merkle tree, as shown in Figure 7-2. The transactions are not stored in the merkle tree; rather, their data is hashed and the resulting hash is stored in each leaf node as HA, HB, HC, and HD:

H~A~ = SHA256(SHA256(Transaction A))

Consecutive pairs of leaf nodes are then summarized in a parent node, by concatenating the two hashes and hashing them together. For example, to construct the parent node HAB, the two 32-byte hashes of the children are concatenated to create a 64-byte string. That string is then double-hashed to produce the parent node’s hash:

H~AB~ = SHA256(SHA256(H~A~ + H~B~))

The process continues until there is only one node at the top, the node known as the Merkle root. That 32-byte hash is stored in the block header and summarizes all the data in all four transactions.

Because the merkle tree is a binary tree, it needs an even number of leaf nodes. If there is an odd number of transactions to summarize, the last transaction hash will be duplicated to create an even number of leaf nodes, also known as a balanced tree. This is shown in Figure 7-3, where transaction C is duplicated.

The same method for constructing a tree from four transactions can be generalized to construct trees of any size. In bitcoin it is common to have several hundred to more than a thousand transactions in a single block, which are summarized in exactly the same way, producing just 32 bytes of data as the single merkle root. In Figure 7-4, you will see a tree built from 16 transactions. Note that although the root looks bigger than the leaf nodes in the diagram, it is the exact same size, just 32 bytes. Whether there is one transaction or a hundred thousand transactions in the block, the merkle root always summarizes them into 32 bytes.

To prove that a specific transaction is included in a block, a node only needs to produce log2(N) 32-byte hashes, constituting an authentication path or merkle path connecting the specific transaction to the root of the tree. This is especially important as the number of transactions increases, because the base-2 logarithm of the number of transactions increases much more slowly. This allows bitcoin nodes to efficiently produce paths of 10 or 12 hashes (320–384 bytes), which can provide proof of a single transaction out of more than a thousand transactions in a megabyte-size block.

In Figure 7-5, a node can prove that a transaction K is included in the block by producing a merkle path that is only four 32-byte hashes long (128 bytes total). The path consists of the four hashes (noted in blue in Figure 7-5) HL, HIJ, HMNOP and HABCDEFGH. With those four hashes provided as an authentication path, any node can prove that HK (noted in green in the diagram) is included in the merkle root by computing four additional pair-wise hashes HKL, HIJKL, HIJKLMNOP, and the merkle tree root (outlined in a dotted line in the diagram).

The code in Example 7-1 demonstrates the process of creating a merkle tree from the leaf-node hashes up to the root, using the libbitcoin library for some helper functions.

#include <bitcoin/bitcoin.hpp>bc::hash_digestcreate_merkle(bc::hash_list&merkle){// Stop if hash list is empty.if(merkle.empty())returnbc::null_hash;elseif(merkle.size()==1)returnmerkle[0];// While there is more than 1 hash in the list, keep looping...while(merkle.size()>1){// If number of hashes is odd, duplicate last hash in the list.if(merkle.size()%2!=0)merkle.push_back(merkle.back());// List size is now even.assert(merkle.size()%2==0);// New hash list.bc::hash_listnew_merkle;// Loop through hashes 2 at a time.for(autoit=merkle.begin();it!=merkle.end();it+=2){// Join both current hashes together (concatenate).bc::data_chunkconcat_data(bc::hash_size*2);autoconcat=bc::make_serializer(concat_data.begin());concat.write_hash(*it);concat.write_hash(*(it+1));assert(concat.iterator()==concat_data.end());// Hash both of the hashes.bc::hash_digestnew_root=bc::bitcoin_hash(concat_data);// Add this to the new list.new_merkle.push_back(new_root);}// This is the new list.merkle=new_merkle;// DEBUG output -------------------------------------std::cout<<"Current merkle hash list:"<<std::endl;for(constauto&hash:merkle)std::cout<<" "<<bc::encode_hex(hash)<<std::endl;std::cout<<std::endl;// --------------------------------------------------}// Finally we end up with a single item.returnmerkle[0];}intmain(){// Replace these hashes with ones from a block to reproduce the same merkle root.bc::hash_listtx_hashes{{bc::hash_literal("0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000"),bc::hash_literal("0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000011"),bc::hash_literal("0000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000022"),}};constbc::hash_digestmerkle_root=create_merkle(tx_hashes);std::cout<<"Result: "<<bc::encode_hex(merkle_root)<<std::endl;return0;}

Example 7-2 shows the result of compiling and running the merkle code.

$# Compile the merkle.cpp code$g++ -o merkle merkle.cpp$(pkg-config --cflags --libs libbitcoin)$# Run the merkle executable$./merkle Current merklehashlist: 32650049a0418e4380db0af81788635d8b65424d397170b8499cdc28c4d27006 30861db96905c8dc8b99398ca1cd5bd5b84ac3264a4e1b3e65afa1bcee7540c4 Current merklehashlist: d47780c084bad3830bcdaf6eace035e4c6cbf646d103795d22104fb105014ba3 Result: d47780c084bad3830bcdaf6eace035e4c6cbf646d103795d22104fb105014ba3

The efficiency of merkle trees becomes obvious as the scale increases. Table 7-3 shows the amount of data that needs to be exchanged as a merkle path to prove that a transaction is part of a block.

| Number of transactions | Approx. size of block | Path size (hashes) | Path size (bytes) |

16 transactions | 4 kilobytes | 4 hashes | 128 bytes |

512 transactions | 128 kilobytes | 9 hashes | 288 bytes |

2048 transactions | 512 kilobytes | 11 hashes | 352 bytes |

65,535 transactions | 16 megabytes | 16 hashes | 512 bytes |

As you can see from the table, while the block size increases rapidly, from 4 KB with 16 transactions to a block size of 16 MB to fit 65,535 transactions, the merkle path required to prove the inclusion of a transaction increases much more slowly, from 128 bytes to only 512 bytes. With merkle trees, a node can download just the block headers (80 bytes per block) and still be able to identify a transaction’s inclusion in a block by retrieving a small merkle path from a full node, without storing or transmitting the vast majority of the blockchain, which might be several gigabytes in size. Nodes that do not maintain a full blockchain, called simplified payment verification (SPV nodes), use merkle paths to verify transactions without downloading full blocks.

Merkle Trees and Simplified Payment Verification (SPV)

Merkle trees are used extensively by SPV nodes. SPV nodes don’t have all transactions and do not download full blocks, just block headers. In order to verify that a transaction is included in a block, without having to download all the transactions in the block, they use an authentication path, or merkle path.

Consider, for example, an SPV node that is interested in incoming payments to an address contained in its wallet. The SPV node will establish a bloom filter on its connections to peers to limit the transactions received to only those containing addresses of interest. When a peer sees a transaction that matches the bloom filter, it will send that block using a merkleblock message. The merkleblock message contains the block header as well as a merkle path that links the transaction of interest to the merkle root in the block. The SPV node can use this merkle path to connect the transaction to the block and verify that the transaction is included in the block. The SPV node also uses the block header to link the block to the rest of the blockchain. The combination of these two links, between the transaction and block, and between the block and blockchain, proves that the transaction is recorded in the blockchain. All in all, the SPV node will have received less than a kilobyte of data for the block header and merkle path, an amount of data that is more than a thousand times less than a full block (about 1 megabyte currently).

Get Mastering Bitcoin now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.