Chapter 5. Transactions

Introduction

Transactions are the most important part of the bitcoin system. Everything else in bitcoin is designed to ensure that transactions can be created, propagated on the network, validated, and finally added to the global ledger of transactions (the blockchain). Transactions are data structures that encode the transfer of value between participants in the bitcoin system. Each transaction is a public entry in bitcoin’s blockchain, the global double-entry bookkeeping ledger.

In this chapter we will examine all the various forms of transactions, what they contain, how to create them, how they are verified, and how they become part of the permanent record of all transactions.

Transaction Lifecycle

A transaction’s lifecycle starts with the transaction’s creation, also known as origination. The transaction is then signed with one or more signatures indicating the authorization to spend the funds referenced by the transaction. The transaction is then broadcast on the bitcoin network, where each network node (participant) validates and propagates the transaction until it reaches (almost) every node in the network. Finally, the transaction is verified by a mining node and included in a block of transactions that is recorded on the blockchain.

Once recorded on the blockchain and confirmed by sufficient subsequent blocks (confirmations), the transaction is a permanent part of the bitcoin ledger and is accepted as valid by all participants. The funds allocated to a new owner by the transaction can then be spent in a new transaction, extending the chain of ownership and beginning the lifecycle of a transaction again.

Creating Transactions

In some ways it helps to think of a transaction in the same way as a paper check. Like a check, a transaction is an instrument that expresses the intent to transfer money and is not visible to the financial system until it is submitted for execution. Like a check, the originator of the transaction does not have to be the one signing the transaction.

Transactions can be created online or offline by anyone, even if the person creating the transaction is not an authorized signer on the account. For example, an accounts payable clerk might process payable checks for signature by the CEO. Similarly, an accounts payable clerk can create bitcoin transactions and then have the CEO apply digital signatures to make them valid. Whereas a check references a specific account as the source of the funds, a bitcoin transaction references a specific previous transaction as its source, rather than an account.

Once a transaction has been created, it is signed by the owner (or owners) of the source funds. If it is properly formed and signed, the signed transaction is now valid and contains all the information needed to execute the transfer of funds. Finally, the valid transaction has to reach the bitcoin network so that it can be propagated until it reaches a miner for inclusion in the pubic ledger (the blockchain).

Broadcasting Transactions to the Bitcoin Network

First, a transaction needs to be delivered to the bitcoin network so that it can be propagated and included in the blockchain. In essence, a bitcoin transaction is just 300 to 400 bytes of data and has to reach any one of tens of thousands of bitcoin nodes. The senders do not need to trust the nodes they use to broadcast the transaction, as long as they use more than one to ensure that it propagates. The nodes don’t need to trust the sender or establish the sender’s “identity.” Because the transaction is signed and contains no confidential information, private keys, or credentials, it can be publicly broadcast using any underlying network transport that is convenient. Unlike credit card transactions, for example, which contain sensitive information and can only be transmitted on encrypted networks, a bitcoin transaction can be sent over any network. As long as the transaction can reach a bitcoin node that will propagate it into the bitcoin network, it doesn’t matter how it is transported to the first node.

Bitcoin transactions can therefore be transmitted to the bitcoin network over insecure networks such as WiFi, Bluetooth, NFC, Chirp, barcodes, or by copying and pasting into a web form. In extreme cases, a bitcoin transaction could be transmitted over packet radio, satellite relay, or shortwave using burst transmission, spread spectrum, or frequency hopping to evade detection and jamming. A bitcoin transaction could even be encoded as smileys (emoticons) and posted in a public forum or sent as a text message or Skype chat message. Bitcoin has turned money into a data structure, making it virtually impossible to stop anyone from creating and executing a bitcoin transaction.

Propagating Transactions on the Bitcoin Network

Once a bitcoin transaction is sent to any node connected to the bitcoin network, the transaction will be validated by that node. If valid, that node will propagate it to the other nodes to which it is connected, and a success message will be returned synchronously to the originator. If the transaction is invalid, the node will reject it and synchronously return a rejection message to the originator.

The bitcoin network is a peer-to-peer network, meaning that each bitcoin node is connected to a few other bitcoin nodes that it discovers during startup through the peer-to-peer protocol. The entire network forms a loosely connected mesh without a fixed topology or any structure, making all nodes equal peers. Messages, including transactions and blocks, are propagated from each node to all the peers to which it is connected, a process called “flooding.” A new validated transaction injected into any node on the network will be sent to all of the nodes connected to it (neighbors), each of which will send the transaction to all its neighbors, and so on. In this way, within a few seconds a valid transaction will propagate in an exponentially expanding ripple across the network until all nodes in the network have received it.

The bitcoin network is designed to propagate transactions and blocks to all nodes in an efficient and resilient manner that is resistant to attacks. To prevent spamming, denial-of-service attacks, or other nuisance attacks against the bitcoin system, every node independently validates every transaction before propagating it further. A malformed transaction will not get beyond one node. The rules by which transactions are validated are explained in more detail in Independent Verification of Transactions.

Transaction Structure

A transaction is a data structure that encodes a transfer of value from a source of funds, called an input, to a destination, called an output. Transaction inputs and outputs are not related to accounts or identities. Instead, you should think of them as bitcoin amounts—chunks of bitcoin—being locked with a specific secret that only the owner, or person who knows the secret, can unlock. A transaction contains a number of fields, as shown in Table 5-1.

| Size | Field | Description |

4 bytes | Version | Specifies which rules this transaction follows |

1–9 bytes (VarInt) | Input Counter | How many inputs are included |

Variable | Inputs | One or more transaction inputs |

1–9 bytes (VarInt) | Output Counter | How many outputs are included |

Variable | Outputs | One or more transaction outputs |

4 bytes | Locktime | A Unix timestamp or block number |

Transaction Outputs and Inputs

The fundamental building block of a bitcoin transaction is an unspent transaction output, or UTXO. UTXO are indivisible chunks of bitcoin currency locked to a specific owner, recorded on the blockchain, and recognized as currency units by the entire network. The bitcoin network tracks all available (unspent) UTXO currently numbering in the millions. Whenever a user receives bitcoin, that amount is recorded within the blockchain as a UTXO. Thus, a user’s bitcoin might be scattered as UTXO amongst hundreds of transactions and hundreds of blocks. In effect, there is no such thing as a stored balance of a bitcoin address or account; there are only scattered UTXO, locked to specific owners. The concept of a user’s bitcoin balance is a derived construct created by the wallet application. The wallet calculates the user’s balance by scanning the blockchain and aggregating all UTXO belonging to that user.

Tip

There are no accounts or balances in bitcoin; there are only unspent transaction outputs (UTXO) scattered in the blockchain.

A UTXO can have an arbitrary value denominated as a multiple of satoshis. Just like dollars can be divided down to two decimal places as cents, bitcoins can be divided down to eight decimal places as satoshis. Although UTXO can be any arbitrary value, once created it is indivisible just like a coin that cannot be cut in half. If a UTXO is larger than the desired value of a transaction, it must still be consumed in its entirety and change must be generated in the transaction. In other words, if you have a 20 bitcoin UTXO and want to pay 1 bitcoin, your transaction must consume the entire 20 bitcoin UTXO and produce two outputs: one paying 1 bitcoin to your desired recipient and another paying 19 bitcoin in change back to your wallet. As a result, most bitcoin transactions will generate change.

Imagine a shopper buying a $1.50 beverage, reaching into her wallet and trying to find a combination of coins and bank notes to cover the $1.50 cost. The shopper will choose exact change if available (a dollar bill and two quarters), or a combination of smaller denominations (six quarters), or if necessary, a larger unit such as a five dollar bank note. If she hands too much money, say $5, to the shop owner, she will expect $3.50 change, which she will return to her wallet and have available for future transactions.

Similarly, a bitcoin transaction must be created from a user’s UTXO in whatever denominations that user has available. Users cannot cut a UTXO in half any more than they can cut a dollar bill in half and use it as currency. The user’s wallet application will typically select from the user’s available UTXO various units to compose an amount greater than or equal to the desired transaction amount.

As with real life, the bitcoin application can use several strategies to satisfy the purchase amount: combining several smaller units, finding exact change, or using a single unit larger than the transaction value and making change. All of this complex assembly of spendable UTXO is done by the user’s wallet automatically and is invisible to users. It is only relevant if you are programmatically constructing raw transactions from UTXO.

The UTXO consumed by a transaction are called transaction inputs, and the UTXO created by a transaction are called transaction outputs. This way, chunks of bitcoin value move forward from owner to owner in a chain of transactions consuming and creating UTXO. Transactions consume UTXO by unlocking it with the signature of the current owner and create UTXO by locking it to the bitcoin address of the new owner.

The exception to the output and input chain is a special type of transaction called the coinbase transaction, which is the first transaction in each block. This transaction is placed there by the “winning” miner and creates brand-new bitcoin payable to that miner as a reward for mining. This is how bitcoin’s money supply is created during the mining process, as we will see in Chapter 8.

Tip

What comes first? Inputs or outputs, the chicken or the egg? Strictly speaking, outputs come first because coinbase transactions, which generate new bitcoin, have no inputs and create outputs from nothing.

Transaction Outputs

Every bitcoin transaction creates outputs, which are recorded on the bitcoin ledger. Almost all of these outputs, with one exception (see Data Output (OP_RETURN)) create spendable chunks of bitcoin called unspent transaction outputs or UTXO, which are then recognized by the whole network and available for the owner to spend in a future transaction. Sending someone bitcoin is creating an unspent transaction output (UTXO) registered to their address and available for them to spend.

UTXO are tracked by every full-node bitcoin client as a data set called the UTXO set or UTXO pool, held in a database. New transactions consume (spend) one or more of these outputs from the UTXO set.

Transaction outputs consist of two parts:

The transaction scripting language, used in the locking script mentioned previously, is discussed in detail in Transaction Scripts and Script Language. Table 5-2 shows the structure of a transaction output.

| Size | Field | Description |

8 bytes | Amount | Bitcoin value in satoshis (10-8 bitcoin) |

1-9 bytes (VarInt) | Locking-Script Size | Locking-Script length in bytes, to follow |

Variable | Locking-Script | A script defining the conditions needed to spend the output |

In Example 5-1, we use the blockchain.info API to find the unspent outputs (UTXO) of a specific address.

# get unspent outputs from blockchain APIimportjsonimportrequests# example addressaddress='1Dorian4RoXcnBv9hnQ4Y2C1an6NJ4UrjX'# The API URL is https://blockchain.info/unspent?active=<address># It returns a JSON object with a list "unspent_outputs", containing UTXO, like this:#{ "unspent_outputs":[# {# "tx_hash":"ebadfaa92f1fd29e2fe296eda702c48bd11ffd52313e986e99ddad9084062167",# "tx_index":51919767,# "tx_output_n": 1,# "script":"76a9148c7e252f8d64b0b6e313985915110fcfefcf4a2d88ac",# "value": 8000000,# "value_hex": "7a1200",# "confirmations":28691# },# ...#]}resp=requests.get('https://blockchain.info/unspent?active=%s'%address)utxo_set=json.loads(resp.text)["unspent_outputs"]forutxoinutxo_set:"%s:%d-%ldSatoshis"%(utxo['tx_hash'],utxo['tx_output_n'],utxo['value'])

Running the script, we see a list of transaction IDs, a colon, the index number of the specific unspent transaction output (UTXO), and the value of that UTXO in satoshis. The locking script is not shown in the output in Example 5-2.

$python get-utxo.py ebadfaa92f1fd29e2fe296eda702c48bd11ffd52313e986e99ddad9084062167:1 -8000000Satoshis 6596fd070679de96e405d52b51b8e1d644029108ec4cbfe451454486796a1ecf:0 -16050000Satoshis 74d788804e2aae10891d72753d1520da1206e6f4f20481cc1555b7f2cb44aca0:0 -5000000Satoshis b2affea89ff82557c60d635a2a3137b8f88f12ecec85082f7d0a1f82ee203ac4:0 -10000000Satoshis ...

Spending conditions (encumbrances)

Transaction outputs associate a specific amount (in satoshis) to a specific encumbrance or locking script that defines the condition that must be met to spend that amount. In most cases, the locking script will lock the output to a specific bitcoin address, thereby transferring ownership of that amount to the new owner. When Alice paid Bob’s Cafe for a cup of coffee, her transaction created a 0.015 bitcoin output encumbered or locked to the cafe’s bitcoin address. That 0.015 bitcoin output was recorded on the blockchain and became part of the Unspent Transaction Output set, meaning it showed in Bob’s wallet as part of the available balance. When Bob chooses to spend that amount, his transaction will release the encumbrance, unlocking the output by providing an unlocking script containing a signature from Bob’s private key.

Transaction Inputs

In simple terms, transaction inputs are pointers to UTXO. They point to a specific UTXO by reference to the transaction hash and sequence number where the UTXO is recorded in the blockchain. To spend UTXO, a transaction input also includes unlocking scripts that satisfy the spending conditions set by the UTXO. The unlocking script is usually a signature proving ownership of the bitcoin address that is in the locking script.

When users make a payment, their wallet constructs a transaction by selecting from the available UTXO. For example, to make a 0.015 bitcoin payment, the wallet app may select a 0.01 UTXO and a 0.005 UTXO, using them both to add up to the desired payment amount.

In Example 5-3, we show the use of a “greedy” algorithm to select from available UTXO in order to make a specific payment amount. In the example, the available UTXO are provided as a constant array, but in reality, the available UTXO would be retrieved with an RPC call to Bitcoin Core, or to a third-party API as shown in Example 5-1.

# Selects outputs from a UTXO list using a greedy algorithm.fromsysimportargvclassOutputInfo:def__init__(self,tx_hash,tx_index,value):self.tx_hash=tx_hashself.tx_index=tx_indexself.value=valuedef__repr__(self):return"<%s:%swith%sSatoshis>"%(self.tx_hash,self.tx_index,self.value)# Select optimal outputs for a send from unspent outputs list.# Returns output list and remaining change to be sent to# a change address.defselect_outputs_greedy(unspent,min_value):# Fail if empty.ifnotunspent:returnNone# Partition into 2 lists.lessers=[utxoforutxoinunspentifutxo.value<min_value]greaters=[utxoforutxoinunspentifutxo.value>=min_value]key_func=lambdautxo:utxo.valueifgreaters:# Not-empty. Find the smallest greater.min_greater=min(greaters)change=min_greater.value-min_valuereturn[min_greater],change# Not found in greaters. Try several lessers instead.# Rearrange them from biggest to smallest. We want to use the least# amount of inputs as possible.lessers.sort(key=key_func,reverse=True)result=[]accum=0forutxoinlessers:result.append(utxo)accum+=utxo.valueifaccum>=min_value:change=accum-min_valuereturnresult,"Change:%dSatoshis"%change# No results found.returnNone,0defmain():unspent=[OutputInfo("ebadfaa92f1fd29e2fe296eda702c48bd11ffd52313e986e99ddad9084062167",1,8000000),OutputInfo("6596fd070679de96e405d52b51b8e1d644029108ec4cbfe451454486796a1ecf",0,16050000),OutputInfo("b2affea89ff82557c60d635a2a3137b8f88f12ecec85082f7d0a1f82ee203ac4",0,10000000),OutputInfo("7dbc497969c7475e45d952c4a872e213fb15d45e5cd3473c386a71a1b0c136a1",0,25000000),OutputInfo("55ea01bd7e9afd3d3ab9790199e777d62a0709cf0725e80a7350fdb22d7b8ec6",17,5470541),OutputInfo("12b6a7934c1df821945ee9ee3b3326d07ca7a65fd6416ea44ce8c3db0c078c64",0,10000000),OutputInfo("7f42eda67921ee92eae5f79bd37c68c9cb859b899ce70dba68c48338857b7818",0,16100000),]iflen(argv)>1:target=long(argv[1])else:target=55000000"For transaction amount%dSatoshis (%fbitcoin) use: "%(target,target/10.0**8)select_outputs_greedy(unspent,target)if__name__=="__main__":main()

If we run the select-utxo.py script without a parameter, it will attempt to construct a set of UTXO (and change) for a payment of 55,000,000 satoshis (0.55 bitcoin). If you provide a target payment amount as a parameter, the script will select UTXO to make that target payment amount. In Example 5-4, we run the script trying to make a payment of 0.5 bitcoin or 50,000,000 satoshis.

$ python select-utxo.py 50000000 For transaction amount 50000000 Satoshis (0.500000 bitcoin) use: ([<7dbc497969c7475e45d952c4a872e213fb15d45e5cd3473c386a71a1b0c136a1:0 with 25000000 Satoshis>, <7f42eda67921ee92eae5f79bd37c68c9cb859b899ce70dba68c48338857b7818:0 with 16100000 Satoshis>, <6596fd070679de96e405d52b51b8e1d644029108ec4cbfe451454486796a1ecf:0 with 16050000 Satoshis>], 'Change: 7150000 Satoshis')

Once the UTXO is selected, the wallet then produces unlocking scripts containing signatures for each of the UTXO, thereby making them spendable by satisfying their locking script conditions. The wallet adds these UTXO references and unlocking scripts as inputs to the transaction. Table 5-3 shows the structure of a transaction input.

| Size | Field | Description |

32 bytes | Transaction Hash | Pointer to the transaction containing the UTXO to be spent |

4 bytes | Output Index | The index number of the UTXO to be spent; first one is 0 |

1-9 bytes (VarInt) | Unlocking-Script Size | Unlocking-Script length in bytes, to follow |

Variable | Unlocking-Script | A script that fulfills the conditions of the UTXO locking script. |

4 bytes | Sequence Number | Currently disabled Tx-replacement feature, set to 0xFFFFFFFF |

Note

The sequence number is used to override a transaction prior to the expiration of the transaction locktime, which is a feature that is currently disabled in bitcoin. Most transactions set this value to the maximum integer value (0xFFFFFFFF) and it is ignored by the bitcoin network. If the transaction has a nonzero locktime, at least one of its inputs must have a sequence number below 0xFFFFFFFF in order to enable locktime.

Transaction Fees

Most transactions include transaction fees, which compensate the bitcoin miners for securing the network. Mining and the fees and rewards collected by miners are discussed in more detail in Chapter 8. This section examines how transaction fees are included in a typical transaction. Most wallets calculate and include transaction fees automatically. However, if you are constructing transactions programmatically, or using a command-line interface, you must manually account for and include these fees.

Transaction fees serve as an incentive to include (mine) a transaction into the next block and also as a disincentive against “spam” transactions or any kind of abuse of the system, by imposing a small cost on every transaction. Transaction fees are collected by the miner who mines the block that records the transaction on the blockchain.

Transaction fees are calculated based on the size of the transaction in kilobytes, not the value of the transaction in bitcoin. Overall, transaction fees are set based on market forces within the bitcoin network. Miners prioritize transactions based on many different criteria, including fees, and might even process transactions for free under certain circumstances. Transaction fees affect the processing priority, meaning that a transaction with sufficient fees is likely to be included in the next-most–mined block, whereas a transaction with insufficient or no fees might be delayed, processed on a best-effort basis after a few blocks, or not processed at all. Transaction fees are not mandatory, and transactions without fees might be processed eventually; however, including transaction fees encourages priority processing.

Over time, the way transaction fees are calculated and the effect they have on transaction prioritization has been evolving. At first, transaction fees were fixed and constant across the network. Gradually, the fee structure has been relaxed so that it may be influenced by market forces, based on network capacity and transaction volume. The current minimum transaction fee is fixed at 0.0001 bitcoin or a tenth of a milli-bitcoin per kilobyte, recently decreased from one milli-bitcoin. Most transactions are less than one kilobyte; however, those with multiple inputs or outputs can be larger. In future revisions of the bitcoin protocol, it is expected that wallet applications will use statistical analysis to calculate the most appropriate fee to attach to a transaction based on the average fees of recent transactions.

The current algorithm used by miners to prioritize transactions for inclusion in a block based on their fees is examined in detail in Chapter 8.

Adding Fees to Transactions

The data structure of transactions does not have a field for fees. Instead, fees are implied as the difference between the sum of inputs and the sum of outputs. Any excess amount that remains after all outputs have been deducted from all inputs is the fee that is collected by the miners.

Transaction fees are implied, as the excess of inputs minus outputs:

Fees = Sum(Inputs) – Sum(Outputs)

This is a somewhat confusing element of transactions and an important point to understand, because if you are constructing your own transactions you must ensure you do not inadvertently include a very large fee by underspending the inputs. That means that you must account for all inputs, if necessary by creating change, or you will end up giving the miners a very big tip!

For example, if you consume a 20-bitcoin UTXO to make a 1-bitcoin payment, you must include a 19-bitcoin change output back to your wallet. Otherwise, the 19-bitcoin “leftover” will be counted as a transaction fee and will be collected by the miner who mines your transaction in a block. Although you will receive priority processing and make a miner very happy, this is probably not what you intended.

Warning

If you forget to add a change output in a manually constructed transaction, you will be paying the change as a transaction fee. “Keep the change!” might not be what you intended.

Let’s see how this works in practice, by looking at Alice’s coffee purchase again. Alice wants to spend 0.015 bitcoin to pay for coffee. To ensure this transaction is processed promptly, she will want to include a transaction fee, say 0.001. That will mean that the total cost of the transaction will be 0.016. Her wallet must therefore source a set of UTXO that adds up to 0.016 bitcoin or more and, if necessary, create change. Let’s say her wallet has a 0.2-bitcoin UTXO available. It will therefore need to consume this UTXO, create one output to Bob’s Cafe for 0.015, and a second output with 0.184 bitcoin in change back to her own wallet, leaving 0.001 bitcoin unallocated, as an implicit fee for the transaction.

Now let’s look at a different scenario. Eugenia, our children’s charity director in the Philippines, has completed a fundraiser to purchase school books for the children. She received several thousand small donations from people all around the world, totaling 50 bitcoin, so her wallet is full of very small payments (UTXO). Now she wants to purchase hundreds of school books from a local publisher, paying in bitcoin.

As Eugenia’s wallet application tries to construct a single larger payment transaction, it must source from the available UTXO set, which is composed of many smaller amounts. That means that the resulting transaction will source from more than a hundred small-value UTXO as inputs and only one output, paying the book publisher. A transaction with that many inputs will be larger than one kilobyte, perhaps 2 to 3 kilobytes in size. As a result, it will require a higher fee than the minimal network fee of 0.0001 bitcoin.

Eugenia’s wallet application will calculate the appropriate fee by measuring the size of the transaction and multiplying that by the per-kilobyte fee. Many wallets will overpay fees for larger transactions to ensure the transaction is processed promptly. The higher fee is not because Eugenia is spending more money, but because her transaction is more complex and larger in size—the fee is independent of the transaction’s bitcoin value.

Transaction Chaining and Orphan Transactions

As we have seen, transactions form a chain, whereby one transaction spends the outputs of the previous transaction (known as the parent) and creates outputs for a subsequent transaction (known as the child). Sometimes an entire chain of transactions depending on each other—say a parent, child, and grandchild transaction—are created at the same time, to fulfill a complex transactional workflow that requires valid children to be signed before the parent is signed. For example, this is a technique used in CoinJoin transactions where multiple parties join transactions together to protect their privacy.

When a chain of transactions is transmitted across the network, they don’t always arrive in the same order. Sometimes, the child might arrive before the parent. In that case, the nodes that see a child first can see that it references a parent transaction that is not yet known. Rather than reject the child, they put it in a temporary pool to await the arrival of its parent and propagate it to every other node. The pool of transactions without parents is known as the orphan transaction pool. Once the parent arrives, any orphans that reference the UTXO created by the parent are released from the pool, revalidated recursively, and then the entire chain of transactions can be included in the transaction pool, ready to be mined in a block. Transaction chains can be arbitrarily long, with any number of generations transmitted simultaneously. The mechanism of holding orphans in the orphan pool ensures that otherwise valid transactions will not be rejected just because their parent has been delayed and that eventually the chain they belong to is reconstructed in the correct order, regardless of the order of arrival.

There is a limit to the number of orphan transactions stored in memory, to prevent a denial-of-service attack against bitcoin nodes. The limit is defined as MAX_ORPHAN_TRANSACTIONS in the source code of the bitcoin reference client. If the number of orphan transactions in the pool exceeds MAX_ORPHAN_TRANSACTIONS, one or more randomly selected orphan transactions are evicted from the pool, until the pool size is back within limits.

Transaction Scripts and Script Language

Bitcoin clients validate transactions by executing a script, written in a Forth-like scripting language. Both the locking script (encumbrance) placed on a UTXO and the unlocking script that usually contains a signature are written in this scripting language. When a transaction is validated, the unlocking script in each input is executed alongside the corresponding locking script to see if it satisfies the spending condition.

Today, most transactions processed through the bitcoin network have the form “Alice pays Bob” and are based on the same script called a Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash script. However, the use of scripts to lock outputs and unlock inputs means that through use of the programming language, transactions can contain an infinite number of conditions. Bitcoin transactions are not limited to the “Alice pays Bob” form and pattern.

This is only the tip of the iceberg of possibilities that can be expressed with this scripting language. In this section, we will demonstrate the components of the bitcoin transaction scripting language and show how it can be used to express complex conditions for spending and how those conditions can be satisfied by unlocking scripts.

Tip

Bitcoin transaction validation is not based on a static pattern, but instead is achieved through the execution of a scripting language. This language allows for a nearly infinite variety of conditions to be expressed. This is how bitcoin gets the power of “programmable money.”

Script Construction (Lock + Unlock)

Bitcoin’s transaction validation engine relies on two types of scripts to validate transactions: a locking script and an unlocking script.

A locking script is an encumbrance placed on an output, and it specifies the conditions that must be met to spend the output in the future. Historically, the locking script was called a scriptPubKey, because it usually contained a public key or bitcoin address. In this book we refer to it as a “locking script” to acknowledge the much broader range of possibilities of this scripting technology. In most bitcoin applications, what we refer to as a locking script will appear in the source code as scriptPubKey.

An unlocking script is a script that “solves,” or satisfies, the conditions placed on an output by a locking script and allows the output to be spent. Unlocking scripts are part of every transaction input, and most of the time they contain a digital signature produced by the user’s wallet from his or her private key. Historically, the unlocking script is called scriptSig, because it usually contained a digital signature. In most bitcoin applications, the source code refers to the unlocking script as scriptSig. In this book, we refer to it as an “unlocking script” to acknowledge the much broader range of locking script requirements, because not all unlocking scripts must contain signatures.

Every bitcoin client will validate transactions by executing the locking and unlocking scripts together. For each input in the transaction, the validation software will first retrieve the UTXO referenced by the input. That UTXO contains a locking script defining the conditions required to spend it. The validation software will then take the unlocking script contained in the input that is attempting to spend this UTXO and execute the two scripts.

In the original bitcoin client, the unlocking and locking scripts were concatenated and executed in sequence. For security reasons, this was changed in 2010, because of a vulnerability that allowed a malformed unlocking script to push data onto the stack and corrupt the locking script. In the current implementation, the scripts are executed separately with the stack transferred between the two executions, as described next.

First, the unlocking script is executed, using the stack execution engine. If the unlocking script executed without errors (e.g., it has no “dangling” operators left over), the main stack (not the alternate stack) is copied and the locking script is executed. If the result of executing the locking script with the stack data copied from the unlocking script is “TRUE,” the unlocking script has succeeded in resolving the conditions imposed by the locking script and, therefore, the input is a valid authorization to spend the UTXO. If any result other than “TRUE” remains after execution of the combined script, the input is invalid because it has failed to satisfy the spending conditions placed on the UTXO. Note that the UTXO is permanently recorded in the blockchain, and therefore is invariable and is unaffected by failed attempts to spend it by reference in a new transaction. Only a valid transaction that correctly satisfies the conditions of the UTXO results in the UTXO being marked as “spent” and removed from the set of available (unspent) UTXO.

Figure 5-1 is an example of the unlocking and locking scripts for the most common type of bitcoin transaction (a payment to a public key hash), showing the combined script resulting from the concatenation of the unlocking and locking scripts prior to script validation.

Scripting Language

The bitcoin transaction script language, called Script, is a Forth-like reverse-polish notation stack-based execution language. If that sounds like gibberish, you probably haven’t studied 1960’s programming languages. Script is a very simple language that was designed to be limited in scope and executable on a range of hardware, perhaps as simple as an embedded device, such as a handheld calculator. It requires minimal processing and cannot do many of the fancy things modern programming languages can do. In the case of programmable money, that is a deliberate security feature.

Bitcoin’s scripting language is called a stack-based language because it uses a data structure called a stack. A stack is a very simple data structure, which can be visualized as a stack of cards. A stack allows two operations: push and pop. Push adds an item on top of the stack. Pop removes the top item from the stack.

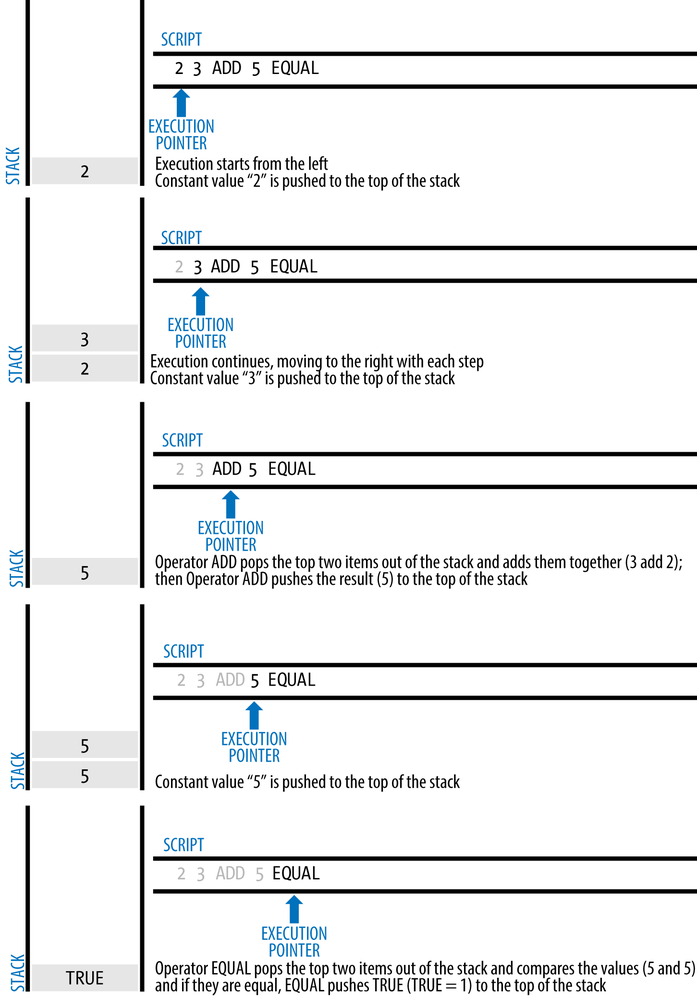

The scripting language executes the script by processing each item from left to right. Numbers (data constants) are pushed onto the stack. Operators push or pop one or more parameters from the stack, act on them, and might push a result onto the stack. For example, OP_ADD will pop two items from the stack, add them, and push the resulting sum onto the stack.

Conditional operators evaluate a condition, producing a boolean result of TRUE or FALSE. For example, OP_EQUAL pops two items from the stack and pushes TRUE (TRUE is represented by the number 1) if they are equal or FALSE (represented by zero) if they are not equal. Bitcoin transaction scripts usually contain a conditional operator, so that they can produce the TRUE result that signifies a valid transaction.

In Figure 5-2, the script 2 3 OP_ADD 5 OP_EQUAL demonstrates the arithmetic addition operator OP_ADD, adding two numbers and putting the result on the stack, followed by the conditional operator OP_EQUAL, which checks that the resulting sum is equal to 5. For brevity, the OP_ prefix is omitted in the step-by-step example.

The following is a slightly more complex script, which calculates 2 + 7 – 3 + 1. Notice that when the script contains several operators in a row, the stack allows the results of one operator to be acted upon by the next operator:

2 7 OP_ADD 3 OP_SUB 1 OP_ADD 7 OP_EQUAL

Try validating the preceding script yourself using pencil and paper. When the script execution ends, you should be left with the value TRUE on the stack.

Although most locking scripts refer to a bitcoin address or public key, thereby requiring proof of ownership to spend the funds, the script does not have to be that complex. Any combination of locking and unlocking scripts that results in a TRUE value is valid. The simple arithmetic we used as an example of the scripting language is also a valid locking script that can be used to lock a transaction output.

Use part of the arithmetic example script as the locking script:

3 OP_ADD 5 OP_EQUAL

which can be satisfied by a transaction containing an input with the unlocking script:

2

The validation software combines the locking and unlocking scripts and the resulting script is:

2 3 OP_ADD 5 OP_EQUAL

As we saw in the step-by-step example in Figure 5-2, when this script is executed, the result is OP_TRUE, making the transaction valid. Not only is this a valid transaction output locking script, but the resulting UTXO could be spent by anyone with the arithmetic skills to know that the number 2 satisfies the script.

Tip

Transactions are valid if the top result on the stack is TRUE (noted as {0x01}), any other non-zero value or if the stack is empty after script execution. Transactions are invalid if the top value on the stack is FALSE (a zero-length empty value, noted as {}) or if script execution is halted explicitly by an operator, such as OP_VERIFY, OP_RETURN, or a conditional terminator such as OP_ENDIF. See Appendix A for details.

Turing Incompleteness

The bitcoin transaction script language contains many operators, but is deliberately limited in one important way—there are no loops or complex flow control capabilities other than conditional flow control. This ensures that the language is not Turing Complete, meaning that scripts have limited complexity and predictable execution times. Script is not a general-purpose language. These limitations ensure that the language cannot be used to create an infinite loop or other form of “logic bomb” that could be embedded in a transaction in a way that causes a denial-of-service attack against the bitcoin network. Remember, every transaction is validated by every full node on the bitcoin network. A limited language prevents the transaction validation mechanism from being used as a vulnerability.

Stateless Verification

The bitcoin transaction script language is stateless, in that there is no state prior to execution of the script, or state saved after execution of the script. Therefore, all the information needed to execute a script is contained within the script. A script will predictably execute the same way on any system. If your system verifies a script, you can be sure that every other system in the bitcoin network will also verify the script, meaning that a valid transaction is valid for everyone and everyone knows this. This predictability of outcomes is an essential benefit of the bitcoin system.

Standard Transactions

In the first few years of bitcoin’s development, the developers introduced some limitations in the types of scripts that could be processed by the reference client. These limitations are encoded in a function called isStandard(), which defines five types of “standard” transactions. These limitations are temporary and might be lifted by the time you read this. Until then, the five standard types of transaction scripts are the only ones that will be accepted by the reference client and most miners who run the reference client. Although it is possible to create a nonstandard transaction containing a script that is not one of the standard types, you must find a miner who does not follow these limitations to mine that transaction into a block.

Check the source code of the Bitcoin Core client (the reference implementation) to see what is currently allowed as a valid transaction script.

The five standard types of transaction scripts are pay-to-public-key-hash (P2PKH), public-key, multi-signature (limited to 15 keys), pay-to-script-hash (P2SH), and data output (OP_RETURN), which are described in more detail in the following sections.

Pay-to-Public-Key-Hash (P2PKH)

The vast majority of transactions processed on the bitcoin network are P2PKH transactions. These contain a locking script that encumbers the output with a public key hash, more commonly known as a bitcoin address. Transactions that pay a bitcoin address contain P2PKH scripts. An output locked by a P2PKH script can be unlocked (spent) by presenting a public key and a digital signature created by the corresponding private key.

For example, let’s look at Alice’s payment to Bob’s Cafe again. Alice made a payment of 0.015 bitcoin to the cafe’s bitcoin address. That transaction output would have a locking script of the form:

OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <Cafe Public Key Hash> OP_EQUAL OP_CHECKSIG

The Cafe Public Key Hash is equivalent to the bitcoin address of the cafe, without the Base58Check encoding. Most applications would show the public key hash in hexadecimal encoding and not the familiar bitcoin address Base58Check format that begins with a “1”.

The preceding locking script can be satisfied with an unlocking script of the form:

<Cafe Signature> <Cafe Public Key>

The two scripts together would form the following combined validation script:

<Cafe Signature> <Cafe Public Key> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <Cafe Public Key Hash> OP_EQUAL OP_CHECKSIG

When executed, this combined script will evaluate to TRUE if, and only if, the unlocking script matches the conditions set by the locking script. In other words, the result will be TRUE if the unlocking script has a valid signature from the cafe’s private key that corresponds to the public key hash set as an encumbrance.

Figures 5-3 and 5-4 show (in two parts) a step-by-step execution of the combined script, which will prove this is a valid transaction.

Pay-to-Public-Key

Pay-to-public-key is a simpler form of a bitcoin payment than pay-to-public-key-hash. With this script form, the public key itself is stored in the locking script, rather than a public-key-hash as with P2PKH earlier, which is much shorter. Pay-to-public-key-hash was invented by Satoshi to make bitcoin addresses shorter, for ease of use. Pay-to-public-key is now most often seen in coinbase transactions, generated by older mining software that has not been updated to use P2PKH.

A pay-to-public-key locking script looks like this:

<Public Key A> OP_CHECKSIG

The corresponding unlocking script that must be presented to unlock this type of output is a simple signature, like this:

<Signature from Private Key A>

The combined script, which is validated by the transaction validation software, is:

<Signature from Private Key A> <Public Key A> OP_CHECKSIG

This script is a simple invocation of the CHECKSIG operator, which validates the signature as belonging to the correct key and returns TRUE on the stack.

Multi-Signature

Multi-signature scripts set a condition where N public keys are recorded in the script and at least M of those must provide signatures to release the encumbrance. This is also known as an M-of-N scheme, where N is the total number of keys and M is the threshold of signatures required for validation. For example, a 2-of-3 multi-signature is one where three public keys are listed as potential signers and at least two of those must be used to create signatures for a valid transaction to spend the funds. At this time, standard multi-signature scripts are limited to at most 15 listed public keys, meaning you can do anything from a 1-of-1 to a 15-of-15 multi-signature or any combination within that range. The limitation to 15 listed keys might be lifted by the time this book is published, so check the isStandard() function to see what is currently accepted by the network.

The general form of a locking script setting an M-of-N multi-signature condition is:

M <Public Key 1> <Public Key 2> ... <Public Key N> N OP_CHECKMULTISIG

where N is the total number of listed public keys and M is the threshold of required signatures to spend the output.

A locking script setting a 2-of-3 multi-signature condition looks like this:

2 <Public Key A> <Public Key B> <Public Key C> 3 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

The preceding locking script can be satisfied with an unlocking script containing pairs of signatures and public keys:

OP_0 <Signature B> <Signature C>

or any combination of two signatures from the private keys corresponding to the three listed public keys.

Note

The prefix OP_0 is required because of a bug in the original implementation of CHECKMULTISIG where one item too many is popped off the stack. It is ignored by CHECKMULTISIG and is simply a placeholder.

The two scripts together would form the combined validation script:

OP_0 <Signature B> <Signature C> 2 <Public Key A> <Public Key B> <Public Key C> 3 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

When executed, this combined script will evaluate to TRUE if, and only if, the unlocking script matches the conditions set by the locking script. In this case, the condition is whether the unlocking script has a valid signature from the two private keys that correspond to two of the three public keys set as an encumbrance.

Data Output (OP_RETURN)

Bitcoin’s distributed and timestamped ledger, the blockchain, has potential uses far beyond payments. Many developers have tried to use the transaction scripting language to take advantage of the security and resilience of the system for applications such as digital notary services, stock certificates, and smart contracts. Early attempts to use bitcoin’s script language for these purposes involved creating transaction outputs that recorded data on the blockchain; for example, to record a digital fingerprint of a file in such a way that anyone could establish proof-of-existence of that file on a specific date by reference to that transaction.

The use of bitcoin’s blockchain to store data unrelated to bitcoin payments is a controversial subject. Many developers consider such use abusive and want to discourage it. Others view it as a demonstration of the powerful capabilities of blockchain technology and want to encourage such experimentation. Those who object to the inclusion of non-payment data argue that it causes “blockchain bloat,” burdening those running full bitcoin nodes with carrying the cost of disk storage for data that the blockchain was not intended to carry. Moreover, such transactions create UTXO that cannot be spent, using the destination bitcoin address as a free-form 20-byte field. Because the address is used for data, it doesn’t correspond to a private key and the resulting UTXO can never be spent; it’s a fake payment. These transactions that can never be spent are therefore never removed from the UTXO set and cause the size of the UTXO database to forever increase, or “bloat.”

In version 0.9 of the Bitcoin Core client, a compromise was reached with the introduction of the OP_RETURN operator. OP_RETURN allows developers to add 80 bytes of nonpayment data to a transaction output. However, unlike the use of “fake” UTXO, the OP_RETURN operator creates an explicitly provably unspendable output, which does not need to be stored in the UTXO set. OP_RETURN outputs are recorded on the blockchain, so they consume disk space and contribute to the increase in the blockchain’s size, but they are not stored in the UTXO set and therefore do not bloat the UTXO memory pool and burden full nodes with the cost of more expensive RAM.

OP_RETURN scripts look like this:

OP_RETURN <data>

The data portion is limited to 80 bytes and most often represents a hash, such as the output from the SHA256 algorithm (32 bytes). Many applications put a prefix in front of the data to help identify the application. For example, the Proof of Existence digital notarization service uses the 8-byte prefix “DOCPROOF,” which is ASCII encoded as 44f4350524f4f46 in hexadecimal.

Keep in mind that there is no “unlocking script” that corresponds to OP_RETURN that could possibly be used to “spend” an OP_RETURN output. The whole point of OP_RETURN is that you can’t spend the money locked in that output, and therefore it does not need to be held in the UTXO set as potentially spendable—OP_RETURN is provably un-spendable. OP_RETURN is usually an output with a zero bitcoin amount, because any bitcoin assigned to such an output is effectively lost forever. If an OP_RETURN is encountered by the script validation software, it results immediately in halting the execution of the validation script and marking the transaction as invalid. Thus, if you accidentally reference an OP_RETURN output as an input in a transaction, that transaction is invalid.

A standard transaction (one that conforms to the isStandard() checks) can have only one OP_RETURN output. However, a single OP_RETURN output can be combined in a transaction with outputs of any other type.

Two new command-line options have been added in Bitcoin Core as of version 0.10. The option datacarrier controls relay and mining of OP_RETURN transactions, with the default set to “1” to allow them. The option datacarriersize takes a numeric argument specifying the maximum size in bytes of the OP_RETURN data, 40 bytes by default.

Note

OP_RETURN was initially proposed with a limit of 80 bytes, but the limit was reduced to 40 bytes when the feature was released. In February 2015, in version 0.10 of Bitcoin Core, the limit was raised back to 80 bytes. Nodes may choose not to relay or mine OP_RETURN, or only relay and mine OP_RETURN containing less than 80 bytes of data.

Pay-to-Script-Hash (P2SH)

Pay-to-script-hash (P2SH) was introduced in 2012 as a powerful new type of transaction that greatly simplifies the use of complex transaction scripts. To explain the need for P2SH, let’s look at a practical example.

In Chapter 1 we introduced Mohammed, an electronics importer based in Dubai. Mohammed’s company uses bitcoin’s multi-signature feature extensively for its corporate accounts. Multi-signature scripts are one of the most common uses of bitcoin’s advanced scripting capabilities and are a very powerful feature. Mohammed’s company uses a multi-signature script for all customer payments, known in accounting terms as “accounts receivable,” or AR. With the multi-signature scheme, any payments made by customers are locked in such a way that they require at least two signatures to release, from Mohammed and one of his partners or from his attorney who has a backup key. A multi-signature scheme like that offers corporate governance controls and protects against theft, embezzlement, or loss.

The resulting script is quite long and looks like this:

2 <Mohammed's Public Key> <Partner1 Public Key> <Partner2 Public Key> <Partner3 Public Key> <Attorney Public Key> 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

Although multi-signature scripts are a powerful feature, they are cumbersome to use. Given the preceding script, Mohammed would have to communicate this script to every customer prior to payment. Each customer would have to use special bitcoin wallet software with the ability to create custom transaction scripts, and each customer would have to understand how to create a transaction using custom scripts. Furthermore, the resulting transaction would be about five times larger than a simple payment transaction, because this script contains very long public keys. The burden of that extra-large transaction would be borne by the customer in the form of fees. Finally, a large transaction script like this would be carried in the UTXO set in RAM in every full node, until it was spent. All of these issues make using complex output scripts difficult in practice.

Pay-to-script-hash (P2SH) was developed to resolve these practical difficulties and to make the use of complex scripts as easy as a payment to a bitcoin address. With P2SH payments, the complex locking script is replaced with its digital fingerprint, a cryptographic hash. When a transaction attempting to spend the UTXO is presented later, it must contain the script that matches the hash, in addition to the unlocking script. In simple terms, P2SH means “pay to a script matching this hash, a script that will be presented later when this output is spent.”

In P2SH transactions, the locking script that is replaced by a hash is referred to as the redeem script because it is presented to the system at redemption time rather than as a locking script. Table 5-4 shows the script without P2SH and Table 5-5 shows the same script encoded with P2SH.

Locking Script | 2 PubKey1 PubKey2 PubKey3 PubKey4 PubKey5 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG |

Unlocking Script | Sig1 Sig2 |

Redeem Script | 2 PubKey1 PubKey2 PubKey3 PubKey4 PubKey5 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG |

Locking Script | OP_HASH160 <20-byte hash of redeem script> OP_EQUAL |

Unlocking Script | Sig1 Sig2 redeem script |

As you can see from the tables, with P2SH the complex script that details the conditions for spending the output (redeem script) is not presented in the locking script. Instead, only a hash of it is in the locking script and the redeem script itself is presented later, as part of the unlocking script when the output is spent. This shifts the burden in fees and complexity from the sender to the recipient (spender) of the transaction.

Let’s look at Mohammed’s company, the complex multi-signature script, and the resulting P2SH scripts.

First, the multi-signature script that Mohammed’s company uses for all incoming payments from customers:

2 <Mohammed's Public Key> <Partner1 Public Key> <Partner2 Public Key> <Partner3 Public Key> <Attorney Public Key> 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

If the placeholders are replaced by actual public keys (shown here as 520-bit numbers starting with 04) you can see that this script becomes very long:

2 04C16B8698A9ABF84250A7C3EA7EEDEF9897D1C8C6ADF47F06CF73370D74DCCA01CDCA79DCC5C395D7EEC6984D83F1F50C900A24DD47F569FD4193AF5DE762C58704A2192968D8655D6A935BEAF2CA23E3FB87A3495E7AF308EDF08DAC3C1FCBFC2C75B4B0F4D0B1B70CD2423657738C0C2B1D5CE65C97D78D0E34224858008E8B49047E63248B75DB7379BE9CDA8CE5751D16485F431E46117B9D0C1837C9D5737812F393DA7D4420D7E1A9162F0279CFC10F1E8E8F3020DECDBC3C0DD389D99779650421D65CBD7149B255382ED7F78E946580657EE6FDA162A187543A9D85BAAA93A4AB3A8F044DADA618D087227440645ABE8A35DA8C5B73997AD343BE5C2AFD94A5043752580AFA1ECED3C68D446BCAB69AC0BA7DF50D56231BE0AABF1FDEEC78A6A45E394BA29A1EDF518C022DD618DA774D207D137AAB59E0B000EB7ED238F4D800 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

This entire script can instead be represented by a 20-byte cryptographic hash, by first applying the SHA256 hashing algorithm and then applying the RIPEMD160 algorithm on the result. The 20-byte hash of the preceding script is:

54c557e07dde5bb6cb791c7a540e0a4796f5e97e

A P2SH transaction locks the output to this hash instead of the longer script, using the locking script:

OP_HASH160 54c557e07dde5bb6cb791c7a540e0a4796f5e97e OP_EQUAL

which, as you can see, is much shorter. Instead of “pay to this 5-key multi-signature script,” the P2SH equivalent transaction is “pay to a script with this hash.” A customer making a payment to Mohammed’s company need only include this much shorter locking script in his payment. When Mohammed wants to spend this UTXO, they must present the original redeem script (the one whose hash locked the UTXO) and the signatures necessary to unlock it, like this:

<Sig1> <Sig2> <2 PK1 PK2 PK3 PK4 PK5 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG>

The two scripts are combined in two stages. First, the redeem script is checked against the locking script to make sure the hash matches:

<2 PK1 PK2 PK3 PK4 PK5 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG> OP_HASH160 <redeem scriptHash> OP_EQUAL

If the redeem script hash matches, the unlocking script is executed on its own, to unlock the redeem script:

<Sig1> <Sig2> 2 PK1 PK2 PK3 PK4 PK5 5 OP_CHECKMULTISIG

Pay-to-script-hash addresses

Another important part of the P2SH feature is the ability to encode a script hash as an address, as defined in BIP0013. P2SH addresses are Base58Check encodings of the 20-byte hash of a script, just like bitcoin addresses are Base58Check encodings of the 20-byte hash of a public key. P2SH addresses use the version prefix “5”, which results in Base58Check-encoded addresses that start with a “3”. For example, Mohammed’s complex script, hashed and Base58Check-encoded as a P2SH address becomes 39RF6JqABiHdYHkfChV6USGMe6Nsr66Gzw. Now, Mohammed can give this “address” to his customers and they can use almost any bitcoin wallet to make a simple payment, as if it were a bitcoin address. The 3 prefix gives them a hint that this is a special type of address, one corresponding to a script instead of a public key, but otherwise it works in exactly the same way as a payment to a bitcoin address.

P2SH addresses hide all of the complexity, so that the person making a payment does not see the script.

Benefits of pay-to-script-hash

The pay-to-script-hash feature offers the following benefits compared to the direct use of complex scripts in locking outputs:

- Complex scripts are replaced by shorter fingerprints in the transaction output, making the transaction smaller.

- Scripts can be coded as an address, so the sender and the sender’s wallet don’t need complex engineering to implement P2SH.

- P2SH shifts the burden of constructing the script to the recipient, not the sender.

- P2SH shifts the burden in data storage for the long script from the output (which is in the UTXO set) to the input (stored on the blockchain).

- P2SH shifts the burden in data storage for the long script from the present time (payment) to a future time (when it is spent).

- P2SH shifts the transaction fee cost of a long script from the sender to the recipient, who has to include the long redeem script to spend it.

Redeem script and isStandard validation

Prior to version 0.9.2 of the Bitcoin Core client, pay-to-script-hash was limited to the standard types of bitcoin transaction scripts, by the isStandard() function. That means that the redeem script presented in the spending transaction could only be one of the standard types: P2PK, P2PKH, or multi-sig nature, excluding OP_RETURN and P2SH itself.

As of version 0.9.2 of the Bitcoin Core client, P2SH transactions can contain any valid script, making the P2SH standard much more flexible and allowing for experimentation with many novel and complex types of transactions.

Note that you are not able to put a P2SH inside a P2SH redeem script, because the P2SH specification is not recursive. You are also still not able to use OP_RETURN in a redeem script because OP_RETURN cannot be redeemed by definition.

Note that because the redeem script is not presented to the network until you attempt to spend a P2SH output, if you lock an output with the hash of an invalid transaction it will be processed regardless. However, you will not be able to spend it because the spending transaction, which includes the redeem script, will not be accepted because it is an invalid script. This creates a risk, because you can lock bitcoin in a P2SH that cannot be spent later. The network will accept the P2SH encumbrance even if it corresponds to an invalid redeem script, because the script hash gives no indication of the script it represents.

Warning

P2SH locking scripts contain the hash of a redeem script, which gives no clues as to the content of the redeem script itself. The P2SH transaction will be considered valid and accepted even if the redeem script is invalid. You might accidentally lock bitcoin in such a way that it cannot later be spent.

Get Mastering Bitcoin now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.