One of the great pleasures of using Unix with Mac OS X surrounding it is that you get the benefit of a truly wonderful graphical application environment and the underlying power of the raw Unix interface. A match made in heaven!

This chapter explains the how and the why: how to customize your Terminal environment both from the graphical user interface using Terminal → Window Settings and from the Unix shell by using shell configuration files, and why you’d want to use Unix in the first place. Let’s start with the question of why, shall we?

It’s an obvious question, particularly if you’re a long-time Macintosh person who is familiar and happy with the capabilities and logic of the graphical world, with its Aqua interface built on top of the Quartz rendering system. Dipping into the primarily text-based Unix tools on your Mac OS X system can give you even greater power and control over both your computer and your computing environment. There are other reasons, including that it’s fun and there are thousands of open source and otherwise freely downloadable Unix-based applications, particularly for science and engineering. But, fundamentally, it’s all about power and control.

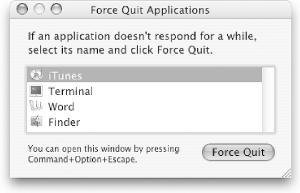

As an example, consider the difference between the graphical

Force Quit option

on the Apple menu and the Unix programs ps and

kill. While Force Quit is

more attractive, as shown in Figure 1-1, notice

that it lists only a very small number of applications.

By contrast, the

ps

(processor status) command used from within the

Terminal application (Applications → Utilities

→ Terminal) shows a complete and full list of every

application, utility, and system process running on the computer:

$ ps -ax

PID TT STAT TIME COMMAND

1 ?? Ss 0:00.04 /sbin/init

2 ?? Ss 0:00.19 /sbin/mach_init

78 ?? Ss 0:00.18 /usr/sbin/syslogd -s -m 0

84 ?? Ss 0:02.67 kextd

86 ?? Ss 0:01.51 /usr/sbin/configd

87 ?? Ss 0:01.12 /usr/sbin/diskarbitrationd

...

358 std Ss 0:00.03 login -pf taylor

359 std S 0:00.04 -bash

361 std R+ 0:00.01 ps axQuite a few applications, certainly many more than Force Quit suggests, are running. This is the key reason to learn and work with the Unix side of Mac OS X in addition to the attractive graphical facet of the operating system: to really know what’s going on and be able to make it match what you want and need.

Here’s another example. Suppose you just received a CD-ROM from a client with a few hundred files all in the main folder. You need to copy to your home directory just those files that have “-nt-” or “-dt-” as part of their filenames. Within the Finder, you’d be doomed to going through the list manually, a tedious and error-prone process. On the Unix command line, it’d be a breeze:

$cd /Volumes/MyCDROM$cp *-dt-* *-nt-* ~

Fast, easy, and doable by any and all Mac OS X users.

There are a million reasons why it’s helpful to know

Unix as a Mac OS X power user, and you’ll see them

demonstrated time and again throughout this book. They are shown in

even more detail in advanced books like

Mac OS X

Panther for Unix Geek

s, by Brian

Jepson and Ernest E.

Rothman (O’Reilly).

Get Learning Unix for Mac OS X Panther now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.