Chapter 1. Introducing vi and Vim

One of the most important day-to-day uses of a computer is working with text: composing new text, editing and rearranging existing text, deleting or rewriting incorrect and obsolete text. If you work with a word processing program such as Microsoft Word, that’s what you’re doing! If you are a programmer, you’re also working with text: the source code files of your program, and auxiliary files needed for development. Text editors process the contents of any text files, whether those files contain data, source code, or sentences.

This book is about text editing with two related text editors:

vi and Vim. vi has a long tradition as the standard Unix1

text editor. Vim builds on vi’s command mode and command language,

providing at least an order of magnitude more power and capability

than the original.

Text Editors and Text Editing

Let’s get started.

Text Editors

Unix text editors have evolved over time. Initially, there were line

editors, such as ed and ex, for use on serial terminals

that printed on continuous feed paper. (Yes, people really programmed

on such things! Including at least one of your authors.)

Line editors were called such because you worked

on your program one or a few lines at a time.

With the introduction of cathode-ray tube (CRT)

terminals with cursor addressing, line editors evolved into

screen editors, such as vi and Emacs. Screen editors let

you work with your files a full screen at a time and let you easily move

around the lines on the screen as you wished.

With the introduction of graphical user interface (GUI) environments,

screen editors evolved further into graphical text editors, where you

use a mouse to scroll the visible portion of your file, move to a particular

point in a file, and select text upon which to perform an operation.

Examples of such

text editors based on the X Window System are gedit on Gnome-based

systems and Notepad++ on MS-Windows. There are others.

Of particular interest to us is that the popular screen editors have

evolved into

graphical editors:2

GNU Emacs provides multiple X windows, as does Vim through its gvim version.

The graphical editors continue to work identically to their original

screen-based versions, making the transition to the GUI version

almost trivial.

Of all the standard editors on a Unix system, vi is

the most useful one for you to master.3

Unlike Emacs, it is available in nearly identical form on every modern

Unix system, thus providing a kind of text-editing lingua

franca.4

The same might be said of ed and ex, but screen

editors, and their GUI-based descendants, are much easier to use.

(So much so, in fact, that

line editors have generally fallen into disuse.)

vi exists in multiple incarnations. There is the original

Unix version, and there are multiple “clones”: programs written

from scratch to behave as vi does, but not based on the

original vi source code. Of these, Vim

has become the most popular.

In the chapters in Part I, we teach you how to use vi

in the general sense. Everything in these chapters applies to

all versions of vi. However, we do this in the context of

Vim, since that is the version you are likely to have on your

system. While reading, feel free to think of “vi”

as standing for “vi and Vim.”

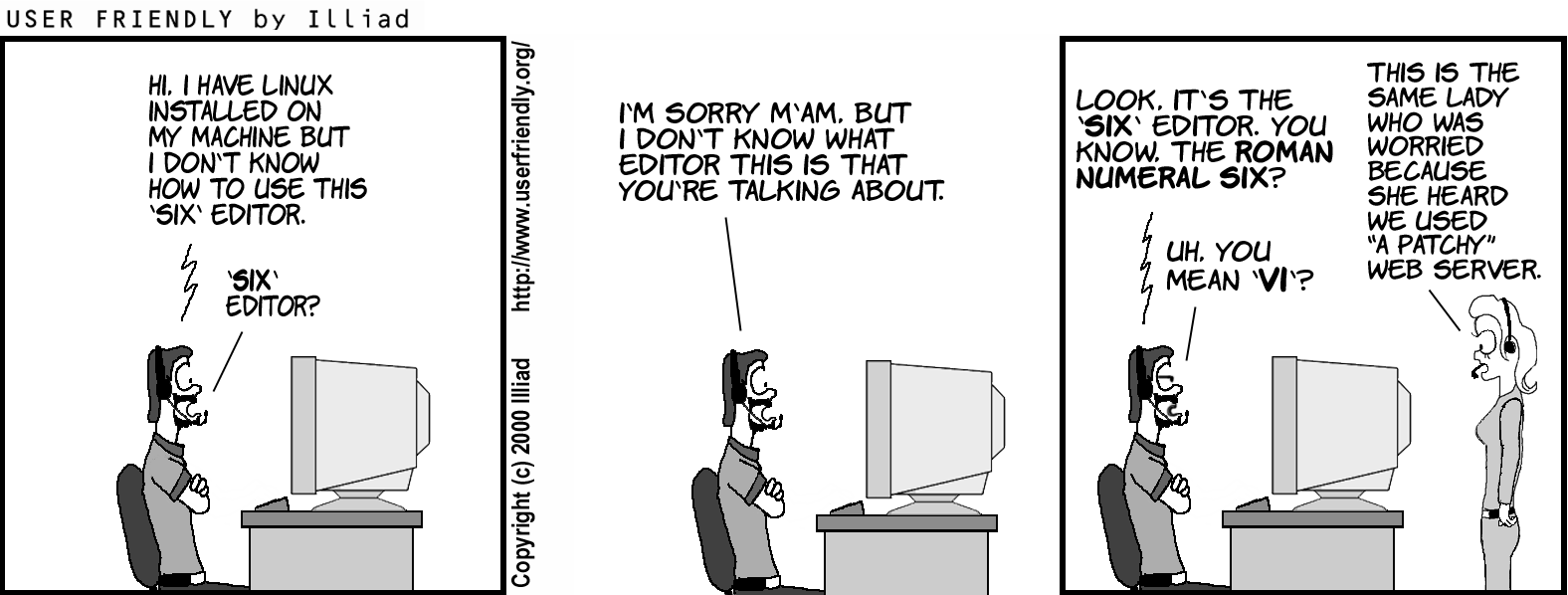

Note

vi is short for visual editor and is pronounced

“vee-eye.” This is illustrated graphically in

Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1. Correct pronunciation of vi

To many beginners, vi looks unintuitive and cumbersome—instead

of using special control keys for word processing functions and just

letting you type normally, it uses almost all of the regular keyboard keys for

issuing commands. When the keyboard keys are issuing commands, the editor

is said to be in command mode. You must be in a special insert

mode before you can type actual text on the screen. In addition,

there seem to be so many commands.

Once you start learning, however, you realize that the editor is well

designed. You need only a few keystrokes to tell it to do complex

tasks. As you learn vi, you learn shortcuts that transfer more and

more of the editing work to the computer—where it belongs.

vi and Vim (like any text editors) are not “what you see is what

you get” word processors. If you want to produce formatted

documents, you must type in specific instructions (sometimes called

formatting codes) that are used by a separate formatting

program to control the appearance of the printed copy. If you

want to indent several paragraphs, for instance, you put a code

where the indent begins and ends. Formatting codes allow you to

experiment with or change the appearance of your printed files, and

in many ways they give you much more control over the appearance of

your documents than a word processor does.

Formatting codes are the specific verbs in what are more generally known as markup languages.5 In recent years, markup languages have seen a resurgence in popularity. Of note are Markdown and AsciiDoc,6 although there are others as well. Perhaps the most widely used markup language today is the Hypertext Markup Language (HTML), used in the creation of internet web pages.

Besides the markup languages just mentioned,

Unix supports the troff

formatting package.7 The

TeX and LaTeX

formatters are popular, commonly available alternatives. The easiest

way to use any of these markup languages is with a text editor.

Note

vi does support some simple formatting mechanisms. For example,

you can tell it to automatically wrap when you come to the end of a line,

or to automatically indent new lines. In addition, Vim provides

automatic spellchecking.

As with any skill, the more editing you do, the easier the basics become, and the more you can accomplish. Once you are used to all the powers you have while editing, you may never want to return to any “simpler” editor.

Text Editing

What are the components of editing? First, you want to insert text (a forgotten word or a new or missing sentence), and you want to delete text (a stray character or an entire paragraph). You also need to change letters and words (to correct misspellings or to reflect a change of mind about a term). You might want to move text from one place to another part of your file. And, on occasion, you want to copy text to duplicate it in another part of your file.

Unlike many word processors, vi’s command mode is the initial or

default mode. Complex, interactive edits can be performed

with only a few keystrokes. To insert raw text, you simply give

any of the several “insert” commands and then type away.

One or two characters are used for the basic commands. For example:

i-

Insert

cw-

Change word

Using letters as commands, you can edit a file with great speed. You don’t have to memorize banks of function keys or stretch your fingers to reach awkward combinations of keys. You never have to remove your hands from the keyboard, or mess around with multiple levels of menus! Most of the commands can be remembered by the letters that perform them. Nearly all commands follow similar patterns and are related to each other.

In general, vi and Vim commands:

-

Are case sensitive (uppercase and lowercase keystrokes mean different things;

Iis different fromi). -

Are not shown (or “echoed”) on the screen when you type them.

-

Do not require that you press ENTER after a command.

There is also a group of commands that echo on the bottom line of the

screen. Bottom-line commands are preceded by different symbols. The

slash (/) and the question mark (?) begin search commands

and are discussed in

Chapter 3, “Moving Around in a Hurry”.

A colon (:) begins all ex

commands. ex commands are those used by the ex line editor. The

ex editor is available to you when you use any version of vi, because ex is

the underlying editor and vi is really just its “visual”

mode. ex commands and concepts are discussed fully in

Chapter 5, “Introducing the ex Editor”,

but this chapter introduces you to the ex commands to quit a file

without saving edits.

A Brief Historical Perspective

Before we dive into all the ins and outs of vi and Vim, it will help to

understand vi’s worldview of your environment. In particular,

this will help you make sense of many of vi’s otherwise more

obscure error messages and also appreciate how Vim has

evolved beyond the original vi.

vi dates back to a time when computer users worked on CRT terminals

connected via serial lines to central minicomputers. Hundreds of

different kinds of terminals existed and were in use worldwide. Each

one did the same kind of actions (clear the screen, move the cursor,

etc.), but the commands needed to make them do these actions were

different. In addition, the Unix system let you choose the characters

to use for backspace, generating an interrupt signal, and other commands

useful on serial terminals, such as suspending and resuming output. These

facilities were (and still are) managed with the stty command.

The original Berkeley Unix version of vi abstracted out the terminal control

information from the code (which was hard to change) into a text-file

database of terminal capabilities (which was easy to change),

managed by the termcap library. In the early 1980s, System V

introduced a binary terminal information database and terminfo

library. The two libraries were largely functionally equivalent. In

order to tell vi which terminal you had, you had to set the TERM

environment variable. This was typically done in a shell startup file

such as your personal .profile or .login.

The termcap library is no longer used. GNU/Linux and BSD

systems use the ncurses library, which provides a compatible

superset of the System V terminfo library’s database and

capabilities.

Today, everyone uses terminal emulators in a graphical environment

(such as Gnome Terminal). The system almost always takes care of setting

TERM for you.

Note

You can use Vim from a PC non-GUI console too, of course. This is very useful when doing system recovery work in single-user mode. There aren’t too many people left who would want to work this way on a regular basis, though.

For day-to-day use,

it is likely that you will want to use a GUI version of vi, such

as gvim. On a Microsoft Windows or macOS

system, this will probably be the default. However, when you run vi

(or some other screen editor of the same vintage) inside a terminal

emulator, it still uses TERM and terminfo and

pays attention to the stty settings. And using it inside a terminal

emulator is just as easy a way to learn vi and Vim as any other.

Another important fact to understand about vi is that it was developed

at a time when Unix systems were considerably less stable than they

are today. The vi user of yesteryear had to be prepared for the

system to crash at arbitrary times, and so vi included support for

recovering files that were in the middle of being edited when the system

crashed.8 So, as you learn vi and Vim and see the descriptions

of various problems that might occur, bear these historical developments in mind.

Opening and Closing Files

You can use vi to edit any text file. The editor copies the file to

be edited into a buffer (an area temporarily set aside in memory),

displays the buffer (though you can see only one screenful at a time),

and lets you add, delete, and change text. When you save your edits,

the editor copies the edited buffer back into a permanent file, replacing

the old file of the same name. Remember that you are always working

on a copy of your file in the buffer, and that your edits do not

affect your original file until you save the buffer. Saving your edits

is also called “writing the buffer,” or more commonly,

“writing your file.”

Opening a File from the Command Line

vim is the Unix command that invokes the Vim editor for an existing

file or for a brand-new file. The syntax for the vim command is:

$vim[filename]

or

$vi[filename]

On modern systems, vi is often just a link to Vim.

The brackets shown on these command lines indicate that the

filename is optional. The brackets should not be typed. The $

is the shell prompt.

If the filename is omitted, the editor opens an unnamed buffer. You can assign the name when you write the buffer into a file. For right now, though, let’s stick to naming the file on the command line.

A filename must be unique inside its directory. (Some operating systems call directories folders; they’re the same thing.)

On Unix systems, a filename can include any 8-bit character except a slash (/), which is reserved as the separator between files and directories in a pathname, and ASCII NUL, the character with all zero bits. You can even include spaces in a filename by typing a backslash (\) before the space. (MS-Windows systems disallow the backslash [\] and the colon [:] character in filenames.) In practice, though, filenames generally consist of any combination of uppercase and lowercase letters, numbers, and the characters dot (.) and underscore (_). Remember that Unix is case sensitive: lowercase letters are distinct from uppercase letters. Also remember that you must press ENTER to tell the shell that you are finished issuing your command.

When you want to open a new file in a directory, give a new filename

with the vi command. For example, if you want to open a new file

called practice in the current directory, you would enter:

$ vi practice

Since this is a new file, the buffer is empty, and the screen appears as follows:

~ ~ ~ "practice" [New file]

The tildes (~) down the lefthand column of the screen indicate that there is no text in the file, not even blank lines. The prompt line (also called the status line) at the bottom of the screen echoes the name and status of the file.

You can also edit any existing text file in a directory by specifying its filename. Suppose that there is a Unix file with the pathname /home/john/letter. If you are already in the /home/john directory, use the relative pathname. For example:

$ vi letter

brings a copy of the file letter to the screen.

If you are in another directory, give the full pathname to begin editing:

$ vi /home/john/letter

Opening a File from the GUI

Although we (strongly) recommend that you become comfortable with the command line, you can run Vim on a file directly from your GUI environment. Typically, you right-click on a file and then select something like “Open with …” from the menu that pops up. If Vim is correctly installed, it will be one of the available options for opening the file.

Usually, you may also start Vim directly from your menuing system, in which case

you then need to tell it which file to edit with the ex command :e filename.

We can’t be any more specific than this, because there are so many different GUI environments in use today.

Problems Opening Files

-

You see one of the following messages:

Visual needs addressable cursor or upline capability

terminal: Unknown terminal type Block device required Not a typewriterYour terminal type is undefined, or else there’s probably something wrong with your

terminfoentry. Enter:qto quit. Often, setting$TERMtovt100is enough to get going, at least in a bare-bones sort of fashion. For further help, you might use an internet search engine or a popular technical questions forum such as Stack Overflow. -

A

[new file]message appears when you think a file already exists.Check that you have used correct case in the filename (Unix filenames are case sensitive). If you have, then you are probably in the wrong directory. Enter

:qto quit. Then check to see that you are in the correct directory for that file (enterpwdat the shell prompt). If you are in the right directory, check the list of files in the directory (withls) to see whether the file exists under a slightly different name. -

You invoke

vibut you get a colon prompt (indicating that you’re inexline-editing mode).You probably typed an interrupt (typically CTRL-C) before

vicould draw the screen. Enterviby typingviat theexprompt (:). -

One of the following messages appears:

[Read only] File is read only Permission denied

“Read only” means that you can only look at the file; you cannot save any changes you make. You may have invoked

viinviewmode (withvieworvi -R), or you do not have write permission for the file. See the section “Opening a File from the Command Line”. -

One of the following messages appears:

Bad file number Block special file Character special file Directory Executable Non-ascii file

filenon-ASCIIThe file you’ve called up to edit is not a regular text file. Type

:q!to quit, and then check the file you wish to edit, perhaps with thefilecommand. -

When you type

:qbecause of one of the previously mentioned difficulties, this message appears:E37: No write since last change (add ! to override)

You have modified the file without realizing it. Type

:q!to leave the editor. Your changes from this session are not saved in the file.

Modus Operandi

As mentioned earlier, the concept of the current “mode”

is fundamental to the way vi works. There are two modes, command

mode and insert mode. (The ex command mode can be considered

a third mode, but we’ll ignore that for now.) You start out in command mode,

where every

keystroke represents a command.9 In insert mode, everything you type

becomes text in your file.

Sometimes, you can accidentally enter insert mode, or conversely, you might leave insert mode accidentally. In either case, what you type will likely affect your files in ways you did not intend.

Press the ESC key to force the editor to enter command mode. If you are already in command mode, the editor beeps at you when you press the ESC key. (Command mode is thus sometimes referred to as “beep mode.”)

Once you are safely in command mode, you can proceed to repair any accidental changes and then continue editing your text. (See the section “Problems with deletions”, and also see the section “Undo”.)

Saving and Quitting a File

You can quit working on a file at any time, save your edits, and return to

the command prompt (if you’re running inside a terminal window).

The command to quit and save edits is ZZ. Note that ZZ is capitalized.

Let’s assume that you do create a file called practice to

practice vi commands, and that you type in six lines of text. To

save the file, first check that you are in command mode by pressing

ESC, and then enter ZZ:

| Keystrokes | Results |

|---|---|

|

"practice" [New] 6L, 104C written |

Give the write and save command, |

|

|

|

Listing the files in the directory shows the new file practice that you created. |

You can also save your edits with ex commands. Type :w to save

(write) your file but not quit; type :q to quit if you

haven’t made any edits; and type :wq to both save your edits

and quit. (:wq is equivalent to ZZ.) We’ll explain fully

how to use ex commands in Chapter 5;

for now, you should just

memorize a few commands for writing and saving files.

Quitting Without Saving Edits

When you are first learning Vim, especially if you are an intrepid

experimenter, there are two other ex commands that are handy for

getting out of any mess that you might create.

What if you want to wipe out all the edits you have made in a session and then reload the original file? The command:

:e! ENTER

reloads the last saved version of the file so you can start over.

Suppose, however, that you want to wipe out your edits and then just quit the editor? The command:

:q! ENTER

immediately quits the file you’re editing and returns you to the command

prompt. With both of these commands, you lose all edits made in the buffer

since the last time you saved the file. The editor normally won’t let

you throw away your edits. The exclamation point added to the :e

or :q command causes it to override this prohibition, performing

the operation even though the buffer has been modified.

Going forward, we don’t show the ENTER

key on ex mode commands, but you must use it to get the editor to

execute them.

Problems Saving Files

-

You try to write your file, but you get one of the following messages:

File exists File

fileexists - use w! [Existing file] File is read onlyType

:w!fileto overwrite the existing file, or type:wnewfileto save the edited version in a new file. -

You want to write a file, but you don’t have write permission for it. You get the message “Permission denied.”

Use

:wnewfileto write out the buffer into a new file. If you have write permission for the directory, you can use themvcommand to replace the original version with your copy of it. If you don’t have write permission for the directory, type:wpathname/fileto write out the buffer to a directory for which you do have write permission (such as your home directory, or /tmp). Be careful not to overwrite any existing files in that directory. -

You try to write your file, but you get a message telling you that the file system is full.

Today, when a 500-gigabyte drive is considered small, errors like this are generally rare. If something like this does occur, you have several courses you can take. First, try to write your file somewhere safe on a different file system (such as /tmp) so that your data is saved. Then try to force the system to save your buffer with the

excommand:pre(short for:preserve). If that doesn’t work, look for some files to remove, as follows:-

Open a graphical file manager (such as Nautilus on GNU/Linux) and try to find old files you don’t need and can remove.

-

Use CTRL-Z to suspend

viand return to the shell prompt. You can then use various Unix commands to try to find large files that are candidates for removal:When done removing files, use

fgto putviback into the foreground; you can then save your work normally.

-

While we’re at it, besides using CTRL-Z

and job control, you should know that you can type :sh to start a new

shell in which to work. Type CTRL-D

or exit to terminate the shell and return to vi. (This even works

from with gvim!)

You can also use something like :!du -s * to run a shell command from

within vi and then return to your editing when the command is done.

Exercises

The only way to learn vi and Vim is to practice. You now know enough to

create a new file and to return to the command prompt. Create a file called

practice, insert some text, and then save and quit the file.

Open a file called practice in the current directory: |

|

Enter insert mode: |

|

Insert text: |

|

Return to command mode: |

ESC |

Quit |

|

1 These days, the term “Unix” includes both commercial systems derived from the original Unix code base and Unix work-alikes whose source code is available. Solaris, AIX, and HP-UX are examples of the former, and GNU/Linux and the various BSD-derived systems are examples of the latter. Also included under this umbrella are macOS’s terminal environment, Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) on MS-Windows, and Cygwin and other similar environments for Windows. Unless otherwise noted, everything in this book applies across the board to all those systems.

2 Perhaps in the same way as Pokémon do?

3 If you don’t have either vi or Vim installed, see Appendix D, “vi and Vim: Source Code and Building”.

4 GNU Emacs has become the universal version of Emacs. The only problem is that it doesn’t come standard with most systems; you must retrieve and install it yourself, even on some GNU/Linux systems.

5 From the use of red pencils to “mark up” changes in typeset galleys or proofs.

6 For more information on these languages, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markdown and http://asciidoc.org, respectively. This book is written in AsciiDoc.

7 troff is for laser printers and typesetters. Its “twin brother” is nroff, for line printers and terminals. Both accept the same input language. Following common Unix convention, we refer to both with the name troff. Today, anyone using troff uses the GNU version, groff.

8 Thankfully, this kind of thing is much less common, although systems can still crash due to external circumstances, such as a power outage. If you have an uninterruptible power supply for your system, or a healthy battery on your laptop, even this worry goes away.

9 Note that vi and Vim do not have commands for every possible key. Rather, in command mode, the editor expects to receive keys representing commands, not text to go into your file. We take advantage of unused keys later, in the section “Using the map Command”.

Get Learning the vi and Vim Editors, 8th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.