Since the early 1970s, when it was first created, the UNIX operating system has become more and more popular. During this time it has branched out into different versions, and taken on such names as Ultrix, AIX, Xenix, SunOS, and Linux. Starting on minicomputers and mainframes, it has moved onto desktop workstations and even personal computers used at work and home. No longer a system used only by academics and computing wizards at universities and research centers, UNIX is used in many businesses, schools, and homes. As time goes on, more people will come into contact with UNIX.

You may have used UNIX at your school, office, or home to run your applications, print documents, and read your electronic mail. But have you ever thought about the process that happens when you type a command and hit RETURN?

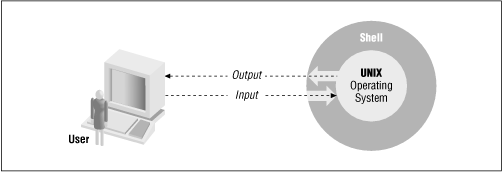

Several layers of events take place whenever you enter a command, but we’re going to consider only the top layer, known as the shell. Generically speaking, a shell is any user interface to the UNIX operating system, i.e., any program that takes input from the user, translates it into instructions that the operating system can understand, and conveys the operating system’s output back to the user. Figure 1.1 shows the relationship between user, shell, and operating system.

There are various types of user interfaces. bash belongs to the most common category, known as character-based user interfaces. These interfaces accept lines of textual commands that the user types in; they usually produce text-based output. Other types of interfaces include the increasingly common graphical user interfaces (GUI), which add the ability to display arbitrary graphics (not just typewriter characters) and to accept input from a mouse or other pointing device, touch-screen interfaces (such as those on some bank teller machines), and so on.

The shell’s job, then, is to translate the user’s command lines into operating system instructions. For example, consider this command line:

sort -n phonelist > phonelist.sorted

This means, “Sort lines in the file phonelist in numerical order, and put the result in the file phonelist.sorted.” Here’s what the shell does with this command:

Breaks up the line into the pieces sort, -n, phone list, >, and phone list.sorted. These pieces are called words.

Determines the purpose of the words: sort is a command, -n and phone list are arguments, and > and phonelist.sorted, taken together, are I/O instructions.

Sets up the I/O according to > phonelist.sorted (output to the file phone list.sorted) and some standard, implicit instructions.

Finds the command sort in a file and runs it with the option -n (numerical order) and the argument phonelist (input filename).

Of course, each of these steps really involves several substeps, each of which includes a particular instruction to the underlying operating system.

Remember that the shell itself is not UNIX—just the user interface to it. UNIX is one of the first operating systems to make the user interface independent of the operating system.

Get Learning the bash Shell, Second Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.