Modules are an integral piece of any robust applicationâs architecture and typically help in keeping the units of code for a project both cleanly separated and organized.

In JavaScript, there are several options for implementing modules. These include:

Object literal notation

The Module pattern

AMD modules

CommonJS modules

ECMAScript Harmony modules

We will be exploring the latter three of these options later on in the book in Chapter 11.

The Module pattern is based in part on object literals, so it makes sense to refresh our knowledge of them first.

In object literal notation, an object is described as a

set of comma-separated name/value pairs enclosed in curly braces

({}). Names inside the object may be either strings or

identifiers that are followed by a colon. There should be no comma used

after the final name/value pair in the object, as this may result in

errors.

varmyObjectLiteral={variableKey:variableValue,functionKey:function(){// ...};};

Object literals donât require instantiation using the new operator, but shouldnât be used at the

start of a statement, as the opening { may be interpreted as the beginning of a

block. Outside of an object, new members may be added to the object

literal using assignment as follows: myModule.property = "someValue";

Below, we can see a more complete example of a module defined using object literal notation:

varmyModule={myProperty:"someValue",// object literals can contain properties and methods.// e.g we can define a further object for module configuration:myConfig:{useCaching:true,language:"en"},// a very basic methodmyMethod:function(){console.log("Where in the world is Paul Irish today?");},// output a value based on the current configurationmyMethod2:function(){console.log("Caching is:"+(this.myConfig.useCaching)?"enabled":"disabled");},// override the current configurationmyMethod3:function(newConfig){if(typeofnewConfig==="object"){this.myConfig=newConfig;console.log(this.myConfig.language);}}};// Outputs: Where in the world is Paul Irish today?myModule.myMethod();// Outputs: enabledmyModule.myMethod2();// Outputs: frmyModule.myMethod3({language:"fr",useCaching:false});

Using object literals can assist in encapsulating and organizing your code. Rebecca Murphey has previously written about this topic in depth, should you wish to read into object literals further.

That said, if weâre opting for this technique, we may be equally as interested in the Module pattern. It still uses object literals but only as the return value from a scoping function.

The Module pattern was originally defined as a way to provide both private and public encapsulation for classes in conventional software engineering.

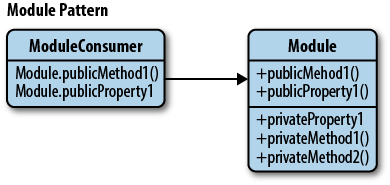

In JavaScript, the Module pattern is used to further emulate the concept of classes in such a way that weâre able to include both public/private methods and variables inside a single object, thus shielding particular parts from the global scope. What this results in is a reduction in the likelihood of our function names conflicting with other functions defined in additional scripts on the page (Figure 9-2).

The Module pattern encapsulates âprivacyâ state and organization using closures. It provides a way of wrapping a mix of public and private methods and variables, protecting pieces from leaking into the global scope and accidentally colliding with another developerâs interface. With this pattern, only a public API is returned, keeping everything else within the closure private.

This gives us a clean solution for shielding logic doing the heavy lifting while only exposing an interface we would like other parts of our application to use. The pattern is quite similar to an immediately-invoked functional expression[1] , except that an object is returned rather than a function.

It should be noted that there isnât really an explicitly true sense of âprivacyâ inside JavaScript because unlike some traditional languages, it doesnât have access modifiers. Variables canât technically be declared as being public nor private, and so we use function scope to simulate this concept. Within the Module pattern, variables or methods declared are only available inside the module itself, thanks to closure. Variables or methods defined within the returning object, however, are available to everyone.

From a historical perspective, the Module pattern was originally developed by a number of people, including Richard Cornford in 2003. It was later popularized by Douglas Crockford in his lectures. In addition, if youâve ever played with Yahooâs YUI library, some of its features may appear quite familiar, because the Module pattern was a strong influence for YUI when creating their components.

Letâs begin looking at an implementation of the Module pattern by creating a module that is self-contained.

vartestModule=(function(){varcounter=0;return{incrementCounter:function(){return++counter;},resetCounter:function(){console.log("counter value prior to reset: "+counter);counter=0;}};})();// Usage:// Increment our countertestModule.incrementCounter();// Check the counter value and reset// Outputs: 1testModule.resetCounter();

Here, other parts of the code are unable to directly read the

value of our incrementCounter() or

resetCounter(). The

counter variable is actually fully shielded from

our global scope so it acts just like a private variable wouldâits

existence is limited to within the moduleâs closure so that the only

code able to access its scope, are our two functions. Our methods are

effectively namespaced so in the test section of our code, we need to

prefix any calls with the name of the module (e.g.,

testModule).

When working with the Module pattern, we may find it useful to define a simple template for getting started with it. Hereâs one that covers namespacing, public, and private variables:

varmyNamespace=(function(){// A private counter variablevarmyPrivateVar=0;// A private function which logs any argumentsvarmyPrivateMethod=function(foo){console.log(foo);};return{// A public variablemyPublicVar:"foo",// A public function utilizing privatesmyPublicFunction:function(bar){// Increment our private countermyPrivateVar++;// Call our private method using barmyPrivateMethod(bar);}};})();

Looking at another example, we can see a shopping basket

implemented using this pattern. The module itself is completely

self-contained in a global variable called basketModule. The basket array in the module is kept private,

so other parts of our application are unable to directly read it. It

only exists with the moduleâs closure, so the only methods able to

access it are those with access to its scope (i.e., addItem(), getItem(), etc.).

varbasketModule=(function(){// privatesvarbasket=[];functiondoSomethingPrivate(){//...}functiondoSomethingElsePrivate(){//...}// Return an object exposed to the publicreturn{// Add items to our basketaddItem:function(values){basket.push(values);},// Get the count of items in the basketgetItemCount:function(){returnbasket.length;},// Public alias to a private functiondoSomething:doSomethingPrivate,// Get the total value of items in the basketgetTotal:function(){varitemCount=this.getItemCount(),total=0;while(itemCount--){total+=basket[itemCount].price;}returntotal;}};}());

Inside the module, you may have noticed that we return an

object. This gets automatically

assigned to basketModule so that we

can interact with it as follows:

// basketModule returns an object with a public API we can usebasketModule.addItem({item:"bread",price:0.5});basketModule.addItem({item:"butter",price:0.3});// Outputs: 2console.log(basketModule.getItemCount());// Outputs: 0.8console.log(basketModule.getTotal());// However, the following will not work:// Outputs: undefined// This is because the basket itself is not exposed as a part of our// the public APIconsole.log(basketModule.basket);// This also won't work as it only exists within the scope of our// basketModule closure, but not the returned public objectconsole.log(basket);

The methods above are effectively namespaced inside basketModule.

Notice how the scoping function in the above basket module is wrapped around all of our functions, which we then call and immediately store the return value of. This has a number of advantages including:

The freedom to have private functions that can only be consumed by our module. As they arenât exposed to the rest of the page (only our exported API is), theyâre considered truly private.

Given that functions are declared normally and are named, it can be easier to show call stacks in a debugger when weâre attempting to discover what function(s) threw exceptions.

As T.J. Crowder has pointed out in the past, it also enables us to return different functions depending on the environment. In the past, Iâve seen developers use this to perform UA testing to provide a codepath in their module specific to IE, but we can easily opt for feature detection these days to achieve a similar goal.

This variation of the pattern demonstrates how globals

(e.g., jQuery,

Underscore) can be passed in as arguments to our

moduleâs anonymous function. This effectively allows us to

import them and locally alias them as we

wish.

// Global modulevarmyModule=(function(jQ,_){functionprivateMethod1(){jQ(".container").html("test");}functionprivateMethod2(){console.log(_.min([10,5,100,2,1000]));}return{publicMethod:function(){privateMethod1();}};// Pull in jQuery and Underscore}(jQuery,_));myModule.publicMethod();

This next variation allows us to declare globals without consuming them and could similarly support the concept of global imports seen in the last example.

// Global modulevarmyModule=(function(){// Module objectvarmodule={},privateVariable="Hello World";functionprivateMethod(){// ...}module.publicProperty="Foobar";module.publicMethod=function(){console.log(privateVariable);};returnmodule;}());

Dojo provides a convenience method for working with objects

called dojo.setObject(). This

takes as its first argument a dot-separated string such as myObj.parent.child, which refers to a

property called child within an object

parent defined inside myObj.

Using setObject() allows us to

set the value of children, creating any of the intermediate objects

in the rest of the path passed if they donât already exist.

For example, if we wanted to declare basket.core as an object of the store namespace, this could be achieved as

follows using the traditional way:

varstore=window.store||{};if(!store["basket"]){store.basket={};}if(!store.basket["core"]){store.basket.core={};}store.basket.core={// ...rest of our logic};

Or as follows using Dojo 1.7 (AMD-compatible version) and above:

require(["dojo/_base/customStore"],function(store){// using dojo.setObject()store.setObject("basket.core",(function(){varbasket=[];functionprivateMethod(){console.log(basket);}return{publicMethod:function(){privateMethod();}};}()));});

For more information on dojo.setObject(), see the official documentation.

For those using Senchaâs ExtJS, youâre in for some luck, as the official documentation incorporates examples that demonstrate how to correctly use the Module pattern with the framework.

Here we can see an example of how to define a namespace that can then be populated with a module containing both a private and public API. With the exception of some semantic differences, itâs quite close to how the Module pattern is implemented in vanilla JavaScript:

// create namespaceExt.namespace("myNameSpace");// create applicationmyNameSpace.app=function(){// do NOT access DOM from here; elements don't exist yet// private variablesvarbtn1,privVar1=11;// private functionsvarbtn1Handler=function(button,event){console.log("privVar1",privVar1);console.log("this.btn1Text="+this.btn1Text);};// public spacereturn{// public properties, e.g. strings to translatebtn1Text:"Button 1",// public methodsinit:function(){if(Ext.Ext2){btn1=newExt.Button({renderTo:"btn1-ct",text:this.btn1Text,handler:btn1Handler});}else{btn1=newExt.Button("btn1-ct",{text:this.btn1Text,handler:btn1Handler});}}};}();

Similarly, we can implement the Module pattern when building applications using YUI3. The following example is heavily based on the original YUI Module pattern implementation by Eric Miraglia, but again, isnât vastly different from the vanilla JavaScript version:

Y.namespace("store.basket")=(function(){varmyPrivateVar,myPrivateMethod;// private variables:myPrivateVar="I can be accessed only within Y.store.basket.";// private method:myPrivateMethod=function(){Y.log("I can be accessed only from within YAHOO.store.basket");}return{myPublicProperty:"I'm a public property.",myPublicMethod:function(){Y.log("I'm a public method.");// Within basket, I can access "private" vars and methods:Y.log(myPrivateVar);Y.log(myPrivateMethod());// The native scope of myPublicMethod is store so we can// access public members using "this":Y.log(this.myPublicProperty);}};})();

There are a number of ways in which jQuery code unspecific to plug-ins can be wrapped inside the Module pattern. Ben Cherry previously suggested an implementation in which a function wrapper is used around module definitions in the event of there being a number of commonalities between modules.

In the following example, a library function is defined that declares a new library and

automatically binds up the init

function to document.ready when

new libraries (i.e., modules) are created.

functionlibrary(module){$(function(){if(module.init){module.init();}});returnmodule;}varmyLibrary=library(function(){return{init:function(){// module implementation}};}());

Weâve seen why the Singleton pattern can be useful, but why is the Module pattern a good choice? For starters, itâs a lot cleaner for developers coming from an object-oriented background than the idea of true encapsulation, at least from a JavaScript perspective.

Second, it supports private dataâso, in the Module pattern, public parts of our code are able to touch the private parts, however the outside world is unable to touch the classâs private parts (thanks to David Engfer for the joke).

The disadvantages of the Module pattern are that, as we access both public and private members differently, when we wish to change visibility, we actually have to make changes to each place the member was used.

We also canât access private members in methods that are added to the object at a later point. That said, in many cases, the Module pattern is still quite useful and, when used correctly, certainly has the potential to improve the structure of our application.

Other disadvantages include the inability to create automated unit tests for private members and additional complexity when bugs require hot fixes. Itâs simply not possible to patch privates. Instead, one must override all public methods that interact with the buggy privates. Developers canât easily extend privates either, so itâs worth remembering privates are not as flexible as they may initially appear.

For further reading on the Module pattern, see Ben Cherryâs excellent in-depth article.

Get Learning JavaScript Design Patterns now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.