In the previous chapter, we described most of the components that Swing offers for building user interfaces. In this chapter, you’ll find out about the rest. These include Swing’s text components, trees, and tables. These types of components have considerable depth, but are quite easy to use if you accept their default options. We’ll show you the easy way to use these components, and start to describe the more advanced features of each. The chapter ends with a brief description of how to implement your own components in Swing.

Swing gives us sophisticated text components, from plain text entry boxes to HTML interpreters. For full coverage of Swing’s text capabilities, see Java Swing, by Robert Eckstein, Marc Loy, and Dave Wood (O’Reilly & Associates). In that encyclopedic book, six meaty chapters are devoted to text. It’s a huge subject; we’ll just scratch the surface here.

Let’s begin by examining the simpler text components:

JTextArea

is a multiline text editor;

JTextField is a simple, single-line text editor.

Both JTextField and JTextArea

derive from the

JTextComponent

class, which provides the functionality

they have in common. This includes methods for setting and retrieving

the displayed text, specifying whether the text is

“editable” or read-only, manipulating the cursor position

within the text, and manipulating text selections.

Observing changes in text components requires an understanding of how

the components implement the

Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture.

You may recall from the last chapter that Swing components implement

a true MVC architecture. It’s in the text components that you

first get an inkling of a clear separation between the M and VC parts

of the MVC architecture. The model for text components is an object

called a Document

. When you add or remove text from a

JTextField or a JTextArea, the

corresponding Document is changed. It’s the

document itself, not the visual components, that generates text

events when something changes. To receive notification of

JTextArea changes, therefore, you register with

the underlying Document, not with the

JTextArea component itself:

JTextArea textArea = new JTextArea( ); Document d = textArea.getDocument( ); d.addDocumentListener(someListener);

As you’ll see in an upcoming example, you can easily have more

than one visual text component use the same underlying data model, or

Document.

In addition, JTextField components generate an

ActionEvent whenever the user presses the Return

key within the field. To get these events, implement the

ActionListener interface, and call

addActionListener( ) to register.

The next sections contain a couple of simple applications that show you how to work with text areas and fields.

Our first example, TextEntryBox

, creates a JTextArea

and ties it to a JTextField, as you can see in

Figure 15.1. When the user hits Return in the

JTextField, we receive an

ActionEvent and add the line to the

JTextArea’s display. Try it out. You may

have to click your mouse in the JTextField to give

it focus before typing in it. If you fill up the display with lines,

you can test drive the scrollbar:

//file: TextEntryBox.java

import java.awt.*;

import java.awt.event.*;

import javax.swing.*;

public class TextEntryBox extends JFrame {

public TextEntryBox( ) {

super("TextEntryBox v1.0");

setSize(200, 300);

setLocation(200, 200);

final JTextArea area = new JTextArea( );

area.setFont(new Font("Serif", Font.BOLD, 18));

area.setText("Howdy!\n");

final JTextField field = new JTextField( );

Container content = getContentPane( );

content.add(new JScrollPane(area), BorderLayout.CENTER);

content.add(field, BorderLayout.SOUTH);

setVisible(true);

field.requestFocus( );

field.addActionListener(new ActionListener( ) {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent ae) {

area.append(field.getText( ) + '\n');

field.setText("");

}

});

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

JFrame f = new TextEntryBox( );

f.addWindowListener(new WindowAdapter( ) {

public void windowClosing(WindowEvent we) { System.exit(0); }

});

f.setVisible(true);

}

}

TextEntryBox is

exceedingly simple; we’ve done a few things to make it more

interesting. We give the text area a bigger font using

Component

’s setFont( )

method; fonts are discussed in Chapter 17. Finally,

we want to be notified whenever the user presses Return in the text

field, so we register an anonymous inner class as a listener for

action events.

Pressing Return in the JTextField generates an

action event, and that’s where the fun begins. We handle the

event in the actionPerformed( ) method of our

inner ActionListener

implementation.

Then we use the getText( ) and setText( ) methods to manipulate

the text the user has typed. These methods can be used for both

JTextField and JTextArea,

because these components are derived from the

JTextComponent class, and therefore have some

common functionality.

The event handler, actionPerformed( ), calls

field.getText( ) to read the text that the user

typed into our JTextField. It then adds this text

to the JTextArea by calling area.append( ). Finally, we clear the text field by calling the method

field.setText(""), preparing it for more input.

Remember, the text components really are distinct from the text data

model, the Document. When you call

setText( ), getText( ), or

append( ), these methods are shorthand for

operations on an underlying Document.

By default, JTextField and

JTextArea are editable; you can type and edit in

both text components. They can be changed to output-only areas by

calling setEditable(false). Both text components

also support selections. A selection is a range

of text that is highlighted for copying and pasting in your windowing

system. You select text by dragging the mouse over it; you can then

copy and paste it into other text windows. The current text selection

is returned by getSelected-Text( )

.

Notice how JTextArea fits neatly inside a

JScrollPane

. The scroll pane gives us the expected

scrollbars and scrolling behavior if the text in the

JTextArea becomes too large for the available

space.

Swing includes a class just for typing

passwords, called

JPasswordField. A

JPasswordField behaves just like a

JTextField (it’s a subclass), except every

character that’s typed is echoed as a single

character, typically an asterisk.

Figure 15.2 shows the option dialog example

that was presented in Chapter 14. The example

includes a JTextField and a

JPasswordField.

The creation and use of JPasswordField is

basically the same as for JTextField. If you find

asterisks distasteful, you can tell the

JPasswordField to use a different character using

the setEchoChar( )

method.

Normally, you would use getText( ) to retrieve the

text typed into the JPasswordField. This method,

however, is deprecated; you should use getPassword( )

instead. The

getPassword( ) method returns a character array

rather than a String object. This is done because

character arrays are less vulnerable than Strings

to discovery by memory-snooping password sniffer programs. If

you’re not that concerned, you can simply create a new

String from the character array. Note that methods

in the Java cryptographic classes accept passwords as character

arrays, not strings, so it makes a lot of sense to pass the results

of a getPassword( ) call directly to methods in

the cryptographic classes, without ever creating a

String.

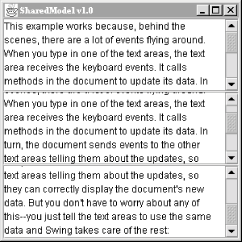

Our next example shows how easy it is to make two or more

text components share the same

Document; Figure 15.3 shows

what the application looks like. Anything the user types into any

text area is reflected in all of them. All we had to do is make all

the text areas use the same data model, like this:

JTextArea areaFiftyOne = new JTextArea( ); JTextArea areaFiftyTwo = new JTextArea( ); areaFiftyTwo.setDocument(areaFiftyOne.getDocument( )); JTextArea areaFiftyThree = new JTextArea( ); areaFiftyThree.setDocument(areaFiftyOne.getDocument( ));

We could just as easily make seven text areas sharing the same document, or seventy. While this example may not look very useful, keep in mind that you can scroll different text areas to different places in the same document. That’s one of the beauties of putting multiple views on the same data—you get to examine different parts of it. Another useful technique is viewing the same data in different ways. You could, for example, view some tabular numerical data as both a spreadsheet and a pie chart. The MVC architecture that Swing uses means that it’s possible to do this in an intelligent way, so that if numbers in a spreadsheet are updated, a pie chart that uses the same data will automatically be updated also.

This example works because behind the scenes, there are a lot of events flying around. When you type in one of the text areas, the text area receives the keyboard events. It calls methods in the document to update its data. In turn, the document sends events to the other text areas telling them about the updates, so they can correctly display the document’s new data. But you don’t have to worry about any of this—you just tell the text areas to use the same data and Swing takes care of the rest:

//file: SharedModel.java

import java.awt.*;

import java.awt.event.*;

import javax.swing.*;

public class SharedModel extends JFrame {

public SharedModel( ) {

super("SharedModel v1.0");

setSize(300, 300);

setLocation(200, 200);

JTextArea areaFiftyOne = new JTextArea( );

JTextArea areaFiftyTwo = new JTextArea( );

areaFiftyTwo.setDocument(areaFiftyOne.getDocument( ));

JTextArea areaFiftyThree = new JTextArea( );

areaFiftyThree.setDocument(areaFiftyOne.getDocument( ));

Container content = getContentPane( );

content.setLayout(new GridLayout(3, 1));

content.add(new JScrollPane(areaFiftyOne));

content.add(new JScrollPane(areaFiftyTwo));

content.add(new JScrollPane(areaFiftyThree));

setVisible(true);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

JFrame f = new SharedModel( );

f.addWindowListener(new WindowAdapter( ) {

public void windowClosing(WindowEvent we) { System.exit(0); }

});

f.setVisible(true);

}

}Setting up the display is simple. We use a

GridLayout (discussed in the next chapter) and add

three text areas to the layout. Then all we have to do is tell the

text areas to use the same Document.

Most user interfaces will use only two subclasses of

JTextComponent. These are the simple

JTextField and JTextArea

classes that we just covered. That’s just the tip of the

iceberg, however. Swing offers sophisticated text capabilities

through two other subclasses of

JTextComponent:

JEditorPane and JTextPane.

The first of these, JEditorPane, can display

HTML and RTF documents. It also

fires one more type of event, a

HyperlinkEvent

. Subtypes of this event are fired off

when the mouse enters, exits, or clicks on a hyperlink. Combined with

JEditorPane’s HTML display capabilities,

it’s very easy to build a simple

browser. Here’s one in fewer than 100

lines:

//file: CanisMinor.java

import java.awt.*;

import java.awt.event.*;

import java.net.*;

import javax.swing.*;

import javax.swing.event.*;

public class CanisMinor extends JFrame {

protected JEditorPane mEditorPane;

protected JTextField mURLField;

public CanisMinor(String urlString) {

super("CanisMinor v1.0");

createUI(urlString);

setVisible(true);

}

protected void createUI(String urlString) {

setSize(500, 600);

center( );

Container content = getContentPane( );

content.setLayout(new BorderLayout( ));

// add the URL control

JToolBar urlToolBar = new JToolBar( );

mURLField = new JTextField(urlString, 40);

urlToolBar.add(new JLabel("Location:"));

urlToolBar.add(mURLField);

content.add(urlToolBar, BorderLayout.NORTH);

// add the editor pane

mEditorPane = new JEditorPane( );

mEditorPane.setEditable(false);

content.add(new JScrollPane(mEditorPane), BorderLayout.CENTER);

// open the initial URL

openURL(urlString);

// go to a new location when enter is pressed in the URL field

mURLField.addActionListener(new ActionListener( ) {

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent ae) {

openURL(ae.getActionCommand( ));

}

});

// add the plumbing to make links work

mEditorPane.addHyperlinkListener(new LinkActivator( ));

// exit the application when the window is closed

addWindowListener(new WindowAdapter( ) {

public void windowClosing(WindowEvent e) { System.exit(0); }

});

}

protected void center( ) {

Dimension screen = Toolkit.getDefaultToolkit().getScreenSize( );

Dimension us = getSize( );

int x = (screen.width - us.width) / 2;

int y = (screen.height - us.height) / 2;

setLocation(x, y);

}

protected void openURL(String urlString) {

try {

URL url = new URL(urlString);

mEditorPane.setPage(url);

mURLField.setText(url.toExternalForm( ));

}

catch (Exception e) {

System.out.println("Couldn't open " + urlString + ":" + e);

}

}

class LinkActivator implements HyperlinkListener {

public void hyperlinkUpdate(HyperlinkEvent he) {

HyperlinkEvent.EventType type = he.getEventType( );

if (type == HyperlinkEvent.EventType.ENTERED)

mEditorPane.setCursor(

Cursor.getPredefinedCursor(Cursor.HAND_CURSOR));

else if (type == HyperlinkEvent.EventType.EXITED)

mEditorPane.setCursor(Cursor.getDefaultCursor( ));

else if (type == HyperlinkEvent.EventType.ACTIVATED)

openURL(he.getURL().toExternalForm( ));

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

String urlString = "http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/java2d/";

if (args.length > 0)

urlString = args[0];

new CanisMinor(urlString);

}

}This browser is shown in Figure 15.4.

JEditorPane

is the center of this little application.

Passing a URL to setPage( ) causes the

JEditorPane to load a new page, either from a

local file or from somewhere across the Internet. To go to a new

page, enter it in the text field at the top of the window and press

Return. This fires an ActionEvent which sets the

new page location of the JEditorPane. It can

display RTF files, too. (RTF is the text or non-binary storage format

for Microsoft Word documents.)

Responding to

hyperlinks correctly is simply a matter of

responding to the HyperlinkEvents thrown by the

JEditorPane. This behavior is encapsulated in the

LinkActivator inner class. If the mouse enters a

hyperlink area, the cursor is changed to a hand. It’s changed

back when the mouse exits a hyperlink. If the user

“activates” the hyperlink by clicking on it, we set the

location of the JEditorPane to the location given

under the hyperlink. Surf away!

Behind the scenes, something called an

EditorKit

handles displaying documents for the

JEditorPane. Different kinds of

EditorKits are used to display different kinds of

documents. For HTML, the HTMLEditorKit class (in

the javax.swing.text.html package) handles the

display. Currently, this class supports HTML 3.2. Subsequent releases

of the SDK will contain enhancements to the capabilities of

HTMLEditorKit; eventually, it will support HTML

4.0.

There’s another component here that we haven’t covered

before—the

JToolBar

. This nifty container houses our URL text

field. Initially, the JToolBar starts out at the

top of the window. But you can pick it up by clicking on the little

dotted box near its left edge, then drag it around to different parts

of the window. You can place this toolbar at the top, left, right, or

bottom of the window, or you can drag it outside the window entirely.

It will then inhabit a window of its own. All this behavior comes for

free from the JToolBar class. All we had to do was

create a JToolBar and add some components to it.

The JToolBar is just a container, so we add it to

the content pane of our window to give it an initial location.

Swing offers one last subclass of

JTextComponent that can do just about anything you

want: JTextPane. The basic text components,

JTextField and JTextArea, are

limited to a single font in a single style. But

JTextPane, a subclass of

JEditorPane, can display multiple fonts and

multiple styles in the same component. It also includes support for a

cursor (caret), highlighting, image embedding, and other advanced

features.

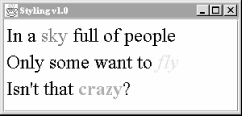

We’ll just take a peek at JTextPane here by

creating a text pane with some styled text. Remember, the text itself

is stored in an underlying data model, the

Document

. To create styled text, we simply

associate a set of text

attributes with different parts of the document’s

text. Swing includes classes and methods for manipulating sets of

attributes, like specifying a bold font or a different color for the

text. Attributes themselves are contained in a class called

SimpleAttributeSet

; these attribute sets are manipulated

with static methods in the StyleConstants class.

For example, to create a set of

attributes that specifies the color red, you could do this:

SimpleAttributeSet redstyle = new SimpleAttributeSet( ); StyleConstants.setForeground(redstyle, Color.red);

To add some red text to a document, you would just pass the text and

the attributes to the document’s insertString( )

method, like this:

document.insertString(6, "Some red text", redstyle);

The first argument to insertString( ) is an offset

into the text. An exception is thrown if you pass in an offset

that’s greater than the current length of the document. If you

pass null for the attribute set, the text is added

in the JTextPane’s default font and style.

Our simple example creates several attribute sets and uses them to

add plain and styled text to a

JTextPane

, as shown in Figure 15.5.

//file: Styling.java

import java.awt.*;

import java.awt.event.*;

import javax.swing.*;

import javax.swing.text.*;

public class Styling extends JFrame {

private JTextPane textPane;

public Styling( ) {

super("Styling v1.0");

setSize(300, 200);

setLocation(200, 200);

textPane = new JTextPane( );

textPane.setFont(new Font("Serif", Font.PLAIN, 24));

// create some handy attribute sets

SimpleAttributeSet red = new SimpleAttributeSet( );

StyleConstants.setForeground(red, Color.red);

StyleConstants.setBold(red, true);

SimpleAttributeSet blue = new SimpleAttributeSet( );

StyleConstants.setForeground(blue, Color.blue);

SimpleAttributeSet italic = new SimpleAttributeSet( );

StyleConstants.setItalic(italic, true);

StyleConstants.setForeground(italic, Color.orange);

// add the text

append("In a ", null);

append("sky", blue);

append(" full of people\nOnly some want to ", null);

append("fly", italic);

append("\nIsn't that ", null);

append("crazy", red);

append("?", null);

Container content = getContentPane( );

content.add(new JScrollPane(textPane), BorderLayout.CENTER);

setVisible(true);

}

protected void append(String s, AttributeSet attributes) {

Document d = textPane.getDocument( );

try { d.insertString(d.getLength( ), s, attributes); }

catch (BadLocationException ble) {}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

JFrame f = new Styling( );

f.addWindowListener(new WindowAdapter( ) {

public void windowClosing(WindowEvent we) { System.exit(0); }

});

f.setVisible(true);

}

}This example creates a JTextPane, which is saved

away in a member variable. Three different attribute sets are

created, using combinations of text styles and foreground colors.

Then, using a helper method called append( )

, text

is added to the JTextPane.

The append( ) method tacks a text

String on the end of the

JTextPane’s document, using the supplied

attributes. Remember that if the attributes are

null, the text is displayed with the

JTextPane’s default font and style.

You can go ahead and add your own text, if you wish. If you place the

caret inside one of the differently styled words and type, the new

text comes out in the appropriate style. Pretty cool, eh?

You’ll also notice that JTextPane gives us

word-wrapping behavior for free. And since we’ve wrapped the

JTextPane in a JScrollPane, we

get scrolling for free, too. Swing allows you to do some really cool

stuff without breaking a sweat. Just wait—there’s plenty

more to come.

This simple example should give you some idea of what

JTextPane can do. It’s reasonably easy to

build a simple word processor with JTextPane, and

complex commercial-grade word processors are definitely possible.

If JTextPane still isn’t good enough for

you, or you need some finer control over character, word, and

paragraph layout, you can actually draw text, carets, and highlight

shapes yourself. A class in the 2D API called

TextLayout

simplifies much of this work, but

it’s outside the scope of this book. For coverage of

TextLayout and other advanced text

drawing topics,

see Java 2D Graphics by Jonathan Knudsen

(O’Reilly & Associates).

Get Learning Java now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.