After all of that narrative, you're no doubt ready to see some code in action. This section provides a series of increasingly complex "HelloWorld" examples that demonstrate fundamental concepts involved in custom dijit design.

Let's build a canonical HelloWorld dijit and take a closer look at some of the issues we've discussed. Although this section focuses exclusively on what seems like such a simple dijit, you'll find that there are several intricacies that we'll highlight that are common to developing any dijit.

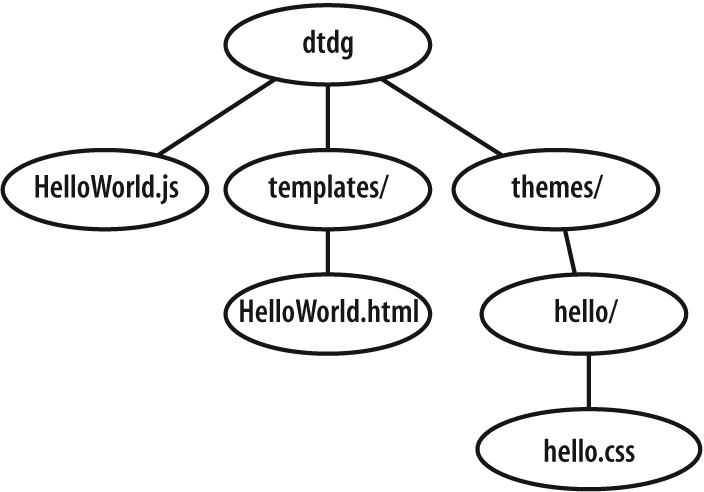

Figure 12-2 illustrates the basic layout of the HelloWorld dijit as it appears on disk. There are no tricks involved; this is a direct instantiation of the generic layout presented earlier.

The first take on the HelloWorld dijit provides the full body of each component. For brevity and clarity, subsequent iterations provide only relevant portions of components that are directly affected from changes. As far as on disk layout, these examples assume that the main HTML file that includes the widgets is located alongside a dtdg module directory that contains the widget code.

First, let's take a look at the HTML page that will contain the dijit, shown in Example 12-2. Verbose commenting is inline and should be fairly self-explanatory.

Example 12-2. HelloWorld (Take 1)

<html>

<head>

<title>Hello World, Take 1</title>

<!--

Because Dojo is being served from AOL's server, we have to provide a

couple of extra configuration options in djConfig as the XDomain

build (dojo.xd.js) gets loaded.

Thus, we associate the "dtdg" namespace w/ a particular relative path

on disk by specifying a baseUrl along with a collection of namespace mappings.

If we were using a local copy of Dojo, we could simply stick the

dtdg directory beside the dojo directory and it would have been

found automatically.

Specifying that dijits on the page should be parsed on page load

is normally standard for any situation in which you have dojoType tags in the page.

-->

<script

type="text/javascript"

src="http://o.aolcdn.com/dojo/1.1/dojo/dojo.xd.js"

djConfig=isDebug:true,parseOnLoad:true,baseUrl:'./',modulePaths:{dtdg:'dtdg'}">

</script>

<!--

You'll normally include the dojo.css file, followed by

any of your own specific style sheets. Remember that if you're not using

AOL's XDomain build, you'll want to point to your own local dojo.css file.

-->

<link

rel="stylesheet"

type="text/css"

href="http://o.aolcdn.com/dojo/1.1/dojo/resources/dojo.css">

</link>

<link

rel="stylesheet"

type="text/css"

href="dtdg/themes/hello/hello.css">

</link>

<script type="text/javascript">

dojo.require("dojo.parser");

//Tell Dojo to fetch a dijit called HelloWorld that's associated

//with the dtdg namespace so that we can use it in the body.

//Dojo will use the values in djConfig.modulePaths to look up the location.

dojo.require("dtdg.HelloWorld");

</script>

</head>

<body>

<!--

This is where the Dojo parser swaps in the dijit from the

dojo.require statement based on our parseOnLoad:true option.

Any styles applied to the dijit are provided by the style sheets imported.

-->

<div dojoType="dtdg.HelloWorld"></div>

</body>

</html>What you just saw is almost the bare minimum that would

appear in any page that contains a dijit. There is a token

reference to any relevant style sheets that are spiffing up the

dijits, the customary reference to Base that bootstraps Dojo, and

then we explicitly dojo.require

in the parser and HelloWorld dijit we're using in the body of the

page. The only remotely tricky thing about any of these things is

properly mapping the dtdg

module to its path on disk in djConfig.modulePaths.

A widget's style consists of ordinary CSS and any static

support that may be necessary, such as images. The neat thing,

however, is that the actual style for the dijit is reflected in

the dijit template—not in the DOM element where the dojoType tag is specified. This is

particularly elegant because it essentially makes your dijits

skinnable, or in Dojo parlance, you can define

themes for your dijits and change these

themes by swapping out stylesheets.

In our example dijit, the style for an individual DIV element is purely pedagogical but

does illustrate how you could style your own dijits. Our

HelloWorld theme consists of a single CSS file with nothing more

than the following style in it:

div.hello_class {

color: #009900;

}Just like the style, our HTML template for the HelloWorld is

minimal. We're simply telling Dojo to take the DIV tag that was specified in our HTML

page and swap it out with whatever our template supplies—in this

case, our template just happens to supply another DIV element with some style and inner

text that says "Hello World".

Our actual template file contains nothing more than the following line of HTML:

<div class="hello_class">Hello World</div>

Although it looks like there's an awful lot going on in the JavaScript, most of the substance is simply extra-verbose commenting. We're still dealing with the basic constructs that have already been reviewed, and you'll see that it's actually pretty simple. Go ahead and have a look, and then we'll recap on the other end. As you'll notice, the JavaScript file is just a standard module:

//Summary: An example HelloWorld dijit that illustrates Dojo's basic dijit

//design pattern

//The first line of any module file should have exactly one dojo.provide

//specifying the resource and any membership in parent modules. The name

//of the resource should be the same as the .js file.

dojo.provide("dtdg.HelloWorld");

//Always require resources before you try to use them. We're requiring these

//two resources because they're part of our dijit's inheritance hierarchy.

dojo.require("dijit._Widget");

dojo.require("dijit._Templated");

//The feature rich constructor that allows us to declare Dojo "classes".

dojo.declare(

"dtdg.HelloWorld",

//dijit._Widget is the prototypical ancestor that provides important method

//stubs like the ones below.

//dijit._Templated is then mixed in and overrides dijit._Widget's

//buildRendering method, which constructs the UI for the dijit from

//a template.

[dijit._Widget, dijit._Templated],

{

//Path to the template of this dijit. dijit._Templated uses this to

//snatch the template from the named file via a synchronous call.

templatePath: dojo.moduleUrl("dtdg", "templates/HelloWorld.html")

}

);In the inheritance chain, _Widget provides the prototypical

ancestor that our dijit inherits from to become a dijit. Because

this first example is minimalist, we didn't need to override any

of _Widget 's lifecycle

methods, but examples that override these methods are coming up.

The mixin ancestor, _Templated,

provides functionality that pulls in the template by overriding

_Widget.buildRendering. The

actual template was located via the templatePath property. Although using

templatePath instead of

templateString incurred the

overhead of a synchronous call back to the server, the template

gets cached after it has been retrieved. Therefore, another

synchronous call would not be necessary if another HelloWorld

dijit came to exist in the same page.

Tip

The first time Dojo fetches a template file for a dijit, the overhead of a synchronous call back to the server is incurred. Afterward, the template gets cached.

Although this example entails your screen simply displaying

a message to the screen, there's a lot more than a print statement behind the scenes that

makes this happen. Moreover, the effort involved in HelloWorld is

pretty much the minimal amount of effort that would ever be

required of any dijit.

Let's solidify your understanding a bit more by filling in some of the method stubs to enhance the dijit. Only instead of taking the direct route, we'll take a few detours. After all, what better way to learn?

Suppose you want your dijit to be a little less generic.

Instead of displaying the same static message every time the page is

loaded, a good first step might be to make the custom message that

is displayed dynamic. One of the wonderful mechanisms that Dojo

employs for keeping the logical concept of a dijit cohesive is that

you can reference dijit properties that are defined in your

JavaScript source file inside the template. Although referencing

dijit properties from inside the template is only useful prior to

_Templated 's buildRendering method executing, you'll

find that initializing some portion of a dijit's display before it

appears on the screen is a very common operation.

Referencing a dijit property from inside of the template file is simple. Consider the following revision to the HelloWorld template file:

<div class="hello_class">${greeting}

</div>In short, you can refer to any property of the dijit that

exists from inside of the template file and use it to manipulate the

initial display, style, etc. However, there is a small but

incredibly important catch: you have to do it at the right time. In

particular, dijit properties that are referenced in templates are

almost always most appropriately manipulated in the postMixInProperties method. Recall that

postMixInProperties is called

before buildRendering, which is

the point at which your dijit gets inserted into the DOM and becomes

visible.

Warning

Recall that the canonical location to manipulate template

strings is within the dijit lifecycle method postMixInProperties, which is inherited

from _Widget. Manipulating

template strings after this point may produce undesirable

intermittent display twitches.

Without further ado, Example 12-3 shows how the dijit's JavaScript file should appear if we want to manipulate the properties in the template to display a custom greeting.

Example 12-3. HelloWorld (Take 2: postMixInProperties)

//An example of properly manipulating a dijit property referenced

//in a template string via postMixInProperties

dojo.provide("dtdg.HelloWorld");

dojo.require("dijit._Widget");

dojo.require("dijit._Templated");

dojo.declare(

"dtdg.HelloWorld",

[dijit._Widget, dijit._Templated],

{

greeting : "",

templatePath: dojo.moduleUrl(

"dtdg",

"templates/HelloWorld.html"

),

postMixInProperties: function( ) {

//Proper manipulation of properties referenced in templates.

this.greeting = "Hello World"; //supply as static greeting.

}

}

);As alluded to earlier, you can save a synchronous call back to the server by specifying the template string directly inside of your JavaScript file. The next variation on the HelloWorld in Example 12-4 demonstrates just how easy this is to do manually, but keep in mind that the Dojo build scripts found in Util can automate this process for all of your dijits as part of a deployment routine.

Example 12-4. HelloWorld (Take 3: templateString)

dojo.provide("dtdg.HelloWorld");

dojo.require("dijit._Widget");

dojo.require("dijit._Templated");

dojo.declare(

"dtdg.HelloWorld",

[dijit._Widget, dijit._Templated],

{

greeting : "",

//Provide the template string inline like so...

templateString : "<div class='hello_class'>${greeting}</div>",

postMixInProperties: function( ) {

console.log ("postMixInProperties");

//We can still manipulate the template string like usual

this.greeting = "Hello World";

}

}

);In this example, templateString provides the template

inline, so there's no need for a separate template file. This, in

turn, saves a synchronous call to the server. If you can imagine

lots of dijits with lots of template strings, it's pretty obvious

that baking the template strings into the dijit's JavaScript files

can significantly reduce the time it takes to load a page. For

production situations, you won't want to do without the Util's build

system (Chapter 16) to automate

these kinds of performance optimizations for you.

As yet another improvement to our HelloWorld dijit, let's

learn how to pass in custom parameters to dijits through the

template. Given the previous example, let's suppose that we want to

supply the custom greeting that is to appear in our widget from its

markup that appears alongside the dojoType tag. Easy; just pass it in like

so:

<div dojoType="dtdg.HelloWorld" greeting="Hello World"

></div>Passing in the parameter for a widget that is programmatically created is just as simple:

var hw = new dtdg.HelloWorld({greeting : "Hello World"

}, theWidgetsDomNode);Of course, you are not limited to passing in values that are

reflected in the template. You can pass in other parameters that are

used in other ways as well. Consider the following DIV element containing a reference to your

HelloWorld dijit that specifies two extra key/value pairs:

<div foo="bar" baz="quux" dojoType="dtdg.HelloWorld"></div>

Wouldn't it be handy to be able to pass in custom data to dijits like that so that they can use it for initialization purposes—allowing application-level developers to not even have to so much as even peek at the source code and only hack on the template a bit? Well, ladies and gentlemen, you can, and the JavaScript file in Example 12-5 illustrates just how to do it.

Example 12-5. HelloWorld (Take 4: custom parameters)

dojo.provide("dtdg.HelloWorld");

dojo.require("dijit._Widget");

dojo.require("dijit._Templated");

dojo.declare(

"dtdg.HelloWorld",

[dijit._Widget, dijit._Templated],

{

templateString : "<div class='hello_class'>Hello World</div>",

foo : "",

//you can't set dijit properties that don't exist

//baz : "",

//tags specified in the element that supplies the dojoType tag

//are passed into the constructor only if they're defined as

//a dijit property a priori. Thus, the baz="quux" has no effect

//in this example because the dijit has no property named baz

constructor: function( ) {

console.log("constructor: foo=" , this.foo);

console.log("constructor: baz=" , this.baz);

}

}

);As you might have noticed, there's an emphasis on making the

point that you can only pass in values for dijit

properties that exist ; you cannot create new dijit

properties by tossing in whatever you feel like into the element

that contains the dojoType

placeholder tag. If you run the previous code example and examine

the Firebug console, you'll see the following console output:

constructor: foo=bar constructor: baz=undefined

While passing in string values to dijits is useful, string values alone are of limited utility because life is usually just not that simple—but not to worry: Dojo allows you to pass in lists and associative arrays to dijits as well. All that is required is that you define dijit properties as the appropriate type in the JavaScript file, and Dojo takes care of the rest.

The following example illustrates how to pass lists and associative arrays into the dijit through the template.

Including the parameters in the element containing the

dojoType tag is

straightforward:

<div

foo="[0,20,40]"

bar="[60,80,100]"

baz="{'a':'b', 'c':'d'}"

dojoType="dtdg.HelloWorld"

></div>And the JavaScript file is just as predictable:

dojo.provide("dtdg.HelloWorld");

dojo.require("dijit._Widget");

dojo.require("dijit._Templated");

dojo.declare(

"dtdg.HelloWorld",

[dijit._Widget, dijit._Templated],

{

templateString : "<div class='hello_class'>Hello World</div>",

foo : [], //cast the value as an array

bar : "", //cast the value as a String

baz : {}, //cast the value as an object

postMixInProperties: function( ) {

console.log("postMixInProperties: foo[1]=" , this.foo[1]);

console.log("postMixInProperties: bar[1]=" , this.bar[1]);

console.log("postMixInProperties: baz['a']=", this.baz['a']);

}

}

);Here's the output in the Firebug console:

postMixInProperties: foo[1]=20 postMixInProperties: bar[1]=6 postMixInProperties: baz['a']=b

Note that even though the value associated with the dijit's

property bar

appears to be a list in the page that includes

the template, it is defined as a string value in the JavaScript

file. Thus, Dojo treats it as a string, and it gets sliced as a

string. In general, the parser tries to interpret values into the

corresponding types by introspecting them via duck typing.

Warning

Take extra-special care not to incorrectly define parameter types in the JavaScript file or it may cost you some debugging time!

As yet another variation on our HelloWorld dijit, consider the

utility in associating a DOM event such as a mouse click or mouse

hover with the dijit. Dojo makes associating events with dijits

easy. You simply specify key/value pairs of the form DOMEvent: dijitMethod inside of a dojoAttachEvent tag that appears as a part

of your template. You may specify multiple key/value pairs or more

than one kind of native DOM event by separating them with a

comma.

Let's illustrate how to use dojoAttachEvent by applying a particular

style that's defined as a class in a stylesheet whenever a mouseover event occurs and remove the

style whenever a mouseout event

occurs. Because DIV elements span

the width of the frame, we'll modify it to be an inline SPAN, so that the mouse event is triggered

only when the cursor is directly over the text. Let's apply the

pointer style to the

cursor.

The changes to the style are simple. We change the reference

to an inline SPAN instead of a

DIV and change the mouse cursor

to a pointer:

span.hello_class {

cursor: pointer;

color: #009900;

}The JavaScript file in Example 12-6 includes the updated

template string, illustrating that the use of dojoAttachEvent is fairly straightforward

as well.

Example 12-6. HelloWorld (Take 5: dojoAttachEvent)

dojo.provide("dtdg.HelloWorld");

dojo.require("dijit._Widget");

dojo.require("dijit._Templated");

dojo.declare(

"dtdg.HelloWorld",

[dijit._Widget, dijit._Templated],

{

templateString :

"<span class='hello_class' dojoAttachEvent='onmouseover:onMouseOver,

onmouseout:

onMouseOut'>Hello World</span>",

onMouseOver : function(evt) {

dojo.addClass(this.domNode, 'hello_class');

console.log("applied hello_class...");

console.log(evt);

},

onMouseOut : function(evt) {

dojo.removeClass(this.domNode, 'hello_class');

console.log("removed hello_class...");

console.log(evt);

}

}

);See how easy that was? When you trigger an onmouseover event over the text in the

SPAN element, style is applied

with the dojo.addClass function,

which is defined in Base. Then, when you trigger an onmouseout event, the style is removed.

Neat stuff!

Did you also notice that the event handling methods included

an evt parameter that passes in

highly relevant event information? As you might have guessed,

internally, dojo.connect is at

work standardizing the event object for you. Here's the Firebug

output that appears when you run the code, which also illustrates

the event information that gets passed into your dijit's event

handlers:

applied hello_class... mouseover clientX=64, clientY=11 removed hello_class clientX=65, clientY=16 mouseover clientX=65, clientY=16

Warning

Take care not to misspell the names of native DOM events,

and ensure that native DOM event names stay in all lowercase. For

example, using ONMOUSEOVER or

onMouseOver won't work for the

onmouseover DOM event, and

unfortunately, Firebug can't give you any indication that anything

is wrong. Because you can name your dijit event handling methods

whatever you want (with whatever capitalization you want), this

can sometimes be easy to forget.

To be perfectly clear, note that the previous example's

mapping of onmouseover to

onMouseOver and onmouseout to onMouseOut is purely a simple convention,

although it does make good sense and results in highly readable

code. Also, it is important to note that events such as onmouseover and onmouseout are DOM

events, while onMouseOver and onMouseOut are methods

associated with a particular dijit. The distinction may

not immediately be clear because the naming reads the same, but it

is an important concept that you'll need to internalize during your

quest for Dijit mastery. The semantics between the two are similar

and different in various respects.

Get Dojo: The Definitive Guide now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.