Chapter 4. Processing Architecture

And now for something completely different.

The previous chapter presented the core ASP.NET Web API programming model, introducing the set of fundamental concepts, interfaces, and classes exposed by this framework. Before we address the book’s core subject of designing evolvable Web APIs, this chapter takes a short detour to look under the hood and present the underlying ASP.NET Web API processing architecture, detailing what happens between the reception of an HTTP request and the return of the corresponding HTTP response message. It also serves as a road map for the more advanced ASP.NET Web API features that we will be addressing in the third part of this book.

During this chapter we will be using the HTTP request presented in Example 4-1, associated with the controller defined in Example 4-2, as a concrete example to illustrate the runtime behavior of this architecture.

The ProcessesController contains a Get action that returns a representation of all the machine’s processes with a given image name.

The exemplifying HTTP request is a GET on the resource identified by http://localhost:50650/api/processes?name=explorer, which represents all the explorer processes currently executing.

GET http://localhost:50650/api/processes?name=explorer HTTP/1.1 User-Agent: Fiddler Host: localhost:50650 Accept: application/json

publicclassProcessesController:ApiController{publicProcessCollectionStateGet(stringname){if(string.IsNullOrEmpty(name)){thrownewHttpResponseException(HttpStatusCode.NotFound);}returnnewProcessCollectionState{Processes=Process.GetProcessesByName(name).Select(p=>newProcessState(p))};}}publicclassProcessState{publicintId{get;set;}publicstringName{get;set;}publicdoubleTotalProcessorTimeInMillis{get;set;}...publicProcessState(){}publicProcessState(Processproc){Id=proc.Id;Name=proc.ProcessName;TotalProcessorTimeInMillis=proc.TotalProcessorTime.TotalMilliseconds;...}}publicclassProcessCollectionState{publicIEnumerable<ProcessState>Processes{get;set;}}

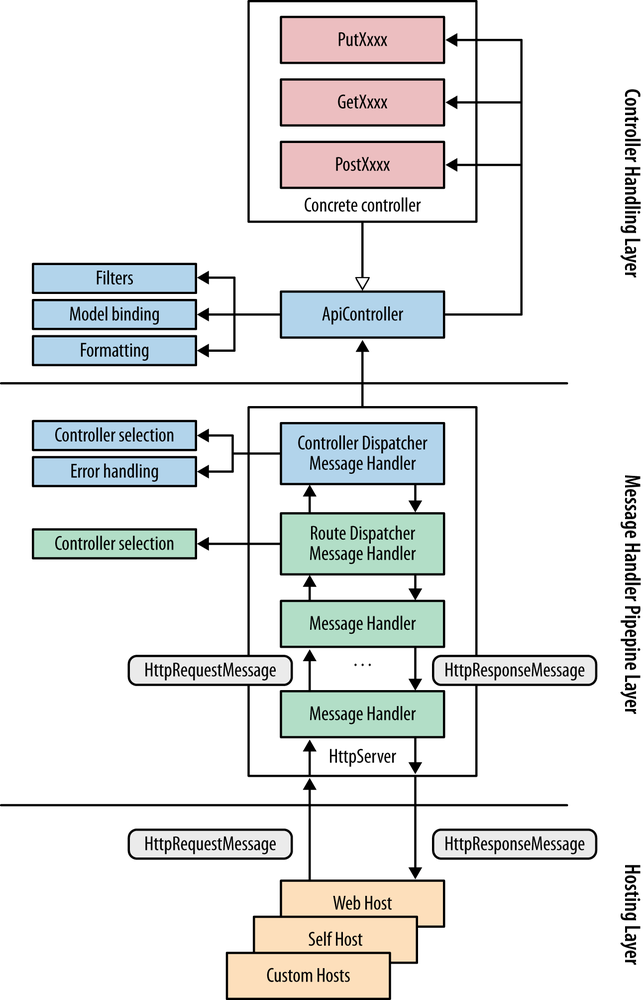

The ASP.NET web processing architecture, represented in Figure 4-1, is composed of three layers:

- The hosting layer is the interface between Web API and the underlying HTTP stacks.

- The message handler pipeline layer can be used for implementing cross-cutting concerns such as logging and caching. However, the introduction of OWIN (discussed in Chapter 11) moves some of these responsibilties down the stack into OWIN middleware.

- The controller handling layer is where controllers and actions are called, parameters are bound and validated, and the HTTP response message is created. Additionally, this layer contains and executes a filter pipeline.

Let’s delve a bit deeper into each layer.

The Hosting Layer

The bottom layer in the Web API processing architecture is responsible for the hosting and acts as the interface between Web API and an underlying HTTP infrastructure, such as the classic ASP.NET pipeline, the HttpListener class found in the .NET Framework’s System.Net assembly, or an OWIN host.

The hosting layer is responsible for creating HttpRequestMessage instances, representing HTTP requests, and then pushing them into the upper message handler pipeline.

As part of processing a response, the hosting layer is also responsible for taking an HttpResponseMessage instance returned from the message handler pipeline and transforming it into a response that can be processed by the underlying network stack.

Remember that HttpRequestMessage and HttpResponseMessage are the new classes for representing HTTP messages, introduced in version 4.5 of the .NET Framework.

The Web API processing architecture is built around these new classes, and the primary task of the hosting layer is to bridge them and the native message representations used by the underlying HTTP stacks.

At the time of writing, ASP.NET Web API includes several hosting layer alternatives, namely:

- Self-hosting in any Windows process (e.g., console application or Windows service)

- Web hosting (using the ASP.NET pipeline on top of Internet Information Services (IIS))

- OWIN hosting (using an OWIN-compliant server, such as Katana)[2]

The first hosting alternative is implemented on top of WCF’s self-hosting capabilities and will be described in Chapter 10 in greater detail.

The second alternative—web hosting—uses the ASP.NET pipeline and its routing capabilities to forward HTTP requests to a new ASP.NET handler, HttpControllerHandler.

This handler bridges the classical ASP.NET pipeline and the new ASP.NET Web API architecture by translating the incoming HttpRequest instances into HttpRequestMessage instances and then pushing them into the Web API pipeline.

This handler is also responsible for taking the returned HttpResponseMessage instance and copying it into the HttpResponse instance before returning to the underlying ASP.NET pipeline.

Finally, the third hosting option layers Web API on top of an OWIN-compliant server.

In this case, the hosting layer translates from the OWIN context objects into a new HttpRequestMessage object sent to Web API.

Inversely, it takes the HttpResponseMessage returned by Web API and writes it into the OWIN context.

There is a fourth option, which removes the hosting layer entirely: requests are sent directly by HttpClient, which uses the same class model, into the Web API runtime without any adaptation.

Chapter 11 presents a deeper exploration of the hosting layer.

Message Handler Pipeline

The middle layer of the processing architecture is the message handler pipeline. This layer provides an extensibility point for interceptors that addresses cross-cutting concerns such as logging and caching. It is similar in purpose to the middleware concept found in Ruby’s Rack, Python’s WSGI (Web Server Gateway Interface), and the Node.js Connect framework.

A message handler is simply an abstraction for an operation that receives an HTTP request message (HttpRequestMessage instance) and returns an HTTP response message (HttpResponseMessage instance).

The ASP.NET Web API message handler pipeline is a composition of these handlers, where each one (except the last) has a reference to the next, called the inner handler.

This pipeline organization provides a great deal of flexibility in the type of operations that can be performed, as depicted in Figure 4-2.

The diagram on the left illustrates the usage of a handler to perform some pre- and postprocessing over request and response messages, respectively.

Processing flows from handler to handler via the InnerHandler relationship—in one direction for request processing and in the reverse direction for response processing.

Examples of pre- and postprocessing are:

-

Changing the request HTTP method, based on the presence of a header such as

X-HTTP-Method-Override, before it arrives to the controller’s action -

Adding a response header such as

Server - Capturing and logging diagnostic or business metric data

You can use handlers to short-circuit the pipeline by directly producing an HTTP response, as shown on the right side of Figure 4-2.

A typical use case for this behavior is the immediate return of an HTTP response with a 401 (Unauthorized) status if the request isn’t properly authenticated.

In the .NET Framework, message handlers are classes that derive from the new HttpMessageHandler abstract class, as shown in Figure 4-3.

The abstract SendAsync method receives an HttpRequestMessage and asynchronously produces an HttpResponseMessage by returning Task<HttpResponseMessage>.

This method also receives a CancellationToken, following the TAP (Task Asynchronous Pattern) guidelines for cancellable operations.

The message handler pipeline organization just described requires a data member to hold a reference to an inner handler as well as data flow logic to delegate requests and response messages from a handler to its inner handler.

These additions are implemented by the DelegatingHandler class, which defines the InnerHandler property to connect a handler with its inner handler.

The sequence of delegating message handlers that constitute the pipeline is defined in ASP.NET Web API’s configuration object model on the HttpConfiguration.MessageHandlers collection property

(e.g., config.MessageHandlers.Add(new TraceMessageHandler());).

The message handlers are ordered in the pipeline according to the config.MessageHandlers collection order.

ASP.NET Web API 2.0 introduces support for the OWIN model, providing the OWIN middleware as an alternative to message handlers as a way to implement cross-cutting concerns. The main advantage of OWIN middleware is that it can be used with other web frameworks (e.g., ASP.NET MVC or SignalR), since it isn’t tied specifically to Web API. As an example, the new security features introduced in Web API 2.0 and presented in Chapter 15 are mostly implemented as OWIN middleware and reusable outside of Web API. On the other hand, message handlers have the advantage of also being usable on the client side, as described in Chapter 14.

Route Dispatching

At the end of the message handler pipeline, there are always two special handlers:

The routing dispatcher handler performs the following:

-

Obtains the routing data from the message (e.g., when web hosting is used) or performs the route resolution if it wasn’t performed previously (e.g., when self-hosting is used). If no route was matched, it produces a response message with the

404 Not FoundHTTP status code. -

Uses the route data to select the next handler to which to forward the request, based on the matched

IHttpRoute.

The controller dispatcher handler is responsible for:

-

Using the route data and a controller selector to obtain a controller description. If no controller description is found, a response message with the

404 Not Foundstatus code is returned. -

Obtaining the controller instance and calling its

ExecuteAsyncmethod, passing the request message. -

Handling exceptions returned by the controller and converting them into response messages with a

500 Internal Errorstatus code.

For instance, using the HTTP request of Example 4-1 and the default route configuration, the route data will contain only one entry with the controller key and processes value.

This single route data entry is the result of matching the http://localhost:50650/api/processes?name=explorer request URI with the /api/{controller}/{id} route template.

By default, the routing dispatcher forwards the request message to the controller dispatcher, which then calls the controller. However, it is possible to explicitly define a per-route handler, as shown in Figure 4-4.

In this case, the request is forwarded to the handler defined by the route, not to the default controller dispatcher. Reasons for using per-route dispatching include flowing the request message through a route-specific handler pipeline. A concrete example is the use of distinct authentication methods, implemented in message handlers, for different routes. Another reason for using per-route dispatching is the substitution of an alternative framework for the Web API top layer (controller handling).

Controller Handling

The final and uppermost layer in the processing architecture is the controller handling. This layer is responsible for receiving a request message from the underlying pipeline and transforming it into a call to a controller’s action method, passing the required method parameters. It also is responsibile for converting the method’s return value into a response message and passing it back to the message handler pipeline.

Bridging the message handler pipeline and the controller handling is performed by the controller dispatcher, which is still a message handler. Its main task is to select, create, and call the correct controller to handle a request. This process is detailed in Chapter 12, which presents all the relevant classes and shows how you can change the default behavior using the available extensibility points.

The ApiController Base Class

The concrete controller that ultimately handles the request can directly implement the IHttpController interface.

However, the common scenario, as presented in the previous chapter, is for the concrete controller to derive from the abstract ApiController class, as shown in Figure 4-5.

It is the job of ApiController.ExecuteAsync to select the appropriate action, given the HTTP request method (e.g., GET or POST), and call the associated method on the derived concrete controller.

For instance, the GET request in Example 4-1 will be dispatched to the ProcessesController.Get(string name) method.

After the action is selected but before the method is invoked, the ApiController class executes a filter pipeline, as shown in Figure 4-6.

Each action has its own pipeline composed of the following functionalities:

- Parameter binding

-

Conversion from the action’s return into an

HttpResponseMessage - Authentication, authorization, and action filters

- Exception filters

Parameter binding

Parameter binding is the computation of the action’s parameter values, used when calling the action’s method. This process is illustrated in Figure 4-7 and uses information from several sources, namely:

- The route data (e.g., route parameters)

- The request URI query string

- The request body

- The request headers

When executing the action’s pipeline, the ApiController.ExecuteAsync method calls a sequence of HttpParameterBinding instances, where each one is associated with one of the action’s method parameters.

Each HttpParameterBinding instance computes the value of one parameter and adds it to the ActionArguments dictionary in the HttpActionContext instance.

HttpParameterBinding is an abstract class with multiple derived concrete classes, one for each type of parameter binding.

For instance, the FormatterParameterBinding class uses the request body content and a formatter to obtain the parameter value.

Formatters are classes that extend the abstract MediaTypeFormatter class and perform bidirectional conversions between CLR (Common Language Runtime) types and byte stream representations, as defined by Internet media types. Figure 4-8 illustrates the functionality of these formatters.

A different kind of parameter binding is the ModelBinderParameterBinding class, which instead uses the concept of model binders to fetch information from the route data, in a manner similar to ASP.NET MVC.

For instance, consider the action in Example 4-2 and the HTTP request in Example 4-1: the name parameter in the GET method will be bound to the value explorer—that is, the value for the query string entry with name key.

We’ll provide more detail on formatters, model binding, and validation in Chapter 13.

Conversion into an HttpResponseMessage

After the action method ends and before the result is returned to the filter pipeline, the action result, which can be any object, must be converted into an HttpResponseMessage.

If the return type is assignable to the IHttpActionResult interface[3] (presented in Example 4-3), then the result’s ExecuteAsync method is called to convert it into a response message.

There are several implementations of this interface, such as OkResult and RedirectResult, that can be used in the action’s code.

The ApiController base class also includes several protected methods (not shown in Figure 4-5) that can be used by derived classes to construct IHttpActionResult implementations (e.g., protected internal virtual OkResult Ok()).

publicinterfaceIHttpActionResult{Task<HttpResponseMessage>ExecuteAsync(CancellationTokencancellationToken);}

If the return isn’t a IHttpActionResult, then an external result converter, implementing the IActionResultConverter interface as defined in Example 4-4, is selected and used to produce the response message.

publicinterfaceIActionResultConverter{HttpResponseMessageConvert(HttpControllerContextcontrollerContext,objectactionResult);}

For the HTTP request in Example 4-1, the selected result converter will try to locate a formatter that can read a ProcessCollectionState (i.e., the type returned by the action’s method), and produce a byte stream representation of it in application/json (i.e., the value of the request’s Accept header).

In the end, the resulting response is the one presented in Example 4-5.

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Cache-Control: no-cache

Pragma: no-cache

Content-Type: application/json; charset=utf-8

Expires: -1

Server: Microsoft-IIS/8.0

Date: Thu, 25 Apr 2013 11:50:12 GMT

Content-Length: (...)

{"Processes":[{"Id":2824,"Name":"explorer",

"TotalProcessorTimeInMillis":831656.9311}]}Formatters and content negotiation are addressed in more detail in Chapter 13.

Filters

Authentication, authorizations, and action filters are defined by the interfaces listed in Example 4-6, and have a role similar to message handlers—namely, to implement cross-cutting concerns (e.g., authentication, authorization, and validation).

publicinterfaceIFilter{boolAllowMultiple{get;}}publicinterfaceIAuthenticationFilter:IFilter{TaskAuthenticateAsync(HttpAuthenticationContextcontext,CancellationTokencancellationToken);TaskChallengeAsync(HttpAuthenticationChallengeContextcontext,CancellationTokencancellationToken);}publicinterfaceIAuthorizationFilter:IFilter{Task<HttpResponseMessage>ExecuteAuthorizationFilterAsync(HttpActionContextactionContext,CancellationTokencancellationToken,Func<Task<HttpResponseMessage>>continuation);}publicinterfaceIActionFilter:IFilter{Task<HttpResponseMessage>ExecuteActionFilterAsync(HttpActionContextactionContext,CancellationTokencancellationToken,Func<Task<HttpResponseMessage>>continuation);}publicinterfaceIExceptionFilter:IFilter{TaskExecuteExceptionFilterAsync(HttpActionExecutedContextactionExecutedContext,CancellationTokencancellationToken);}

For authorization and action filters, the pipeline is organized similarly to the message handler pipeline: each filter receives a reference to the next one in the pipeline and has the ability to perform pre- and postprocessing over the request and the response. Alternatively, the filter can produce a new response and end the request immediately, thereby short-circuiting any further processing (namely, the action’s invocation). Authentication filters operate under a slightly different model, as we will see in Chapter 15.

The main difference between authorization and action filters is that the former are located before parameter binding takes place, whereas the latter are located after this binding.

As a result, authorization filters are an adequate extension point to insert operations that should be performed as early in the pipeline as possible.

The typical example is verifying if the request is authorized and immediately producing a 401 (Not authorized) HTTP response message if it is not.

On the other hand, action filters are appropriate when access to the bound parameters is required.

A fourth filter type, exception filters, is used only if the Task<HttpResponseMessage> returned by the filter pipeline is in the faulted state; that is, there was an exception.

Each exception filter is called in sequence and has the chance to handle the exception by creating an HttpResponseMessage.

Recall that if the controller dispatcher handler receives an unhandled exception, an HTTP response message with a status code of 500 (Internal Server Error) is returned.

We can associate filters to controllers or actions in multiple ways:

- Via attributes, similarly to what is supported by ASP.NET MVC

-

By explicitly registering filter instances in the configuration object, using the

HttpConfiguration.Filterscollection -

By registering

IFilterProviderimplementation in the configuration service’s container

After the HttpResponseMessage instance has left the action pipeline, it is returned by ApiController to the controller dispatcher handler.

Then it descends through the message handler pipeline until it is converted into a native HTTP response by the hosting layer.

Conclusion

This chapter concludes the first part of the book, the aim of which was to introduce ASP.NET Web API, the motivation behind its existence, its basic programming model, and its core processing architecture. Using this knowledge, we will shift focus in the next part to the design, implementation, and consumption of evolvable Web APIs, using ASP.NET Web API as the supporting platform.

Get Designing Evolvable Web APIs with ASP.NET now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.