Each machine has its own, unique personality which probably could be defined as the intuitive sum total of everything you know and feel about it. This personality constantly changes, usually for the worse, but sometimes surprisingly for the better...

âRobert M. Pirsig, Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

This book is about designing and building specialized computers. We all know what a computer is. It's that box that sits on your desk, quietly purring away (or rattling if the fan is shot), running your programs and regularly crashing (if you're not running some variety of Unix). Inside that box is the electronics that runs your software, stores your information, and connects you to the world. It's all about processing information. Designing a computer, therefore, is about designing a machine that holds and manipulates data.

Computer systems fall into essentially two separate categories. The first, and most obvious, is that of the desktop computer. When you say "computer" to someone, this is the machine that usually comes to her mind. The second type of computer is the embedded computer, a computer that is integrated into another system for the purposes of control and/or monitoring. Embedded computers are far more numerous than desktop systems, but far less obvious. Ask the average person how many computers he has in his home, and he might reply that he has one or two. In fact, he may have 30 or more, hidden inside his TVs, VCRs, DVD players, remote controls, washing machines, cell phones, air conditioners, game consoles, ovens, toys, and a host of other devices.

In this chapter, we'll look at computer architecture in general. This is applicable to both embedded and desktop computers, because the primary difference between an embedded machine and a general-purpose computer is its application. The basic principles of operation and the underlying architectures are fundamentally the same.

Both have a processor, memory, and often several forms of input and output. The primary difference lies in their intended use, and this is reflected in the system design and their software. Desktop computers can run a variety of application programs, with system resources orchestrated by an operating system. By running different application programs, the functionality of the desktop computer is changed. One moment, it may be used as a word processor; the next it is an MP3 player or a database client. Which software is loaded and run is under user control.

In contrast, the embedded computer is normally dedicated to a specific task. In many cases, an embedded system is used to replace application-specific electronics. The advantage of using an embedded microprocessor over dedicated electronics is that the functionality of the system is determined by the software, not the hardware. This makes the embedded system easier to produce, and much easier to evolve, than a complicated circuit.

The embedded system typically has one application and one application only, which is permanently running. The embedded computer may or may not have an operating system, and rarely does it provide the user with the ability to arbitrarily install new software. The software is normally contained in the system's nonvolatile memory, unlike a desktop computer where the nonvolatile memory contains boot software and (maybe) low-level drivers only.

Embedded hardware is often much simpler than a desktop system, but it can also be far more complex too. An embedded computer may be implemented in a single chip with just a few support components, and its purpose may be as crude as a controller for a garden-watering system. Alternatively, the embedded computer may be a 150-processor, distributed parallel machine responsible for all the flight and control systems of a commercial jet. As diverse as embedded hardware may be, the underlying principles of design are the same.

This chapter introduces some important concepts relating to computer architecture, with specific emphasis on those topics relevant to embedded systems. Its purpose is to give you grounding before moving on to the more hands-on information that begins in Chapter 2. In this chapter, you'll learn about the basics of processors, interrupts, the difference between RISC and CISC, parallel systems, memory, and I/O.

In essence, a computer is a machine designed to process, store, and retrieve data. Data may be numbers in a spreadsheet, characters of text in a document, dots of color in an image, waveforms of sound, or the state of some system, such as an air conditioner or a CD player. All data is stored in the computer as numbers. It's easy to forget this when we're deep in C code, contemplating complex algorithms and data structures.

The computer manipulates the data by performing operations on the numbers. Displaying an image on a screen is accomplished by moving an array of numbers to the video memory, each number representing a pixel of color. To play an MP3 audio file, the computer reads an array of numbers from disk and into memory, manipulates those numbers to convert the compressed audio data into raw audio data, and then outputs the new set of numbers (the raw audio data) to the audio chip.

Everything that a computer does, from web browsing to printing, involves moving and processing numbers. The electronics of a computer is nothing more than a system designed to hold, move, and change numbers.

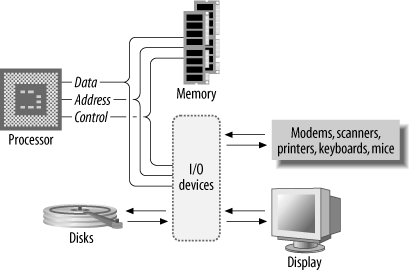

A computer system is composed of many parts, both hardware and software. At the heart of the computer is the processor, the hardware that executes the computer programs. The computer also has memory, often several different types in one system. The memory is used to store programs while the processor is running them, as well as store the data that the programs are manipulating. The computer also has devices for storing data, or exchanging data with the outside world. These may allow the input of text via a keyboard, the display of information on a screen, or the movement of programs and data to or from a disk drive.

The software controls the operation and functionality of the computer. There are many "layers" of software in the computer (Figure 1-1). Typically, a given layer will only interact with the layers immediately above or below it.

At the lowest level, there are programs that are run by the processor when the computer first powers up. These programs initialize the other hardware subsystems to a known state and configure the computer for correct operation. This software, because it is permanently stored in the computer's memory, is known as firmware .

The bootloader is located in the firmware. The bootloader is a special program run by the processor that reads the operating system from disk (or nonvolatile memory or network interface) and places it in memory so that the processor may then run it. The bootloader is present in desktop computers and workstations, and may be present in some embedded computers.

Above the firmware, the operating system controls the operation of the computer. It organizes the use of memory and controls devices such as the keyboard, mouse, screen, disk drives, and so on. It is also the software that often provides an interface to the user, enabling her to run application programs and access her files on disk. The operating system typically provides a set of software tools for application programs, providing a mechanism by which they too can access the screen, disk drives, and so on. Not all embedded systems use or even need an operating system. Often, an embedded system will simply run code dedicated to its task, and the presence of an operating system is overkill. In other instances, such as network routers, an operating system provides necessary software integration and greatly simplifies the development process. Whether an operating system is needed and useful really depends on the intended purpose of the embedded computer and, to a lesser degree, on the preference of the designer.

At the highest level, the application software constitutes the programs that provide the functionality of the computer. Everything below the application is considered system software . For embedded computers, the boundary between application and system software is often blurred. This reflects the underlying principle in embedded design that a system should be designed to achieve its objective in as simple and straightforward a manner as possible.

The processor is the most important part of a computer, the component around which everything else is centered. In essence, the processor is the computing part of the computer. A processor is an electronic device capable of manipulating data (information) in a way specified by a sequence of instructions. The instructions are also known as opcodes or machine code . This sequence of instructions may be altered to suit the application, and, hence, computers are programmable. A sequence of instructions is what constitutes a program.

Instructions in a computer are numbers, just like data. Different numbers, when read and executed by a processor, cause different things to happen. A good analogy is the mechanism of a music box. A music box has a rotating drum with little bumps, and a row of prongs. As the drum rotates, different prongs in turn are activated by the bumps, and music is produced. In a similar way, the bit patterns of instructions feed into the execution unit of the processor. Different bit patterns activate or deactivate different parts of the processing core. Thus, the bit pattern of a given instruction may activate an addition operation, while another bit pattern may cause a byte to be stored to memory.

A sequence of instructions is a machine-code program. Each type of processor has a different instruction set, meaning that the functionality of the instructions (and the bit patterns that activate them) varies. Processor instructions are often quite simple, such as "add two numbers" or "call this function." In some processors, however, they can be as complex and sophisticated as "if the result of the last operation was zero, then use this particular number to reference another number in memory, and then increment the first number once you've finished." This will be covered in more detail in the section on CISC and RISC processors, later in this chapter.

The processor alone is incapable of successfully performing any tasks. It requires memory (for program and data storage), support logic, and at least one I/O device ("input/output device") used to transfer data between the computer and the outside world. The basic computer system is shown in Figure 1-2.

A microprocessor is a processor implemented (usually) on a single, integrated circuit. With the exception of those found in some large supercomputers, nearly all modern processors are microprocessors, and the two terms are often used interchangeably. Common microprocessors in use today are the Intel Pentium series, Freescale/IBM PowerPC, MIPS, ARM, and the Sun SPARC, among others. A microprocessor is sometimes also known as a CPU (Central Processing Unit).

A microcontroller is a processor, memory, and some I/O devices contained within a single, integrated circuit, and intended for use in embedded systems. The buses that interconnect the processor with its I/O exist within the same integrated circuit. The range of available microcontrollers is very broad. They range from the tiny PICs and AVRs (to be covered in this book) to PowerPC processors with built-in I/O, intended for embedded applications. In this book, we will look at both microprocessors and microcontrollers.

Microcontrollers are very similar to System-on-Chip (SoC) processors, intended for use in conventional computers such as PCs and workstations. SoC processors have a different suite of I/O, reflecting their intended application, and are designed to be interfaced to large banks of external memory. Microcontrollers usually have all their memory on-chip and may provide only limited support for external memory devices.

The memory of the computer system contains both the instructions that the processor will execute and the data it will manipulate. The memory of a computer system is never empty. It always contains something, whether it be instructions, meaningful data, or just the random garbage that appeared in the memory when the system powered up.

Instructions are read (fetched) from memory, while data is both read from and written to memory, as shown in Figure 1-3.

This form of computer architecture is known as a Von Neumann machine, named after John Von Neumann, one of the originators of the concept. With very few exceptions, nearly all modern computers follow this form. Von Neumann computers are what can be termed control-flow computers. The steps taken by the computer are governed by the sequential control of a program. In other words, the computer follows a step-by-step program that governs its operation.

Tip

There are some interesting non-Von Neumann architectures, such as the massively parallel Connection Machine and the nascent efforts at building biological and quantum computers, or neural networks.

A classical Von Neumann machine has several distinguishing characteristics:

- There is no real difference between data and instructions .

A processor can be directed to begin execution at a given point in memory, and it has no way of knowing whether the sequence of numbers beginning at that point is data or instructions. The instruction 0x4143 may also be data (the number 0x4143, or the ASCII characters "A" and "C"). The processor has no way of telling what is data or what is an instruction. If a number is to be executed by the processor, it is an instruction; if it is to be manipulated, it is data.

Because of this lack of distinction, the processor is capable of changing its instructions (treating them as data) under program control. And because the processor has no way of distinguishing between data and instruction, it will blindly execute anything that it is given, whether it is a meaningful sequence of instructions or not.

- Data has no inherent meaning .

There is nothing to distinguish between a number that represents a dot of color in an image and a number that represents a character in a text document. Meaning comes from how these numbers are treated under the execution of a program.

- Data and instructions share the same memory .

This means that sequences of instructions in a program may be treated as data by another program. A compiler creates a program binary by generating a sequence of numbers (instructions) in memory. To the compiler, the compiled program is just data, and it is treated as such. It is a program only when the processor begins execution. Similarly, an operating system loading an application program from disk does so by treating the sequence of instructions of that program as data. The program is loaded to memory just as an image or text file would be, and this is possible due to the shared memory space.

- Memory is a linear (one-dimensional) array of storage locations .

The processor's memory space may contain the operating system, various programs, and their associated data, all within the same linear space.

Each location in the memory space has a unique, sequential address. The address of a memory location is used to specify (and select) that location. The memory space is also known as the address space , and how that address space is partitioned between different memory and I/O devices is known as the memory map . The address space is the array of all addressable memory locations. In an 8-bit processor (such as the 68HC11) with a 16-bit address bus, this works out to be 216 = 65,536 = 64K of memory. Hence, the processor is said to have a 64K address space. Processors with 32-bit address buses can access 232 = 4,294,967,296 = 4G of memory.

Some processors, notably the Intel x86 family, have a separate address space for I/O devices with separate instructions for accessing this space. This is known as ported I/O . However, most processors make no distinction between memory devices and I/O devices within the address space. I/O devices exist within the same linear space as memory devices, and the same instructions are used to access each. This is known as memory-mapped I/O (Figure 1-4). Memory-mapped I/O is certainly the most common form. Ported I/O address spaces are becoming rare, and the use of the term even rarer.

Most microprocessors available are standard Von Neumann machines. The main deviation from this is the Harvard architecture , in which instructions and data have different memory spaces (Figure 1-5) with separate address, data, and control buses for each memory space. This has a number of advantages in that instruction and data fetches can occur concurrently, and the size of an instruction is not set by the size of the standard data unit (word).

A bus is a physical group of signal lines that have a related function. Buses allow for the transfer of electrical signals between different parts of the computer system and thereby transfer information from one device to another. For example, the data bus is the group of signal lines that carry data between the processor and the various subsystems that comprise the computer. The "width" of a bus is the number of signal lines dedicated to transferring information. For example, an 8-bit-wide bus transfers 8 bits of data in parallel.

The majority of microprocessors available today (with some exceptions) use the three-bus system architecture (Figure 1-6). The three buses are the address bus , the data bus, and the control bus .

The data bus is bidirectional, the direction of transfer being determined by the processor. The address bus carries the address, which points to the location in memory that the processor is attempting to access. It is the job of external circuitry to determine in which external device a given memory location exists and to activate that device. This is known as address decoding . The control bus carries information from the processor about the state of the current access, such as whether it is a write or a read operation. The control bus can also carry information back to the processor regarding the current access, such as an address error. Different processors have different control lines, but there are some control lines that are common among many processors. The control bus may consist of output signals such as read, write, valid address, etc. A processor usually has several input control lines too, such as reset, one or more interrupt lines, and a clock input.

Tip

A few years ago, I had the opportunity to wander through, in, and around CSIRAC (pronounced "sigh-rack"). This was one of the world's first digital computers, designed and built in Sydney, Australia, in the late 1940s. It was a massive machine, filling a very big room with the type of solid hardware that you can really kick. It was quite an experience looking over the old machine. I remember at one stage walking through the disk controller (it was the size of small room) and looking up at a mass of wires strung overhead. I asked what they were for. "That's the data bus!" came the reply.

CSIRAC is now housed in the museum of the University of Melbourne. You can take an online tour of the machine, and even download a simulator, at http://www.cs.mu.oz.au/csirac.

There are six basic types of access that a processor can perform with external chips. The processor can write data to memory or write data to an I/O device, read data from memory or read data from an I/O device, read instructions from memory, and perform internal manipulation of data within the processor.

In many systems, writing data to memory is functionally identical to writing data to an I/O device. Similarly, reading data from memory constitutes the same external operation as reading data from an I/O device, or reading an instruction from memory. In other words, the processor makes no distinction between memory and I/O.

The internal data storage of the processor is known as its registers . The processor has a limited number of registers, and these are used to hold the current data/operands that the processor is manipulating.

The Arithmetic Logic Unit (ALU) performs the internal arithmetic manipulation of data in the processor. The instructions that are read and executed by the processor control the data flow between the registers and the ALU. The instructions also control the arithmetic operations performed by the ALU via the ALU's control inputs. A symbolic representation of an ALU is shown in Figure 1-7.

Whenever instructed by the processor, the ALU performs an operation (typically one of addition, subtraction, NOT, AND, OR, XOR, shift left/right, or rotate left/right) on one or more values. These values, called operands , are typically obtained from two registers, or from one register and a memory location. The result of the operation is then placed back into a given destination register or memory location. The status outputs indicate any special attributes about the operation, such as whether the result was zero, negative, or if an overflow or carry occurred. Some processors have separate units for multiplication and division, and for bit shifting, providing faster operation and increased throughput.

Each architecture has its own unique ALU features, and this can vary greatly from one processor to another. However, all are just variations on a theme, and all share the common characteristics just described.

Interrupts (also known as traps or exceptions in some processors) are a technique of diverting the processor from the execution of the current program so that it may deal with some event that has occurred. Such an event may be an error from a peripheral, or simply that an I/O device has finished the last task it was given and is now ready for another. An interrupt is generated in your computer every time you type a key or move the mouse. You can think of it as a hardware-generated function call.

Interrupts free the processor from having to continuously check the I/O devices to determine whether they require service. Instead, the processor may continue with other tasks. The I/O devices will notify it when they require attention by asserting one of the processor's interrupt inputs. Interrupts can be of varying priorities in some processors, thereby assigning differing importance to the events that can interrupt the processor. If the processor is servicing a low-priority interrupt, it will pause it in order to service a higher-priority interrupt. However, if the processor is servicing an interrupt and a second, lower-priority interrupt occurs, the processor will ignore that interrupt until it has finished the higher-priority service.

When an interrupt occurs, the usual procedure is for the processor to save its state by pushing its registers and program counter onto the stack. The processor then loads an interrupt vector into the program counter. The interrupt vector is the address at which an interrupt service routine (ISR) lies. Thus, loading the vector into the program counter causes the processor to begin execution of the ISR, performing whatever service the interrupting device required. The last instruction of an ISR is always a Return from Interrupt instruction. This causes the processor to reload its saved state (registers and program counter) from the stack and resume its original program. Interrupts are largely transparent to the original program. This means that the original program is completely "unaware" that the processor was interrupted, save for a lost interval of time.

Processors with shadow registers use these to save their current state, rather than pushing their register bank onto the stack. This saves considerable memory accesses (and therefore time) when processing an interrupt. However, since only one set of shadow registers exists, a processor servicing multiple interrupts must "manually" preserve the state of the registers before servicing the higher interrupt. If it does not, important state information will be lost. Upon returning from an ISR, the contents of the shadow registers are swapped back into the main register array.

There are two ways of telling when an I/O device (such as a serial controller or a disk controller) is ready for the next sequence of data to be transferred. The first is busy waiting or polling , where the processor continuously checks the device's status register until the device is ready. This wastes the processor's time but is the simplest to implement. For some time-critical applications, polling can reduce the time it takes for the processor to respond to a change of state in a peripheral.

A better way is for the device to generate an interrupt to the processor when it is ready for a transfer to take place. Small, simple processors may only have one (or two) interrupt inputs, so several external devices may have to share the interrupt lines of the processor. When an interrupt occurs, the processor must check each device to determine which one generated the interrupt. (This can also be considered a form of polling.) The advantage of interrupt polling over ordinary polling is that the polling occurs only when there is a need to service a device. Polling interrupts is suitable only in systems that have a small number of devices; otherwise, the processor will spend too long trying to determine the source of the interrupt.

The other technique of servicing an interrupt is by using vectored interrupts,[*] by which the interrupting device provides the interrupt vector that the processor is to take. Vectored interrupts reduce considerably the time it takes the processor to determine the source of the interrupt. If an interrupt request can be generated from more than one source, it is therefore necessary to assign priorities (levels) to the different interrupts. This can be done in either hardware or software, depending on the particular application. In this scheme, the processor has numerous interrupt lines, with each interrupt corresponding to a given interrupt vector. So, for example, when an interrupt of priority 7 occurs (interrupt lines corresponding to "7" are asserted), the processor loads vector 7 into its program counter and starts executing the service routine specific to interrupt 7.

Vectored interrupts can be taken one step further. Some processors and devices support the device by actually placing the appropriate vector onto the data bus when they generate an interrupt. This means the system can be even more versatile, so that instead of being limited to one interrupt per peripheral, each device can supply an interrupt vector specific to the event that is causing the interrupt. However, the processor must support this function, and most do not.

Some processors have a feature known as a fast hardware interrupt. With this interrupt, only the program counter is saved. It assumes that the ISR will protect the contents of the registers by manually saving their state as required. Fast interrupts are useful when an I/O device requires a very fast response from a processor and cannot wait for the processor to save all its registers to the stack. A special (and separate) interrupt line is used to generate fast interrupts.

A software interrupt is generated by an instruction. It is the lowest-priority interrupt and is generally used by programs to request a service to be performed by the system software (operating system or firmware).

So why are software interrupts used? Why isn't the appropriate section of code called directly? For that matter, why use an operating system to perform tasks for us at all? It gets back to compatibility. Jumping to a subroutine (calling a function) is jumping to a specific address in memory. A future version of the system software may not locate the subroutines at the same addresses as earlier versions. By using a software interrupt, our program does not need to know where the routines lie. It relies on the entry in the vector table to direct it to the correct location.

There are two major approaches to processor architecture: Complex Instruction Set Computer (CISC, pronounced "Sisk") processors and Reduced Instruction Set Computer (RISC) processors. Classic CISC processors are the Intel x86, Motorola 68xxx, and National Semiconductor 32xxx processors, and, to a lesser degree, the Intel Pentium. Common RISC architectures are the Freescale/IBM PowerPC, the MIPS architecture, Sun's SPARC, the ARM, the Atmel AVR, and the Microchip PIC.

CISC processors have a single processing unit, external memory, and a relatively small register set and many hundreds of different instructions. In many ways, they are just smaller versions of the processing units of mainframe computers from the 1960s.

The tendency in processor design throughout the late 70s and early 80s was toward bigger and more complicated instruction sets. Need to input a string of characters from an I/O port? Well, with CISC (80x86 family), there's a single instruction to do it! The diversity of instructions in a CISC processor can run to well over 1,000 opcodes in some processors, such as the Motorola 68000. This had the advantage of making the job of the assembly-language programmer easier, since you had to write fewer lines of code to get the job done. As memory was slow and expensive, it also made sense to make each instruction do more. This reduced the number of instructions needed to perform a given function, and thereby reduced memory space and the number of memory accesses required to fetch instructions. As memory got cheaper and faster, and compilers became more efficient, the relative advantages of the CISC approach began to diminish. One main disadvantage of CISC is that the processors themselves get increasingly complicated as a consequence of supporting such a large and diverse instruction set. The control and instruction decode units are complex and slow, the silicon is large and hard to produce, and they consume a lot of power and therefore generate a lot of heat. As processors became more advanced, the overheads that CISC imposed on the silicon became oppressive.

A given processor feature when considered alone may increase processor performance but may actually decrease the performance of the total system, if it increases the total complexity of the device. It was found that by streamlining the instruction set to the most commonly used instructions, the processors become simpler and faster. Fewer cycles are required to decode and execute each instruction, and the cycles are shorter. The drawback is that more (simpler) instructions are required to perform a task, but this is more than made up for in the performance boost to the processor. For example, if both cycle time and the number of cycles per instruction are each reduced by a factor of four, while the number of instructions required to perform a task grows by 50%, the execution of the processor is sped up by a factor of eight.

The realization of this led to a rethink of processor design. The result was the RISC architecture, which has led to the development of very high-performance processors. The basic philosophy behind RISC is to move the complexity from the silicon to the language compiler. The hardware is kept as simple and fast as possible.

A given complex instruction can be performed by a sequence of much simpler instructions. For example, many processors have an xor (exclusive OR) instruction for bit manipulation, and they also have a clear instruction to set a given register to zero. However, a register can also be set to zero by xor-ing it with itself. Thus, the separate clear instruction is no longer required. It can be replaced with the already present xor. Further, many processors are able to clear a memory location directly by writing a zero to it. That same function can be implemented by clearing a register and then storing that register to the memory location. The instruction to load a register with a literal number can be replaced with the instruction for clearing a register, followed by an add instruction with the literal number as its operand. Thus, six instructions (xor, clear

reg

, clear

memory

, load

literal

, store, and add) can be replaced with just three (xor, store, and add).

So the following CISC assembly pseudocode:

clear 0x1000 ; clear memory location 0x1000 load r1,#5 ; load register 1 with the value 5

becomes the following RISC pseudocode:

xor r1,r1 ; clear register 1 store r1,0x1000 ; clear memory location 0x1000 add r1,#5 ; load register 1 with the value 5

The resulting code size is bigger, but the reduced complexity of the instruction decode unit can result in faster overall operation. Dozens of such code optimizations exist to give RISC its simplicity.

RISC processors have a number of distinguishing characteristics. They have large register sets (in some architectures numbering over 1,000), thereby reducing the number of times the processor must access main memory. Often-used variables can be left inside the processor, reducing the number of accesses to (slow) external memory. Compilers of high-level languages (such as C) take advantage of this to optimize processor performance.

By having smaller and simpler instruction decode units, RISC processors have fast instruction execution, and this also reduces the size and power consumption of the processing unit. Generally, RISC instructions will take only one or two cycles to execute (this depends greatly on the particular processor). This is in contrast to instructions for a CISC processor, whose instructions may take many tens of cycles to execute. For example, one instruction (integer multiplication) on an 80486 CISC processor takes 42 cycles to complete. The same instruction on a RISC processor may take just one cycle. Instructions on a RISC processor have a simple format. All instructions are generally the same length (which makes instruction decode units simpler).

RISC processors implement what is known as a "load/store" architecture. This means that the only instructions that actually reference memory are load and store. In contrast, many (most) instructions on a CISC processor may access or manipulate memory. On a RISC processor, all other instructions (aside from load and store) work on the registers only. This facilitates the ability of RISC processors to complete (most of) their instructions in a single cycle. Consequently, RISC processors do not have the range of addressing modes that are found on CISC processors.

RISC processors also often have pipelined instruction execution. This means that while one instruction is being executed, the next instruction in the sequence is being decoded, while the third one is being fetched. At any given moment, several instructions will be in the pipeline and in the process of being executed. Again, this provides improved processor performance. Thus, even though not all instructions may be completed in a single cycle, the processor may issue and retire instructions on each cycle, thereby achieving effective single-cycle execution. Some RISC processors have overlapped instruction execution, in which load operations may allow the execution of subsequent, unrelated instructions to continue before the data requested by the load has been returned from memory. This allows these instructions to overlap the load, thereby improving processor performance.

Due to their low power consumption and computing power, RISC processors are becoming widely used, particularly in embedded computer systems, and many RISC attributes are appearing in what are traditionally CISC architectures (such as with the Intel Pentium). Ironically, many RISC architectures are adding some CISC-like features, and so the distinction between RISC and CISC is blurring.

An excellent discussion of RISC architectures and processor performance topics can be found in Kevin Dowd and Charles Severance's High Performance Computing (O'Reilly).

So, which is better for embedded and industrial applications, RISC or CISC? If power consumption needs to be low, then RISC is probably the better architecture to use. However, if the available space for program storage is small, then a CISC processor may be a better alternative, since CISC instructions get more "bang" for the byte.

A special type of processor architecture is that of the Digital Signal Processor ( DSP ). These processors have instruction sets and architectures optimized for numerical processing of array data. They often extend the Harvard architecture concept further by not only having separate data and code spaces, but also by splitting the data spaces into two or more banks. This allows concurrent instruction fetch and data accesses for multiple operands. As such, DSPs can have very high throughput and can outperform both CISC and RISC processors in certain applications.

DSPs have special hardware well suited to numerical processing of arrays. They often have hardware looping , whereby special registers allow for and control the repeated execution of an instruction sequence. This is also often known as zero-overhead looping , since no conditions need to be explicitly tested by the software as part of the looping process. DSPs often have dedicated hardware for increasing the speed of arithmetic operations. High-speed multipliers, Multiply-And-Accumulate (MAC) units, and barrel shifters are common features.

DSP processors are commonly used in embedded applications, and many conventional embedded microcontrollers include some DSP functionality.

Get Designing Embedded Hardware, 2nd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.