Tim O’Reilly, November 14, 2022

This document contains an unscientific but illustrative set of examples showing how for highly commercial searches, advertising crowds out organic search results, with implications for “who gets what and why” in the market to which Google has become the gatekeeper. The search terms chosen were just “off the top of my head,” albeit with the filter that the search term might show commercial intent. The points emphasized in the narrative were not sought out a-priori, but are simply observations on the pages that Google served up.

These examples are based on a full-screen window on a Macbook Air laptop screen, with magnification reduced to 67% of normal to fit more content in. They would obviously differ on mobile or on a larger desktop screen, or on a laptop screen at the normal size. Screenshots were taken on November 13 and 14, 2022 from a computer in California.

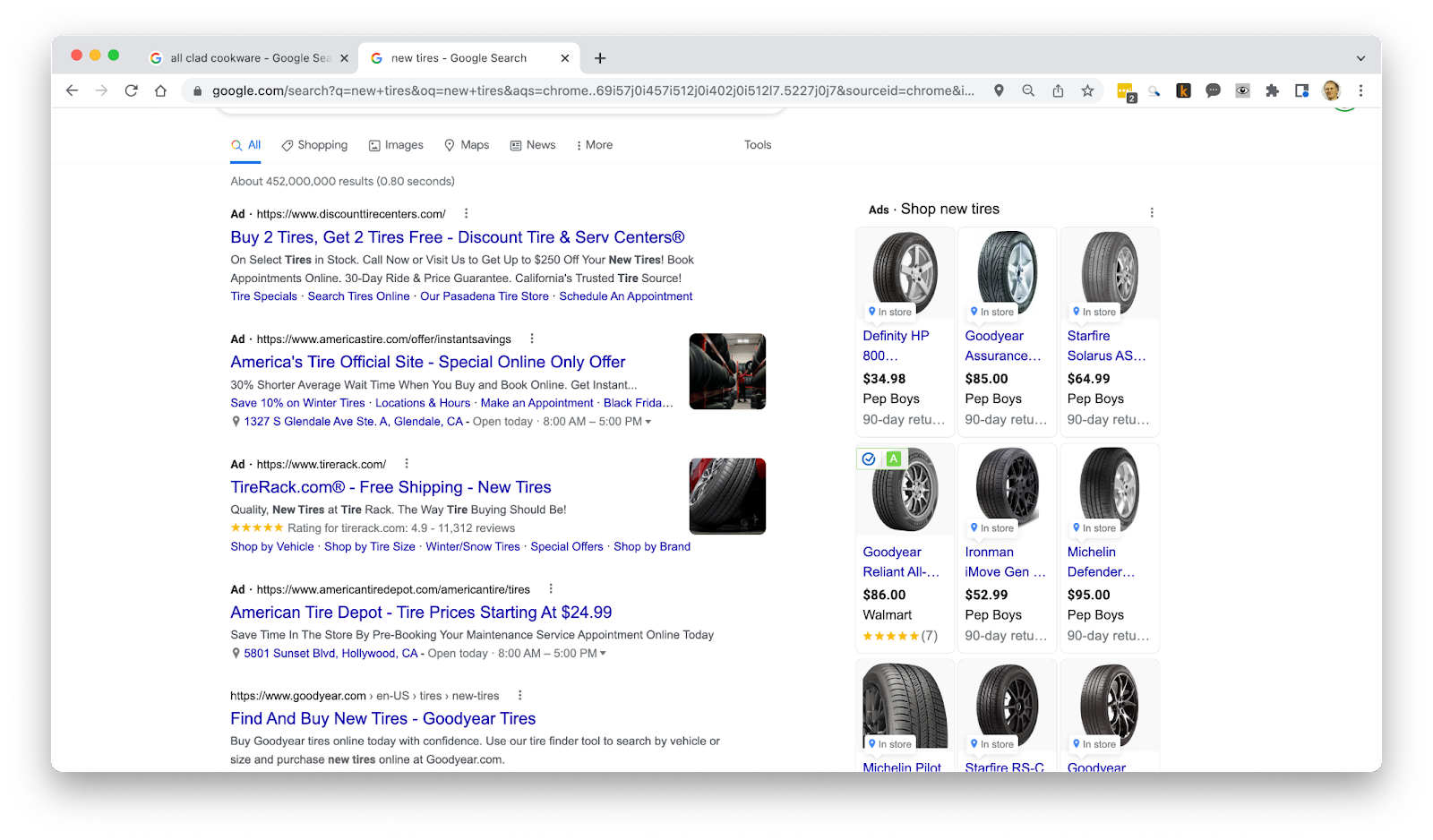

New Tires

An organic search for “new tires” might have been expected to show a listing of local tire shops near me. Instead, without scrolling it shows only ads, almost entirely from large retailers and major brands. This highlights how commercial results narrow the set of possible results to those most able to pay.

Note also that there are the now traditional ad units disguised to look like organic search results but flagged as “Ad” plus an image pack consisting of additional ads. There is only one organic result, at the very bottom of the visible portion of the page.

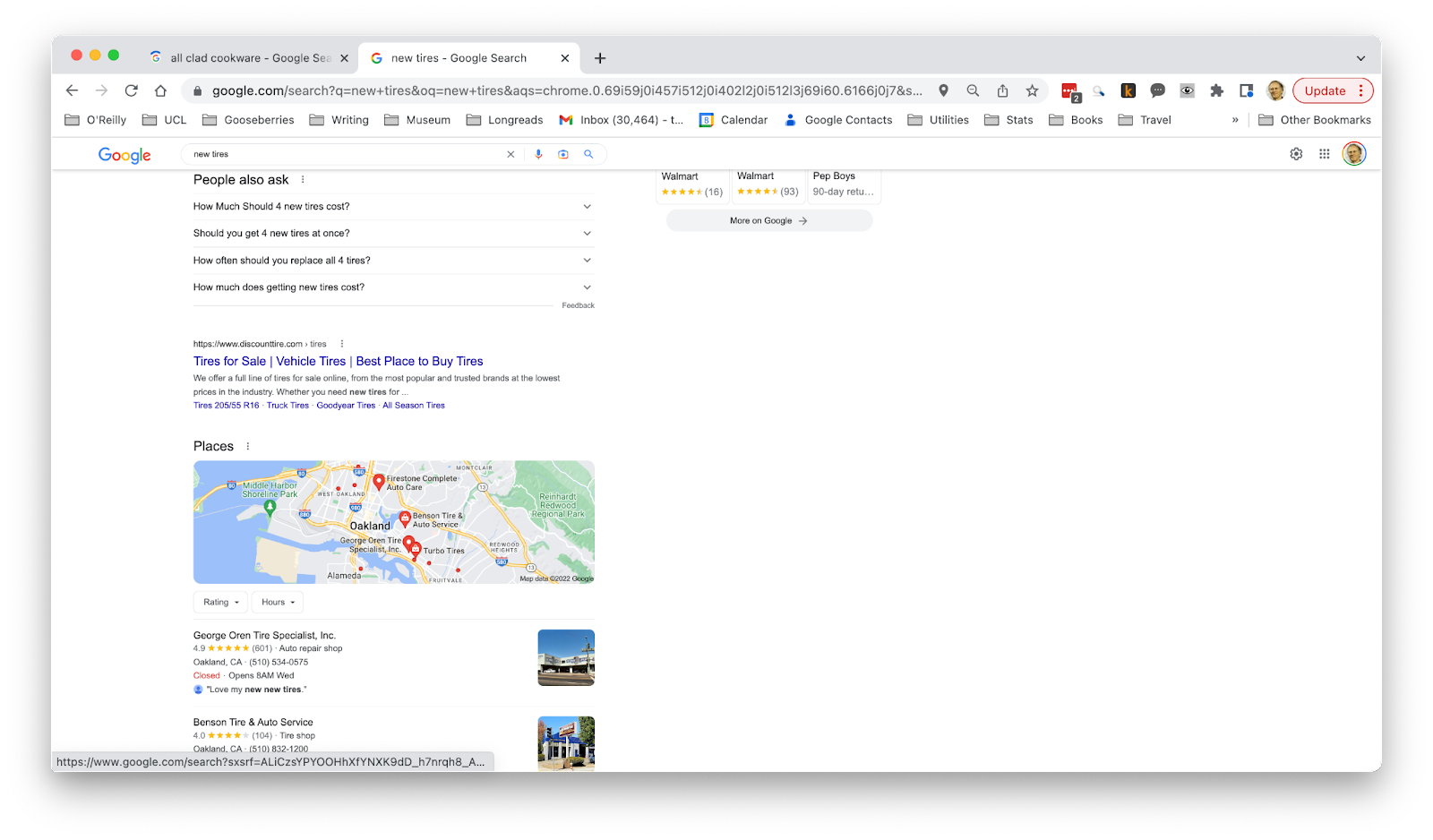

Scroll down, though, and it gets even more interesting. Here you see the role of query refinement as expressed through one of Google’s own products, Google Maps. This feature is ideal from the point of view of both users and local merchants, where someone is most likely to want to buy new tires. You would think, though, that if Google were relentlessly focused on user welfare, this display would be at the top right corner of the screen, as it is clearly the most relevant information. The fact that it is pushed below ads shows both how algorithmic choices shape the market (attention given first to large chains and online retailers because they advertise, rather than to local retailers) and how those choices appear to be made on the basis of profitability to the platform rather than user welfare.

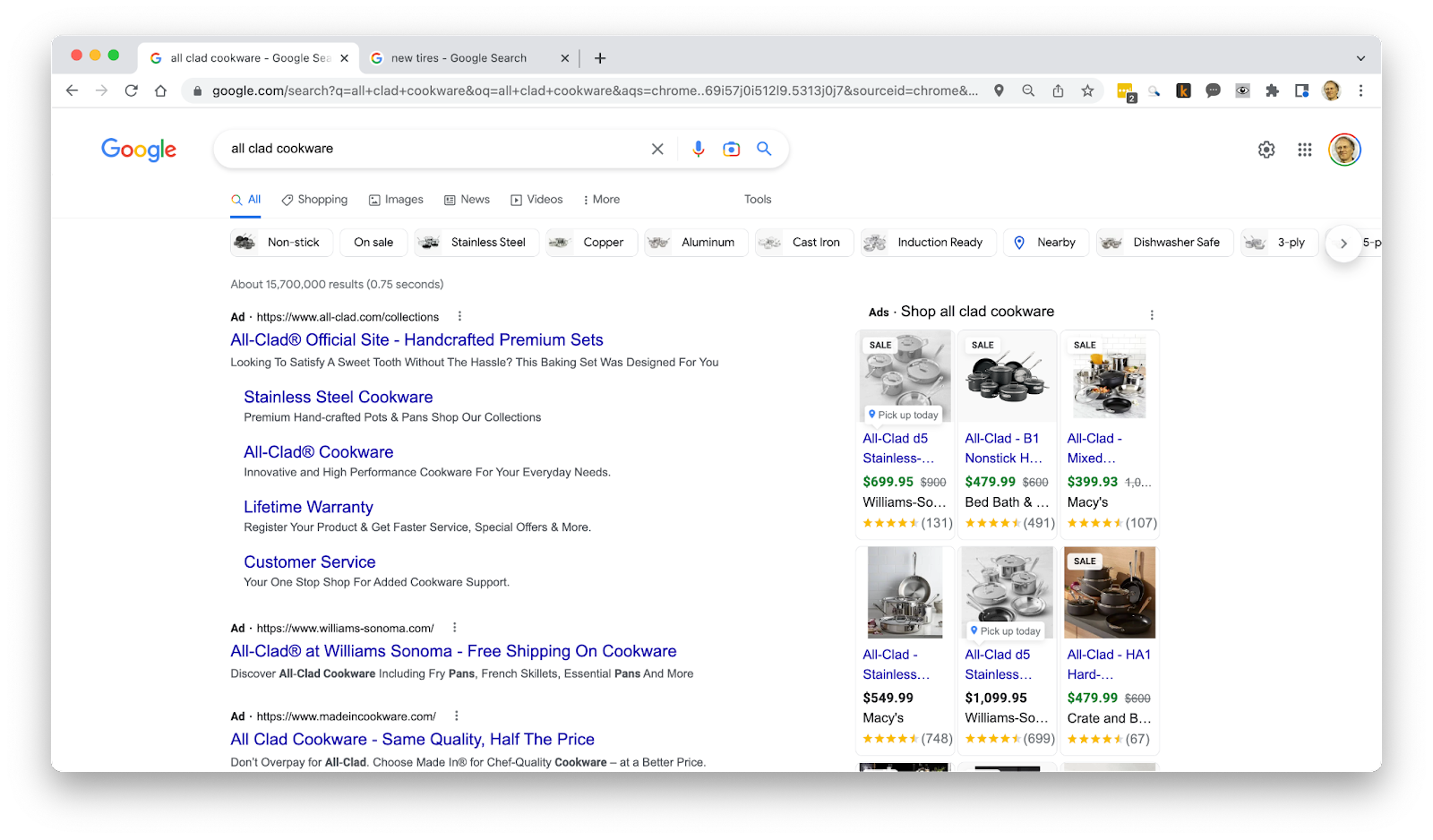

All Clad Cookware

A search for a product by brand name illustrates how Google fails to show organic results even when the user searches for a product by name. In order to get visibility that would otherwise be sold to competitors, the manufacturer must take out a series of ads for their own product, even though the customer is already looking for it. This might be justifiably called “pay to play.”

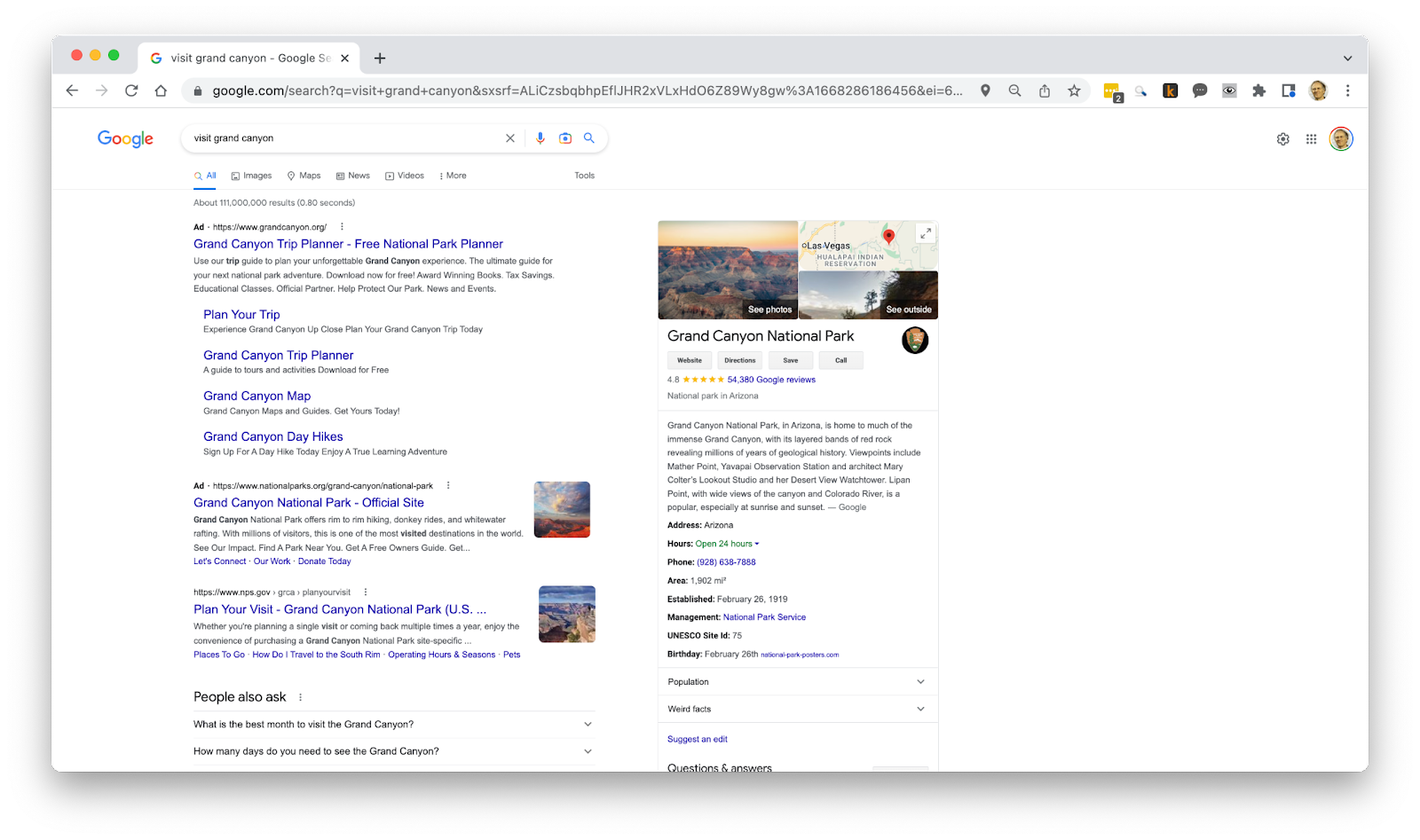

Visit Grand Canyon

Note below how Google has given over the right hand column to its own summary of information about the park, making it less likely that the user will need to click, or if they do, they will click through to other Google properties like Google Maps or Google’s own travel recommendation site (which competes with third party sites like TripAdvisor).

The left hand column is given over mostly to ads, with only one organic result shown, followed by “People also ask,” which is a query refinement feature designed to help the user navigate to additional information.

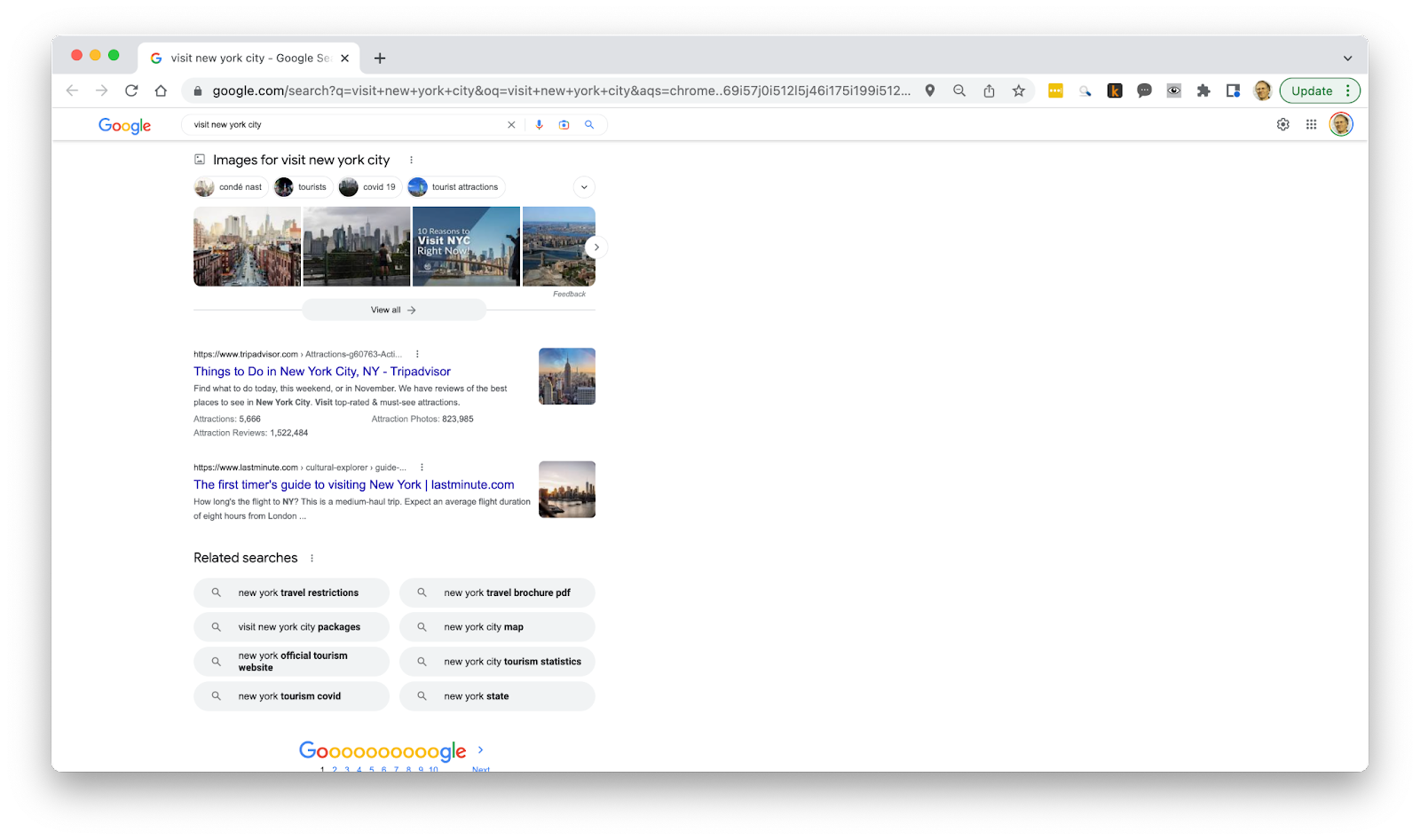

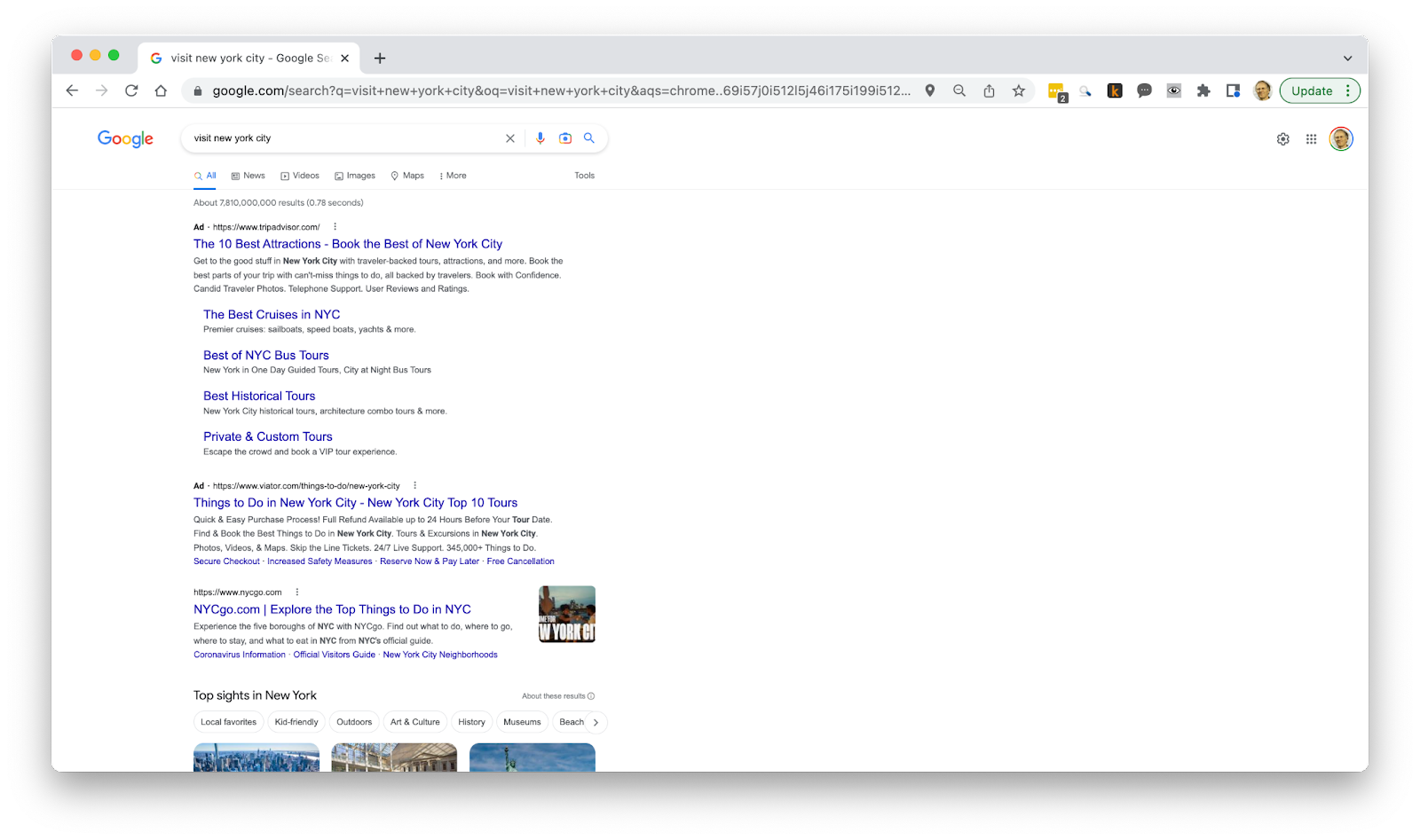

Visit New York City

A query for “visit New York City” is similarly dominated by ads, with only one organic result towards the bottom of the page. Note that the right hand column is left empty. There is plenty of room on the page for both ads and organic content, but Google has chosen to put the ads in the best position on the page and to push the organic results down the page. This illustrates how site design (really dynamic, algorithmic page-by-page design!) interacts with search algorithms to shape user attention.

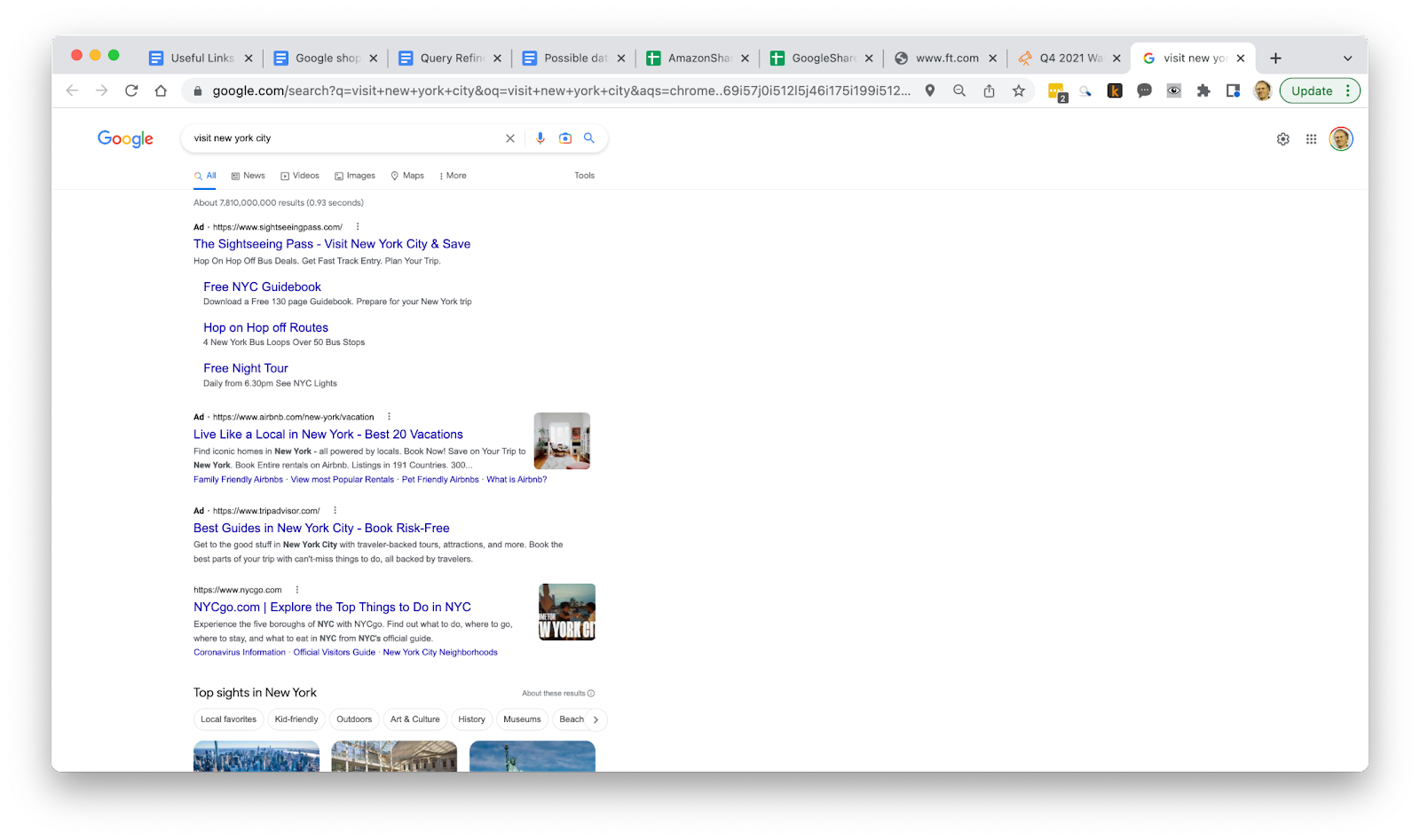

A second visit shows different ads, but as you can see, the sole organic result stays the same. This illustrates an important point: organic results stay the same because they are the result of an ongoing competition for the best content as determined by Google’s relevancy algorithms, while the ads are determined by an algorithmic ad auction that takes into account both price and possible relevancy as determined by Google’s estimate of the user’s likelihood to click the ad.

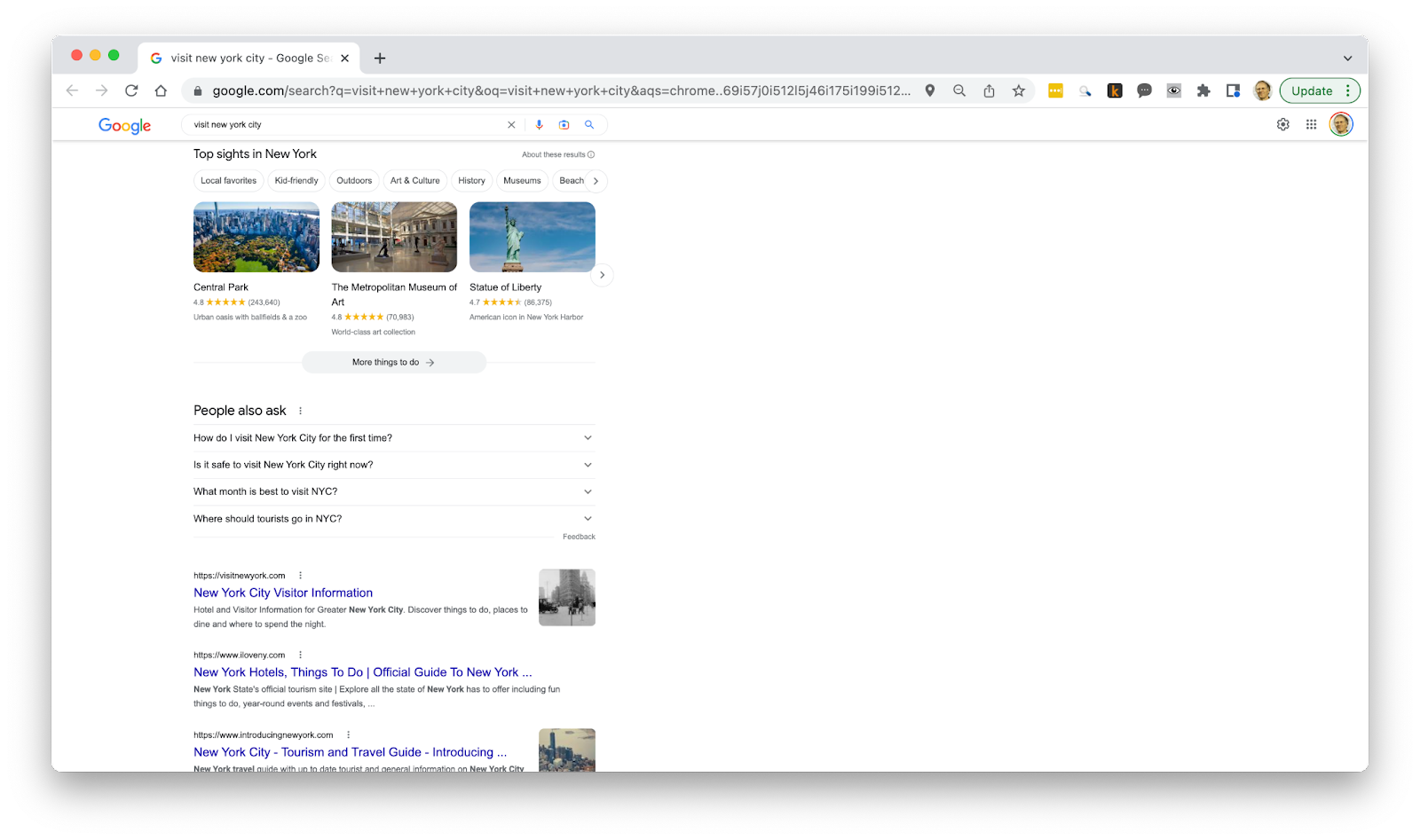

Continuing to scroll down the page you can see that additional organic results are pushed down by Google’s own content (an image pack showing selections from its own travel review service), then query refinement, and only then do we begin to see more organic results.

Continuing to scroll…

we eventually get to TripAdvisor’s organic result for this search, which occupies the seventh organic position, despite being in the first ad position in the very first screenshot shown above. This illustrates how inferior paid content can crowd out superior organic content in a system that does not show organic and paid content in parallel, as Google once did.