Machine money and people money

A conversation about Universal Basic Income with John Maynard Keynes and Paul Buchheit.

The machine works of Richard Hartmann in Chemnitz. (source: Scan by Norbert Kaiser. Via Wikimedia Commons.)

The machine works of Richard Hartmann in Chemnitz. (source: Scan by Norbert Kaiser. Via Wikimedia Commons.)

At the outset of the Great Depression, John Maynard Keynes penned a remarkable economic prognostication: that despite the ominous storm that was then enfolding the world, mankind was in fact on the brink of solving “the economic problem” — that is, the quest for daily subsistence.

The world of his grandchildren — the world of those of us living today — would, “for the first time…be faced with [mankind’s] real, his permanent problem — how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.”

It didn’t turn out quite as Keynes imagined. Sure enough, after a punishing Depression and a great World War, the economy entered a period of unparalleled prosperity. But in recent decades, despite all the remarkable progress of business and technology, that prosperity has been very unevenly distributed. Around the world, the average standard of living has increased enormously, but in modern developed economies, the middle class has stagnated, and for the first time in generations, our children may be worse off than we are. Once again, we face what Keynes called “the enormous anomaly of unemployment in a world full of wants,” with consequent political instability and uncertain business prospects.

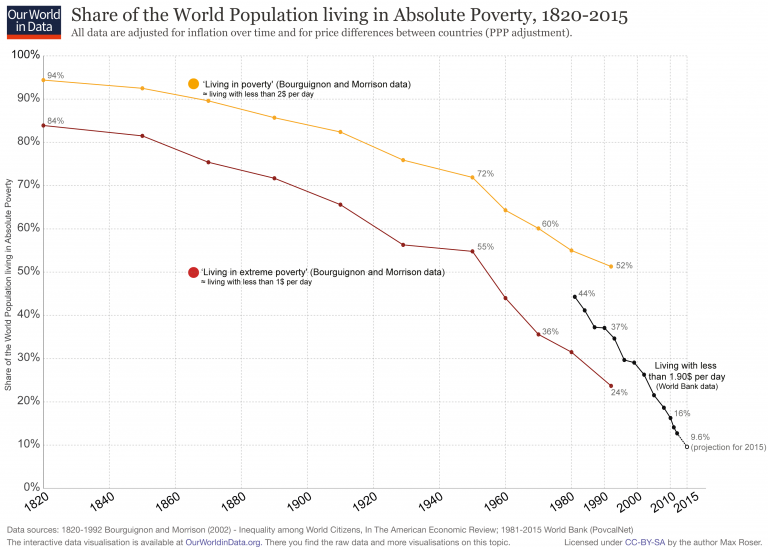

But Keynes was right. The world he imagined, where “the economic problem” is solved is, in fact, still before us. Global poverty has sunk to all time lows, and, if only we play our cards right, we could still enter the world Keynes envisioned.

As Max Roser, creator of Our World in Data, notes: “Even in 1981 more than 50% of the world population lived in absolute poverty — this is now down to about 14%. This is still a large number of people, but the change is happening incredibly fast. For our present world, the data tells us that poverty is now falling more quickly than ever before in world history.”

Much of Keynes’ essay, entitled “Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren,” concerns the issue of what people will do with their time when productivity has increased to the point where the machines do all the work.

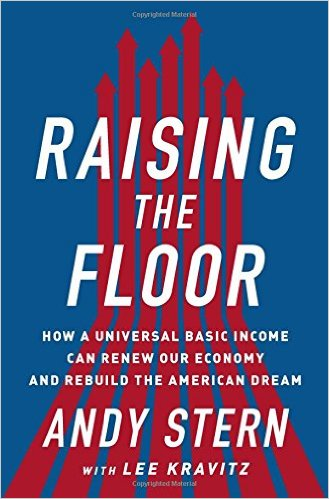

That question has resurfaced in today’s discussions about Universal Basic Income. Fabled labor leader Andy Stern left his job as the head of the SEIU to write a book making the case for UBI; Y Combinator Research is planning a pilot program in Oakland, CA; and the question of Universal Basic Income has actually come to a vote in Switzerland. The proposal was soundly defeated, but the fact that it was considered seriously tells us how far the idea has come since it was proposed by Thomas Paine in 1795, and more recently by Milton Friedman in 1962 (and Paul Ryan in 2014.)

I’d like to talk through some key paragraphs from Keynes’ essay, and reflect on their truth as seen in today’s headlines. Think of this as the conversation I’d be having with Keynes if he were still around to have it. Then I’ll weave in some thoughts from a recent conversation with Y Combinator’s Paul Buchheit about these same ideas. These are half-formed thoughts, not polished conclusions. I’d welcome your feedback!

Keynes’ essay opens:

“We are suffering just now from a bad attack of economic pessimism. It is common to hear people say that the epoch of enormous economic progress which characterised the nineteenth century is over; that the rapid improvement in the standard of life is now going to slow down; that a decline in prosperity is more likely than an improvement in the decade which lies ahead of us. I believe that this is a wildly mistaken interpretation of what is happening to us. We are suffering, not from the rheumatics of old age, but from the growing-pains of over-rapid changes, from the painfulness of readjustment between one economic period and another….”

Sure enough, we are indeed once again hearing the chorus of pessimism and doubt. Automation is going to destroy white collar jobs in the same way it once destroyed factory jobs.We have an economy that relies on growth, but the age of growth is over. We are in the age of “secular stagnation.” And so on.

Keynes presciently gave a new name to the heart of our current angst:

“We are being afflicted with a new disease of which some readers may not yet have heard the name, but of which they will hear a great deal in the years to come — namely, technological unemployment. This means unemployment due to our discovery of means of economising the use of labour outrunning the pace at which we can find new uses for labour. But this is only a temporary phase of maladjustment.”

Like Keynes, I remain optimistic. If we play our cards right, this can be only “a temporary phase of maladjustment.” There may be enormous dislocation, but we will come through it in the end. Keynes wrote:

“The prevailing world depression, the enormous anomaly of unemployment in a world full of wants, the disastrous mistakes we have made, blind us to what is going on under the surface….”

“The enormous anomaly of unemployment in a world full of wants.” I love that phrase! As Nick Hanauer has said to me, “Technology is the solution to human problems. As long as we haven’t run out of problems, we won’t run out of work.”

There is so much left to do: dealing with the enormous transitions to our energy infrastructure that will be required to respond to climate change, the public health challenges of new infectious diseases, the demographic inversion in which a growing class of elders will be supported by a smaller cohort of workers, rebuilding the physical infrastructure of our cities, providing clean water to the world, feeding, clothing, and entertaining 9 billion people.

Note that Nick said “we won’t run out of work,” not “we won’t run out of jobs.” Part of the problem is that “the job” is an artificial construct, in which work is managed and parceled out by corporations and other institutions, to which individuals must apply to participate in doing the work. Financial markets are supposed to reward corporations to pursue work that needs doing. But as Rana Foroohar has noted in her excellent new book Makers and Takers: The Rise of Finance and the Decline of American Industry, there is a growing divergence today between what financial markets reward and what the economy really needs.

Because corporations have different motivations and constraints than individuals, it is possible that a corporation is not able to offer “jobs” even as “work” goes begging. Because of the structure of employment, in uncertain times, companies are hesitant to take on workers until they are sure of demand. And because of the demands of financial markets, companies often find short-term advantage in cutting employment, since driving the stock price gives owners a better return than actually employing people to get work done. Eventually “the market” sorts things out (in theory), and corporations are once again able to offer jobs to willing workers. But there is a lot of unnecessary friction.

One of the challenges of the Next Economy is to create new mechanisms that make it easier to connect people and organizations to work that needs doing — a more efficient marketplace for work. And you can argue that that is one of the key drivers at the heart of the on-demand revolution that includes companies like Uber and Lyft, DoorDash and Instacart, Upwork, Handy, TaskRabbit, and Thumbtack. The drawbacks of these platforms in providing consistent income and a social safety net shouldn’t blind us to what does work about them. We need to improve these platforms so that they truly serve the people who find work through them, not try to turn back the clock to the guaranteed employment structure of jobs in the 1950s.

There is also a leadership challenge: to correctly identify work that needs doing. We need companies to take on visionary projects that are not being solved by the market “as it is” but that instead reshape the market. Think of what Elon Musk has done to catalyze new industries with Tesla, SpaceX, and SolarCity, or what Google did with “access to all the world’s information,” or what the Gates Foundation is doing to eliminate malaria. Markets are not infallible. Government can play a role here, as it did with the Internet, GPS, and the Human Genome Project. And government’s role is not limited just to projects that require coordinated effort beyond the capability of even the largest commercial actors. Government must deal with market failure. This can be the failure of the commons, outright malfeasance by commercial actors, or problems with financial markets such as the the one that is still strangling the economy today.

But Keynes’ essay gets even more interesting. Let’s repeat the lines quoted above and match them with their conclusion:

“The prevailing world depression, the enormous anomaly of unemployment in a world full of wants, the disastrous mistakes we have made, blind us to what is going on under the surface….for the first time since his creation man will be faced with his real, his permanent problem — how to use his freedom from pressing economic cares, how to occupy the leisure, which science and compound interest will have won for him, to live wisely and agreeably and well.”

In a recent conversation, Paul Buchheit, creator of Gmail and now a partner at Y Combinator, said something really provocative: “There may need to be two kinds of money: machine money, and human money. Machine Money is what you use to buy things that are produced by machines. These things are always getting cheaper. Human Money is what you use to buy things that only humans can produce.”

Paul continued: “The key thing that humans offer that machines do not is ‘authenticity’. You could buy a machine made table from Amazon for cheap, or a hand crafted table from a person for much more (and for real authenticity, we want it to come from a local artisan, not an anonymous factory worker on the other side of the world). In the long term, the price of the former (in machine money) should trend towards zero, but the latter will always cost about the same in human money (some quantity roughly proportional to the number of hours required to make it).”

Paul argues that the right name for what many are calling “Universal Basic Income” should be “the citizen’s dividend.” This concept traces back to ancient Athens, and in America to the writings of Thomas Paine. In Paine’s conception, the dividend was based on shared ownership of natural resources — and this is just what we’ve already seen done in a country like Norway, in Alaska, and in a notable experiment during the 1970s, in a small town in Manitoba.

Where Paine argued that every citizen had a right to the underlying value of unimproved land, Buchheit suggests that all of mankind should have some claim on the fruits of technological progress. That is, we should use tax policy to capture some amount of the bounty from machine productivity, and provide that to all people as a stipend with which they can meet the needs of everyday existence. This bounty should be distributed sufficiently that everyone can have enough “Machine Money” to meet their basic needs. Meanwhile, that machine productivity should also provide those goods at ever lower costs, increasing the value of the citizen’s dividend. This is the world of prosperity that Keynes envisioned for his grandchildren.

How might we pay for a Universal Basic Income? The amount required is greater than the cost of all current social programs. In a separate conversation, Y Combinator chief Sam Altman explained that those who argue about how we would pay for it today miss the point. “I am confident that if we need it, we will be able to afford it,” he said at a recent event on UBI at Bloomberg Beta with Andy Stern and the Aspen Institute’s Natalie Foster. One major factor that isn’t being considered, as he expanded on it in our subsequent conversation, is that the possible productivity gains from technology are enormous, and these gains can be used to reduce the cost of any goods produced by machines — what costs $35,000 today might cost $3,500 in a future where the machines have put so many people out of work that a Universal Basic Income is required. This is why Paul argues for “machine money.” In a profound way, its value inflates not as a currency normally inflates, but because the lower costs provided by machine productivity constantly increase its purchasing power.

What is “Human Money” For?

I love Paul’s distinction between two types of money, but I do wonder whether it’s complete. His notion of Human Money encompasses two very different classes of goods and services: those that involve a true human touch — parenting, teaching, caregiving of all kinds — and those that involve creativity.

Perhaps “Human Money” needs to be further subdivided into “Caring Money” and “Creativity Money.”

Caring is a necessity of life, just as is food and shelter, and should not be denied to anyone in a just society. In an ideal world, caring is a natural outgrowth of family and community, as we care for those we love, but there is also a caring economy of professionals, including teachers, doctors, nurses, eldercare assistants, babysitters, hairdressers, and masseusses. And in a society with an inverted demographic pyramid, in which there are far more of the elderly than young people to support them, as we will see in many developed countries in by 2050, machines may help to fill this gap.

Creativity Money is what we pay for the good things of life beyond the basics. The latest LeBron James basketball shoe. Adele’s “Hello.” The glass of wine with friends. The night out at the movies. The beautiful dress and the sharp suit. Sports, music, art, storytelling, and poetry.

It is a mistake to think that “the creative economy” is limited to entertainment and the arts. People at all levels of society pay a premium over the base cost of goods as a way of expressing and experiencing beauty, status, belonging, and identity. Creativity Money is what someone pays for the difference between a Mercedes C-Class and a Ford Taurus, for a meal at The French Laundry rather than the local French bistro, or at that same bistro rather than at a McDonald’s. It is why those who can afford it pay $5 for an individually crafted cappuccino rather than drinking Folgers instant coffee from a 5-pound can, as our parents did. It is why we pay huge prices or wait years to see Hamilton, while tickets for the local dinner theater are available right now.

Creativity Money is the focus of a competition as intense as any that characterizes the Machine Money economy. It is already at the heart of huge swaths of our economy: industries like fashion, real estate, luxury goods, all depend on the competition among people who are already rich to own more, to enjoy or sometimes just to show off their wealth.

In the late 18th century, in his short novel Rasselas, Samuel Johnson wrote:

“But for the Pyramids, no reason has ever been given adequate to the cost and labour of the work. The narrowness of the chambers proves that it could afford no retreat from enemies, and treasures might have been reposited at far less expense with equal security. It seems to have been erected only in compliance with that hunger of imagination which preys incessantly upon life, and must be always appeased by some employment. Those who have already all that they can enjoy must enlarge their desires. He that has built for use till use is supplied must begin to build for vanity, and extend his plan to the utmost power of human performance that he may not be soon reduced to form another wish.”

That is, even in a world where every need is met, there will still be “a world full of wants.” Keynes wrote of this kind of competition too in “Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren”:

“Now it is true that the needs of human beings may seem to be insatiable. But they fall into two classes — those needs which are absolute in the sense that we feel them whatever the situation of our fellow human beings may be, and those which are relative in the sense that we feel them only if their satisfaction lifts us above, makes us feel superior to, our fellows. Needs of the second class, those which satisfy the desire for superiority, may indeed be insatiable; for the higher the general level, the higher still are they. But this is not so true of the absolute needs — a point may soon be reached, much sooner perhaps than we are all of us aware of, when these needs are satisfied in the sense that we prefer to devote our further energies to non-economic purposes.”

Given an income sufficient to the necessities of life, some people will choose to step off the wheel — to spend more time with family and friends, in creative pursuits, or whatever they damn well please. But even in a world where the machines do most of the essential work, the competition for additional Creativity Money will drive the economy.

Keynes foresaw both of these possibilities. He wrote:

“The strenuous purposeful money-makers may carry all of us along with them into the lap of economic abundance. But it will be those peoples, who can keep alive, and cultivate into a fuller perfection, the art of life itself and do not sell themselves for the means of life, who will be able to enjoy the abundance when it comes.”

And this is the interesting bit. Creativity can be the focus of an intense competition for status, so that “he who has built for use till use is supplied must begin to build for vanity.” But it can also be the key to a future human economy that would let all enjoy the fruits of leisure that are brought to us by machine productivity.

The good life consists in enjoying the creativity of others, and in sharing our own, not just in having our basic needs met. Much of this, like caring, is a natural outgrowth of a successful human society, not an economic pursuit.

Creativity, and the patronage of creativity, may be a major component of the future economy.

In this regard, I’m fascinated by a comment that Hal Varian, Google’s chief economist, made to me over dinner one night: “If you want to understand the future, just look at what rich people do today.” (He’s also made that same comment in writing, on more than one occasion.) It’s easy to think of this as a heartless libertarian comment. Our dinner companion, Hal’s former student Carl Shapiro, fresh from his stint at Obama’s White House Council of Economic Advisers, seemed horrified. But when you think about it for a moment, it makes a lot of sense.

Dining out was once the province of the wealthy. Now far more people do it. In our most vibrant cities, a privileged class experiences a taste of a future that could be the future for everyone. Restaurants compete on the basis of creativity and service, “everyone’s private driver” whisks people around in comfort from experience to experience, and one-of-a-kind boutiques provide unique consumer goods. Rich people once took the European Grand Tour; now soccer hooligans do it. Cell phones, designer fashion, entertainment have all been democratized. Mozart had the Holy Roman Emperor as his patron; Kickstarter, GoFundMe, and Patreon extend that opportunity to millions of ordinary people.

New industries driven by the human touch are everywhere. In the US, more than 4,200 craft breweries now make up more than 10% of the market, and command a price double that of a mass-produced beer. In the first quarter of 2016, 25 million customers purchased hand-crafted and artisan goods on Etsy. These are small green shoots in an economy dominated by mass-produced products, but they teach us something important about the future.

What is happening in entertainment may be an even more interesting harbinger. While blockbusters still dominate in Hollywood and New York publishing, a larger and larger proportion of people’s entertainment time is spent on social media, consuming content created by their friends and peers. That profound shift in media consumption has most visibly enriched Facebook, Google, and the current generation of media platforms, but it is increasingly turning into a real job for a larger and larger number of individual media creators.

As YouTube star and VidCon impresario Hank Green wrote recently:

“I started paying my bills with YouTube money around the time I hit a million views a month. My content was admittedly low budget and “views” isn’t necessarily the best metric (what it means changes drastically based on platform), but I want you to take a guess at how many YouTube channels now get more than a million views a month? A couple hundred? A thousand?

How about 37,000.

For context, Facebook has 12,000 employees….

If “internet creator” were a company, it would be hiring faster than any company in silicon valley.”

Keep in mind that “YouTube Money,” as Hank names it, is only one of many new forms of Creative Money that are available via online platforms. There’s Facebook Money, Etsy Money, Kickstarter Money, App Store money, and more.

Some of these marketplaces are further along than others in creating opportunities for individuals and small companies to convert attention (the raw material of Creativity Money) into cash. The next few years will see an explosion of startups that find new ways to convert more and more of the attention that is spent online into traditional money.

As Jack Conte, half of the musical duo Pomplamoose and founder and CEO of crowdfunding patronage site Patreon, told me, he founded Patreon after “Nataly and I got 17 million views of one of our music videos, and it turned into $3,500 in ad revenue. Our fans value us more than that.”

As crowdfunding sites like Patreon (and, of course, Kickstarter and IndieGoGo) show, there are increasingly new opportunities for ordinary people to compete for real currency, not just attention, in the creative economy. These sites are still a relatively small part of the overall economy, but they have a lot to teach us about its possible future direction.

For more reading about the shape of the Next Economy, subscribe to the Next:Economy newsletter.