Designing delivery: From industrialism to post-industrialism

In a post-industrial economy, the focus shifts from selling products to helping customers accomplish their goals through service. Excerpt from Jeff Sussna's book, "Designing Delivery."

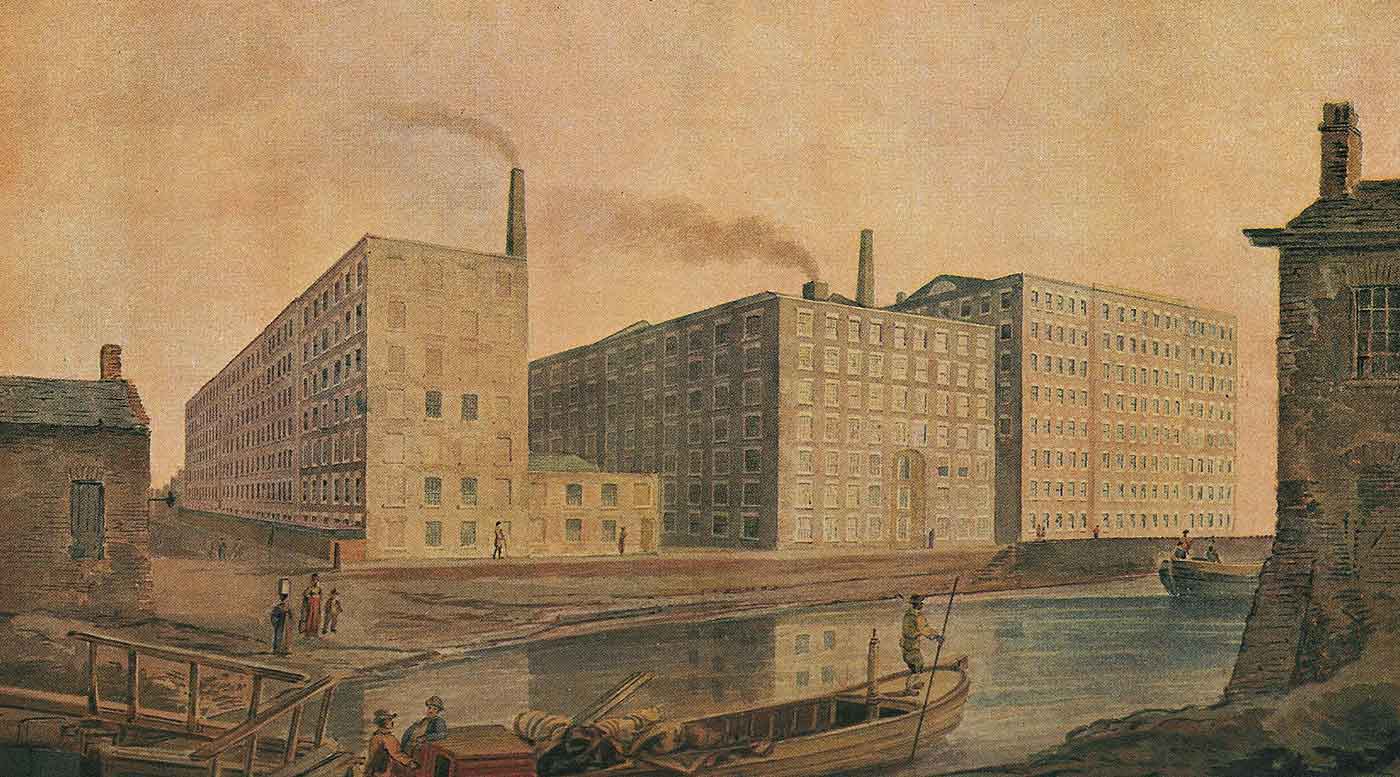

McConnel & Company mills, about 1820 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

McConnel & Company mills, about 1820 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

From Industrialism to Post-Industrialism

In 1973, Daniel Bell published a book called The Coming of Post-Industrial Society. In it, he posited a seismic shift away from industrialism toward a new socioeconomic structure which he named post-industrialism. Bell identified four key transformations that he believed would characterize the emergence of post-industrial society:

- Service would replace products as the primary driver of economic activity

- Work would rely on knowledge and creativity rather than bureaucracy or manual labor

- Corporations, which had previously strived for stability and continuity, would discover change and innovation as their underlying purpose

- These three transformations would all depend on the pervasive infusion of computerization into business and daily life

If Bell’s description of the transition from industrialism to post-industrialism sounds eerily familiar, it should. We are just now living through its fruition. Every day we hear proclamations touting the arrival of the service economy. Service sector employment has outstripped product sector employment throughout the developed world, according to World Bank.

Companies are recognizing the importance of the customer experience. Drinking coffee has become as much about the café and the barista as about the coffee itself. Owning a car has become as much about having it serviced as about driving it. New disciplines such as service design are emerging, which use design techniques to improve customer satisfaction throughout the service experience.

Disruption is driving 100-year-old, blue-chip companies out of business. Startups that rethink basic services like hotels and taxis are disrupting entire industries. Innovate or die is the business mantra of the day. Companies are realizing the need to empower their employees’ creative decision-making abilities, and are transforming their organizational structures and communications tools in order to unleash internal innovation and collaboration.

IT is moving beyond playing a supporting role in business operations; it’s becoming inseparable from it, to the point where every business is becoming a digital business. One would expect a company that sells heating and ventilation systems to specialize in sheet aluminum and fluid dynamics. You couldn’t imagine a more physical-world industry. Yet HVAC suppliers have begun enabling their thermostats with web access in order to generate data for analytics engines that automatically fine-tune heating and cooling cycles for their customers. As a result, they’re having to augment their mechanical engineering expertise with skills in building and running large-scale distributed software systems.

From Products to Service

The Industrial Age focused on optimizing the production and selling of products. Interchangeable parts, assembly lines, and the division of labor enabled economies of scale. It became possible to manufacture millions of copies of the same object. Modern marketing evolved to convince people to buy the same things as one another. Consumerism brought into being a world where people evaluated their lives by what they had, rather than how they felt.

A product economy functions in terms of transactions. A sneaker company, for example, calculates how many units they think they can sell, at what price point, to whom. They create a marketing campaign to drive the desired demand. They link their production and distribution systems to that forecast.

The consumer, for her part, comes home from a run with sore feet and decides she needs a new pair of running shoes. She goes to the local athletic store and tries on a few different kinds of shoes. At some point, she makes a decision and buys something, at which time the transaction is concluded.

In addition to being transaction-oriented, a product economy relies on a push marketing model. Companies use the Four P’s (Production, Price, Promotion, and Place) to treat marketing like an “industrial production line that would automatically produce sales.”1 According to this model, proper planning almost predestines the customer to drive to a certain store, try on certain shoes, and make a certain purchase.

The twentieth-century media model developed hand in hand with consumerist marketing. Broadcast television evolved as the perfect medium for companies to try to convince consumers that they needed a particular product. The very words broadcast and consumer reveal the nature of the relationship between industrial production and marketing.

A post-industrial economy shifts the focus from selling products to helping customers accomplish their goals through service. Whereas products take the form of tangible things that can be touched and owned, service happens through intangible experiences that unfold over time across multiple touchpoints. Consider the example of flying from one city to another. The experience begins when you purchase your ticket, either over the phone or via a website. It continues when you arrive at the airport, check your bags, get your boarding pass, find your gate, and wait for boarding to begin.

Only after you board does the flight actually begin. You buy a drink and watch a movie. Finally the plane lands; you still have to disembark and collect your luggage. The actual act of flying has consumed only a small part of the overall trip. In the process of that trip, you have interacted with ticket agents, baggage handlers, boarding agents, and flight attendants. You have interfaced with telephones, websites, airport signage, seating areas, and video terminals.

Unlike product sales, which generate transactions, service creates continuous relationships between providers and customers. People don’t complain about an airline on Twitter because their flight was delayed. They complain because as usual their flight was delayed. Perhaps instead they remark on the fact that, for once, their flight wasn’t delayed.

Service transforms the meaning of value. A product-centric perspective treats value as something to be poured into a product, then given to a customer in exchange for money. If I buy a pair of sneakers but leave them in my closet and never wear them, I don’t feel entitled to ask for my money back.

Service value only fully manifests when the customer uses the service. The customer co-creates value in concert with the service provider. The fact that an airline owns a fleet of airplanes and sells you a ticket for a seat on one of them doesn’t by itself do you any good. The value of the service can’t be fully realized until you complete your flight. You and the airline—and its ticket agents, pilots, flight attendants, and baggage personnel—all have to work together in order for the flight to be successful. The goals, mood, situation, and surrounding experiences you bring with you all contribute to the success of the service experience.

Service changes the dynamic between vendor and consumer, and between marketer/salesperson and buyer. In order to help customers accomplish a goal, you need to understand their goals, and what they bring to the experience. In order to do that, you need to be able to listen, understand, and empathize. Service changes marketing from push to pull.

Marketers are beginning to adapt to this new model. They are recognizing that strategies like content marketing fail to provide sufficient visibility into the mind of the consumer. Some organizations are supplementing content with marketing applications. These applications flip the Four P’s on their head, and give marketers meaningful customer insight through direct interaction.

Astute readers will notice the need for an even larger network of collaboration. The airline operates within an airport, which operates within a city. A successful trip therefore also needs help from security agents and road maintenance crews. High-quality services address the larger contexts in which they co-create value with customers.

Sun Country, for example, is a regional airline headquartered in Minneapolis. Those of us who live in Minneapolis know that Minnesota has two seasons: winter and road construction. Sun Country recognizes that road construction can cause driving delays, so warnings are posted on the home page of its website about construction-related delays on routes leading to the airport.

Sun Country understands that, although the roads around the airport are beyond its control, it can still impact the perceived quality of the service experience. If I arrive at the gate late and feeling harried, I’ll have less patience for any mistakes on the part of the ticket agent. I’ll more likely find fault with the airline, regardless of who’s truly at fault.

The Internet and social media are accelerating the transformation of the marketing and sales model by upending the customer-vendor power structure. Customers now have easy access to as much if not more information about service offerings and customer needs than the vendors themselves. Facebook and Twitter instantly amplify positive and negative service experiences. Customer support is being forced out onto public forums. Companies no longer control customer satisfaction discussion about their products. Instead, they are becoming merely one voice among many.

From Discrete to Infused Experiences

It used to be relatively straightforward to know where in your life you were and what you were doing at any point in time. You were either at home or at work, or else driving between them. If you wanted to hang out with friends, you went to the mall. If, on the other hand, you wanted to be alone, you went in your room and shut the door. If you wanted to surf the Internet, you sat down at a desk in front of a computer. If not, you went out for a walk or a drive.

Now, though, the parts of our lives are melding together and infusing one another. Do you go to the coffee shop to chat or to work? Do you use your phone to call your mom, or to upload photos of your cat to Instagram, or to check your office email? Do you go to the library to peruse hardcover books on shelves, or to read ebooks on websites? Do you use your car for transportation, or as an incredibly complicated and expensive online music player? The answer to all of these questions is “yes.”

Even in the digital domain, our daily activities and the tools we use to accomplish them are blending together. We use the same phones, laptops, and cloud services to manage personal and business data. We check our Facebook accounts from work, and read our work email at the kitchen table. We use Twitter to maintain both friendships and professional networks.

Digital infusion has fully blossomed. The word infusion refers to the fact that computer systems are no longer separate from anything else we do. The digital realm is infusing the physical realm, like tea in hot water. Or, as Paolo Antonelli, Senior Curator of Architecture and Design for the Museum of Modern Art in New York, put it, “We live today, as you know very well, not in the digital, not in the physical, but in the kind of minestrone that our mind makes of the two.”

We encounter fewer and fewer situations that are purely physical. When I go shopping for a new refrigerator, I’m likely to read a review of it on my smartphone while I’m looking at it on the showroom floor. IKEA has integrated its paper catalog with its mobile app. If I use my phone to take a picture of an item in the catalog, the app will bring up more detailed, interactive information about the item in question.

Digital infusion means that brick-and-mortar retailers like Sears and IKEA, which traditionally specialized in the in-store experience, now must also offer equally compelling online experiences. To make things even more challenging, customers expect seamless experiences across physical and virtual channels: stores, kiosks, web browsers, tablets, phones, cars, and so on. As a result, companies are having to expand their marketing, design, and technology expertise to bridge the physical and digital domains.

The digital realm has moved beyond an isolated, contained part of our lives to become the underlying substrate upon which we carry out all of our activities and interactions. With the emergence of the Internet of Things, the digital realm is beginning to completely surround us. Our walls have connected thermostats. Our arms have connected watches. Our lawns have connected sprinkler systems. Our cars have connected dashboards.

In order to serve this newly infused world, companies need to undertake equally deep internal transformations. IT used to be a purely internal corporate function. IT might impact internal operations efficiency, but from the consumer’s perspective, it remained invisible—literally behind the scenes—like an automobile assembly line. The ease or pain with which employees shared marketing documents, filed expense reports, or tracked vendor purchase orders was of no concern to the customer.

Infusion breaks down the boundaries between internally facing systems of record and externally facing systems of engagement. The relational, continuous, collaborative nature of service means that internal company operations are inseparable from customer service. In a digitally infused business, therefore, IT becomes an integral part of the customer-facing service. In order for a customer to be able to upgrade a service subscription, for example, a public website may need to interact in real time with a back-office enterprise resource planning (ERP) system. If that ERP system is slow or incapable of providing important data to the website, its failures will become visible to the customer.

The virtualization of experience dramatically raises the stakes for digital service quality. Quality becomes that much more important because people depend on digital services for their very ability to function. If I can’t transfer money over the Web from my savings account to my checking account, I might bounce my rent check. If the software in my thermostat has a bug, I can’t warm up my house on a cold day. If my corporate ERP system goes down, my customers might not be able to log into their accounts.

From Complicated to Complex Systems

Digital infusion changes not just the way we experience things but also the way we organize, construct, and operate them. If the music player in your car isn’t working, is it Honda’s fault or Pandora’s? If you can’t watch a video on Friday night, is it Netflix’s, or Comcast’s, or Tivo’s fault? If you’re a freelancer, do you work for yourself, your client, or the broker who got you the gig? Is your invoicing data managed by your accounting SaaS provider, the PaaS on top of which they run, or the IaaS on top of which that PaaS runs? If you have a problem with something you bought, do you call the company’s customer support line, or do you just post your question or complaint on Facebook or Twitter?

Infusion breaks down familiar boundaries and structures. No longer can customers assume that Honda will transparently manage all of its vendors in order to deliver a working car, or be able to fix problems with any of its parts. Conversely, Honda can no longer assume it controls the communications channels with its customers.

This dissolving of boundaries impacts IT structures as well. If a customer can’t log in to your website, is the problem caused by the web server or the mainframe finance system that holds the customer record? The new requirement for interconnectivity between systems of record and systems of engagement complicates network and security architectures. So-called rogue or shadow IT, where business units procure cloud-based IT services without the participation of a centralized IT department, makes it harder to control or even know which data lives inside the corporate data center and which lives in a cloud provider’s data center.

Infusion forces homogeneous, hierarchical, contained systems to become heterogeneous, networked, fluid, and open-ended. In other words, complicated systems become complex ones. People often use the words complicated and complex interchangeably. When applied to systems, however, they mean very different things, with very different implications for defining and achieving quality. We therefore need to understand the distinction between them.

Complicated Systems

A complicated system can have many moving parts. A car contains something on the order of 30,000 individual parts. All 30,000 parts, however, don’t directly interact with one another. The fuel system interacts with the engine, which interacts with the drivetrain. The fuel system consists of a fuel tank, fuel pump, and carburetor. The carburetor is made up of jets, float bowls, gaskets, and so on.

Complicated systems arrange their components into navigable, hierarchical structures that facilitate understanding and control. Very few of us can fix our own cars anymore. We can still, though, reasonably understand their overall structure. If our car has a flat tire, and the service technician tells us we need a new carburetor, we know enough to suspect that something fishy is going on.

The interactions within complicated systems don’t dynamically change. The carburetor doesn’t suddenly start directly interacting with the tires. Furthermore, complicated systems behave coherently as wholes. If you’re driving your car, and you turn the steering wheel to the left, the entire car goes to the left. One of the doors doesn’t decide to wander off in the opposite direction.

Complex Systems

Complex systems, on the other hand, consist of large numbers of relatively simple components that have fluid relationships with many other components. Examples of complex systems include everything from ant colonies to companies to cities to economies. You can’t really define an economy, for example, as a neat hierarchy, with the Chair of the Federal Reserve at the top, the Fortune 500 below that, and small businesses and sole proprietors at the bottom.

Instead, companies and individuals dynamically create and dissolve business relationships with one another on multiple levels. I hire a plumber. A large company buys a smaller one. An executive quits their position to found a startup competitor. Toyota buys parts from many different vendors. A battery manufacturer, on the other hand, may supply batteries to Toyota, Ford, and BMW.

Complex systems function more like an ongoing dance, with the dancers changing partners on the fly. Schools of fish and flocks of birds offer compelling illustrations of complexity. A bird flying within a flock can position itself next to any other bird within that flock. It can change positions at will. It decides where to fly next in concert with the other birds that happen to be near it at any given time.

Emergence

Complex systems arise from nonlinear interactions between their components. That’s a fancy way of saying that the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. You can’t capture the behavior of the flock by examining the behavior of the individual birds. The beautiful, fascinating, mysterious ebb and flow of the flock represents a property of complexity known as emergence. Emergent characteristics exist at the system level without any direct representation at the level of individual components.

Birds fly according to three simple rules:

- Fly in the same general direction as your immediate neighbors.

- Fly toward the same general destination as your immediate neighbors.

- Don’t fly too close to your immediate neighbors.

A group of birds flying according to these rules will generate a pattern that we perceive as flocking. There is nothing in the rules, though, that directly explains that pattern. One might even say that the flock really only exists in our minds.

A complex system like a flock of birds might display emergent, coherent patterns. Those patterns, however, result from the behavior of components making individual, independent decisions. Each bird within a flock decides for itself how to respond to any given situation. A car whose doors could wander off and come back again would need a much more flexible definition of structural coherence. Otherwise it would quickly fall apart.

This difference in structural coherence illustrates a critical difference between complicated and complex systems. Complicated systems rely on centralized control and hardwired organizational structures. As a result, they work very efficiently until they break. The fact that the parts of a car all hang together is good for streamlining and thus fuel efficiency. If a wheel falls off, though, the entire car comes to a grinding halt.

By contrast, complex systems are sloppy and prone to component failure, yet highly resilient. Their decentralized, fluid structure trades efficiency for resilience. A flock of birds that encounters a giant oak tree happily splits apart and flies around it. The flock then glues itself back together again on the other side. A few birds might unfortunately fly into the tree. The flock as a whole, though, is unharmed by its encounter with a large obstacle. By contrast, an airplane that tried to split itself into pieces and fly around a similar obstacle would fall to the ground and crash.

Emergence presents both challenges and opportunities to organizations trying to manage complex socio-technical systems. On the one hand, it requires tolerance for failure and apparent inefficiency. On the other hand, it offers a decentralized, responsive, and scalable approach to achieving success, whether defined as control, quality, competitiveness, or profitability. Organizational methodologies that leverage the power of emergence can help companies achieve strategic coherency without sacrificing tactical flexibility.

Cascading Failures

At the same time that complex systems demonstrate resilience, though, they are also subject to the phenomenon of cascading failure. A cascading failure is one that occurs at a higher system level than an individual component. In a complex system, failures can also result from the interactions between components. System-level failures can even happen while all the individual parts are operating correctly.

Contemporary industrial safety research explores this phenomenon. It might be possible, for example, to extend the maintenance schedule for an airplane part without violating the acceptable wear tolerance for that part. Taken together with similar changes elsewhere within the system, however, that extension might tip the whole system into an unsafe state.

The potential for cascading failures challenges complicated-systems approaches to planning and quality assurance. Reductionist techniques that break systems into their parts are insufficient for modeling complexity. In order to understand each component and its potential to cause problems, its relationships with other components must also be considered.

Sensitivity to History

Finally, complex systems exhibit what’s known as sensitivity to history. Two similar systems with slightly different starting points might dramatically diverge from each other over time. This phenomenon is known as the butterfly effect. The butterfly effect describes the imagined impact that a butterfly flapping its wings has on weather patterns on the other side of the world. If the butterfly in Singapore does not fly away from a flower at precisely the time that it does, so the parable goes, a hurricane might not come into being in North Carolina.

In August 2013, the Nasdaq trading systems went offline for the better part of a day. The reasons for the outage present a fascinating example of cascading failure coupled with sensitivity to history. The “root cause” of the outage was unusually high incoming traffic from external automated trading systems. The rapidly accelerating traffic triggered a fail-safe within Nasdaq’s software systems that caused them to fail over to a backup system. That same traffic level triggered a bug in the backup systems that took them completely offline.

One might point the finger at the bug as the cause of the outage. Ironically, though, the problem started because of software doing exactly what it was supposed to do: fail over based on load. That failover was intended to function as a resilience mechanism. The outage also might never have happened had the morning’s traffic profile been just a little bit different. Had it not peaked quite as high as it did, or accelerated quite as quickly, the bug might not have been exposed and the failover might have worked perfectly. Or the failover logic might not have triggered at all, and the primary systems might have struggled successfully through the morning.

Emergence, cascading failure, and sensitivity to history conspire to make it infeasible to predict, model, or manage complex systems in the same ways as complicated systems. Trying to manage them too tightly using traditional top-down command-and-control techniques can backfire and turn resilient systems into brittle ones. The ability to survive, and even thrive, in the presence of failure is a hallmark of complex systems. Fires renew the health of forests. Attempts to prevent them often have the counterproductive effect of creating the conditions for catastrophic fires that destroy entire forests.

Instead, post-industrial organizations need to approach management with a newfound willingness to experiment. When prediction is infeasible, you must treat your predictions as guesses. The only way to validate guesses is through experimentation. Just as complex systems are rife with failure, so too are attempts to manage them. Experiments are as likely to return negative results as positive ones. Management for resilience requires a combination of curiosity, humility, and willingness to adapt that is unfamiliar and counterintuitive to the industrial managerial mindset.

Real-World Complexity

Complexity is more than just theoretically interesting. It increasingly presents itself in real-world business and technical scenarios. Employees have always communicated within corporations across and sometimes in flagrant disregard for formal organizational structures. In response to post-industrial challenges, businesses are trying to unleash innovation by encouraging rather than stifling complex-systems-style communication and collaboration. Management consultants are calling for the outright replacement of hierarchical corporate structures with ones that are flatter, more fluid, and more network-oriented.

The cloud is a prime example of complexity within the digital realm. A small business may run its finances using an online invoicing service from one company, an expense service from another, and a tax service from a third. Each of those companies may in turn leverage lower-level cloud services that are invisible to the end customer. If, for example, Amazon Web Services (AWS) has an outage, does the small business need to worry? The owners may not know that their invoicing service runs on top of Heroku’s Platform-as-a-Service (PaaS). Even if they do, they still might not know that Heroku runs on top of AWS.

Twenty-first-century workplace trends are fundamentally changing the relationship between companies and employees. So-called Bring Your Own Device (BYOD) means that employees own their own laptops and smartphones, and can mix personal and company data on the same devices. Telecommuting and coworking move physical workspaces out of companies’ control. Shadow IT lets employees buy and manage computing services without IT’s control or even knowledge. Finally, companies’ growing reliance on freelance labor changes the company–employee relationship at the most basic level.2

Together, these trends all contribute to transforming corporate environments from complicated to complex systems. They transform the management of people, devices, systems, and data from a closed hierarchy to an open network. Open organizational networks create new opportunities for business resilience, adaptability, and creativity. At the same time, though, they stress traditional management practices based on control and stability.

From Efficiency to Adaptability

Twentieth-century business structures epitomized the model of corporations as complicated systems. Companies flourished by growing in both size and structure. They mastered industrial-era technical and management practices that maximized efficiency and stability. They used these practices to create robust hierarchies that supported ever-increasing economies of scale.

Giant, long-lived companies like Ford, Johnson & Johnson, AT&T, IBM, and Kodak created and dominated entire product categories. They became known as blue-chip stocks with “a reputation for quality, reliability, and the ability to operate profitably in good times and bad.”

The twenty-first century features the arrival of disruption. Companies like Salesforce.com, Apple, and Tesla compete not by beating their rivals at their own game but by changing the game itself. Software-as-a-Service (SaaS) doesn’t just retool software for a service economy. It challenges the very relevancy of on-premise software. Why bear the cost or burden of installing and operating your own software when you can let a service provider do it for you? Why incur large up-front capital expenditures when you can pay on-demand service fees that ebb and flow with your business?

Smartphones with high-resolution, built-in cameras challenge the relevancy of the camera as a dedicated product. Why carry around a separate photo-taking device when you can use the one that’s already in your pocket? Why fumble around with SD cards to transfer your photos to a computer in order to edit and share it, when you can edit and upload directly from the device that took the picture in the first place? Kodak’s inability to adapt to the smartphone revolution doomed it to a rapid death after 100 years of operation.

Tesla doesn’t just compete with companies that produce internal combustion-engine cars. Those companies are also producing cars with electric engines. By focusing on the zero-maintenance nature of electric cars and selling them directly to customers, Tesla is challenging the very existence of physical sales-and-service dealerships. The car dealership industry is responding not by innovating their own practices but by lobbying state legislatures to forbid direct sales of automobiles from manufacturers to customers. This tactic represents the competitive strategy of the beleaguered.

Economic transitions are fecund opportunities for disruption. As we move from industrialism to post-industrialism, new companies are disrupting incumbents by better understanding and grabbing hold of the nature of service and digital infusion. Smartphones replace cameras not just because of their physical convenience but also because of their native integration with digital services in the cloud.

Cameras were invented during the era of physics and chemistry. They represented insights into the nature of light, glass, silver, and paper. Digital photography dispenses with negatives and prints in favor of pixels. By doing so, it integrates photography with the realms of content and social media. It dissolves the boundary between pointing a physical device at an interesting building and chatting with your friends back at home about your trip to Europe. Facebook believed in the power of infusing photography and social media enough to pay $1 billion for a mobile photo uploading application.

Toyota and Chevrolet approached electric cars as a matter of replacing drivetrains. Tesla, on the other hand, took the opportunity to reimagine the entire experience of owning and operating a car. Tesla’s challenge to the dealership model strikes at the heart of one of the most unsatisfying service experiences in modern life. Its cars are also deeply digitally infused. The onboard displays look more like an iPad than a traditional car dashboard. Tesla drivers can remotely open vents and lock and unlock the car using a mobile app.

In a testament to the “software is eating the world” meme, Tesla engineers its cars to work like software as much as hardware. The company provides APIs that allow third parties (including technically minded owners) to write their own applications. Tesla remotely updates its cars’ onboard computer systems the way one would a website. APIs and automated updates may not sound strange or unusual in this day and age until we remember it’s a car we’re talking about!

Facing Disruption

The pace of disruption is accelerating. Kodak was in business for over 100 years before being disrupted by digital cameras and smartphones. Microsoft went from a monopoly to an also-ran in the course of 20 years. In 2012, Nokia was the world’s largest cell phone manufacturer. In 2013, when Microsoft bought it, pundits wondered whether one irrelevant company was buying another. Apple went from the world’s most valuable company to a question mark—Is it being disrupted by Google? Is it being surpassed by Samsung? Has Apple lost its mojo?—in 12 months.

Disruption invokes what Clay Christensen called the innovator’s dilemma. Disruptive innovations address customer needs left unserved by incumbents. These needs are unserved precisely because doing so would be unprofitable given the existing business model. Incumbents are often paralyzed against responding to disruptive competition because they can’t get out from under their own feet.

In order to succeed in the age of disruption, companies must change their basic approach. They need to shift their emphasis from perpetuating stability to disrupting themselves. Instead of excelling at doing the same things better, faster, and cheaper, they need to challenge themselves to continually do different things, and continually do them differently. They need to learn to value learning over success, and to value the ability to change direction over the ability to maintain course. In other words, they need to shift their core competency from efficiency to adaptability.

Apple is the poster child for the growing sensitivity to disruption in the marketplace. Investors no longer judge Apple primarily by its revenues, profits, growth, or market share. They judge the company by what it’s done that’s new and different. Apple successfully transformed itself from a computer company to a mobile device company. Now, though, announcing a new, better, faster, bigger iPhone isn’t enough. Investors and pundits clamor for a TV, a phone, or even better, something that doesn’t have a name yet. The expectation isn’t that Apple will improve the next device it releases, but rather that it will redefine it the way it did the cellphone.

Brands as Digital Conversations

Post-industrialism impacts companies on every level. They must truly become digital businesses. They must transform not just how they operate or organize themselves but also how they conceive of themselves. The post-industrial worldview must inform everything they do, from their most basic daily processes all the way up to the way they perceive themselves and behave as brands.

A brand represents “the unique story that consumers recall when they think of you.”3 That story reflects the promises you’ve made to your customers and the extent to which you’ve kept or broken them. These promises involve commitments to help customers and can operate on multiple levels. A sneaker company might promise to keep your feet comfortable while you run but also to help you look cool. A car company might promise to help you drive safely, but also to maintain your social status.

Companies devote tremendous energy to creating and maintaining their brands. The post-industrial economy makes brand maintenance significantly more challenging. Service transforms it from a vendor-driven activity into a conversation with the customer. Service providers must make promises about listening and responding as much as making and delivering. I judge my car company as much by its service department as by the quality of the car itself. I also judge its ability to improve its products and services over time.

Digital infusion moves the brand conversation firmly into the digital realm. I’ve reached the point where 99% of my relationship with my bank happens via its website. My impression of the bank’s brand derives directly from the quality of its online presence. If the website is slow, clumsy looking, and hard to use, those characteristics will define the story I recall when I think of it. By making its site faster, better looking, and easier to use, the bank improves not just the quality of its online service but also the quality of its brand.

Complexity challenges companies’ ability to control their brand promises. When failure is inevitable, broken promises also become inevitable. Brand maintenance thus must incorporate the ability to repair promises in addition to keeping them in the first place. The way in which companies respond to events such as security breaches become critical brand quality moments.

Companies must do more than just keep their promises. They also must make the right promises. Promising speed and handling when people value fuel economy as much as performance could degrade rather than enhance a car company’s brand. Disruption complicates brand maintenance by changing the landscape under companies’ feet. Tesla, for example, is disrupting the meaning of brand in the automobile industry by combining performance, luxury, and environmental sensitivity.

The post-industrial economy dissolves any remaining separation between branding and conducting business. Social media contributes to this trend by wresting control of a company’s brand away from it in favor of consumers. No longer does the company drive the public’s impression of it. Instead, companies become mere participants in the discourse about their identity, quality, and value.

Post-industrialism turns brand management into a digital conversation between a company and its customers. Brand quality depends on a company’s ability to conduct that conversation as seamlessly and empathically as possible. Having lost control of the message, companies must shift their focus from trying to shape their customers’ perceptions, needs, and desires, to accurately understanding and responding to them. The capacity for empathic digital conversation thus becomes the defining characteristic of post-industrial business. The ability to power the digital brand conversation in turn becomes the defining measure of quality for post-industrial IT.

The New Business Imperative

In order to shift their approach to brand management from a broadcast model to a conversational model, twenty-first-century businesses must simultaneously transform the way they relate with their customers and the way they organize their internal operations. Conversation depends on the ability to listen and to respond appropriately to what you’ve heard. Digital businesses thus must organize themselves to accurately, continuously process market and customer feedback.

The ability to process feedback fluidly is a critical component of post-industrial business success. Service requires conversational marketing and co-creative business operations. Infusion requires deep integration between technical and business concerns across physical and virtual dimensions. Complexity requires exploration and tolerance for failure. Disruption requires an unfettered ability to uncover and pursue new possibilities.

These requirements necessitate an internal transformation that mirrors the external one. In order to provide high-quality, digitally infused service, the entire delivery organization must function as an integrated whole. In order to handle the perturbations caused by complexity and disruption, that same organization must be able to flex and adapt. The post-industrial company thus begins to look more like an organism and less like a machine.

Post-industrial businesses are beginning to experiment with nontraditional organizational structures. Dave Gray has described networks of pods in his book, The Connected Company. Zappos, an online shoe retailer, is experimenting with holacratic management structures that distribute decision-making throughout self-organizing teams. Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos coined the phrase “two-pizza team” to refer to small, integrated teams that have the autonomy and intimacy necessary to move quickly (and can be fed by just two pizzas). Yammer, an enterprise collaboration software vendor purchased by Microsoft in 2012, dynamically creates similarly sized functional teams. Each team dissolves and reorganizes after every project in order to propagate knowledge throughout the larger organization.

These new structures leverage the power of emergence to balance flexibility with coherency. In order to use them successfully, however, twenty-first-century businesses need more than a new org chart. They need a new worldview from which to operate, one that shifts the emphasis of management values, goals, and structures, and the IT systems that support them:

- From efficiency, scale, and stability to speed, flexibility, and nimbleness

- From discontinuous broadcast to continuous conversation

- From avoiding failure to absorbing it

- From success as accomplishment to success as learning