An efficient approach to continuous documentation

How to cultivate lasting shared knowledge without giving up all that free time you don't really have.

Paper (source: Egle_pe)

Paper (source: Egle_pe)

An outside observer watching a software developer work on a small feature in a real project would find the process to look less like engineering and more like a contrived scavenger hunt for knowledge new and old.

The problem is that we scatter what we learn and teach to the winds. A quick comment on a pull request transfers knowledge from one head to another, but then falls off the radar. A blog post covers some lesson learned while working on a project, but then never gets touched again after it’s written. A StackOverflow link is passed through Slack, and then disappears into the back scroll.

We can do better. In this article, I will explain how to get started on a more systematic way of cultivating knowledge. It’s something that won’t take you more than a few minutes a day at first, but it’ll pay off in massive volumes.

Begin by keeping a journal of field notes

The path towards one day having a comprehensive internal knowledge base begins with a baby step: updating a journal at least once daily with some notes about your work.

Start with nothing more than a single blank text file. You can use plain text, markdown, or any other format you’d like… but be sure to use something you won’t fiddle with, so that you can dump raw notes with as little friction as possible.

What should you capture in your journal? Pretty much anything and everything related to your experiences at work.

Don’t try to come up with a way to categorize things at first, and don’t attempt to come up with a standard prompt or template for each entry. Some notes might be two lines long, some might be five pages. Some entries might be undocumented snippets of code you copy-and-pasted, some might be diary-like reflections.

Expect your work journal to cover a wide range of topics; some very technical, some less so. If you’ve never done this sort of writing before, here are a few sample notes just to give you some ideas:

- “Every time our monitoring system kicks up alerts, Nasir is the only one who can troubleshoot them and resolve the issues. There are also frequent false alarms. This happens several times per week and is frustrating our customers.”

- “Today I read about a new library that seems like it could be useful for generating PDFs in our inventory management system project.”

- “Every time I touch the part of this old codebase which handles payment processing it’s terrifying! There are no tests and very little documentation, and the person who originally wrote it left years ago.”

Each of these notes could be captured in seconds, at the moment the thought came up. More detail can always be added later, but that’s strictly optional. Whatever you do, make it so that your daily journaling is easy enough that you stick with it, even if it means writing only a tiny bit each day.

After a few weeks, review your notes and look for recurring themes

Once you’ve collected a couple dozen entries, skim through your journal and write a one line summary of what each one is about, and then review the resulting table of contents. Doing this is unlikely to yield a complete set of categories that you could group your entries by, but I’d be surprised if you couldn’t discover a few common threads this way.

Create a new document for each of the themes you’ve identified, and then spend a few moments summarizing the more interesting parts of your journal related to that theme. Below that summary, add a TODO section and then brain dump anything you’d like to write more about or study more related to the theme, but haven’t found time for yet.

At this point in the process, all of your notes are just for your own sake. You might reference them when talking with someone else on your team or when preparing some more formal learning materials, but they’re not “documentation” yet… they’re raw materials.

After you complete this initial review, keep doing daily journal entries… and don’t feel pressured to categorize them as you write. But every couple weeks, review your entries and keep building out your themed summary documents.

Your summarized notes will start to become more structured, because you’ll be intentionally looking for common threads during each review. Once that happens, it’s a sign that you’re ready to start building out a formal knowledge base.

Fair warning: It may take months to reach this point, and that’s absolutely fine. If you rush ahead too quickly, you’ll inevitably hit all the dead ends and headaches that make it so that people don’t spend much time on documentation in the first place. Patience is a virtue.

Bootstrap your way towards continuous documentation

By the time you reach this point of the knowledge cultivation journey, you already have a repeatable process for capturing the things you think about and struggle with day-to-day, as well as a system for categorizing and summarizing those thoughts into more structured notes. You also will have developed a habit of treating writing as something that’s just part of what you do in the ordinary course of a day’s work, rather than an isolated and even somewhat scary activity.

The problem is that all those lovely notes you wrote will eventually collect dust if you don’t find a way to systematize things further. This is where a wiki or some other form of content management system starts to become a practical requirement.

It’s important to not overthink this part: pick the least powerful (and/or least distracting) tool that you can find that lets you publish documents that are easy to edit, and easy to link together.

Do not… I repeat…. do not… attempt to roll your own tool at this early stage in the game. You will inevitably start solving the wrong problem that way, and it’ll become a massive time sink that will leave you lost out in the weeds.

From here, the next step is to seed your knowledge base with the themed sets of notes you have been developing over the last several months. Build out stub pages, and clean things up a bit. Create a few index pages and link related documents together. The ultimate goal is to make this new system at least somewhat comprehensible to other human beings, so that they can begin contributing to it as well.

What kinds of pages will end up in your knowledge base? Like your journal of field notes, you can expect an impossibly broad spectrum ranging from “how to answer a support phone call” to “which authentication strategy should I use?”–in other words, it’ll be a huge mess at first and it will annoy you.

The only solution I’ve found to this problem is to use internal documentation constantly. Make it the first place you go when looking something up, rather than searching the web or asking a coworker.

Pretend as if you expect things to go smoothly for the first 30 seconds or so… and then when you inevitably hit a rough edge or a missing link, take another 30 seconds to write down what went wrong in a wish list for future improvements, or drop a FIXME note right where you spotted a problem. Then without any sense of guilt, immediately revert back to your old way of doing things for the moment.

Whenever you find a bit of downtime, go through and fix problems in your knowledge base. As Stephen Pressfield says in one of his books, “Fill in the gaps; then fill in the gaps between the gaps”

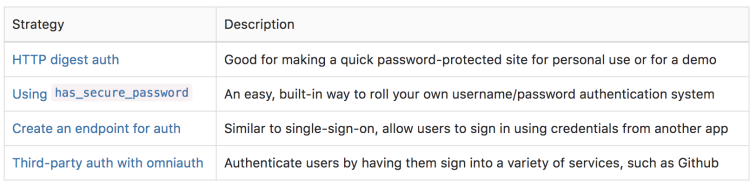

For example, turn a FIXME note at the top of an authentication strategies document that has gotten massive and difficult to skim into a table listing why you’d want to read the content in each of its sections, with links straight to those sections:

Or if you have more time, research and write up docs for something that has been sitting on your wish list for much too long. If you only get halfway through something and need to stop, no problem. Drop a bunch of TODOs right in the document, and deal with them next time. Get in the habit of seeking out and enjoying small wins.

Finally, remember that knowledge development is an infinite game

If you follow the process I’ve described in this article for a year, you will end up with a very useful knowledge base, but it’ll be nowhere close to done. You also will not have come anywhere close to finding the right way of organizing things–if anything that problem will become more and more challenging over time.

But the path you’ll be traveling is an upward spiral, not a circle. Initially, the bulk of your time will be spent documenting tedious things like what version of Library X is compatible with Library Y, or how to interpret each of the 36 different kinds of errors that your exception reporting system routinely kicks up in a given month. But as soon as those topics are well covered, the time once spent on muddling through these issues gets reclaimed.

With the time you free up, you’ll begin to chase down more substantial topics: things like architectural patterns that you’ve found useful across a wide range of projects, or usability guidelines for business reporting, or how to use budgeting as a project planning tool.

That said, whenever you enter a new area that is outside of the documented set of core technical skills… it’ll feel like you’re back at the beginning again. But little by little, you’ll fill in those gaps, and the gaps between the gaps, and then you and your team will end up stronger for it.

I’d like to thank Hunter Stevens, who helped me design this documentation process as she worked through an apprenticeship program with me over the last year.