10 principles of business transformation

To become a high-performance organization, you must develop the capability to continually adapt, adjust, and innovate.

Roman numeral 10. (source: Pixabay)

Roman numeral 10. (source: Pixabay)

Transforming organizations, teams, or even yourself is challenging. There’s no one-size fits all method to achieve success. It’s a combination of hard work, persistence, and patience.

The most successful enterprises are continually experimenting to learn what works and what doesn’t. They focus on meeting customer needs by clarifying goals, shortening feedback loops, and measuring performance based on outcomes, rather than outputs.

To become a high-performance organization, you must develop the capability to continually adapt, adjust, and innovate. This requires a deliberate practice of experimentation and learning.

But experimentation alone is not the answer. To enable and empower decision-making at scale, team members need a framework of reference to align their actions to the organization’s mission. The mission is the statement of purpose for what your organization stands for. The principles help individuals and teams make independent decisions at speed that are aligned to the organization’s mission, valued behaviours, and desired culture. It is not a set of explicit rules or command-and-control statements of how people should operate.

Based on my own experiences I’ve distilled a set of 10 principles to transform to help businesses on their journey to become high-performance organizations.

Think BIG, learn fast, start now

Every great mission needs a compelling and aspirational vision. The clarity with which you communicate the vision gives people purpose, direction, and constraints as to why the initiative they are taking part in matters. Thinking BIG means challenging assumptions of what we believe may even be possible.

For example, thinking BIG at SpaceX is: “SpaceX designs, manufactures and launches advanced rockets and spacecraft. The company was founded in 2002 to revolutionize space technology, with the ultimate goal of enabling people to live on other planets.”

However, a vision is a theory, a set of beliefs and untested hypotheses that must rumble with reality.

In the information age, the organization that can most effectively accumulate new knowledge and leverage that insight to make better decisions wins. Organizations with the highest quality information make the best quality decisions. To accumulate new knowledge, we must experiment. By experimenting, we learn. Whoever learns the fastest wins.

Be uncompromising with the BIG vision, but develop methods to learn fast what works and what doesn’t. Start testing the BIG idea with real customers and users as quickly as possible—even when it’s feels early and uncomfortable.

Secure mandate, sponsorship, and support

You will only be as successful as the level of leadership in your organization that gets behind the initiative. If there’s no support in the team, the leadership or executive group, then forget it. That said, making innovation only the CEO’s job isn’t going to cut it either.

If you want to be a leader of change, it’s your responsibility to create the space, support, and sponsorship to enable experimentation to happen.

Do this by focus on outcomes, not outputs. Define constraints, limit investment, or risk thresholds to create safe-to-fail experiments. This creates a sandbox for learning and will result in demonstrable evidence of progress. It allows teams to explore uncertainty within the bounds of recoverable situations, reducing learning anxiety and paralysis from the fear of failure.

“If the highest aim of a captain were to preserve the ship, they would keep it in port forever.”–Thomas Aquinas

Right people in the right place

Putting change-averse people into a high-change environment won’t break the system; it will break the people.

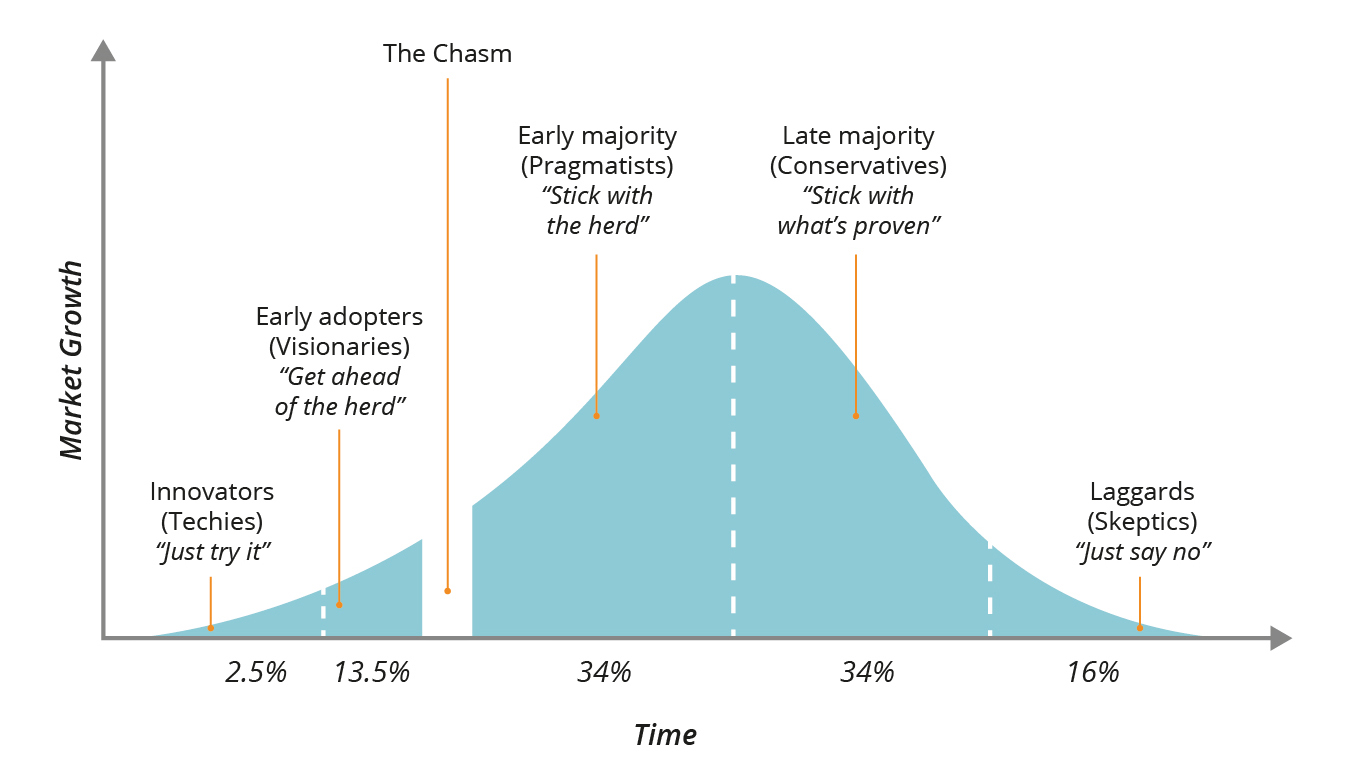

Similar to Geoffrey Moore’s model for technology adoption, there are all types of mindsets in an organization toward change, from innovators to laggards.

Be aware of people’s natural bias when it comes to building teams capable of dealing with extreme uncertainty and frequent iteration. High-performance teams start small with a cross-functional representation of business, technology, and design. This is the nucleus to build a team around. Be deliberate about how you form the team and the type of work—be it highly exploratory or otherwise—they focus on.

Act your way to a new culture

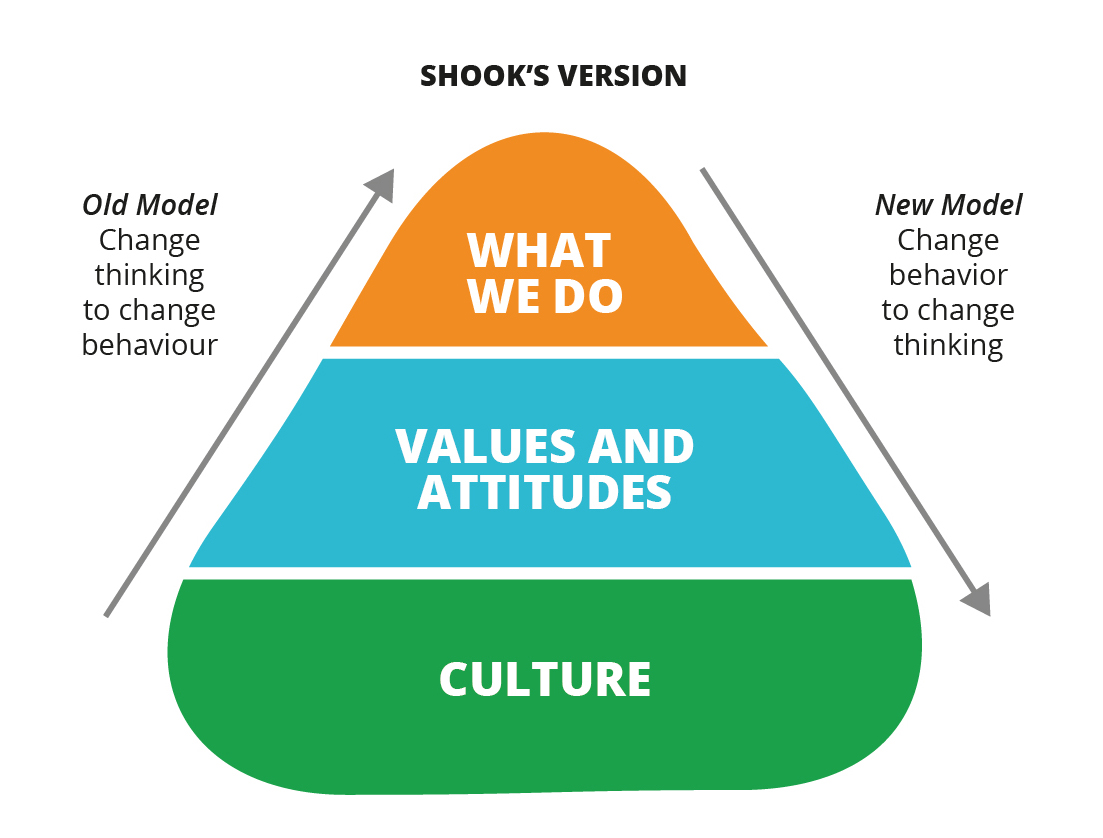

John Shook was the first American to be hired by Toyota. He moved to Japan in the mid-70s without knowing a single word of Japanese, only a curiosity to learn about the Toyota Production System. What he observed contradicted everything he had seen and heard in Western organizations. The Western belief was if you told people to think differently they would suddenly act differently.

What Shook actually experienced at Toyota was that changing the system of work is what led to a change in the way people behaved. People didn’t think their way to a new culture; they acted their way to a new culture. This is what SCRUM, XP, and many other agile methodologies actually try to enforce—a change in the system of work using iteration, ceremonies, reflection, and cross-functional teams to change how people interact and ultimately behave.

Sadly, many organizations still believe that sending staff on a one- or two-day certification course can suddenly make them agile, adaptive, and aware. Often, the result is people blindly following a methodology of what to do without ever understanding why they are doing actually it.

Build the right thing, then build it the right way

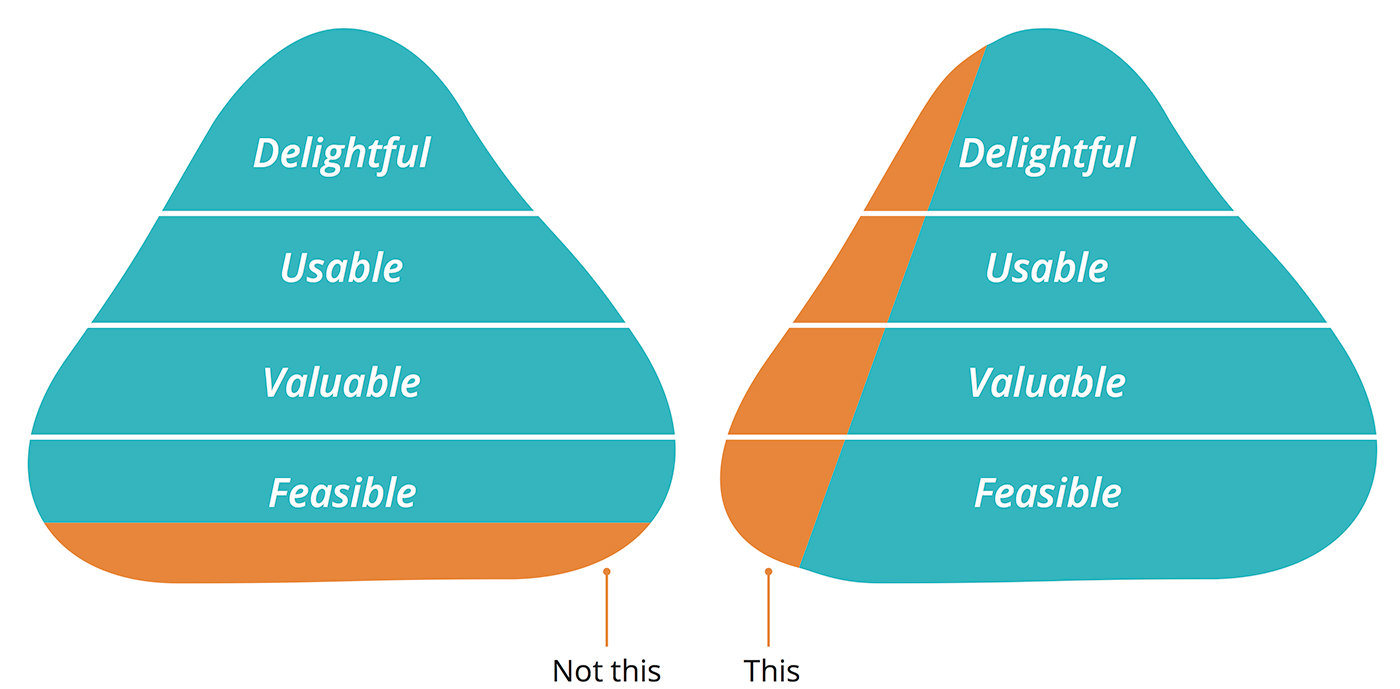

Working software is an experiment, just a really expensive one.

Unfortunately building the entire solution and only then testing it with customers is still the prevailing model of operation for most organizations.

One of the key components of the Lean Startup movement championed by Eric Ries is to encourage teams to test their business hypothesis as quickly and cheaply as possible. This is achieved by creating a Minimum Viable Product (MVP)—a basic early working example, prototype or experiment to test the area of greatest uncertainty related to the hypothesis.

A MVP approach enables you to fail fast and cheaply, while also gathering valuable data from the experiment. As you prove or reject different hypotheses, you build confidence that the problem/solution fit is on the desired path. You can then invest more to improve the fidelity of the solution, widen the marketing reach and/or enhancing the solution based on the data gathered—essentially increasing your exposure to risk in a controlled manner.

Deliver small, fast, and frequently to build momentum

One of the most important aspects of agile and lean methodologies is working in small batches. Reducing the size of work batches enables us to optimize for end-to-end throughput of our system of work. This allows use to gather data against the outcomes we achieve and compare them to our initial expectations of success.

Secondly, the data we collect becomes inputs for reflection, decision-making and adapting strategies. How are we moving toward the desired outcome? Should we adapt the objective of our original mission? It’s how doing and learning enables better top-level decision making, not just in the execution of a given solution. The longer we wait to collect data to inform our next steps—especially when operating in extreme uncertainty—the higher the level of risk we are exposed to.

The best way to build trust with stakeholders is with frequent demonstrable progress. Showcasing small, completed pieces of work fast and frequently creates feedback mechanisms, trust and belief that team members can deliver.

Teamwork is about trust. Trust is about believing in your team members to deliver. You create belief with frequent demonstration of progress

— Barry O’Reilly (@barryoreilly) March 30, 2016

Build in feedback loops with customers and users

Customer testing should be for breakfast, not dessert. If you’re not testing with customers as soon as possible to understand if their problem really exists and that your solution addresses it, then you’re wasting valuable time, effort and resources.

The best people to provide feedback on your hypothesis are real customers—not your boss, or colleagues, or even team members. Regular and direct customer feedback is your guide towards fit, purpose and success. Make sure you design a system of work that gives the team frequent opportunities to test and incorporate customer and user feedback.

Following a recent ExecCamp, one of the participating executives sent me the following note:

“One of the team came to me today to ask to review the new designs for a system we’ve been developing. After ExecCamp the response was obvious to me… “I’m not the person you need to be testing with. The real people you need to talk to is our customers. Go find a few of them and get their feedback for what works and what doesn’t.”

Adapt your approach based on validated learning

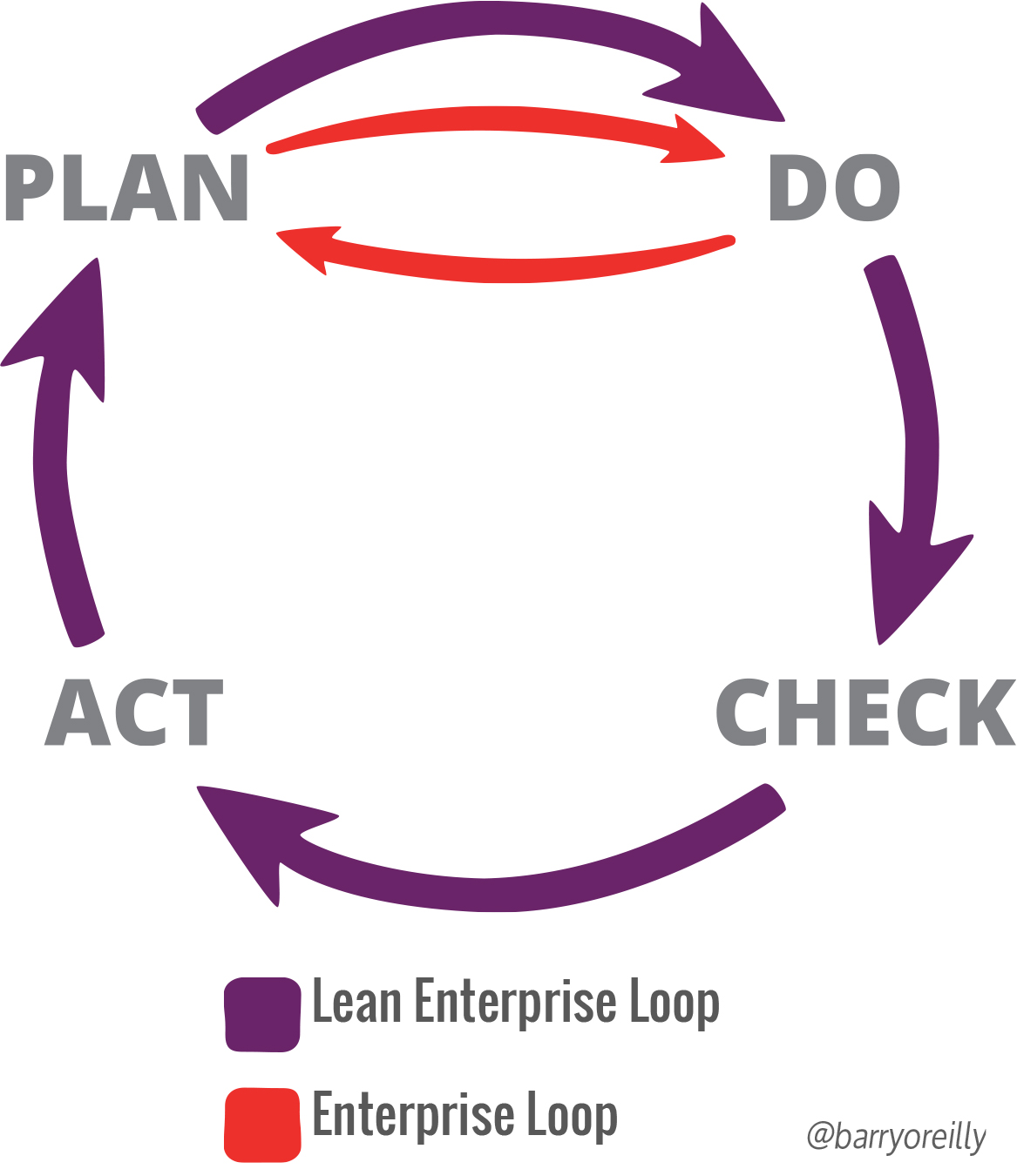

Lean and agile aren’t just about experiments to create new knowledge, they’re about using that knowledge to make better and more informed decisions on what to do next.

Many experiments will ‘fail’, but even these will result in validated learning. Validated learning means that we test—to the necessary degree of precision and no further—the key assumptions behind the hypothesis to understand whether or not it will succeed, and then make the decision to persevere, pivot, or stop.

By defining and communicating what success looks like before we start we create an accountability loops to decide if and when our initiatives are getting traction based the outcomes achieved.

Organizations that fail to define success before experimenting get caught in Plan->Do cycles, only validating outputs. Their success is on time, on budget, on scope without any learning mechanism to ask the questions; Did we achieve the outcome we expected? Are we getting better?

Demonstrate evidence for future investment decisions

Writing a well-crafted business case may secure initial funding, but it has little impact on whether your initiative actually succeeds or fails. As Douglas Hubbard documented in his book How to Measure Anything, the two biggest risks to any new initiative are not how much it costs and when will we deliver it but reducing the concern that the initiative will get cancelled and will our customers or anyone use it?

What’s important when making investment decisions is to take an evidence-based approach to ongoing funding by creating an evaluation framework to manage and prioritise future investments.

The cadence of iteration and review should match the level of uncertainty. For example, in financial markets traders get continuous and virtually real-time feedback on how the market is adapting in order to make further investment decisions and improve their probability of success. In contrast, an organization with an annual planning cycle and quarterly review process has only four iterations or feedback loops a year. In my experience, when working in a highly complex and adaptive environment four learning cycles per year is rarely sufficient.

You can minimize risk, uncover options, and get the best return on your efforts by using techniques such as customer testing, pre-defining measures of success and setting investment boundaries around time, effort and scope. This builds in regular feedback loops for course correction or close.

As I’ve said previously in blogs and talks on agility in financial management— It’s time to blow up the business case.

Scale lessons learned to cross the chasm

Scaling agile practices or frameworks doesn’t work—scaling learning does.

Teams learn best from the lessons of their peers. What challenges did they face? How did they address them? What would they do differently?

People remember stories and take inspiration from the experiences of others. Start by encouraging teams to showcase their experiments, discoveries and next steps. Make it easier for everyone to learn from one another, build momentum and drive change.

As a leader, your responsibility is to enable organizational learning by reducing collaboration friction between teams and designing systems of work with in-built learning mechanisms. The purpose of a learning organization is to help others make better mistakes, not the same mistakes.

Thanks to Qiu Yi Khut and Jonny Schneider for their feedback on initial drafts.