Chapter 4. Industry Context

You can’t just ask customers what they want and then try to give that to them. By the time you get it built, they’ll want something new.

Steve Jobs

In this chapter, we review three patterns useful in understanding the industry that your company operates in:

SWOT

Porter’s Five Forces

Ansoff Growth Matrix

Even if you have not been explicitly asked to perform an industry analysis and are only making a local architecture, I encourage you to quickly consider your project through these lenses, as they will improve your design’s extensibility and fitness to purpose.

SWOT

You may have used a SWOT analysis. Because they’re simpler and quicker to create than other patterns in this book, they are more popularly known. We can cover this quickly.

SWOT is an acronym for Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats. It gives you a view of these in a single slide.

You can conduct a SWOT analysis in three easy steps:

-

Conduct interviews with people at different levels in the organization and in different departments and roles. Ask them what they think your strengths are as an organization; what gives you competitive advantage; what people, process, and technology you have that makes a difference and helps you win in the market. Then ask them what your weaknesses are in people, process, and technology within the organization. Ask them what they see as new, different, innovative things the organization could be doing and where there is an underserved market, stubborn competitor that perhaps you could topple, or similar business you can serve.

-

Record their responses in a list organized into those four categories, with tags for “internal” (forces within your organization), and “external” (forces outside your organization). Reduce the list into the most important elements, removing duplicates and overly anecdotal or biased items.

-

Transfer the lists into a slide that looks like Figure 4-1.

Figure 4-1. Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats

These ideas are organized through two lenses, or across two axes: placement and potential. Placement is either inside your company or outside it. Potential refers to whether it’s harmful or helpful.

- Strengths

- Weaknesses

- Opportunities

-

These are external things that can potentially help you if you can figure out how to prioritize and take advantage of them.

- Threats

-

These are external things that you can’t control and must survey, understand, and determine how to shore up a defense for.

You can exercise the most control over internal things, so these are generally good places to start. Getting your own house in order is frequently easier and far more beneficial than always eyeing the competition and praying it doesn’t rain.

The SWOT can become part of your overall Strategy Deck to communicate with executives, and is most useful as material to focus and provide drivers for your architecture decisions.

Recall you can apply this and many other patterns in a variety of situations:

-

As a new person in an organization, you can do a SWOT analysis less formally and for your own understanding of the business, and to help you know where to focus.

-

When you’re creating an evolution of a legacy system, SWOT can help you plan the architecture and the accompanying product.

-

You can use SWOT when creating a departmental strategy.

-

When planning partner business updates or key customer meetings or large customer pursuits, SWOT can help you plan selling points, key differentiators, and responses to complaints and concerns.

-

SWOT analysis can help you create a long-term broad-based technology strategy across your whole organization.

Porter’s Five Forces

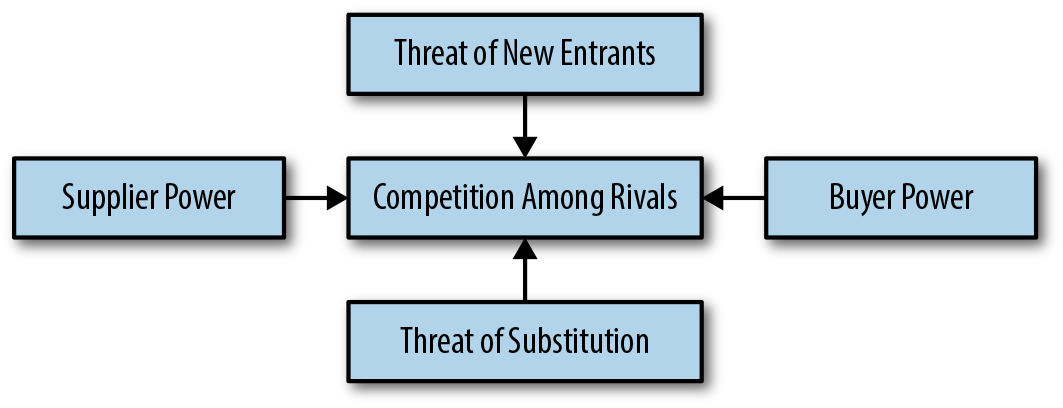

Michael Porter attended Princeton and then Harvard, and is a professor in Harvard’s School of Business. He founded The Monitor Group, which was later sold to Deloitte. He is widely considered one of the most prominent thinkers in the theory of management. He developed the Five Forces model in 1980 to help companies understand the different kinds of pressures that bear down on business so they can create and maintain competitive advantage. The forces he identifies are shown in Figure 4-2.

Figure 4-2. Michael Porter’s Five Forces

Let’s review each force.

Threat of New Entrants

This is the set of risks presented by new competitors entering your market. Google entered the search market in 1998, upsetting the then-dominant Yahoo! Amazon entered the brick-and-mortar retail grocery market with its acquisition of Whole Foods, creating a challenge for Sprouts and similar outlets.

The most attractive market segment is one in which entry barriers are high and exit barriers are low. High barriers to entry also tend to make exit more difficult. The airline industry has an incredibly high barrier to entry, since by definition you need to buy or otherwise have access to an airplane to fly people around in, you’ve got to get a variety of deals to land those planes at many airports, and there are serious regulatory hurdles to contend with.

You may have assets of your own in the form of patents and rights that can prevent others from entering your market. But beware of relying too heavily on this. The New York City taxi companies had a barrier to new entrants in the form of expensive medallions issued by the Taxi and Limousine Commissions. The gig economy upended this.

There are several other factors to consider:

-

Switching cost: how hard is it for your customers to leave your service and use a competitor’s?

-

Access to key distribution channels

-

Government polices and regulations

-

Capital requirements and total costs

-

Economies of scale that can be realized

-

Product differentiation

-

Customer loyalty to established brands and brand equity

-

Industry profitability

You can see how nearly all of these factors work against the airline industry, as an example. If an industry has high margins, such as the software industry, it becomes attractive to startups.

Ease of Substitution

A substitute product uses a different technology to try to solve the same economic need. Examples include meat, poultry, fish, and tofu, which can substitute for one another. Many landlines have been substituted with cell phones. This one is interesting because it seems like they’re both phones. But the threat came from outside the traditional phone industry—Apple wasn’t in the landline business and made a better landline that people switched to. So ask yourself how easy it is and what the main candidates would be for someone to stop using your product because of a substitution.

Factors to consider include:

-

Perceived level of product differentiation.

-

Number of substitute products available in the market.

-

Availability of close substitute. The Netflix engineering teams foregrounded the creation of APIs, as did Amazon, to make their products more ubiquitous and easy to access, and to mitigate against new devices or channels that could give audiences different content.

-

The general propensity to substitute. If you sell enterprise accounting or resource planning software systems, the propensity of middle-aged executives to change their multimillion-dollar operational software is typically low. Teenagers, on the other hand, eagerly search out substitutes for any current fashion or means of social connection.

-

Relative price of the substitute (consider the Canon and Xerox example in Chapter 1).

-

Switching costs buyers will incur.

Far fewer people buy desktop computers than did 10 and 20 years ago due to the advent of the powerful laptop, the smartphone, and a variety of internet-connected devices.

Bargaining Power of Customers

How much power do your customers have in the relationship? What is the degree to which they can influence or dramatically change your business? Factors include:

-

Degree of dependency upon existing distribution channels, and number of available alternative channels

-

How differentiated the products in the space are

-

Bargaining leverage, particularly in industries with high fixed costs

-

Buyer switching costs

-

Buyer information availability and customer education on the products

-

Availability of existing substitute products

-

Buyer price sensitivity

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Suppliers are the organizations that provide your company with the raw materials, components, labor, and services so that you can create your product. Suppliers can wield considerable power, depending on the dynamics of the industry, particularly where there are few substitutes, and the resources or talents are unique.

In the software business, there are really two primary suppliers. You need storage and compute (some kind of data center) and you need software developers. Your “supply” in this case is people. You can hire them, grow them as interns, get a bunch at once through an acquisition, outsource, hire agencies, and use consultants. Currently, much AI work requires PhDs in math or computer science, and the supply falls far short of the demand across not only the software industry, but all industries as they seek further automation and competitive advantage. As a result, they command incredibly high salaries, and can pick from an array of potential employers. As suppliers, these developers wield considerable power.

Factors to consider include:

-

Employee solidarity and labor unions

-

Level of differentiation between alternate sources

-

Impact of inputs on cost and differentiation

-

Potential substitutes

-

Strength of distribution channel

-

Ratio of supplier concentration to firm concentration

-

Supplier options to serve other companies

The software industry doesn’t really have labor unions. But in California, anyone with the job title of “engineer” is required to make a state-governed minimum salary. Of course, many firms pay higher than this, but it is a form of supplier power.

Related to differentiation levels across sources is the idea of the “10X programmer”—the special talent so skilled and knowledgeable that they can do the work of 10 regular programmers. Whether such a unicorn really exists at such a level is perhaps debatable, but it is crystal clear that not all programmers are created equally, any more than all basketball players are created equally. The more your technology stack is a commodity, the less differentiation there will be.

Consider the following talent life cycle.

In an emerging technology, where there are innovations springing up and relatively few pioneers on the planet who have even done this cutting-edge thing, and others in the same industry have yet to even hear of it, there is incredible talent differentiation.

Eventually word gets out, people get excited, and the clever people start learning this new technology and how to apply it. There is still considerable differentiation, but mostly because while the supplier pool has grown, there is a wide gap between “I’ve done it before” and “I just heard of it.” There are still precious few experienced practitioners, there is fierce competition to attract them, they do their own startups, and they command high salaries.

If there’s enough application and profit in it, eventually many technologists arrive on the scene, companies arise to teach it, and innovators profit by making it accessible to less schooled and less experienced practitioners. The sillier startups start failing, the hype cycle settles, and people see the tech’s true utility and where to apply it.

Eventually, however, when the tech becomes very widespread, it becomes like a commodity relative to its use value, where there is precious little differentiation. The price for this talent goes way down, and it becomes rather easy for employers to substitute one developer for another. This is where, say, Java is today: high demand, but everyone’s sort of just expected to know it and there’s little wringing of hands in executive suites about whether they’ll be able to find Java talent.

Then the tech becomes all but entirely automated away. People used to have whole jobs where they only had to type HTML because the web seemed like magic. Now only robots make HTML; it’s not a job for people anymore.

Industry Rivalry

Industry rivalry is about how the public perceives a product and distinguishes it from that of the competitors. A business must be aware of its competitors’ marketing strategy and pricing and also be reactive to any changes made. Considerations here include:

-

Sustainable competitive advantage through innovation

-

Powerful competitive strategy

-

Competition between online and offline companies

-

Level of advertising expense

-

Firm concentration ratio

-

Degree of transparency

Applying the Five Forces

Using the Five Forces is about thinking of your company in a holistic way and doing the research—getting the data—to create insights about what’s happening to your company.

This is a very powerful tool for the technologist. That’s because while every businessperson knows about Porter’s Five Forces, their familiarity with it may mean that it isn’t written down in a formal way. If it is, and you can access it, fantastic. But what I’ve mostly seen is that this is the very job of the business folks—to know these things, keep them in their heads, and make decisions accordingly. So, in addition to helping you learn about your business, ask smart questions, and instigate interesting conversations among your peers, you’ve got another reason to use the Five Forces. The business folks who have to do this kind of analysis quickly and in their heads, and just maintain the knowledge and make slight adjustments to their outlooks as they read headlines, have likely not seen the business from your perspective, through the lens of technology. Prepare your thoughts with this framework specifically in terms of how it applies to your technology, your software product portfolio, and your organization.

Here are four easy steps for putting the Five Forces to work:

-

In your scrapbook deck, or your burgeoning Ghost Deck (see “Ghost Deck”), for your strategy work, make a slide for each force, and list how, in your view, the company is positioned within it.

-

Make your claim regarding how an aspect of your proposed technology solution or direction supports or defends against each force. How do these circumstances change what you had previously thought your technology strategy should be? How do they expand it?

-

Tag each threat with a traffic light: state in red, yellow, and green if the threat seems high, medium, or low.

-

In a conclusion slide, make succinct recommendations regarding how you as a technologist think you can best position against each force.

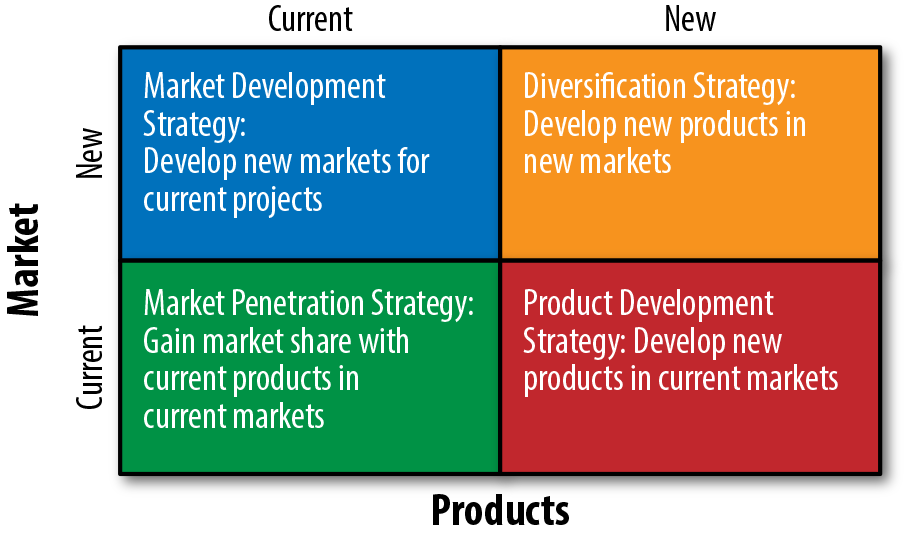

Ansoff Growth Matrix

The Ansoff Growth Matrix (AGM) was first published in the Harvard Business Review in 1957 by H. Igor Ansoff. In his article “Strategies for Diversification,” Ansoff illuminated the need for product managers, marketers, and executives to think about the potential avenues and risks of growth, and gave us a rule-of-thumb type of guide for so doing.

The Ansoff Growth Matrix looks like Figure 4-3.

Figure 4-3. The Ansoff Growth Matrix

It’s about four different ways you can grow the business. Here’s how to read it:

- Market penetration strategy

-

In the bottom left is the set of products that you have currently and the current markets in which they’re selling. With these products, you’re trying as a product manager to figure out how to gain market share. This is the easiest avenue, since you have confidence in your existing products and can build on word of mouth to get more customers like the kind. Can you acquire a competing company in the same field to gain more customers like the kind you already have? Can you introduce a loyalty scheme or otherwise create some stickiness? How do you ramp up your sales force?

- Market development strategy

-

Moving up, develop new markets to sell your existing products in. This means that you don’t necessarily have to change the products but instead sell them to a different kind of customer as a substitute for existing products in those markets, or begin selling in new countries, which may mean you have to adapt them. This is what Canon did when it figured out how to make copiers priced low enough that the company could sell to individuals and small businesses, who were previously neglected. The menu items and labels and even the names of products sometimes need to change. You may have to consider what additional special features to offer to cater to the new market.

- Product development strategy

-

Create new products in current markets. Can you create additions to your technology, building a platform or ecosystem? Amazon Web Services, for example, frequently adds new capabilities to extend the product set it offers to the same set of customers.

- Diversification strategy

-

Develop new products in new markets. This is quite risky and expensive. The benefit to considering diversification, just as in your personal financial portfolio, is that you minimize any negative impacts in changing tides.

The AGM will likely be one of the more distant models for you as a technology strategist, so I won’t belabor it further, but it’s good to realize that your product counterparts and marketers may be thinking this way, and you can understand your portfolio better through such a lens.

As with many of the models in this pattern catalog, you can extend the AGM to consider not only your business and technology strategies, but your personal career strategy for growth and development as well.

Summary

This chapter introduced a few patterns to help you analyze your particular industry so that your tech strategy can take it into account. These included the SWOT pattern (see “SWOT”), Porter’s Five Forces (see “Porter’s Five Forces”), and the Ansoff Growth Matrix (see “Ansoff Growth Matrix”).

In the next chapter, we will drill down to the corporate level. The patterns there will help you understand how to create a strategy informed by your corporate position.

Get Technology Strategy Patterns now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.