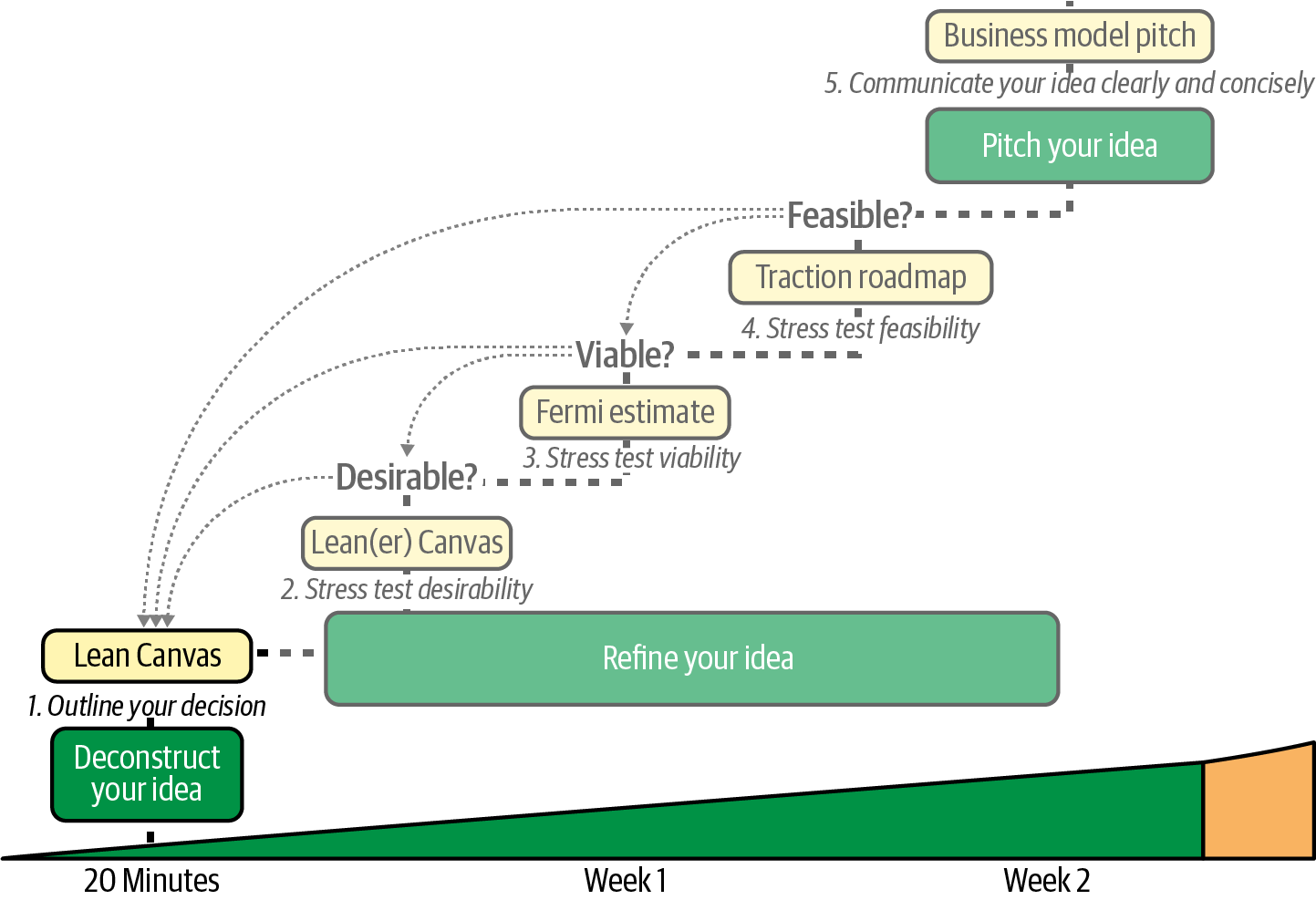

Chapter 1. Deconstruct Your Idea on a Lean Canvas

When taking on a complex project, like say building a house, you wouldn’t start by putting up walls. You’d start with some kind of an architectural plan or blueprint—even if it’s just a sketch.

Building and launching an idea is no different.

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to deconstruct your idea into a set of key assumptions using a 1-page Lean Canvas (Figure 1-1).

A Lean Canvas can be used to describe a business model, a product release, or even a single feature, making it a highly popular business planning and product management tool that’s used by millions of people around the world.

Figure 1-1. Deconstructing your idea on a 1-page Lean Canvas

Sketching Your First Lean Canvas

A business model describes how you create, deliver, and capture value (get paid) from customers.

Saul Kaplan

In this section, I’ll outline the process of sketching a Lean Canvas for your idea. The result will be a description of how you plan to create, deliver, and capture value from your customers. Here are some guidelines to keep in mind:

- Sketch the canvas in one sitting

- While it’s tempting to iterate endlessly on the whiteboard, your initial canvas should be sketched quickly—ideally in less than 20 minutes. Unlike a business plan, the goal with a Lean Canvas isn’t to achieve perfection, but to take a snapshot.

- Avoid groupthink

- If you’re part of a team, avoid creating a Lean Canvas as a group exercise. Instead, have each team member create their own snapshot first. Then get together as a group and reconcile your canvases into a single Lean Canvas. Not only will this encourage more independent perspectives and avoid groupthink, but it will also save you time.

- Know that it’s okay to leave boxes blank

- If you’re unsure about a particular box, it’s okay to leave it blank. We’ll cover the boxes on the canvas in more detail in subsequent sections.

- Embrace a 1-page constraint

- If you can’t describe your idea on a single page, it’s probably still too complex to explain. Describing your idea on a single page is not about using smaller fonts, but fewer words. It’s a lot easier to describe something in a paragraph than in a single sentence. Respecting the space constraints of the 1-page canvas is a great way to distill your business model down to its essence.

- Think in the present

- Business plans try too hard to predict the future, which is impossible. Instead, write your canvas with a “getting things done” attitude. Based on your current stage and what you know right now, what are the next sets of hypotheses you need to test to move your product forward?

- Remember there is no right order for sketching a Lean Canvas

- Sketching a Lean Canvas is like putting together a jigsaw puzzle. There is no right place to start or specific order to follow, so start with whatever box you think you understand the best and build out the rest of the canvas from there. If you still aren’t sure how to proceed, use the sample ordering in Figure 1-2 to get going.

Next, we’ll look at each of the boxes in Figure 1-2 in detail.

Figure 1-2. Sample fill order for a Lean Canvas

Customer Segments

As the Continuous Innovation Framework is heavily customer driven, the Customer Segments box of the Lean Canvas is typically a natural starting point.

Distinguish between customers and users

If you have multiple actors in your business model, aim to first identify your customers.

A customer is someone who pays for your product. A user does not.

Then identify any other actors (users, influencers, etc.) that will interact with these customers.

Examples:

-

In a blogging platform, the customer is the blog author, while the user is a reader.

-

In a search engine, the customer is the advertiser, while users are people running searches.

Model multiple perspectives

It helps to view your idea from the perspective of each actor in your business model. Each will likely have different problems, channels to reach them, and value propositions. For example, an advertiser working with a search engine may be struggling with driving awareness to their product, while the people running searches are really looking for answers to specific questions. I recommend keeping these perspectives on the same canvas and using a different color or hashtag to identify each actor’s perspective.

Home in on early adopters

As an entrepreneur, you need to simultaneously communicate a big market opportunity while staying razor-focused on your early adopters.

Your objective is to define an early adopter, not a mainstream customer.

Your list of customer segments should represent the total addressable market (TAM) for your idea, while your early adopters represent a specific subset of your TAM. This is your ideal starting customer segment (also called your ideal customer profile).

Problem

Problems, not solutions, create spaces for innovation. The Problem box is where you list the specific problem or problems you are going to tackle with your product.

List the top one to three problems

While it’s tempting to brainstorm and list many possible problems, prioritize the top one to three issues that you believe are most pressing for your customers.

List existing alternatives

Document how you think your early adopters currently address these problems. Unless you are solving a brand new problem (unlikely), solutions probably already exist. These solutions may not be from an obvious competitor.

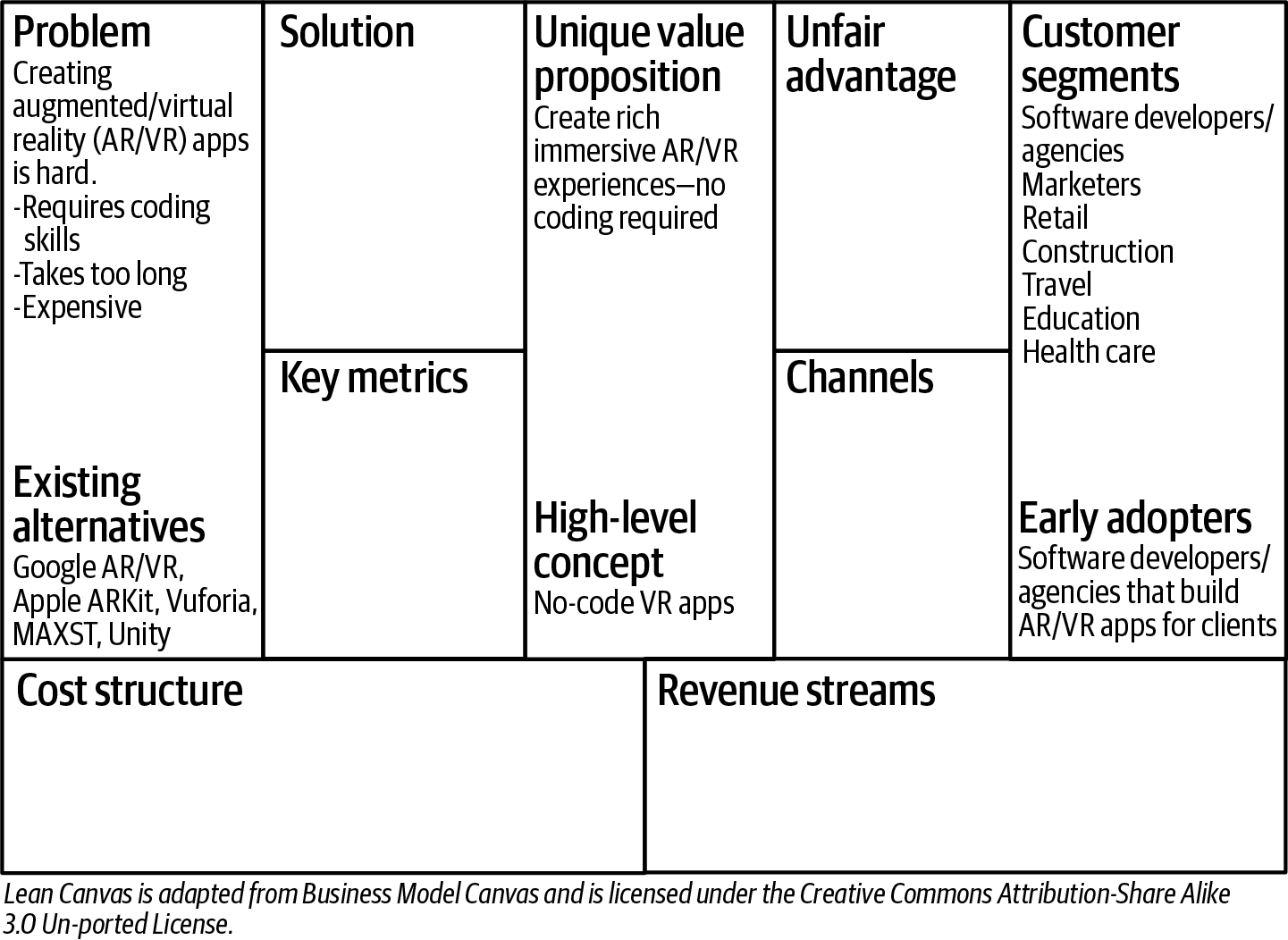

Steve tackles the Customer Segment/Problem quadrant

Before Steve takes on sketching his first Lean Canvas, he digs up the original vision statement he wrote down a year ago:

To create an alternate virtual world (a metaverse) as vast and rich as the real world and make it universally accessible and useful.

He is tempted to put down “everybody” under Customer Segments, but he remembers Mary’s advice against defining too broad a customer segment: “When you’re trying to market to everyone, you reach no one.”

He instead turns his focus to who he considers his ideal early adopters and writes down “software developers.” While he envisions that his platform will eventually allow anyone to create rich immersive AR/VR applications, it will be easiest to start with software developers that already build or want to build these kinds of applications.

Under this segment, he lists various industries that are likely to adopt AR/VR technologies over the next several years. Next, he turns his attention to listing out the top problems he plans to address and captures the top existing alternatives on the Lean Canvas.

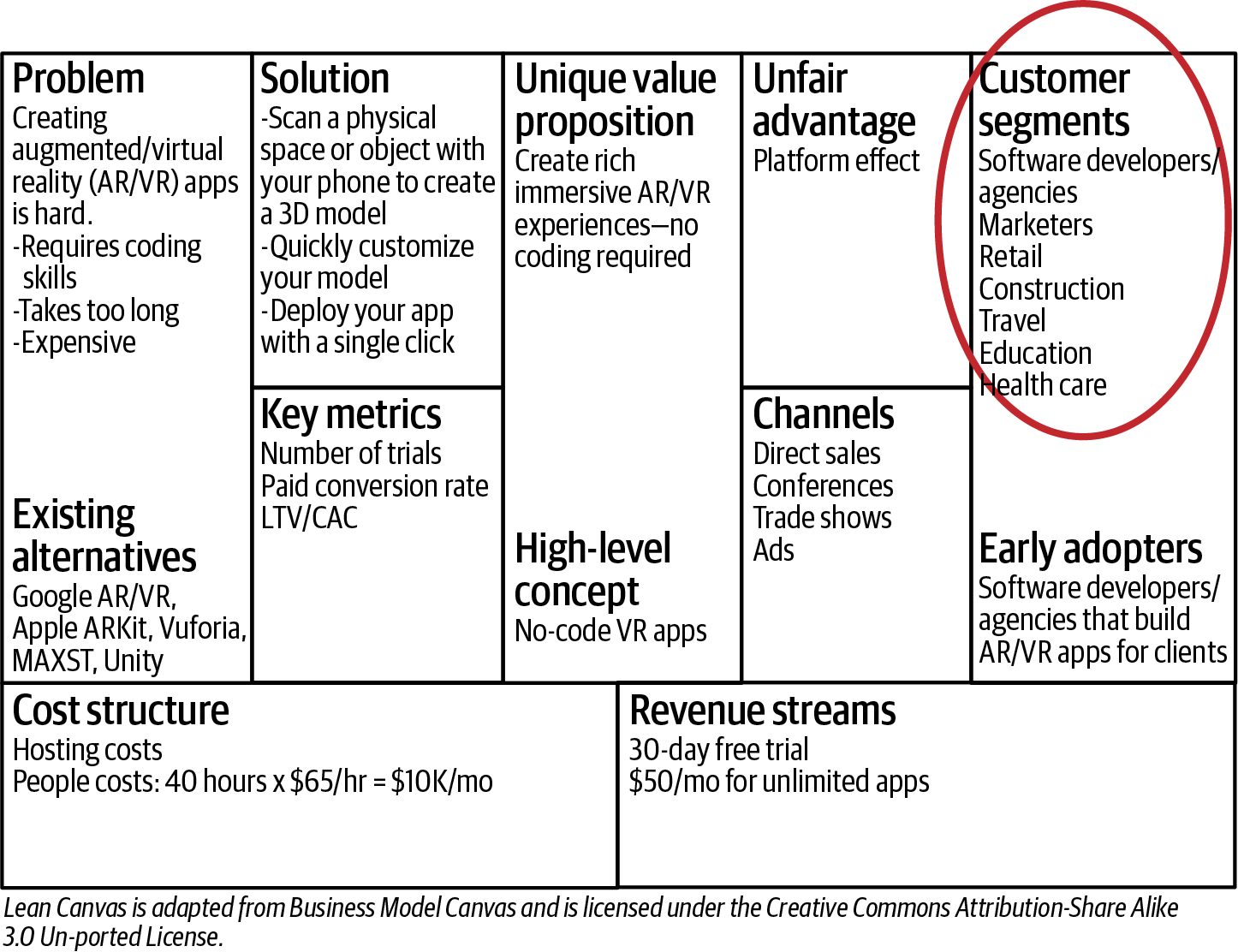

Figure 1-3 shows what his Customer Segments and Problem boxes look like after just a few minutes of pondering.

Figure 1-3. Steve’s problem and customer segments

Unique Value Proposition

Dead center in the Lean Canvas is a box for your unique value proposition (UVP). This is one of the most important boxes on the canvas and also the hardest to get right.

Defining a UVP forces you to answer the question: why is your product different and worth paying attention to?

Before paying for your product with money, customers pay you with attention. Your UVP is hard to get right because you have to distill the essence of your product in a few words that can fit in the headline of your landing page. Additionally, your UVP needs to be different in order to stand out from the competition, and that difference needs to matter to your customers.

The good news is that you don’t have to get this perfect right away. Like everything on the canvas, you start with a best guess and iterate from there.

Connect to your customer’s number one problem

The key to crafting an effective UVP is connecting it to the number one problem you are solving for your customers. If that problem is indeed worth solving for them, you’re more than halfway there already.

Target early adopters

Too many marketers try to target the “middle” of their customer segments, in the hopes of reaching mainstream customers, and in the process they water down their message. Your product is not ready for mainstream customers yet. Your sole job should be to find and target early adopters, which requires bold, clear, and specific messaging.

Focus on outcomes

You’ve probably heard about the importance of highlighting benefits over features. But benefits still require your customers to translate them to their worldview. A good UVP gets inside customers’ heads and focuses on the benefits they will derive from using your product—that is, the desired outcomes.

So, for instance, if you are creating a résumé-building service:

-

A feature might be “professionally designed templates.”

-

The benefit would be “an eye-catching résumé that stands out.”

-

And the desired outcome would be “landing your dream job.”

Keep it short

Most advertising platforms limit the number of characters in the primary headline field to 120. Pick your words carefully, and avoid empty fillers.

Answer what, who, and why

A good UVP needs to clearly describe what your product is for and who it’s for. The “why” is often hard to fit into the same statement, so a sub-headline is often used for this.

Here’s an example:

-

Product: Lean Canvas

-

Headline: Communicate Your Idea Clearly and Concisely to Key Stakeholders.

-

Sub-headline: A Lean Canvas replaces a long and boring business plan with a 1-page business model that takes 20 minutes to create and gets read.

Create a high-concept pitch

Another useful exercise when crafting a UVP is creating a high-concept pitch, popularized as an effective pitching tool by Venture Hacks in the ebook Pitching Hacks. High-concept pitches are also used heavily by Hollywood producers to distill the general plot of a movie into a memorable sound bite.

Examples might include:

-

YouTube: “Flickr for video”

-

Aliens (movie): “Jaws in space”

-

Dogster: “Friendster for dogs”

The high-concept pitch should not be confused with a UVP and is not intended to be used on your landing page. There is a danger that the concept the pitch is based on might be unfamiliar to your audience. For this reason, the high-concept pitch is more effectively used in scenarios where you want to quickly get your idea across and make it easy to spread, such as after a customer interview. We’ll cover a specific use of the high-concept pitch in Chapter 8.

Steve crafts his UVP

Given that all the existing alternatives require technical know-how and coding knowledge, Steve decides to use “no-code” as the keyword to position his UVP around (see Figure 1-4).

Figure 1-4. Steve’s UVP

Solution

You are now ready to tackle your solution.

Know that it is fairly common for your customer problems to get reprioritized or completely replaced with new ones after just a few customer conversations. For this reason, I recommend not getting carried away with fully defining your solution just yet. Rather, simply sketch out the simplest thing you could possibly build to address each problem listed on your Lean Canvas.

Bind a solution to your problem as late as possible.

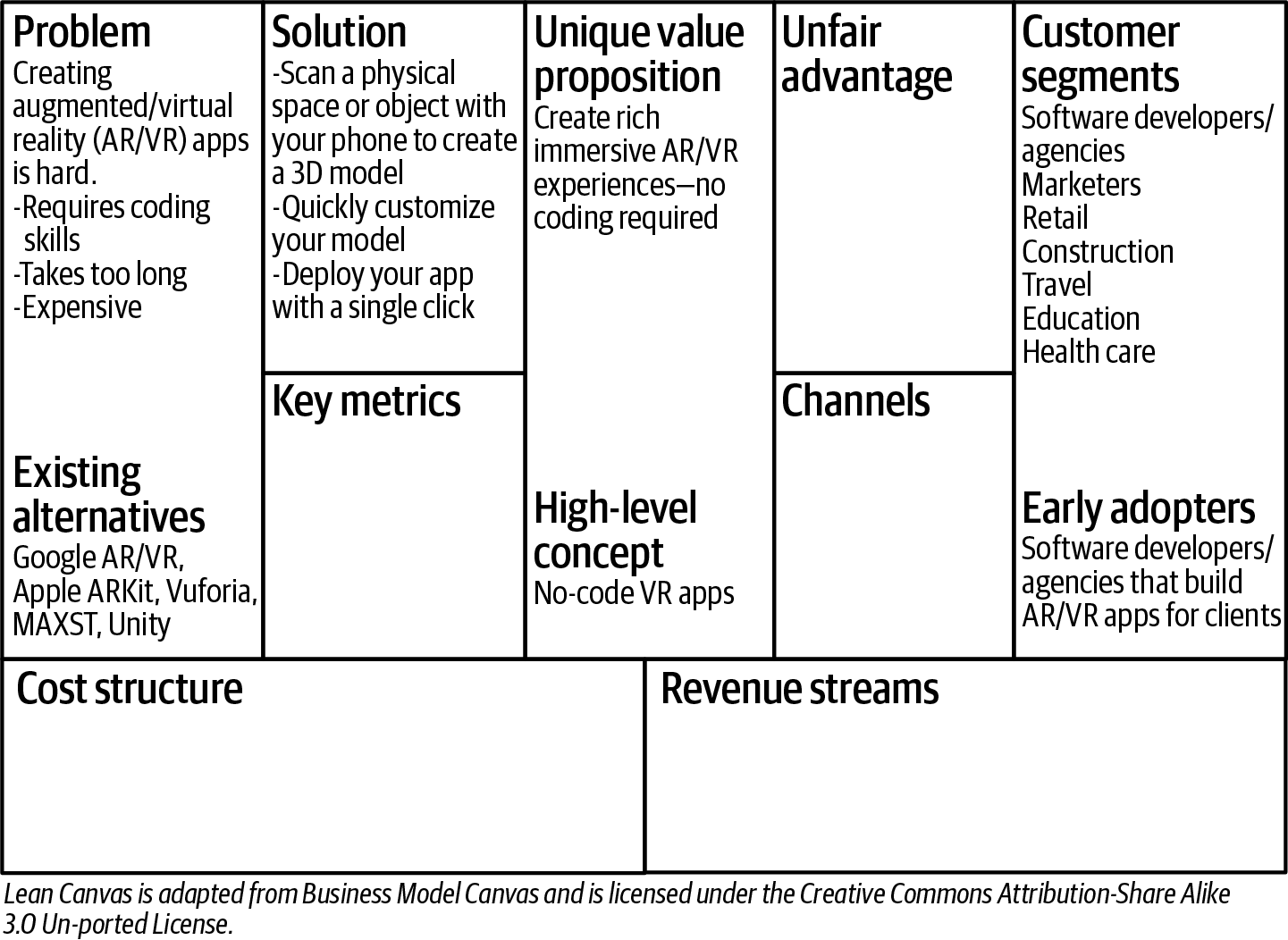

Steve defines a solution

Based on his list of problems, Steve creates a shortlist of top features that address each problem (see Figure 1-5).

Figure 1-5. Steve’s solution

Channels

If a product is launched in a forest, does it make a sound? Failing to build a clear path to customers is among the top reasons why startups fail.

The initial goal of a startup is to learn, not to scale. So, at first, it’s OK to rely on any channels that get you in front of potential customers.

The good news is that following a “customer discovery/interview” process (which we’ll discuss in Chapter 7) forces you to build a path to “enough” customers early. However, if your business model relies on acquiring large numbers of customers to work, that path may not scale beyond the initial stages, and it’s quite possible you’ll get stuck later.

For this reason, it’s equally important to think about your scalable channels from day one so that you can start building and testing them early.

While there are a plethora of channel options available, some channels may be outright inapplicable to your startup, while others may be more viable during the later stages of the startup.

Steve outlines some possible paths to customers

Since Steve plans on targeting software developers and agencies as early adopters, he plans to start with warm referrals, direct sales, conferences, and trade shows as initial channels, and possibly scaling later using advertising (see Figure 1-6).

Figure 1-6. Steve’s channels

Revenue Streams and Cost Structure

The bottom two boxes, labeled Revenue Streams and Cost Structure, are used to model the viability of the business.

Revenue streams

A lot of startups choose to defer the “pricing question” to a later stage, but this is a mistake. Here’s why:

- Price is part of the product

- Suppose I place two bottles of water in front of you and tell you that one costs $0.50 and the other costs $2. Despite the fact that you wouldn’t be able to tell them apart in a blind taste test (the products are similar enough), you might be inclined to believe (or at least wonder whether) the more expensive water is of higher quality. Here, price has the power to change your perception of the product.

- Price defines your customers

- More interesting is the fact that the bottled water you pick determines your customer segment. From the existing market for bottled water, we know there is a viable business for bottled water at both price points. What you charge signals your positioning on which customers you want to attract.

- Getting paid is the first form of validation

- Getting a customer to give you money is one of the hardest challenges, and is an early form of product validation.

Revenue is the difference between a hobby and a business.

Cost structure

How do you determine the cost structure of your idea/product? That is, how much will it cost to make your product and keep your business running?

Rather than thinking in terms of three- or five-year forecasts, it’s better to take a more stage-based approach. Focus on your most immediate short-term milestones for three to six months from now. First, model the runway you will need to define, build, and launch your MVP. Then revise after you get there. Questions to consider include:

-

What will it cost you to define, build, and launch your MVP?

-

What will your ongoing burn rate look like (salaries, office rent, etc.)?

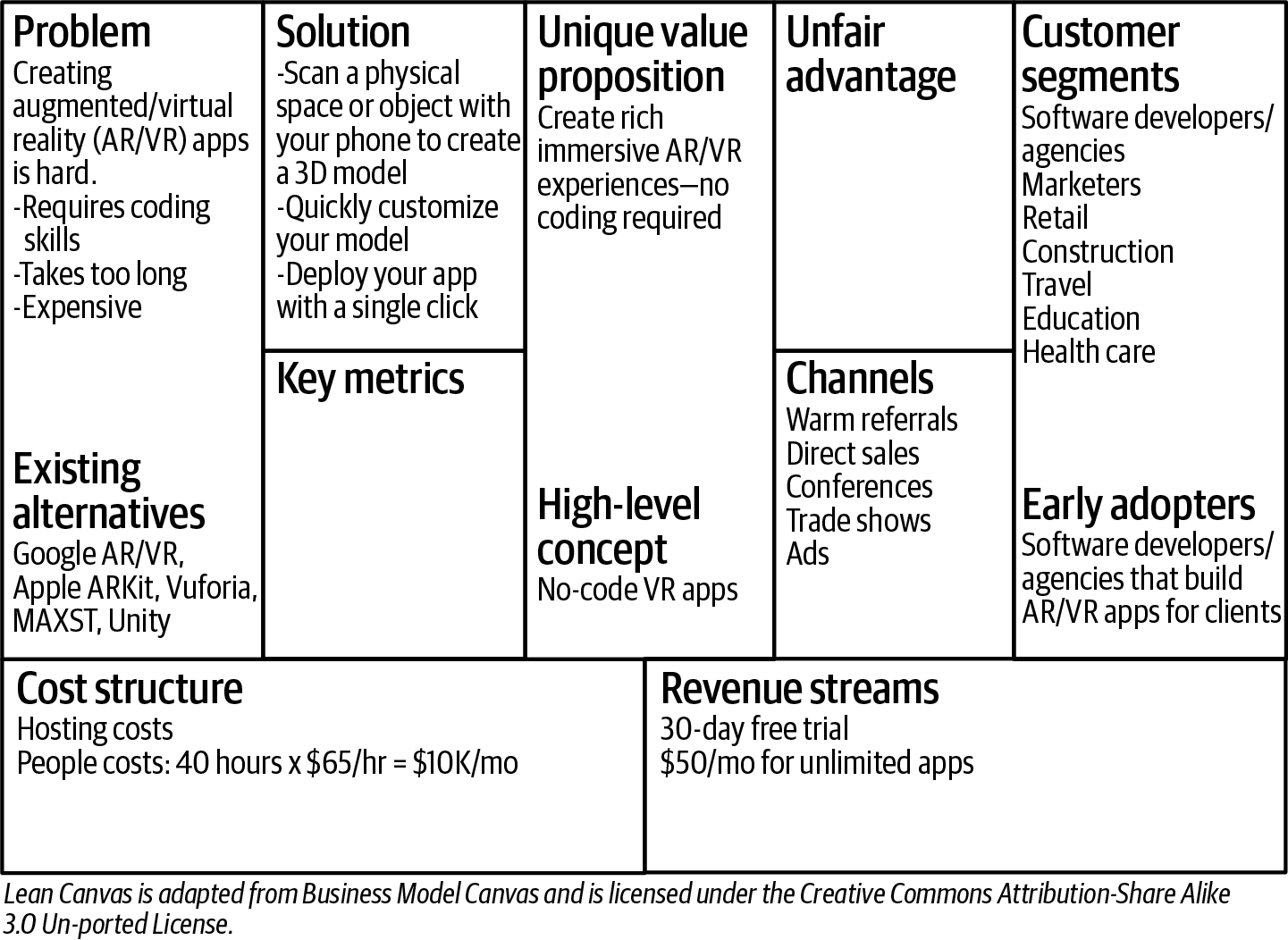

Steve thinks through his cost structure and revenue streams

While Steve had found a comfortable groove of self-funding his project through consulting revenue, the competitor launch (Virtuoso X) was his wake-up call to speed things up. Steve sets a goal to get his MVP launched within the next six months and outlines his costs, which are mostly his time.

Steve had not given any serious thought to his pricing model up until now, but decides to heed the advice of not deferring this until later. He figures he should anchor his pricing against other software development tools, and finds that they vary from free to several hundred dollars a month. He decides to go down the middle and picks the most popular entry-level pricing model of $50/mo with a free 30-day trial.

For his cost structure, Steve estimates his runway needs for the next six to nine months. He anticipates working alone and continuing to bootstrap his product until he can attract enough customers or investors. Figure 1-7 shows what Steve’s Lean Canvas looks like with these boxes filled in.

Figure 1-7. Steve’s cost structure and revenue streams

Key Metrics

Every business has a few key numbers that can be used to measure how well the business is performing. These numbers are important for both measuring progress and identifying hot spots in the business model. I’ll give you a few examples here.

Prefer outcome metrics versus output metrics

Instead of measuring how much stuff you’re building (outputs), focus on measuring how many people are using your product and how (outcomes). The right outcome metrics tend to be customer-centric versus product-centric.

Examples of outcome metrics include:

Prioritize leading indicator metrics versus trailing indicator metrics

Find the key number that tells you how your business is doing in real-time before you get the sales report.

Norm Brodsky and Bo Burlingham, The Knack

While you’ll need to measure and report on metrics like revenue and profit, understand that these are trailing indicators, not leading indicators of progress.

Here are some examples of leading indicator metrics:

-

Number of qualified leads in your pipeline

-

Number of trials/pilots

-

Customer attrition rate (churn)

Study analogs

Research what metrics other companies in your product space/industry use to measure and communicate progress to their stakeholders.

Here are some examples:

-

-

Lifetime value (LTV)

-

Cost to acquire customers (CAC)

-

Monthly recurring revenue (MRR) or annual recurring revenue (ARR)

-

-

Typical ad-based metrics:

-

Daily active users (DAU) and monthly active users (MAU)

-

Click-through rate (CTR)

-

Cost per impression (CPM) and cost per click (CPC)

-

-

Typical marketplace metrics:

-

Buyer to seller ratio

-

Average transaction size

-

Take rate

-

Steve identifies a few key metrics

In the Key Metrics box, Steve decides to use the starting list of metrics for a SaaS product identified in the previous section (see Figure 1-8).

Figure 1-8. Steve’s key metrics

Unfair Advantage

This is usually the hardest section in the canvas to fill in, which is why I leave it for last. Most founders list things as competitive advantages that really aren’t, such as passion, lines of code, or features.

Another frequently cited advantage in business models is the “first-mover” advantage. However, it doesn’t take much to see that being first can actually be a disadvantage, as most of the hard work of paving new ground (risk mitigation) falls on your shoulders—only to be capitalized on by fast followers, who may overtake you unless you’re able to constantly outpace them with a real unfair advantage. Think of Ford, Toyota, Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Facebook: again, none of these companies were first movers.

An interesting perspective to keep in mind is that anything worth copying will be copied, especially once you start to demonstrate a viable business model.

Imagine a scenario where your cofounder steals your source code, sets up shop in Costa Rica, and slashes prices. Do you still have a business? How about if Google or Apple launches a competitive product and drops the price to $0?

You have to be able to build a successful business in spite of that—an observation that led Jason Cohen to offer the following definition: “A real unfair advantage is something that cannot be easily copied or bought.”

Here are some examples of real unfair advantages that fit this definition:

-

Insider information

-

The right “expert” endorsements

-

A dream team

-

Personal authority

-

Network effect

-

Platform effect

-

Community

-

Existing customers

-

SEO ranking

A great illustration of the difference between a real unfair advantage and a fake unfair advantage is the difference between organic SEO ranking versus paid keywords for search engine marketing. Keywords can be easily copied and bought by your competitors, while organic ranking has to be earned.

Some unfair advantages can also start out as values that become differentiators over time. For example, Zappos CEO Tony Hsieh believed strongly in creating happiness for his customers and employees. This manifested itself in many company policies that, on the surface, didn’t make much business sense, such as allowing customer service representatives to spend as much time as was needed to make a customer happy and offering a 365-day return policy with two-way paid shipping. But these policies served to differentiate the Zappos brand and helped build the large, passionate, and vocal customer base that played a large role in the company’s eventual $1.2 billion acquisition by Amazon in 2009.

What do you do if you don’t have an unfair advantage on day one?

Most entrepreneurs don’t have an unfair advantage at the outset of their idea. Consider Mark Zuckerberg. He wasn’t the first to build a social network, and a number of his competitors already had a huge head start with millions of users and millions of dollars in funding. That didn’t prevent him from building the largest social network on the planet.

Start with an unfair advantage story

While Mark didn’t have an unfair advantage on day one, he had an unfair advantage story. He knew his unfair advantage needed to come from large network effects. This clarity of focus helped Facebook develop a systematic launch and growth strategy that helped the company eventually realize this advantage.

Leave the unfair advantage blank

If an unfair advantage story isn’t readily apparent, it is always better to leave the Unfair Advantage box blank rather than stuffing it with a weak unfair advantage.

Embrace obscurity

As mentioned previously, the good news with unfair advantages is that you don’t need one from the outset. When you are just starting out, embrace obscurity to build something valuable without calling out competitor attention, and keep searching for your true unfair advantage.

Steve ponders his unfair advantage story

Steve normally would have put down software IP (intellectual property) as his unfair advantage, but after learning about real and fake unfair advantages, he decides instead to rely upon an unfair advantage story built on the “platform effect” (Figure 1-9). If he can get enough software developers and agencies to build enough killer apps, that will accelerate his vision of creating a massive reusable library of 3D objects, creating a flywheel that will make it easier for everyone to build more apps faster and establishing his platform as the platform of choice for AR/VR applications.

Figure 1-9. Steve’s unfair advantage

Refining Your Lean Canvas

Sketching out a Lean Canvas quickly is a great first step for taking stock of your big idea and visualizing your business model as a set of assumptions. That said, most entrepreneurs either go too broad or too narrow with their first canvases. This is a Goldilocks problem.

If you struggled to fit your idea on a single page, chances are you went too broad. When you go too broad, your canvas becomes watered down and undifferentiated. I’ve worked with several startups that felt the problems they were solving were so universal, they applied to everyone.

When you try to market to everyone, you reach no one.

While you might be aiming to build a mainstream product, you need to start with a specific customer in mind. Even Facebook, with its now 500 million+ users, was originally oriented toward a very specific user group: Harvard University students. At the other extreme, when you go too narrow, you face the danger of falling into a local maximum trap and not finding the best possible market for your idea.

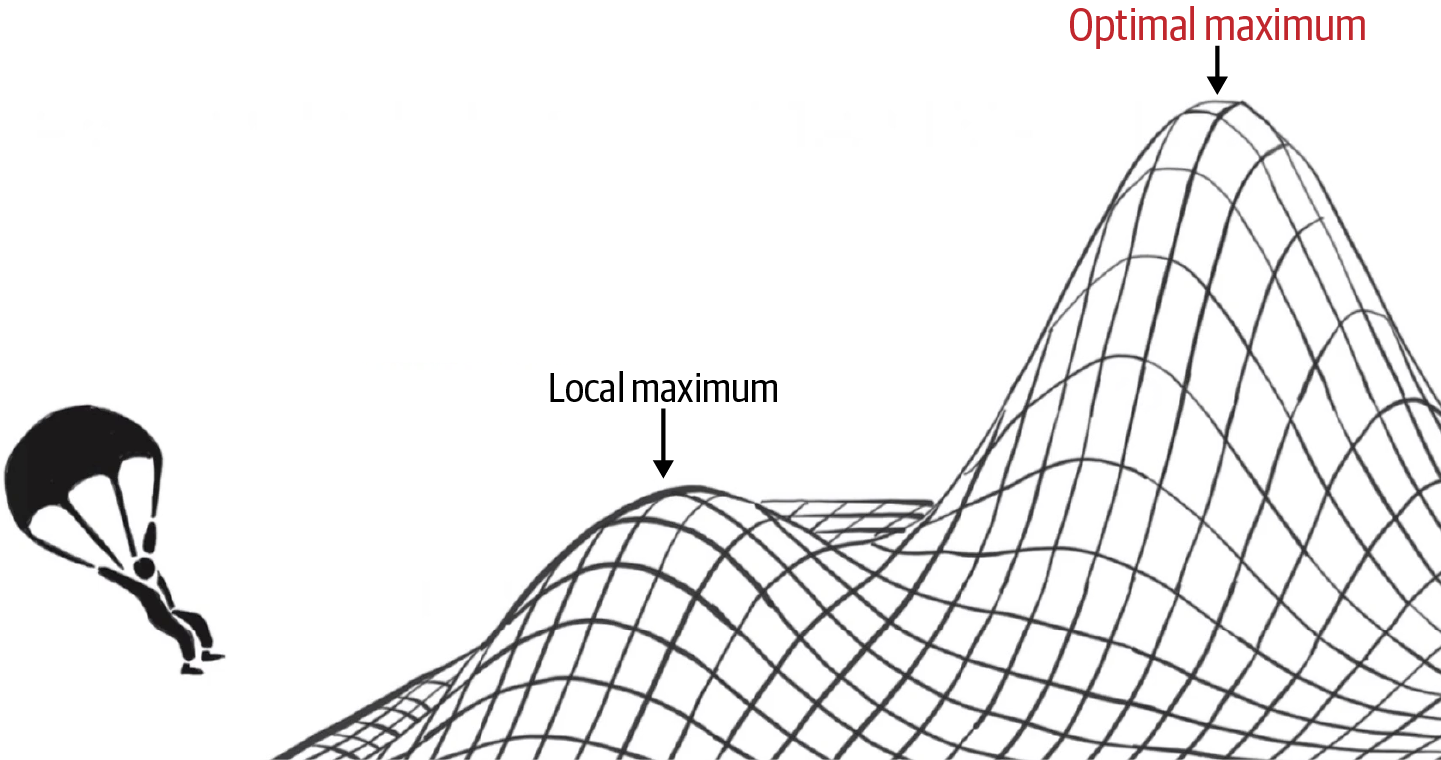

This is illustrated in Figure 1-10 as the hill-climbing problem.

Figure 1-10. The hill-climbing problem

Imagine you are blindfolded and given the task of finding the highest point in this landscape. You might be able to fumble your way to the top of the small hill and declare it the highest point—only to find out, once your blindfold is off, that there is a neighboring mountain right next to you that you missed.

So, How Do You Avoid the Goldilocks Problem?

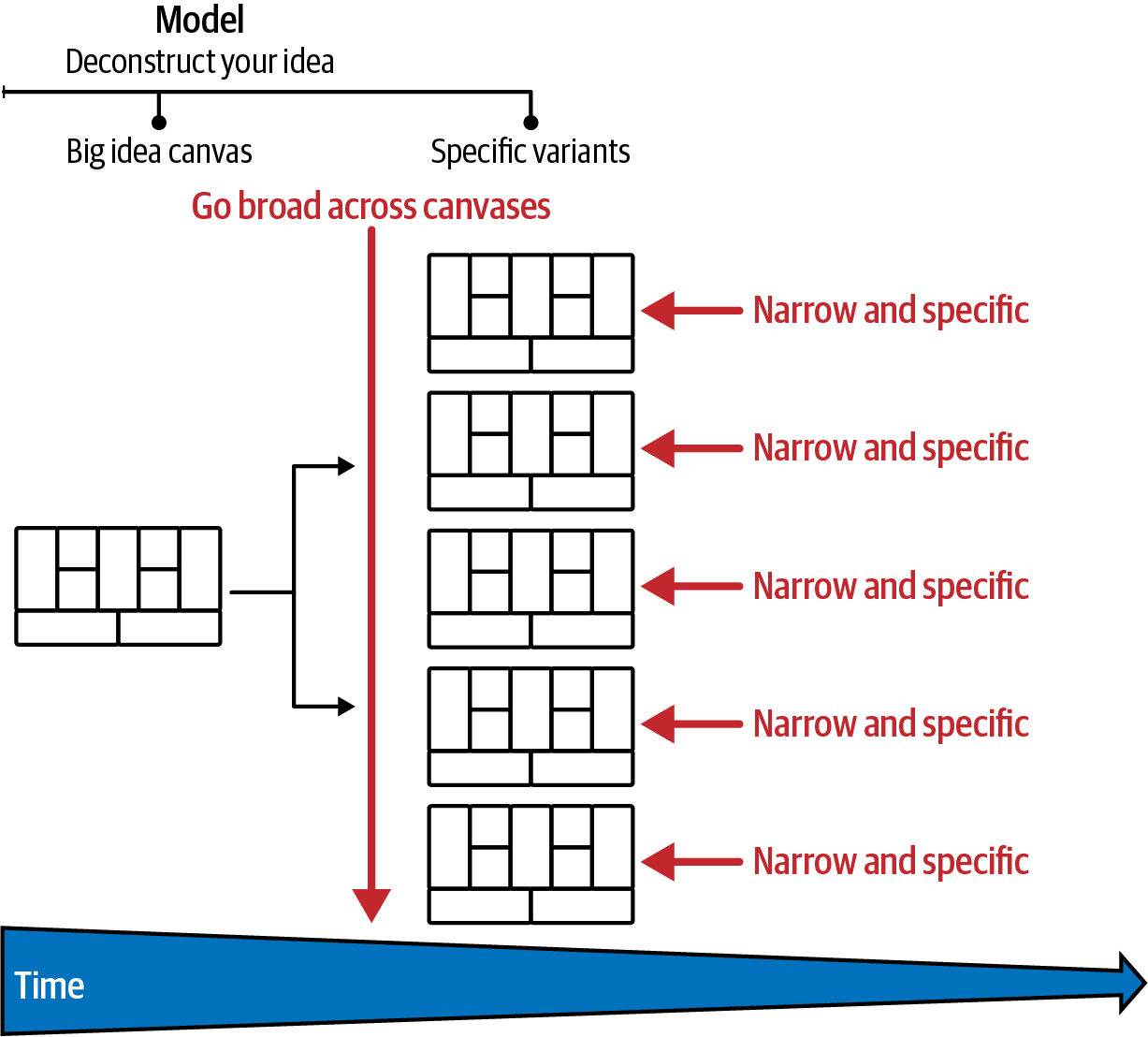

You need a strategy that allows you to simultaneously go broad and narrow. The way you do this is by splitting your first Lean Canvas (your “big idea canvas”) into additional canvases (Figure 1-11).

Figure 1-11. Splitting your big idea canvas into one or more variants

Each of your additional canvases needs to be narrow and specific, but you can and should go broad across these canvases by sketching out multiple possible variants of the same idea. For example, a photo-sharing service could be targeted at consumers or businesses. Within businesses, there could be many possible business models to consider. Each of these variants can and should be explored on a different canvas.

While there’s no guarantee that you’ll uncover a mountain with this approach, you can probably appreciate that by casting a wider net and staying open to all possibilities early you can avoid getting tunnel-visioned around a single implementation of your idea. After you’ve short-listed your best variants, you can systematically prioritize and test your ideas over time. Remember, building a business model requires a search mindset, not an execution mindset.

How Do You Know When to Split Your Lean Canvas?

The reason most Lean Canvases become too broad is that they try to capture too many business model stories on a single canvas. Your objective should be to describe a single business model story per Lean Canvas.

There are three basic business model archetypes: direct, multisided, and marketplace. If you find yourself mixing multiple types of models on one Lean Canvas, split them into separate canvases. Let’s take a look at each.

Direct

Direct business models are the most basic and widespread type. They are one-actor models where your users become your customers. Starbucks is an example of a company with a direct business model; an example Lean Canvas for this company is shown in Figure 1-12.

Figure 1-12. Starbucks Lean Canvas

With a direct business model, your Lean Canvas should capture your total addressable customer segment as a single entry under Customer Segments, and your ideal starting subsegment under Early Adopters.

Multisided

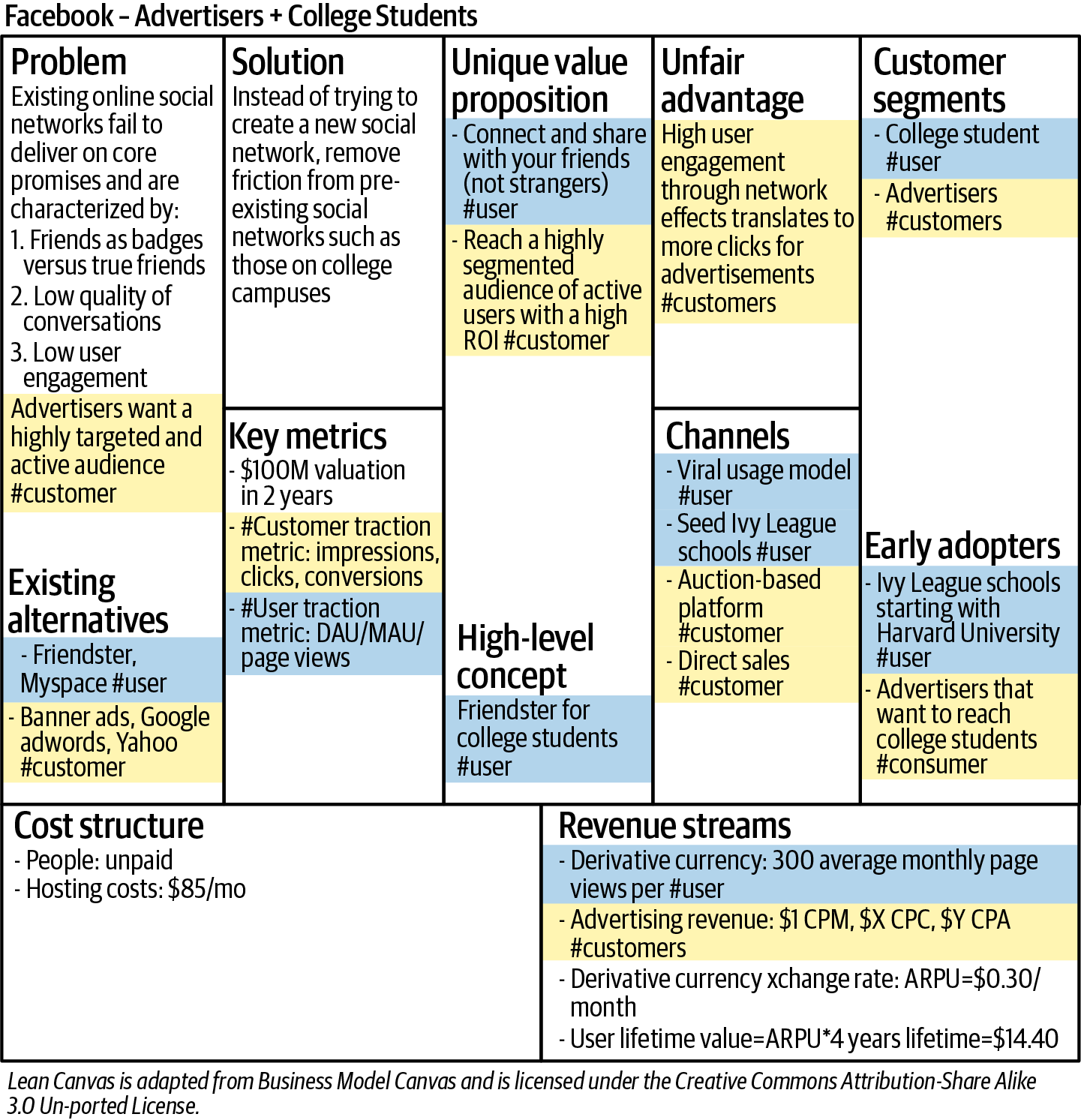

In a multisided business model, the goal is still to create, deliver, and capture value from users, but that value is monetized through different customers. These are two-actor models made up of users and customers.

Users typically don’t pay for usage of your product with a monetary currency, but rather with a derivative currency. This derivative currency, when aggregated across enough users, represents a derivative asset that your customers pay to acquire. Facebook is an example of a company with a multisided model; at the time of launch in 2004, the users were college students and the customers were advertisers.

An example Lean Canvas for Facebook is shown in Figure 1-13.

Figure 1-13. Facebook Lean Canvas—user perspectives (college students) are tagged #user, and customer perspectives (advertisers) are tagged #customer

With a multisided business model, your Lean Canvas should model your idea from the perspective of both your users and your customers. For example, from the user’s perspective, an alternative to Facebook would be Friendster.

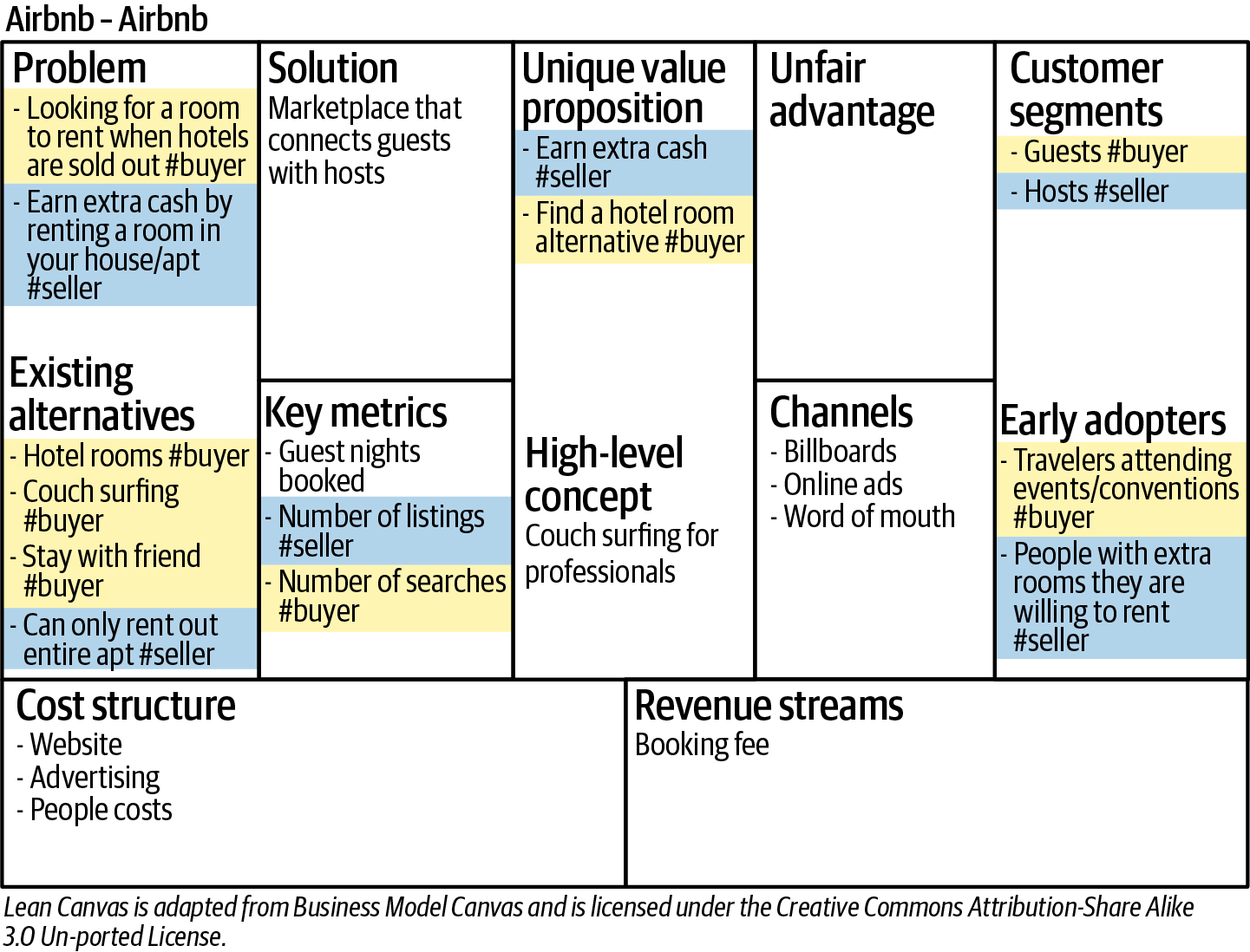

Marketplace

Marketplace business models are a more complex variant of the multisided model that warrants its own category. Like multisided models, these are multiactor models made up of two different segments: in this case, buyers and sellers. Airbnb is an example of a company with a marketplace model; a Lean Canvas for this company is shown in Figure 1-14.

Figure 1-14. Airbnb Lean Canvas—buyer perspectives are tagged #buyer, and seller perspectives are tagged #seller

Here too, you should model your idea from both the perspective of the buyer and the seller. For example, from the buyer’s perspective, alternatives to Airbnb are hotel rooms, couch surfing, etc.

Strive for simplicity, not complexity. Simple is hard enough.

It is possible to find more complex models in practice that layer these basic archetypes. The thing to keep in mind is that even these more complex models started with a basic model at the outset. Gall’s law states that a complex system that works is invariably found to have evolved from a simple system that worked.

Steve Splits His Big Idea Canvas into Specific Variants

Steve revisits his Lean Canvas and immediately recognizes that he has identified too many customer segments (Figure 1-15).

Figure 1-15. Too many customer segments

“Do they all belong to the same business model?” Stever wonders.

After a few minutes of staring at his Lean Canvas and using his newly acquired knowledge of business model archetypes, he starts to recognize distinct business models intertwined on his Lean Canvas.

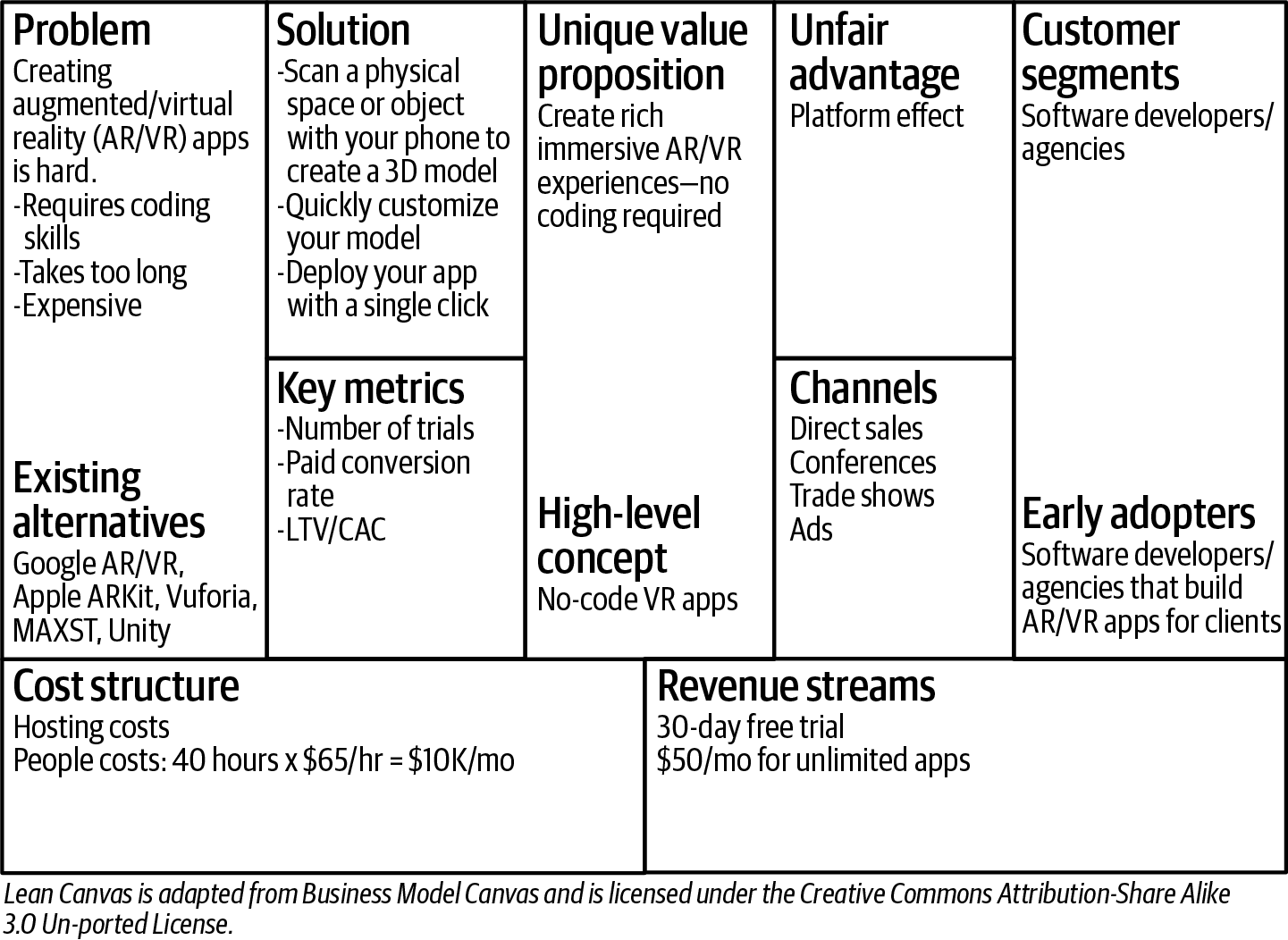

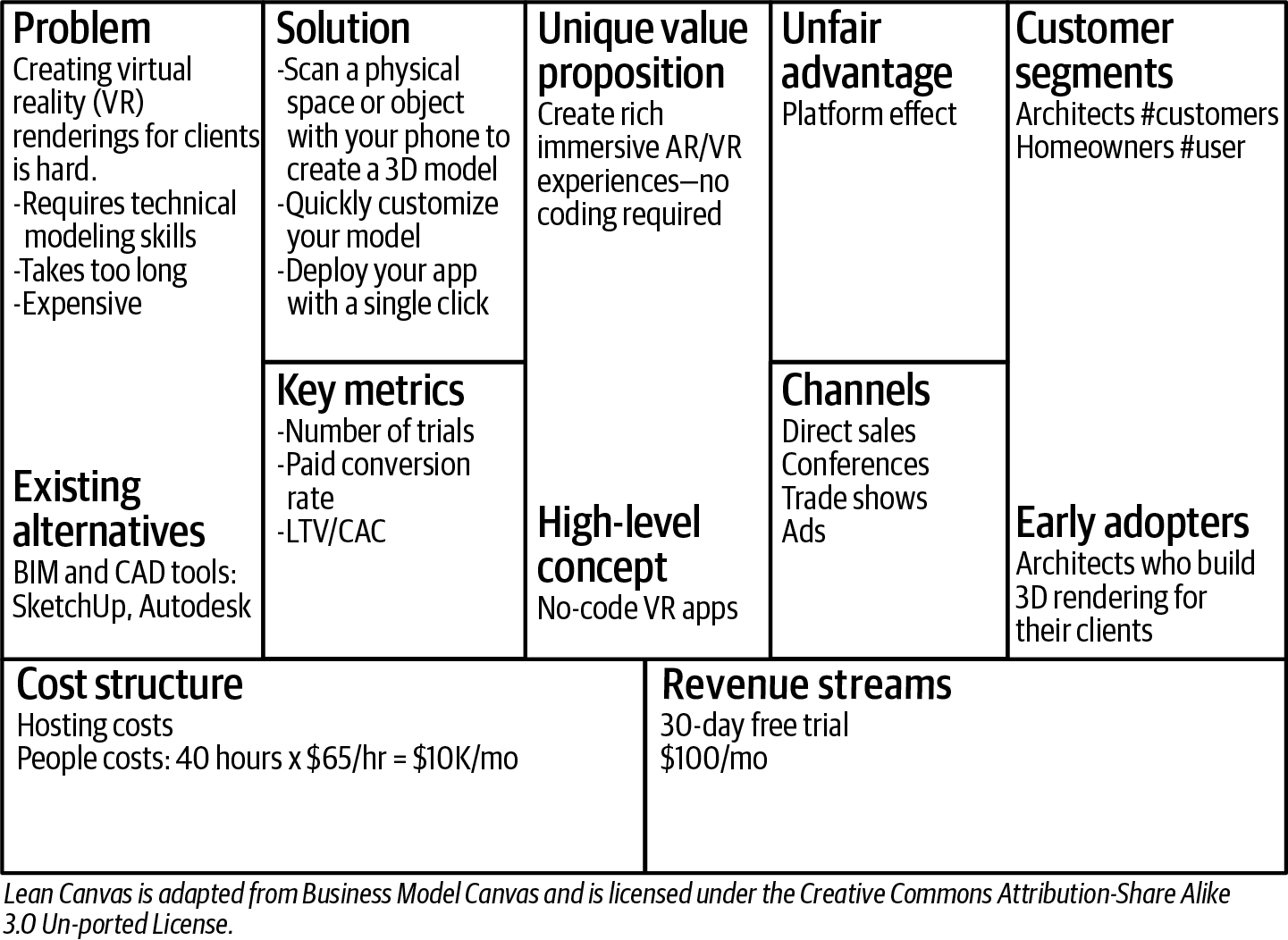

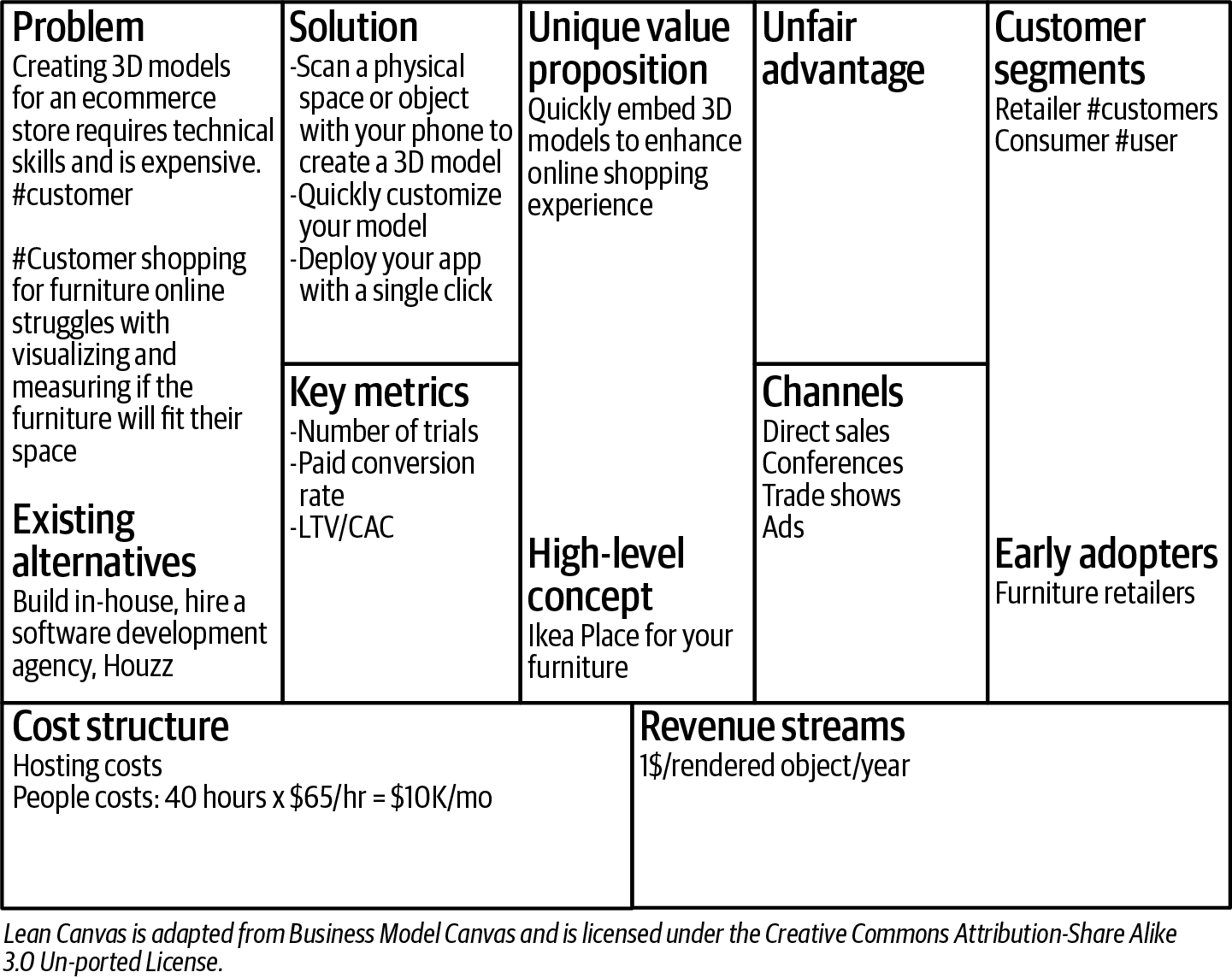

He gets to work splitting them into separate canvases and decides to focus on what he considers his top three variants (Figures 1-16 through 1-18).

Figure 1-16. Software Developers Lean Canvas

Figure 1-17. Home Construction Lean Canvas

Figure 1-18. Retail Furniture Lean Canvas

Steve can immediately see that these variants are clearer than his original big idea canvas.

What’s Next?

It’s tempting to “rush out of the building” after completing your first Lean Canvas sketch and immediately start testing out your business model on customers. It’s even possible to rapidly find clusters of problems, pitch an offer, build a quick MVP, and charge your customers from day one—which sounds exactly like what we should do.

So what’s wrong with this approach?

The danger is getting stuck with a suboptimal business model six or nine months down the line that either doesn’t match your ambition or doesn’t scale.

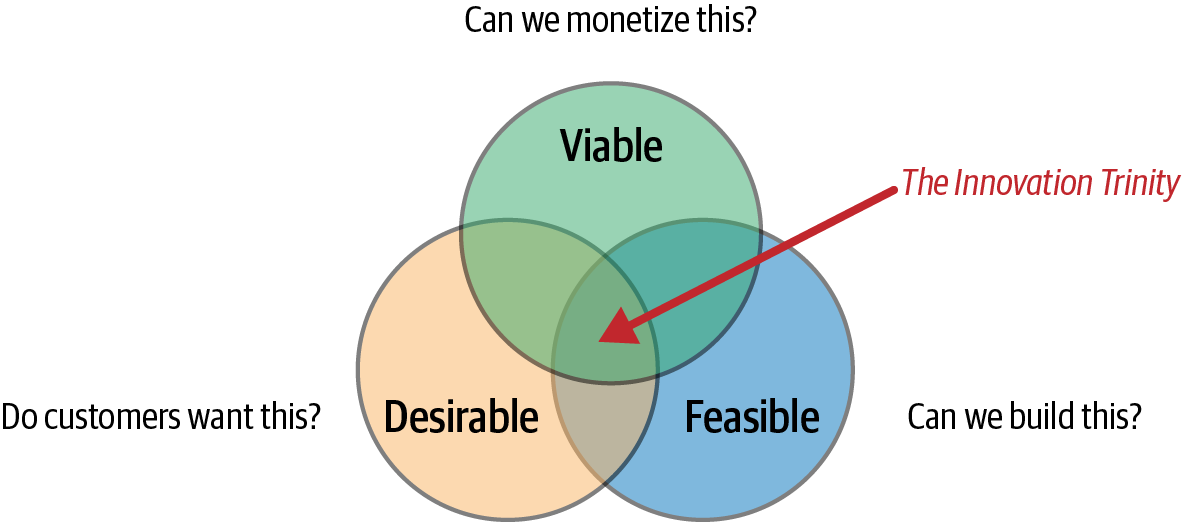

For an idea to be successful, it must constantly balance three types of risks: customer, market, and technical. These risks can be more easily visualized through what IDEO has popularized as the Innovation Trinity: desirability, viability, and feasibility (Figure 1-19).

Figure 1-19. The Innovation Trinity

Before engaging in several weeks or months of customer validation, it’s prudent to spend a few more hours (inside the building) stress testing your business model and tightening up any obvious cracks or flaws in your thinking.

You do this by subjecting your business model to three stress tests that check for:

-

Desirability (Do your customers want this?)

-

Viability (Can you monetize this?)

-

Feasibility (Can you build this?)

Get Running Lean, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.