Chapter 1. Why Cloud Native and Not Just Cloud?

In the late 1990s when I started my career, the digital landscape was in the early stages of transformation. Companies were introducing email servers for the first time as employees began to familiarize themselves with PCs sitting on their desks. As the hands-on tech guy, my job was to set up these PCs and install email servers in server rooms, connecting them to the internet through dial-up modems or ISDN lines.

Back then, a computer room was often just an air-conditioned cupboard that housed the company’s entire computing infrastructure. I distinctly remember installing a server next to a washing machine–sized DEC VAX, a computing relic from the 1980s, which continued to run just as it was pictured in my computer science textbooks.

With the dot-com boom of the early 2000s, a robust and uninterrupted internet presence became critical for businesses. Large corporations responded by investing in on-premises data centers, specialized facilities equipped to host IT equipment with multiple redundant internet connections and power supplies.

However, building a dedicated data center wasn’t feasible for smaller companies. Instead, they could rent space in shared colocation data centers, or “CoLos.” But this posed a significant challenge for emerging internet startups: What happens if you become an overnight success? What if your user base explodes from a thousand to a million users overnight?

Would it be wiser to start with servers that can accommodate a thousand users and risk your website crashing if you can’t scale quickly enough? Or should you preemptively invest in the capacity to serve millions of users, in the event of rapid growth? The latter choice would require significant funding, possibly reliant on a venture capitalist with deep pockets. Balancing this risk and potential growth became a pressing question for many businesses during this time.

Emergence of the Cloud Era

The advent of the public cloud marked a significant turning point. Launched in 2006, Amazon Web Services (AWS) began offering on-demand EC2 servers, and by 2008, anyone with a credit card could virtually set up a server in an instant. The ability to seamlessly scale up server capacity as demand increased was a game changer. Startups could begin with modest infrastructure and then expand as they became more profitable, thus minimizing initial investments and reducing the cost of innovation.

In 2008, Google followed suit with the Google App Engine (GAE), pioneering one of the first platforms as a service (PaaS). With GAE, developers could write a web application in PHP or Python and deploy it on Google’s public cloud, all without the need to manage server infrastructure. Despite GAE’s potential, it presented challenges for developers like me, accustomed to working with traditional applications and relational databases, due to its unfamiliar restrictions.

As the 2010s unfolded and cloud computing surged in popularity, companies with pricey on-premises data centers began eyeing their digital native competitors with envy. Companies like Netflix, Airbnb, and Slack. These newer entities, born in the cloud and deploying software on platforms like AWS, Google Cloud, and Microsoft Azure, were rapidly releasing competitive products without bearing the burdensome costs of maintaining a data center. They were also leveraging additional on-demand cloud services, including machine learning and AI, which offered unprecedented capabilities.

Established companies, rooted in traditional data center operations, found the allure of the cloud irresistible for several reasons, as shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1. Go faster, save money, and do more

These were typically:

- Go faster

-

Enhance developer productivity by leveraging the cloud’s on-demand, scalable resources and a wide range of prebuilt services. This allows developers to focus on core application logic instead of infrastructure management.

- Save money

-

Decrease infrastructure or operational costs by shifting from capital expenditure (CapEx) for hardware and maintenance to operational expenditure (OpEx) for on-demand services, improving cash flow and reducing upfront investments.

- Do more

-

Access resources and services that are impractical in an on-premises setup, such as vast scalable storage options, powerful data analytics tools, machine learning platforms, and advanced AI services.

The critical misstep these organizations often make is migrating to the cloud without understanding its unique nature, the added complexity, and how it necessitates changes in software development practices. As a result, rather than enhancing efficiency and reducing costs, the cloud can sometimes introduce additional complications and expenses, thus slowing progress and increasing expenditure. Therefore, the frequently promised benefit of “run your mess for less” rarely materializes, underscoring the importance of a well-informed and strategic approach to cloud migration.

Navigating the Cloud Migration

I am a great admirer of Marie Kondo, the Japanese organizing consultant who brings joy to homes by transforming cluttered spaces into realms of tranquility and efficiency.

Picture a cupboard brimming with two decades of accumulated possessions—a mix of obsolete, broken, and unopened items. Among these are items you’ve bought in duplicate, unaware of their existence deep within the cluttered confines. Amid the chaos, a few handy objects await discovery. However, trying to excavate them could cause a catastrophic avalanche. Trust me, I possess such a cupboard.

This scenario aptly represents a typical on-premises data center, a labyrinth of applications without discernment of their significance.

In the quest for cloud benefits, companies were urged to execute a “lift and shift” strategy—moving their existing applications to the cloud wholesale. This strategy often feels akin to relocating your cluttered cupboard into a rented garage in another part of town. You still grapple with the same amount of stuff; it’s just more inconvenient to access and secure. Not to mention, the garage comes with an additional rental cost.

An alternative to “lift and shift,” companies were also recommended to “containerize” their applications before cloud migration. Using the cupboard analogy, this would equate to packing your belongings into plastic crates before moving them to the garage. Containerization simplifies the transportation and management of applications and facilitates future moves between different storage units. Nonetheless, it inherits the downsides of garage storage, along with the added expense of containers. This “move and improve” strategy seems appealing, but the motivation to sort out the clutter often dwindles once it’s out of sight.

The Pitfalls of an Unplanned Journey

The ideal scenario involves decluttering the cupboard entirely. Broken items should be repaired or discarded, obsolete belongings removed, and duplicated or unused possessions donated. Following Marie Kondo’s mantra, you should retain only the items that “spark joy.” Once this selection is complete, you can consider whether to display these cherished items prominently or store them away, neatly and securely.

In the realm of cloud technology, this approach translates into cloud modernization: a comprehensive review and restructuring of applications for optimal cloud performance. This topic, however, lies beyond the scope of this book. As many companies have discovered, cloud modernization can be a lengthy and costly process. Many firms have resorted to the lift and shift or containerization strategies, only to find their applications harder to manage and secure and more expensive to run in the cloud.

Less than optimal experiences with cloud migration have resulted in scepticism and disappointment surrounding the cloud. Companies have been reminded that there is no one-size-fits-all solution or quick fix. Despite this disillusionment, digital native competitors continue to leverage the cloud’s advantages, warranting a deeper exploration into what sets these companies apart in their cloud strategy.

More Than Just an Online Data Center

Digital natives understand that the real power of public cloud services lies in their massive, globally distributed, shared, and highly automated data centers. These features enable the provision of pay-per-use billing, virtually limitless scalability, and a self-service consumption model, as shown in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. Cloud benefits

Nevertheless, public clouds are constructed from commodity hardware connected by networks that have been selected to minimize the total cost of ownership. The hardware is managed by a third-party provider and shared among multiple clients. It’s crucial to understand that cloud computing isn’t inherently more reliable, cost-effective, or secure than running your own data center:

-

Data center hardware is often built for redundancy and task-specific optimization, while in the cloud, hardware is generic, commoditized, and designed with the expectation of occasional failure.

-

In a data center, you own the hardware and change is difficult. In contrast, the cloud provides rented hardware on a minute-to-minute basis, allowing for easy change, but at a premium over your hardware.

-

A physical data center has an effective wall around it, engendering a level of implicit trust in the infrastructure inside. In the cloud, however, a trust nothing approach should be adopted.

Transitioning to the cloud isn’t simply a matter of transferring your traditional data center operations online. It represents an opportunity to leverage a powerful technology that can fundamentally reshape business operations. However, this requires the correct approach. Simply replicating your on-premises setup in the cloud without adapting your methods can lead to higher costs, heightened security risks, and potentially reduced reliability, as shown in Figure 1-3. This fails to utilize the full potential of the cloud and can be counterproductive.

Figure 1-3. The reality of treating cloud as another data center

Instead, acknowledging the unique characteristics and requirements of the cloud and fully embracing these can be truly transformative. Harnessing the elasticity, scalability, and advanced security features of the cloud can lead to levels of operational efficiency, cost-effectiveness, and innovation that surpass what traditional data center environments can offer.

The cloud isn’t just an online variant of your current data center. It’s a different paradigm that demands a different approach. When navigated adeptly, it can unlock a world of opportunities far surpassing those offered by traditional infrastructure. Embrace the differences, and the cloud’s full potential is vast.

Embracing the Cloud as a Distributed System

The essential truth of the cloud is that it functions as a distributed system. This key characteristic renders many assumptions inherent in traditional development obsolete.

These misconceptions, dubbed the fallacies of distributed computing, were first identified by L Peter Deutsch and colleagues at Sun Microsystems:

-

The network is reliable.

-

Latency is zero.

-

Bandwidth is infinite.

-

The network is secure.

-

Topology doesn’t change.

-

There is one administrator.

-

Transport cost is zero.

-

The network is homogeneous.

Each of these points represents a hurdle that must be surmounted when attempting to construct a cloud from scratch. Thankfully, cloud providers have devoted substantial engineering resources over the past two decades to build higher-level abstractions through APIs, effectively addressing these issues. This is precisely why digital natives have an edge—they are attuned to cloud native development, a methodology that leverages this groundwork.

Cloud native development acknowledges the distinct characteristics of the cloud and capitalizes on the high-level abstractions provided by cloud provider APIs. It’s a development style in tune with the realities of the cloud, embracing its idiosyncrasies and leveraging them to their full potential.

Distinguishing Cloud Hosted from Cloud Native

Understanding the difference between cloud hosted and cloud native applications is fundamental. To put it simply, the former is about where, and the latter is about how.

Applications can be cloud hosted, running on infrastructure provided by a public cloud provider, but architectured traditionally, as if they were operating in an on-premises data center. Conversely, applications can be designed in a cloud native manner and still be hosted in an on-premises data center, as shown in Figure 1-4.

Figure 1-4. Cloud hosted is where, cloud native is how

When I refer to cloud native, I am discussing the development style, application architecture, and abstraction provided by the cloud APIs, rather than the hosting location.

This book primarily explores the construction of cloud native applications using Google Cloud, which embraces both cloud hosted and cloud native principles, the bottom right in Figure 1-4. However, keep in mind that much of the information shared here is also applicable to on-premises private and hybrid clouds, particularly those built around containers and Kubernetes, such as Red Hat OpenShift, VMWare Tanzu and Google Anthos, bottom left in Figure 1-4.

Unraveling the Concept of Cloud Native

The term “cloud native” used to make me cringe, as I felt its significance had been diluted by software vendors leveraging it merely as a stamp of approval to signify their applications are cloud compatible and modern. It reminded me of other buzzwords such as “agile” or “DevOps,"” which have been reshaped over time by companies with something to sell.

Nevertheless, the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF), a Linux Foundation project established to bolster the tech industry’s efforts toward advancing cloud native technologies, provides a concise definition:

Cloud native technologies empower organizations to build and run scalable applications in modern, dynamic environments such as public, private, and hybrid clouds. Containers, service meshes, microservices, immutable infrastructure, and declarative APIs exemplify this approach.

These techniques enable loosely coupled systems that are resilient, manageable, and observable. Combined with robust automation, they allow engineers to make high-impact changes frequently and predictably with minimal toil.

In my early advocacy for cloud native technology, I commonly characterized it as encompassing microservices, containers, automation, and orchestration. However, this was a misstep; while these are vital components of a cloud native solution, they are just the technological aspects referenced in the first part of CNCF’s definition. Mistaking cloud native as purely a technological shift is one of the key reasons why many cloud native initiatives fail.

Introducing technologies like Kubernetes can be quite disruptive due to the steep learning curve and the added complexity they present to developers. If developers are merely handed a Kubernetes cluster and expected to manage it, problems are bound to arise. A common misconception is that cloud native begins and ends with containers or Kubernetes, but this is far from the truth.

There are also issues related to cost and security. Both these aspects undergo significant changes with the cloud, especially in a cloud native scenario. Developers need to work within appropriate boundaries to prevent costly mistakes or security breaches that could compromise an organization’s reputation.

What’s more crucial in the CNCF definition is the second part—the techniques. These reflect a development style that capitalizes on the cloud’s strengths while recognizing its limitations.

Cloud native is about acknowledging that hardware will fail, networks can be unreliable, and user demand will fluctuate. Moreover, modern applications need to continuously adapt to user requirements and should, therefore, be designed with this flexibility in mind. The concept of cloud native extends to considering the cloud’s limitations as much as utilizing its benefits.

Embracing cloud native means a mental shift toward designing applications to make the most of the abstractions exposed by cloud providers’ APIs. This implies a transition from thinking in terms of hardware elements such as servers, disks, and networks to higher abstractions like units of compute, storage, and bandwidth.

Importantly, cloud native is geared toward addressing key issues:

-

Developing applications that are easy to modify

-

Creating applications that are more efficient and reliable than the infrastructure they run on

-

Establishing security measures that are based on a zero-trust model

The ultimate goal of cloud native is to achieve short feedback cycles, zero downtime, and robust security.

So, “cloud native” no longer makes me cringe; it encapsulates and communicates a style of development that overcomes the cloud’s limitations and unlocks its full potential.

In essence, cloud native acts as a catalyst, making the initial promise of cloud computing achievable: accelerated development, cost savings, and enhanced capabilities.

Embracing Cloud Native Architecture

Cloud native architecture adopts a set of guiding principles designed to exploit the strengths and bypass the limitations of the cloud. In contrast to traditional architecture, which treated changes, failures, and security threats as exceptions, cloud native architecture anticipates them as inevitable norms.

The key concepts in Figure 1-5 underpin cloud native architecture.

Figure 1-5. Cloud native architecture principles

Let’s explore each of these concepts:

- Component independence

-

An architecture is loosely coupled when its individual system components are designed and changed independently. This arrangement allows different teams to develop separate components without delays caused by interdependencies. When deployed, components can be scaled individually. Should a component fail, the overall system remains functional.

- Built-in resilience

-

A resilient system operates seamlessly and recovers automatically amidst underlying infrastructure changes or individual component failures. Cloud native systems are inherently designed to accommodate failure. This resilience may be achieved through running multiple instances of a component, automatic recovery of failed components, or a combination of both strategies.

- Transparent observability

-

Given that a cloud native system encompasses multiple components, understanding system behavior and debugging issues can be complex. It is therefore crucial that the system is designed to allow a clear understanding of its state from its external outputs. This observability can be facilitated through comprehensive logging, detailed metrics, effective visualization tools, and proactive alert systems.

- Declarative management

-

In a cloud native environment, the underlying hardware is managed by someone else, with layers of abstraction built on top to simplify operations. Cloud native systems prefer a declarative approach to management, prioritizing the desired outcome (what) over the specific steps to achieve it (how). This management style allows developers to focus more on addressing business challenges.

- Zero-trust security

-

Given that everything on the public cloud is shared, a default stance of zero trust is essential. Cloud native systems encrypt data both at rest and in transit and rigorously verify every interaction between components.

As I explore these principles in later chapters, I will examine how various tools, technologies, and techniques can facilitate these concepts.

Building a Cloud Native Platform

Cloud providers offer a broad range of tools and technologies. For cloud native architecture to flourish, it is crucial to synergize these tools and apply them using cloud native techniques. This approach will lay the foundation for a platform conducive to efficient cloud native application development.

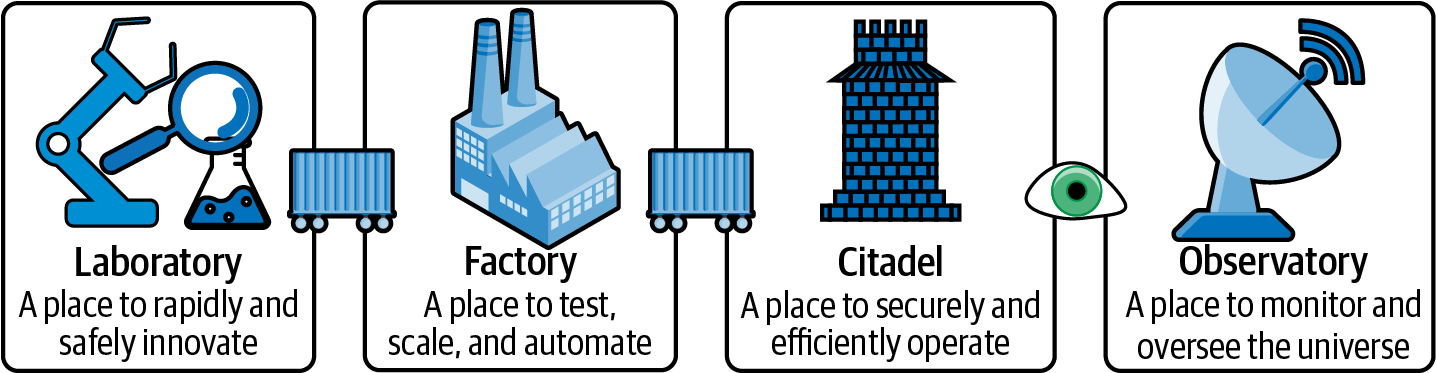

Laboratory, Factory, Citadel, and Observatory

When conceptualizing a cloud native platform, envision the construction of four key “facilities” on top of the cloud: the laboratory, factory, citadel, and observatory, as shown in Figure 1-6. Each one serves a specific purpose to promote productivity, efficiency, and security:

- Laboratory

-

The laboratory maximizes developer productivity by providing a friction-free environment equipped with the necessary tools and resources for application innovation and development. It should foster a safe environment conducive to experimentation and rapid feedback.

- Factory

-

The factory prioritizes efficiency. It processes the application—originally created in the laboratory—through various stages of assembly and rigorous testing. The output is a secure, scalable, and low-maintenance application ready for deployment.

- Citadel

-

The citadel is a fortified environment designed to run the application securely and effectively, protecting it from potential attacks.

- Observatory

-

The observatory serves as the oversight hub for all services and applications running in the cloud.

Figure 1-6. Developing effective cloud facilities

Ensuring a smooth transition of applications from the laboratory, through the factory, and into the citadel is critical. The same immutable code should be automatically transported between different facilities.

The Need for More Than Just a Factory

During the 90s, when I was thinking about what to study at university, I found inspiration in an episode of the BBC TV program Troubleshooter. The imposing Sir John Harvey-Jones visited the struggling classic car company, Morgan, suggesting they replace their outdated manufacturing methods with a modern factory to enhance production and product consistency. From then on, I was captivated by the idea of improving companies’ efficiency.

Yet, a decade later, a follow-up episode revealed that Morgan had defied Sir John’s advice entirely, instead capitalizing on their unique craftsmanship as a selling point. Remarkably, the TV program itself ended up promoting their craftsmanship and drawing new customers.

For many enterprises, the prospect of establishing a factory presents an enticing solution to streamline what is often perceived as the chaotic landscape of the cloud. As an engineer, I naturally gravitate toward such systematic order. However, confining and regulating development solely within an automated production line risks sacrificing innovation and craftsmanship, attributes that often set a product apart. A factory-only approach could undermine the creative freedom facilitated by the on-demand public cloud, which is skillfully exploited by digital natives.

To harness the cloud’s full potential, it’s not enough to have a factory for automating testing and ensuring quality consistency; a laboratory is equally crucial. In this space, developers can craft and rapidly innovate a product in a safe environment, with a wide array of tools at their disposal, before transitioning smoothly to the factory.

Once the factory has produced thoroughly tested and trusted applications, a third facility, the citadel, is necessary where the application can function securely in a production setting.

Summary

Cloud native represents an architectural approach and development methodology that fully exploits the potential of the cloud. It’s characterized by specific techniques, tools, and technologies designed to enhance the strengths and mitigate the weaknesses inherent in cloud computing. Importantly, the scope of cloud native isn’t confined to Google Cloud or even the public cloud. It encompasses a broad spectrum of methodologies applicable wherever cloudlike abstractions are present.

To thrive in the cloud native ecosystem, developers need to harness the potential of four distinct yet interdependent facilities: a laboratory for innovative exploration, a factory for streamlined production automation, a citadel for robust defense of live applications, and an observatory for comprehensive system oversight.

The remainder of this book will guide you through these cloud native methodologies, demonstrating how to create and optimize a laboratory, factory, citadel, and observatory using Google Cloud. The aim is to equip you with the knowledge and strategies that maximize your chances of achieving cloud native success. Before you embark on this journey, let’s first examine why Google Cloud, among others, offers a particularly conducive environment for cloud native development.

Get Cloud Native Development with Google Cloud now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.