Chapter 1. A Fascination with the Future

Before diving into process and methods, I typically like to introduce the concept of futuring (the activity of discussing, speculating, and trying to interpret the future) by looking at how we as humans have tried to interpret, predict, and manage future events for exploration or survival. This is both a way to deconstruct how future-tellers have operated throughout time and a metaphorical device for describing these innate abilities, as well as a way to compare futuring to other systems that we’ve designed for navigating uncertainty. Our species has always been fascinated with the future and with anything that could impact our fate on this planet, and for thousands of years we’ve looked to those who have been ordained with special gifts or skills to reveal their premonitions to us. In the distant past, prophets and soothsayers were futurists who were seen as fortune tellers—gifted individuals endowed with the gift of clairvoyance. Prophets could speak to the gods and had visions that could determine certain events. Though their methods weren’t necessarily based on what we would today consider scientific principles, these oracles were highly regarded as consultants and confidants to leaders or governments; they had the ability to explain certain phenomena or sway the tides of war or political decisions in a certain direction. Fundamentally, this was an early form of futuring, as these were people who used patterns (and sometimes interpretations of dreams and the imagination) to describe what they saw, which is not too dissimilar to what we do today.

But even before these specialized roles existed in society, we as individuals had been using various devices, models, maps, and stories to describe the future and the unknown. Whether we realize it or not, we are obsessed with the future, largely for reasons of survival, curiosity, and progress. We speculate about the future every day. Whether we’re thinking about a trip to the store, planning a vacation, mapping out a career path, or trying to figure out how humans might fly to Mars, forming conjectures about the future is an inherent ability; and those mechanisms are, in fact, the same kinds of tools we use in Futures Thinking (we just put different frameworks and labels around them). We absorb what we know about the world around us and make connections and assumptions about consequences so we can figure out how to attain our goals.

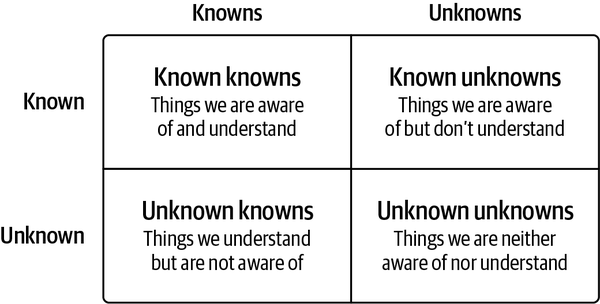

The world has recently survived a pandemic and continues to experience wars, economic crises, and the effects of climate change, and thus there has been renewed interest in futures and strategic thinking so that we can look at more societal, ethical, and globally impactful issues such as environmental crises and political instabilities. But there is still much that is uncertain. In 2002, US secretary of state Donald Rumsfeld, referring to the investigation into weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, said at a press conference that “there are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns—the ones we don’t know we don’t know.” This statement of possible unknowns eventually became known as the Rumsfeld Matrix1 (see Figure 1-1) and is an example of the different types of uncertainty that can exist.

Figure 1-1. The Rumsfeld Matrix

The Rumsfeld Matrix has four quadrants (Figure 1-2):

- Known knowns

-

These are facts or variables that we’re aware of and understand. They form the basis of our knowledge and provide a solid foundation for decision making.

- Known unknowns

-

These are factors we know exist but don’t fully understand. They represent gaps in our knowledge that we must address through research, investigation, or consultation with experts.

- Unknown knowns

-

These are elements that we don’t realize we know. They’re typically buried in our subconscious, overlooked, or dismissed as irrelevant. Uncovering these insights can lead to surprising breakthroughs in decision making.

- Unknown unknowns

-

These are factors that we’re not aware of and can’t predict. They represent the most significant source of uncertainty and risk, as they can catch us off guard and derail our plans.

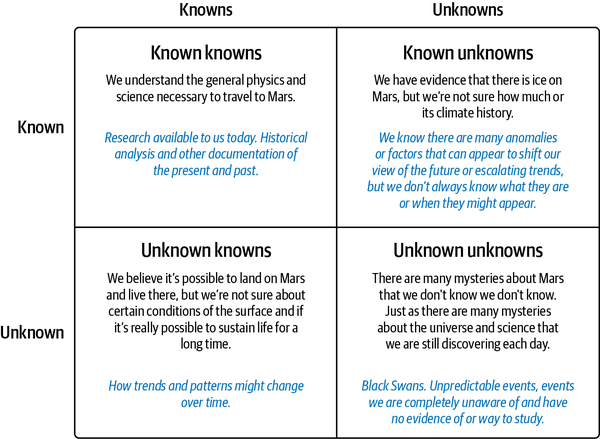

Figure 1-2. An example of a Rumsfeld Matrix regarding travel to and colonization of Mars

Even with all the sensors, data, and algorithms we use to try to understand the future, there are always unknowns, and there will always be some level of speculation. However, speculation, which is a facet of futuring, doesn’t have to be a wild guess without boundaries or evidence. The word itself seems to suggest something that could be unreliable or unbelievable. But we speculate about things every day; some things we have a little more evidence to speculate about than others, but essentially there are always some levels of uncertainty. And even defining those types of uncertainty based on what we know is still somewhat of a guess. But we continue to do it anyway.

If you are going to walk to the store and the weather report says it’s going to be cloudy, it might be so. But it could also rain. And potentially the weather predictions don’t account for the small pocket of rain that just might interrupt your path to the store (places like New York and San Francisco have microclimates that are quite unpredictable). The rain is an uncertainty you may or may not have planned for, but you go out anyway. If you are caught in the rain without an umbrella, you get wet. If you thought about that uncertainty and brought an umbrella, you stay dry. Our path into the future is similar. We have to set sail into it because we have a mission to get somewhere. It might rain on us, or it might not. We can try to be prepared by bringing an umbrella in the event that that uncertainty comes true. But this also requires a belief system and ultimately a leap of faith. But then you might ask: if there are so many uncertainties, why do we even bother trying to understand the future? We could ask the same question of our ancestors. Humans, like all animals, exist in complex, volatile, and uncertain environments, and we must rely on our senses and an ability to comprehend and predict patterns around us so that we can successfully navigate the world and the future. This is one of the fundamental concepts of Futures Thinking.

Fail we may, sail we must—Dan Levy, an innovation and design leader, and founder and principal of More Space for Light, has this statement immortalized in a tattoo on his arm. It serves to remind him of his purpose in his work and in all aspects of his life. Failure in business and in life is unavoidable. The only way to make progress is to accept this as a fact and keep moving forward. Levy helps his clients embrace this attitude for strategizing on new and potential futures.

In this chapter I’ll walk through several examples of how humans have tried to predict and imagine the future—from our early cave-dwelling ancestors to the science fiction writers and filmmakers of today. I’ll also discuss some analogies for how futuring is really just a system of mapping out the world around us and ahead of us, a way to safely navigate through time and space, and a way to strategize about consequences and implications (both positive and negative). By connecting history and the natural inclinations that we use to think about the world, we can use these same analogies to make it easier for others to comprehend the process and ultimately use that information to design the future.

Survival of the Fittest

As one of many species trying to survive and evolve on the planet, humans have found numerous ways, whether through images or storytelling, to document the past and present as a method of recordkeeping for future generations. Some of what our ancestors memorialized in caves or in ancient buildings was left behind intentionally as a guideline for survival; some of it they created merely to capture life as it unfolded around them. Some of the earliest records of these observations go back more than 17,000 years with the paintings found in the caves of Lascaux (Figure 1-3). Though it’s difficult to truly explain the meaning of some of the images, some theorize that they are a documentation of past hunting successes, or that they could be tied to rituals or stories to be passed on to future generations as cautionary tales, or as strategic planning, or to invoke wonder at and appreciation for the beauty and dangers presented by the world.

Essentially, these were images that the artists reproduced from common patterns in their environment. The logic of observing and predicting those patterns came with a necessity to feed, migrate, or teach. But we aren’t the only animal that observes patterns to anticipate the future. In 2004, flamingos, elephants, and cats in Japan were seen behaving erratically and trying to quickly migrate to higher ground. This behavior was observed and recorded as many as six days before a magnitude 9 earthquake hit off the coast of northern Sumatra and sent a massive tsunami onto the shores of over a dozen countries, killing more than 225,000 people. Scientists believe that certain animals have incredibly acute senses that might enable them to hear or feel the earth’s vibrations, tipping them off to approaching disaster long before humans realize what’s going on. While these animals aren’t necessarily reading market trends, they are using their natural sensors to listen to signals of changes in the environment. Sensing changes in the vibrations of the earth is no different than monitoring “vibrations” in the stock market. With the help of artificial intelligence, we will soon be able to develop acute senses about the world around us. With inputs coming from multiple sources (social media, videos, news), it is possible that AI will be able to accurately predict the future as well as give us suggestions about what to do should certain scenarios materialize. With the advent of nanotech, wearables, and other devices that can connect our bodies and brains to this kind of intelligence, we could become a new type of tech-enabled fortune tellers.

Figure 1-3. Cave paintings of Lascaux, France (source: subarcticmike)

Meteorology

There are Indian manuscripts from as far back as 6000 BC that tried to predict the weather by observing cloud formations. The ancient Greek philosopher Thales of Miletus has been called the world’s first meteorologist; he is said to have predicted the weather and a solar eclipse. And though the weather was sometimes attributed to the work of the gods, some used simple observation and documentation of patterns and commonalities they saw as a logical formula for predicting the weather. This eventually led to what we now call atmospheric sciences, a critical field that many agencies (such as those in aviation and the airlines industry) use every day to plan out any journey on the planet. Today’s modern weather forecasting relies on an intricate and orchestrated array of sensors, satellites, and redundancies that come together to analyze and predict what the weather might do. I say might because, even with all the satellites and algorithms we’ve developed, we still are not as accurate and precise as we would like to be at times. Natural disasters such as hurricanes and floods still occur, devastating whole regions, and even after they arrive, we are still guessing where, when, and how they might transform or happen again. Many attempts are being made to try and manipulate the weather through geoengineering, an approach that involves projects such as seeding clouds with additives to increase rain or snow, or blocking the sun to reduce harmful radiation from space. But no matter how much we try to predict or control weather events, there is always a force much stronger and more unpredictable than what humans have the ability to control (the unknown unknowns). It’s much the same with trying to predict the future. Our instruments can see only so far ahead, and the further into the future we try to look, the blurrier and more uncertain it can be. We can hope and pray that we are right, but we will never be able to fully control certain events or how our actions will impact the emergence or transformation of certain events. Yet we still try, and that is also a fundamental principle of thinking about the future: no matter what the data says (good or bad), we still must try to understand it to avoid certain risks or facilitate certain opportunities.

Mapping the Unknown

Conceptually, maps have always been more than navigation devices; they’re a way for us to find our way in the dark, avoid obstacles, and find safe passage to our destination. They have served as both a documentation of landscapes and a tool for current and future generations to move about safely and trade or transport food and materials. But due to the limitations of technologies through the eras, there have always been uncharted territories that we have been forced to speculate about. Even today, with all our fine instrumentation, there is still much of the galaxy (not to mention the universe) that we know nothing about, and we have to use triangulations of data to understand what is out there and how we might survive were we ever to travel beyond the earth’s moon. I like to think about futuring as if we are drawing a map into the unknown. There’s information that we know to be true (known knowns) and that will continue to be true based on evidence, and there’s information that we have to speculate about (known unknowns, unknown unknowns). Drawing a map allows us to identify obstacles and channels that we want to travel within, explore, or avoid completely.

Some of the earliest maps were based purely on memory and personal accounts as well as on mythologies derived from spiritual or religious stories. The oldest known map, the Babylonian Imago Mundi, is a map of the Mesopotamian world that dates back to the sixth century BC (Figure 1-4). Consisting of simple geometric shapes with cuneiform inscriptions, it places Babylon, an ancient city once located in southern Iraq, in the center, surrounded by what seem to be mountains and bodies of water that likely represent the Euphrates River and the sea. The map is divided into eight regions, with descriptions such as “where a horned bull dwells and attacks the newcomer,” “where the morning dawns,” “where one sees nothing,” and “the sun is not visible.” Though parts of the original tablet map are missing, it gives us a peek into the vocabulary and stories that were used to describe unknown regions at the time and the cultural values that existed back then.

Figure 1-4. The Imago Mundi, from circa sixth century BC (source: Wikipedia)

Maps, much like futuring, are a way of understanding what is around us and where to go to avoid danger. As we began to explore and discover new parts of the world in the centuries after the creation of the Imago Mundi, we developed more advanced mapping techniques, eventually giving rise to modern cartography. In addition to personal accounts or drawings, the migration patterns of birds and animals as well as the locations of stars were used to triangulate and detail areas of the world. After the discovery of the Americas, Juan de la Cosa, a Spanish cartographer, explorer, and conquistador, created his Mappa Mundi in 1500; this was one of the first recorded maps to include the New World (Figure 1-5). Though there was still much that was unknown and undocumented about what lay on the other side of the planet, de la Cosa tried to fill in the gaps by interpreting what information he did have. On the right side of the map, much of Europe, Africa, and Asia are populated and detailed, while the left side is an inaccurate landmass devoid of much civilization but rich with green mountains and valleys. The accounts of explorers who had made it back from the New World became the only input to inform the map’s design. Sometimes, even today, we must rely on experts or other voices to fill in gaps about the future. We may not have empirical evidence to support certain ideas or assumptions, but we have to trust them and try to describe what the world could look like. The lack of precise data regarding a future occurrence has never stopped us from documenting what we think is out there and following it until we are proven wrong. And even then we are able to modify our understanding based on what we see occurring or changing in the world.

Figure 1-5. Map by Juan de la Cosa showing the Old World and the New World (1500)

In our heads we are constantly mapping out the future, thinking about different scenarios, and trying to predict what is ahead and how we might navigate turbulent waters or obstacles we encounter. (In Chapter 8 we’ll look at a method called the Futures Wheel, a diagramming tool used to map the implications of events, trends, or ideas that is, in turn, a way of mapping the future.) But even with a visual representation of the world around us, there are still many factors that could impede our journeys. In the past, a sailing voyage across the Atlantic could be riddled with uncertainty and unknowns, including the weather, human hardships, the complexities of engineering related to sailing large vessels, and even the unpredictable behavior of crews that had to endure such long journeys. To successfully traverse the ocean from east to west, much more planning had to be done, considering it could take several weeks or months just to reach a destination. Thus maps may give us a compass or directional guidance, but there are always uncertainties that we have to prepare for.

As we dive into the stages and activities of Futures Thinking, consider that you are on a fact-finding mission to create your map to a foreign land. The research we do will inform that map and will eventually be used to guide us into the future, avoid obstacles, and create a safe path for us to succeed. It won’t always be 100% accurate, but if we do the work, we can gain a much clearer understanding of where we want to go and what we want to do when we get there. But just like traditional maps, our maps of the future must be continuously updated as we receive more information over time.

Imagining the Future

Even some of the early religious prophets would use stories as a way to foretell future events. They were not only orators but also charismatic storytellers, because it was the drama and delivery of their stories that would help create the impact that would inspire or terrify those who sought information. Today, psychics and fortune tellers are seen more as entertainers and are known to use techniques to home in on the sensitivities and body language of audience members in order to pick up clues and deliver predictions about their lives. The story, in turn, is just as important as the future that it portrays. Neither magicians nor psychics have real “magical” abilities; instead, they have tactics for eliciting information by monitoring people’s responses to very specific questions or prompts. These become the signals that they interpret and generalize from to make their audience believe what they say is relative or true. I’m not saying that futurists are deception artists like psychics or magicians, but we do use certain methods to try to pick up on clues in the world and interpret what we want to know about the future. And we in turn transform that information into sometimes dramatic stories that can incite change or transformation. But part of our job is also to fill in the gaps. And some of those gaps are based on knowledge, experience, and or even pure assumption.

In a 2021 article in Wired, Amanda Rees wrote:

Since the earliest civilizations, the most important distinction in [how predictions were made and interpreted] has been between individuals who have an intrinsic gift or ability to predict the future, and systems that provide rules for calculating futures. The predictions of oracles, shamans, and prophets, for example, depended on the capacity of these individuals to access other planes of being and receive divine inspiration. Strategies of divination such as astrology, palmistry, numerology, and Tarot, however, depend on the practitioner’s mastery of a complex theoretical rule-based (and sometimes highly mathematical) system, and their ability to interpret and apply it to particular cases.

While words can be an effective way to depict a narrative about future worlds, they are always stronger when paired with a visual representation. Maps are visualizations of the physical world just as much as a graphic novel or comic book is a visualization of a fantasy world, or a designed prototype is a fragment of the future pulled into today. They are no different in function, except they differ in content, intent, and use. Any story, image, or experience about the future is essentially a diagram of that world wrapped inside a colorful frame. We can use such visual diagrams to place people into that world for a moment so that they can experience and react to what it might be like to live there. Just as we use film, literature, and comics to suspend reality so that we can journey into a different time and place, futures work can be much more effective when we illustrate that story (whether rendered statically in an image or distributed into a storyboard or a time-based medium such as film).

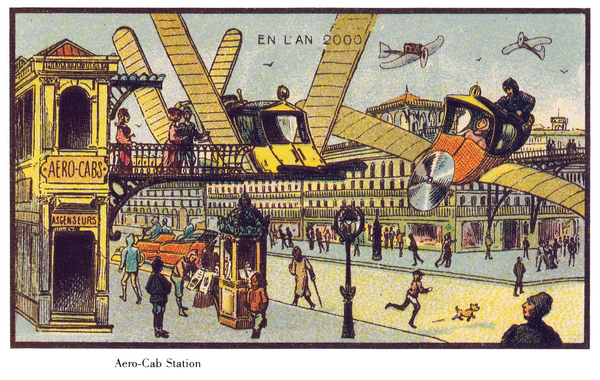

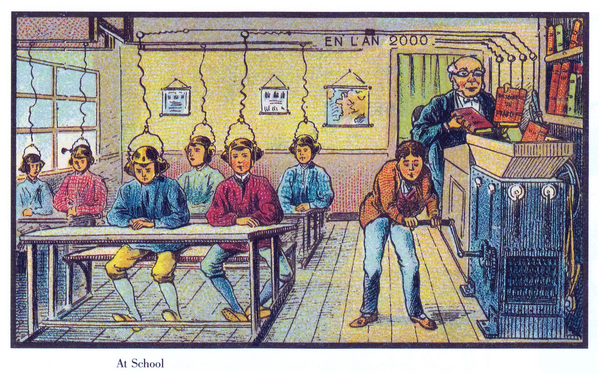

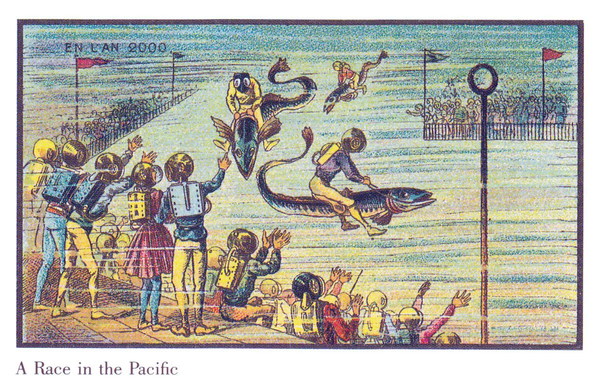

In the late 1800s, a French toymaker commissioned Jean-Marc Côté and several other artists to depict visions of the year 2000 (more than one hundred years into their future). Their illustrations (shown in Figures 1-6, 1-7, and 1-8), which originally were in the form of postcards and paper cards enclosed in cigarette and cigar boxes, were distributed between 1889 and 1910 and portrayed a variety of lifestyle scenes and technological advancements in transportation, communication, and sporting activities. The series included at least 87 unique cards. The cards were not made widely available at the time due to financial constraints, but the science fiction writer Isaac Asimov rediscovered them decades later and published them in a book titled Futuredays: A Nineteenth-Century Vision of the Year 2000 (Henry Holt).

Figure 1-6. Jean-Marc Côté illustration of flying cars in the year 2000

Figure 1-7. Jean-Marc Côté illustration of a school in the year 2000

Figure 1-8. Jean-Marc Côté illustration of an underwater race in the Pacific Ocean in the year 2000

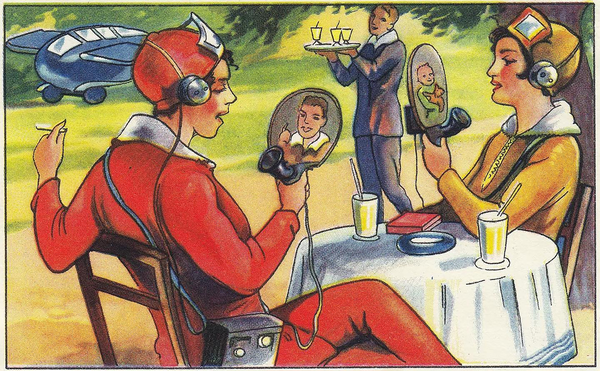

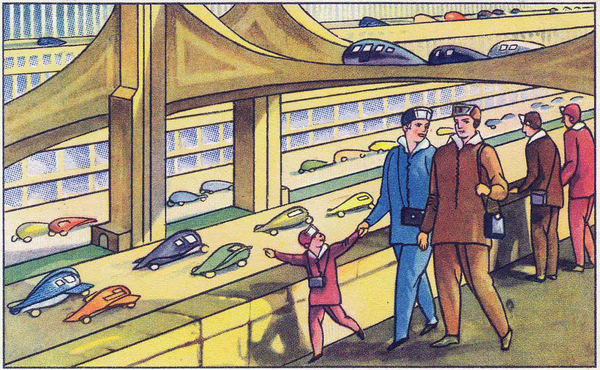

In 1930, Echte Wagner, a German margarine manufacturer, produced a line of card sets that were intended for collection in an album. The album included a section called Zukunftsfantasien (Imaginings of the Future). Unfortunately, no artists or authors are credited, but it depicts several scenes of future transportation innovations (see Figures 1-9 through 1-13). While these images illustrate several ideas that have yet to materialize, they also depict some concepts that did eventually become reality, such as wireless phones, televisions, and superhighways.

Figure 1-9. Cover of Echte Wagner Margarine Album Nr. 2

Figure 1-10. Echte Wagner, “Wireless Private Phone and Television.” Translation of the verso: “Each person has their own transmitter and receiver and can communicate with friends and relatives using certain wavelengths. But television technology has become so advanced that people can talk and watch their friends in real time. The transmitter and receiver are no longer bound to the location but are carried in a box the size of a photo apparatus.” (Source: Klaus Buergle, “Real Wagner Margarine” scrapbooks/Atomic Scout/verso adapted from the German by Otto Z. Mann.)

Figure 1-11. Echte Wagner, “New Highways.” Translation of the verso: “The horses are gone, and electricity has replaced the steam power. The pedestrians are no longer in danger from traffic because the motorways and sidewalks are strictly separated. All men and women wear uniform clothing: zipped suits and pants.” (Source: Klaus Buergle, “Real Wagner Margarine” scrapbooks/Atomic Scout/verso adapted from the German by Otto Z. Mann.)

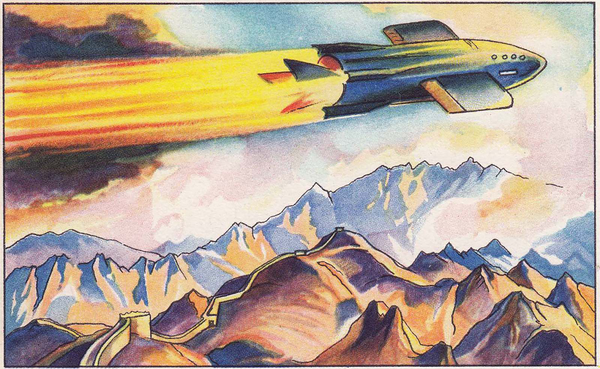

Figure 1-12. Echte Wagner, “The Rocket Plane.” Translation of the verso: “The aircraft of the future is powered by rockets. The rockets are fitted at the stern of the vessel, which propels the aircraft forward through the recoil of the escaping gases. The aircraft shown here is cruising toward Nankoupas and the ancient Great Wall of China with 10,000 kilograms of mail. Since it has a speed of 1,000 km per hour, it takes less than 8 hours for the Berlin–Tokyo route. A steamer today needs about 50 days!” (Source: Klaus Buergle, “Real Wagner Margarine” scrapbooks/Atomic Scout/verso adapted from German by Otto Z. Mann.)

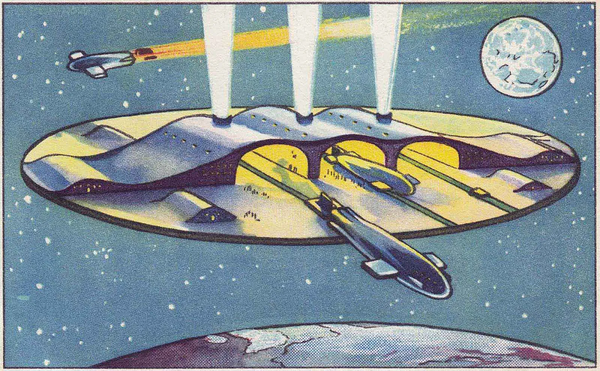

Figure 1-13. Echte Wagner, “Spaceship Port.” Translation of the verso: “Because there are rare minerals on the Moon, America has built a $20 billion enterprise named MoMA-A.G. (Moon Minerals A.G.). At this dock station, the ships can renew their rocket fuel. The station floats freely in space.” (Source: Klaus Buergle, “Real Wagner Margarine” scrapbooks/Atomic Scout/verso adapted from German by Otto Z. Mann.)

In these frozen frames of future worlds, a sequential story is not necessarily being told, but in each image is embedded an implicit narrative about what could be, given certain advancements. The artists took scenes of their current reality and transported them into a new one augmented with innovations that provoke new ideas about where we could go if we had the ability. These “visions” may not have been the work of trained prophets or scientists with special abilities, but they are an amalgamation of the artists’ own imaginations, dreams, and observations about the world around them, including what they were exposed to and inspired by at the time.

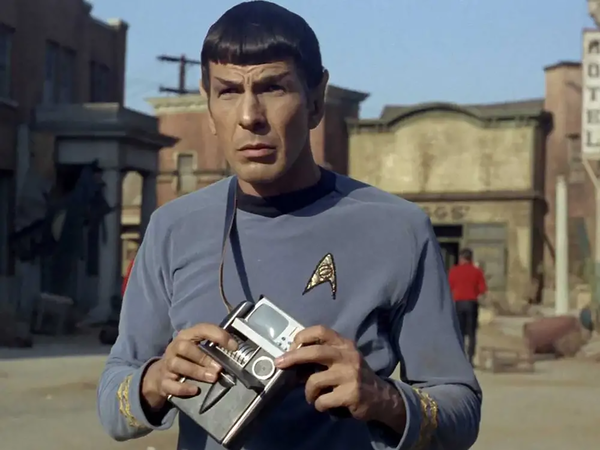

Literature, film, and television have always played a major role in entertainment and inspiration when it comes to imagining future worlds. From the 1960s television series Star Trek to Star Wars and beyond, imaginations have run wild, mixing fantasy and science fiction to explore new territories. Star Trek’s stories take place in 2265 and follow the journey of the starship USS Enterprise as its crew discovers new planets and life forms and navigates both military and ethical conflicts. The first episode, which debuted in 1966, introduced many concepts into science fiction that would become inspiration for real technologies to come. One of those concepts/devices was the tricorder (Figures 1-14 and 1-15). The show’s creator, Gene Roddenberry, described this device in the series’ Writers/Directors Guide:2

TRICORDER: A portable sensor-computer-recorder, about the size of a large rectangular handbag, carried by an over-the-shoulder strap. A remarkable miniaturized device, it can be used to analyze and keep records of almost any type of data on planet surfaces, plus sensing or identifying various objects. It can also give the age of an artifact, the composition of alien life, and so on. The tricorder can be carried by Uhura (as communications officer, she often maintains records of what is going on), by the female yeoman in a story, or by Mister Spock, of course, as a portable scientific tool. It can also be identified as a “medical tricorder” and carried by Dr. McCoy.

Figure 1-14. Mr. Spock holds a tricorder in the 1966 Star Trek episode “The Man Trap”

Figure 1-15. An original sketch of the first tricorder designed by Wah Ming Chang for Star Trek (left), and a prototype used in the series (right)

The concept of a portable scanning device that can capture a variety of data inspired the Canadian company Vital Technologies Corporation to develop and produce the first “real world” tricorder in 1996. The scanner was called the TR-107 Mark 1 (Figure 1-16), and it could scan and measure electromagnetic radiation, temperature, and barometric pressure. Vital Technologies sold ten thousand of the devices before going out of business in 1997.

Figure 1-16. Vital Technologies’ TR-107 Mark 1 tricorder

In the decades since the show’s inception, Star Trek has inspired millions of people with its stories that detail the trials and tribulations of exploring unknown worlds while highlighting challenges similar to those we face here on earth with regard to politics, cultures, ethics, and war. And the dream of creating a modern-day tricorder, or a device that can measure many vital statistics about an environment or a human, continues to the present day. Today, the modern Apple Watch can measure everything from your blood pressure to the timing and strength of the electrical signals of your heart, providing doctors with insight about potential heart irregularities and conditions. In January 2024, at the annual Consumer Electronics Show in Las Vegas, the health tech company Withings debuted a new product called the BeamO that combines four medical tools: a stethoscope, an oximeter, a one-lead ECG, and a thermometer (Figure 1-17).

Figure 1-17. The Withings BeamO, a four-in-one at-home vitals monitor that can measure body temperature and blood oxygen levels and that also features a digital stethoscope and a medical-grade ECG2

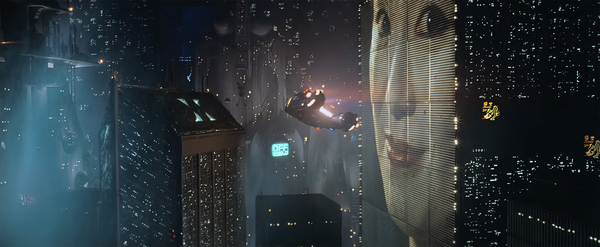

However, some of the storytelling devices in science fiction are inherently used to create drama and conflict in order to keep readers’ attention and create a feeling of excitement or dread around the possibilities of what technology and society could become. Dystopian tales of collapsing societies and of unchecked and uncontrollable technologies are common themes in the sci-fi portfolios of literature and film. Not all science fiction stories are dystopic, however; sci-fi has also been used to explore the optimistic potential of society, envisioning futuristic technologies and the benefits they could have for mankind. Philip K. Dick, who wrote dozens of novels and more than 120 short stories, was a popular science fiction author whose stories have been turned into feature films such as Blade Runner, Total Recall, and Minority Report. Many of his stories were huge successes and inspired countless other science and science fiction authors. The movie Blade Runner (Figure 1-18), adapted from his novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, is a dark vision of a polluted and overpopulated Los Angeles in the year 2019, when the world is populated with genetically bioengineered “replicants” (androids) that are visually indistinguishable from humans. The story focuses on an android-hunting detective named Rick Deckard, who reluctantly agrees to take one last assignment to hunt down a group of recently escaped replicants. During his investigations, Deckard meets Rachael, an advanced experimental replicant who causes him to question his attitude toward replicants and what it means to be human. Laden with flying cars, robots, and futuristic devices, homes, and cityscapes, Blade Runner has become a common reference point for anyone contemplating dystopian futures and the potential consequences of artificial intelligence gone astray.

Figure 1-18. The Los Angeles skyline in 2019, as envisioned in the 1982 film Blade Runner

Around 1993, Glen Kaiser, a former product manager at AT&T, a major telecommunications company in the United States, teamed up with David Fincher (later the director of such films as Fight Club and The Social Network) to develop a marketing campaign and series of television commercials titled “You Will”. They created several commercials (Figures 1-19 through 1-22) that showcased emerging technologies and platforms being developed at Bell Labs and AT&T at the time. The narration for the first ad, delivered by Tom Selleck, began, “Have you ever borrowed a book from thousands of miles away? Crossed the country without stopping for directions? Or sent someone a fax from the beach? You will. And the company that will bring it to you is AT&T.” In an interview on Quora, Kaiser explained the history behind the campaign:

A young team of six people, including me, were charged with developing leading-edge new business services (as opposed to consumer services). I was Product Manager for the Picturephone Meeting Service, one of the key areas where we saw AT&T having a dominant future. We at Corporate did all the research in specific markets of video conferencing, voicemail, messaging, security, and even RFID tracking. Financial business cases were developed, and the labs were funded to build the products and services. It was akin to being at Xerox PARC or at Palo Alto Research Park. I visited all of them. We were well on our way to making these applications commercial using the latest Bell Labs research and technology.

In the mid-eighties, AT&T was offered the chance to sponsor Spaceship Earth at Disney’s EPCOT Center, showcasing some of our applications. When it launched, EPCOT demonstrated the appeal of AT&T’s technology vision. Millions of visitors saw it and were excited by its near-term realization.

By 1993, the products we had in mind were not quite ready for prime time—the quality they needed to be at for widespread market adoption was not there yet, and affordability would also have been a factor. But in reality, the concepts were good, the core technology was real, and we just needed to wait for Moore’s law and Internet adoption to catch up for us to properly commercialize them....

The aim of this advertising initiative was clear: To project a more relevant AT&T to the youth demographic, and build enthusiasm for what we had in the pipeline. We picked all of the applications and technology that we thought were both realistic and would create interest for consumers.

Figure 1-19. Image from a 1993 AT&T “You Will” commercial portraying smart home capabilities

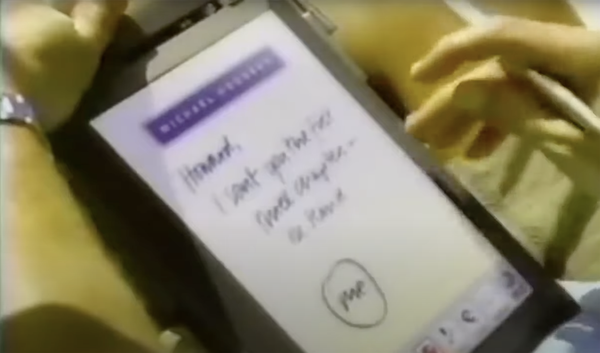

Figure 1-20. Image from a 1993 AT&T “You Will” commercial that envisions writing on a digital tablet at the beach

Figure 1-21. Image from a 1993 AT&T “You Will” commercial that portrays a student at their desk listening to a teacher through a remote interface

Figure 1-22. Image from a 1993 AT&T “You Will” commercial showing a child using the interface of a smart TV

The campaign, which showcased many technologies that eventually became a reality, seemed at times to accurately predict the future with great precision. Among the ideas depicted in the short vignettes were innovations such as smart homes, digital tablets, remote work, telelearning, radio frequency identification (RFID), smart tolls, digital medical records, and smartwatches.

In December 2011, Charlie Brooker launched a TV series in the United Kingdom called Black Mirror. Each episode has a different plot, actors, theme, and message and is set in a near-future dystopia, usually focusing on the use and implications of fictional technology. The series is inspired by The Twilight Zone and uses the themes of technology and media to comment on contemporary social issues. Black Mirror has received critical acclaim for its provocative messages about how we are engaged with technology today, how our culture is changing and potentially threatened by the various consequences of tech, politics, and the impact on the human condition. The show’s pilot episode, “The National Anthem,” did not feature futuristic sci-fi tech, however; instead, it was a commentary on how society consumes and dramatizes news, information, and politics as entertainment, perpetually fueling a machine of drama and exposing people’s lives for political influence and to increase ratings, all at the cost of others’ personal tragedies. The episode titled “San Junipero” (Figure 1-23), released in 2016, is a love story set in a future in which people can upload their consciousnesses into a virtual world inhabited by the deceased and the elderly. The episode touches on several trends and technologies that were developed or became more widespread during the 2010s: same-sex relationships, virtual reality, online community platforms (early metaverse), and society’s obsession with controlling the aging process, as well as digital afterlife.3 The story is a testament to the potential of technology to assist in euthanasia and the consideration of ethical concerns, as well as a platform for exposing the underlying taboos around same-sex relationships, as these communities have continued to fight for equal rights and representation in film, media, and society.

The story synopsis goes like this:4

In 1987, the shy Yorkie meets the outgoing Kelly in a beach resort town named San Junipero. The next week, the pair meet again and have sex. Yorkie struggles to find Kelly afterwards, until a man suggests looking in a different time. She searches in multiple decades until finding Kelly in 2002, where Kelly confesses that she is dying, and wanted to avoid developing feelings for Yorkie. They have sex again. San Junipero is revealed as a simulated reality inhabited by the deceased and the elderly, who interact through their younger bodies. In California, Kelly meets a paralyzed Yorkie, soon to be euthanized so that she can live in San Junipero permanently. Kelly marries Yorkie to authorize the euthanasia. However, the pair argue when Kelly says she does not wish to stay in San Junipero when she dies: her husband, with whom she was together for 49 years, did not choose to join after their daughter died without the option to do so. After some time, Kelly changes her mind and happily reunites with Yorkie after her own euthanasia.

Reviewers have described “San Junipero” as a highly optimistic, emotionally rooted love story and a work of science fiction. It features the first same-sex couple in Black Mirror. Rebecca Nicholson of The Guardian wrote that it “leaves you believing in the power of love to fight pain and loneliness.” Some reviewers noted that the love story “transcends consciousness.” The episode also has unhappy elements and has been called “bittersweet.”

Figure 1-23. A scene from the Black Mirror episode “San Junipero”: Kelly and Yorkie having a drink at Tucker’s

In March 2020, the director Alex Garland released a limited series called DEVS on the FX network. (Spoilers ahead!) The series, a science fiction thriller starring Nick Offerman and Sonoya Mizuno, is based around a fictional company called Amaya that eerily echoes tech giants like Google or Facebook. Situated in an area that resembles Silicon Valley, Amaya is a quantum computing giant that has seemingly cornered the market with its technologies (Figure 1-24).5 But hidden within a bunker in the Amaya compound is a very secretive, highly secure project called DEVS that is protected by a Faraday cage and that only selected elite engineers are allowed to work on. The series centers on the disappearance of an engineer’s boyfriend shortly after he begins work on the project. As the engineer (Mizuno) delves deeper into what DEVS really is, she discovers that not only has Amaya been using its quantum technology to predict certain events in the world, but it also has the ability to look back in time thousands of years. The proposition of DEVS speaks to much of the cultural fascination and mystery around what quantum computers are capable of. Today only a few companies in the world—Google, IBM, and Microsoft, for example—have quantum computers, and they are being used in the areas of physics, communications, and other mathematical problems that have been deemed too costly or difficult for classical computers to solve. But the promise of quantum is just on the horizon. DEVS is a speculation on what we could do with quantum if we had the power to apply it to predicting the future and seeing deep into the past. What are the implications? And how could it change the way we view or navigate the world if the future could be predetermined by a machine? Where does human agency ultimately play a part? But also, what are the dangers associated with wielding such power, and what ethical concerns could arise?

Figure 1-24. Quantum computer in the FX series DEVS (photo by Miya Mizuno/FX)

Whether in static images or in the moving images of film and TV, the future has always been illustrated in different formats to draw us into possible worlds so that we can either internally or externally participate in a discourse around “What if?” questions. The statements embedded in some of these examples may vary based on the authors’ intended commentary or the era the authors were living in, but they were all created to serve the purpose of describing the future with a sense of wonder and excitement, as well as with caution and deliberation. Not all of these visions came true, but some certainly did. The intent is not to be accurate or correct, but to use them as a platform to fuel discourse, imagination, transformation, and innovation. As technology, media, and the connections of global communities expand, contract, and evolve, there are more opportunities every day to inspire people about the future through storytelling, using simple devices of narratives, visualizations, and drama. One thing is certain, however: we will have no shortage of visions for generations to come.

In Closing

Humans have an innate ability to speculate about and visualize the future. It’s in our DNA, a culmination of our ancestors’ desire to understand the world and survive within it. As you begin to explore the principles and methods in this book, you’ll see that these are just additional tools and devices that can be used to navigate time and space. Regardless of how you are applying these methods (for projects, strategic roadmaps, innovation, or planning your career), the mechanics of these methods shouldn’t differ from any subconscious process you use in your head today when you are strategizing how to plan a vacation, map out your career, buy a car, or start a family. Sensing and gathering these signals and vibrations in the world will allow you to easily construct your own map of the future and analyze how it works so that you can sail into and through the future more safely and productively. Once you’re able to tap into this ability and internalize the process, it won’t feel complex or intimidating. In the end, futuring should be exciting. No matter what threats or barriers you discover, you will hopefully be able to invite these uncertainties into your world as exhilarating problems to be solved.

1 Also known as the Johari window, a tool developed in 1955 by the American psychologists Joseph Luft and Harrington Ingham to help people improve their self-awareness and interpersonal relationships. It is used frequently in both counseling and corporate team development settings.

2 Reprinted in Paula M. Block, Star Trek: The Original Series 365, with Terry J. Erdmann (New York: Abrams, 2010).

3 Digital afterlife is associated with the volume of the digital assets and footprint left behind by people in the digital world—what happens with all your data once you die and how does it represent you, who owns it, and what happens to it when there is no physical body to own and manage it.

4 Wikipedia, s.v., “List of Black Mirror Episodes”, last modified March 24, 2024, and Wikipedia, s.v., “San Junipero”, last modified February 17, 2024.

5 Quantum computing is a rapidly emerging technology that harnesses the laws of quantum mechanics to solve problems too complex for classical computers. Unlike classical computers that process information on a series of bits and bytes of binary data (1s or 0s), quantum computers use Qbits, a type of information that can be a 1 and an 0 at the same time, removing the time and energy it takes to read and write a linear string of code of binary data. Quantum computers have already made enormous advancements, such as in the ability to solve mathematical problems in mere seconds that typically were unsolvable by classical computers.

Get Making Futures Work now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.