Chapter 4. Dock, Desktop & Toolbars

When you fire up a Mac, the first thing you see is the desktop—the great-great-grandchild of the original Mac’s home-base screen that changed the world in 1984. There’s the Dock, full of colorful icons on a see-through shelf. There are those Finder windows, slick and textureless with their solid-gray title bars. And then there’s the shimmering backdrop of the desktop itself.

This chapter shows you how to use and control these most dramatic elements of macOS Mojave’s home base.

The Dock

For years, most operating systems maintained two lists of programs. One listed unopened programs until you needed them, like the Start menu (Windows) or the Launcher (Mac OS 9). The other kept track of which programs were open at the moment for easy switching, like the taskbar (Windows) or the Application menu (Mac OS 9).

In macOS, Apple combined both functions into a single strip of icons called the Dock.

Apple’s thinking goes like this: Why must you know whether or not a program is already running? That’s the computer’s problem, not yours. In an ideal world, this distinction should be irrelevant. A program should appear when you click its icon, whether it’s open or not—just as on an iPhone or an iPad.

“Which programs are open” approaches unimportance in macOS, where sophisticated memory-management features make it hard to run out of memory. You can have dozens of programs open at once.

And that’s why the Dock combines the launcher and status functions of a modern operating system. Only a tiny black dot beneath a program’s icon tells you that it’s open—and you can even hide that, if you want. (Choose System Preferences → Dock, and turn off “Show indicators for open applications.”)

Apple has made it as easy as possible to like the Dock. You can customize the thing to within an inch of its life, use it to control and manipulate windows in elaborate ways, or even get rid of it completely. This section explains everything you need to know.

Setting Up the Dock

Apple starts the Dock off with a few icons it doesn’t want you to miss: Finder, Siri, News, App Store, Mail, the Safari web browser, and so on. But using your Mac without putting your own favorite icons in the Dock is like buying an expensive suit and then turning down the free alteration service. At the first opportunity, you should make the Dock your own.

The concept of the Dock is simple: Any icon you drag onto it (Figure 4-1) is installed there as a button. You can even drag an open window onto the Dock—a Microsoft Word document you’re editing, say—using its proxy icon (“The Folder Proxy Icon”) as a handle.

Tip

If you right-click or two-finger click a folder, or any other icon, in the Sidebar (“Windows and How to Work Them”), you get an Add to Dock command for that icon. Bet you can’t guess what it does.

Figure 4-1. To add an icon to the Dock, drag it there. You haven’t moved the original file. You’ve just installed a pointer—like a Mac alias or a Windows shortcut.

A single click, not a double-click, opens the corresponding icon. In other words, the Dock is an ideal parking lot for the icons of disks, folders, documents, programs, and internet bookmarks that you access frequently.

You can even install batches of icons onto the Dock all at once—just drag them as a group. That’s something you can’t do with the other parking places for favorite icons, like the Sidebar and the Finder toolbar.

Here are a few aspects of the Dock that may throw you at first:

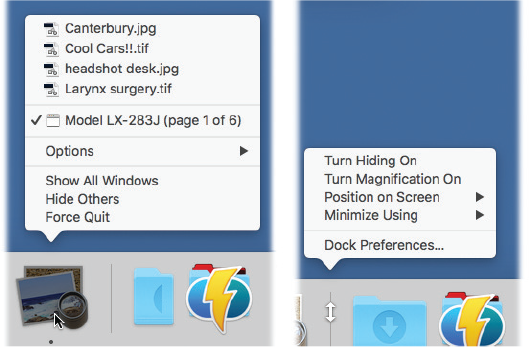

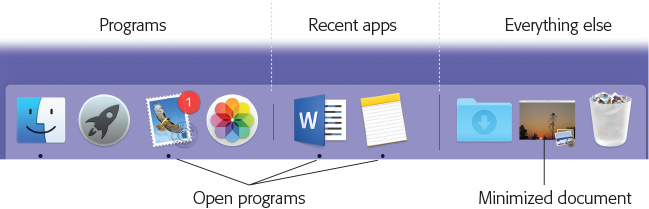

It has three sections. See the divider lines (Figure 4-1)? Everything on the left side is an application—a program. Then, in the middle, you get the icons for the apps you’ve most recently used. (If one of those apps is already represented on the Dock, it doesn’t appear here.)

Note

In System Preferences → Dock, you can turn off “Show recent applications in Dock” (the middle section), making more room for other Dock icons.

Everything else goes on the right side: files, documents, folders, disks, and minimized windows.

Remember this division. If you try to drag an application to the middle or right sections, for example, the Mac teasingly refuses to accept it.

Its icon names are hidden. To see the name of a Dock icon, point to it without clicking. The name appears above the icon.

Folders and disks sprout stacks. If you click a folder or a disk icon on the right side of the Dock, a list of its contents sprouts from the icon. It’s like X-ray vision without the awkward moral implications. Read on for details on stacks.

Tip

If you press Shift as you click, the stack opens in slow motion. Amaze your friends.

Programs appear there unsolicited. You can put stuff on the right side of the Dock, but not the left or middle. Program icons appear on the left side automatically whenever you open one, and stay there for as long as they’re running.

Organizing and Removing Dock Icons

You can move the tiles of the Dock around by dragging them horizontally. As you drag, the other icons scoot aside to make room. When you’re satisfied with its new position, drop the icon you’ve just dragged.

To remove a Dock icon, just drag it away. (You can’t remove the icons of the Finder, the Trash, or any minimized document window.) Once your cursor has cleared the Dock, release the mouse button. The icon disappears. The other Dock icons slide together to close the gap.

Something weird happens if you drag away a Dock program’s icon while that program is running. You don’t see any change immediately, because the program is still open. But when you quit the program, its previously installed icon disappears from the Dock.

Pop-Up Dock Folders (“Stacks”)

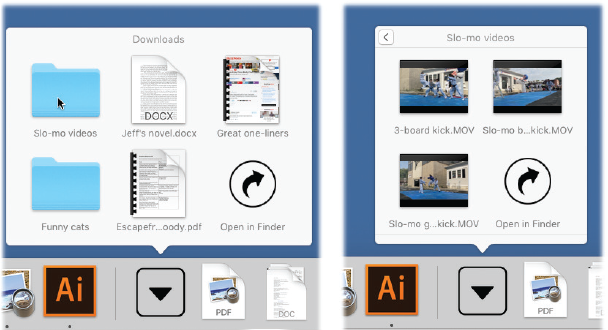

When you click a disk or folder icon on the Dock, you witness the effect shown in Figure 4-2. In essence, macOS is fanning out the folder’s contents so you can see all of them. If it could talk, it would be saying, “Pick a card, any card.”

Tip

You can change how the icons in a particular stack are sorted: alphabetically, chronologically, or whatever. Use the “Sort by” section of the shortcut menu.

In principle, of course, pop-up folders are a great idea, because they save you time and clicking. Click a folder to see what’s in it; click the icon you want inside; and you’re off and running, without having had to open, manage, and close a window. (It’s such a great idea, in fact, that it’s now available on the desktop, too; see “Desktop Stacks”.)

Anyway, here’s how to operate pop-up Dock folders.

Figure 4-2. What happens when you click a folder in the Dock? You see its contents in one of three views. Here’s how you choose the file you’re looking for in each:

Top left: In list view, the folder contents appear as a pop-up menu; you can “drill down” into subfolders, and you can open something by choosing its name.

Top right: In fan view, click an icon to open it.

Bottom: In grid view, many more icons appear than can fit in fan view.

In any of the views, you can get a quick look at a document’s contents by using Quick Look. That is, highlight the icon (point without clicking, or use the keyboard to select it), and then press the space bar. A window sprouts, showing the actual document contents.

Fan vs. grid vs. list

When you click a disk or folder icon on the Dock, what happens? You see its contents, arrayed in your choice of four displays:

Fan. The fan is a single, gently curved column of icons. It’s ideal for folders that contain very few icons, because there’s room for only a handful of items in a fan (the exact number depends on your screen size). After the first few, you see only a “31 More in Finder” button, which you can click to see everything in that folder—but now you’ve wasted time, not saved it.

Note

When your Dock is positioned on a side of the screen instead of the bottom, the fan option isn’t available.

Grid. If you’ve set a folder to open as a grid, you get to see all the icons in a big rectangular window. File names often get abbreviated because there’s not enough horizontal room, but you get to see many more icons this way. Actually, thanks to the scroll bar, you get to see all the icons this way.

Tip

A cool highlighting effect is available that makes it easier to see which icon you’re pointing to as you move your mouse around in a grid or a fan. To make it appear, click-and-hold a folder on the Dock—and then, without releasing the mouse, slide onto the grid or fan. The highlighting follows your cursor.

Alternatively, as soon as the grid or fan appears, press the arrow keys on your keyboard to move from icon to icon—complete with ghostly selection square.

List. You can also opt for a simple list of the folder’s contents, like a pop-up menu; you actually see little icons for the files and folders within. The list appears much faster than a fan or a grid does.

There’s no scroll bar, but you can scroll the list nonetheless just by pointing to the top or bottom of it with your mouse.

Tip

The list view also displays a little

to the right of each folder within the Dock folder. That is, it’s a hierarchical list, meaning you can burrow into folders within folders, all from the original Dock icon, and all without opening a single new window. You can stick your entire Home folder, or even your whole hard drive icon, onto the Dock; now you have complete menu access to everything inside, right from the Dock.

to the right of each folder within the Dock folder. That is, it’s a hierarchical list, meaning you can burrow into folders within folders, all from the original Dock icon, and all without opening a single new window. You can stick your entire Home folder, or even your whole hard drive icon, onto the Dock; now you have complete menu access to everything inside, right from the Dock.Automatic. There’s a fourth option in the shortcut menu for a Dock folder, too: Automatic. If you turn this on, then macOS chooses either fan or grid view, depending on how many icons are in the folder.

So how do you choose which display you want? Right-click or two-finger click the Dock folder’s icon, and make a selection from the shortcut menu. Each disk or folder icon remembers its own fan/grid/list setting.

The Finer Points of Pop-Up Dock Folders

Those were the basics of pop-up Dock folders. Here’s the advanced course:

Ever-Changing Folder-Icon Syndrome (ECFIS). When you add a folder or disk icon to the Dock, you might notice something disorienting: Its icon keeps changing to resemble whatever you most recently put into it. Your Downloads folder might look like an Excel spreadsheet icon today, a PDF icon tonight, and a photo icon tomorrow—but never a folder. You can’t get to know a folder by its icon.

Fortunately, this problem is easy to fix. Right-click or two-finger click the Dock folder. From the shortcut menu, in the “Display as” section, choose either Folder (which looks like a folder forever) or Stack (which changes to reflect its contents).

Ready-made pop-up folders. When you install macOS, you get a couple of starter Dock folders, just to get you psyched. One is Downloads; the other is Documents. (Both of these folders are physically inside your Home folder. But you may well do most of your interacting with them on the Dock.)

The Downloads folder collects all kinds of online arrivals: files you download from the web using Safari, files you receive in a Messages file-transfer session, file attachments you get via Mail, files sent to you using AirDrop (Chapter 13), and so on. Unless you intervene, they’re sorted by the date you downloaded them.

It’s handy to know where to find your downloads—and nice not to have them all cluttering your desktop.

Tip

Once you’ve opened a stack’s fan or grid, you can drag any of the icons right out of the fan or grid. Just drag your chosen icon onto the desktop or into any visible disk or folder. In other words, what lands in the Downloads folder doesn’t have to stay there. (You can’t drag out of a list, however.)

Hierarchical folders. The lists and grids are hierarchical—that is, you can drill down from their folders into their folders. Figure 4-3 makes this concept clearer.

Tip

Figure 4-3 shows you how to open a folder in a grid using the mouse—but you can do it all from the keyboard, too. Once a folder is selected, press Return,

-O, or

-O, or  -

- to see what’s inside it; press

to see what’s inside it; press  -

- to backtrack to the original display. When a folder is highlighted, you can press

to backtrack to the original display. When a folder is highlighted, you can press  -Return to open it in a Finder window; add the Option key to open that Finder window without closing the grid or list.

-Return to open it in a Finder window; add the Option key to open that Finder window without closing the grid or list.

Figure 4-3. If you spot a folder inside a grid (left), click it once. You’re now looking at a grid of its contents (right). You can go on burrowing like this as deeply as your folders go. You can also “back out” again by clicking the Back button (

) in the upper-left corner.

) in the upper-left corner.Type-selecting. Once a list, fan, or grid is on the screen, you can highlight any icon in it by typing the first few letters of its name. For example, once you’ve popped open your Applications folder, you can highlight Safari by typing sa. (Press Return to open the highlighted icon.)

Tip

Alternatively, you can “walk” through the fan, grid, or list by pressing the arrow keys. A highlighting effect makes it crystal clear which icon you’re selecting. Once an icon is selected, press Return to open it.

Two ways to bypass the pop-up. If you just want to see what’s in a folder, without all the graphic overkill of the fan or the grid, then right-click or two-finger click the Dock folder’s icon and choose the first command—Open “Applications” (or whatever the folder’s name is)—from the shortcut menu. You go straight to the corresponding window.

Actually, if you really value your time, you’ll learn the shortcut: Option-

-click the Dock folder’s icon. That accomplishes the same thing.

-click the Dock folder’s icon. That accomplishes the same thing.

Tip

Alternatively, you can ![]() -click a folder on the Dock—or, indeed, any icon on the Dock—to jump to the window that contains that folder’s icon. (Bonus: This same

-click a folder on the Dock—or, indeed, any icon on the Dock—to jump to the window that contains that folder’s icon. (Bonus: This same ![]() -clicking trick also works in the list of Spotlight search results.)

-clicking trick also works in the list of Spotlight search results.)

Three Ways to Get the Dock Out of Your Hair

The bottom of the screen isn’t necessarily the ideal location for the Dock. All Mac screens are wider than they are tall, so the Dock eats into your limited vertical screen space. You have three ways out: Hide the Dock, shrink it, or rotate it 90 degrees.

Auto-hiding the Dock

To turn on the Dock’s auto-hiding feature, press Option-![]() -D. (Or, if it’s a slow day at work, choose System Preferences → Dock →“Automatically hide and show the Dock.”)

-D. (Or, if it’s a slow day at work, choose System Preferences → Dock →“Automatically hide and show the Dock.”)

When the Dock is hidden, it appears only when you move your cursor to the Dock’s edge of the screen. (Individual Dock icons may still occasionally shoot upward into desktop territory when an app needs attention—cute, very cute.)

In practice, you may prefer to hide and show the Dock at will by pressing the hide/show keystroke, Option-![]() -D. This method makes the Dock pop on and off the screen without requiring you to move the cursor.

-D. This method makes the Dock pop on and off the screen without requiring you to move the cursor.

Shrinking and enlarging the Dock

Depending on your screen’s size, you may prefer smaller or larger Dock buttons. The official way to resize them is shown in Figure 4-4.

Figure 4-4. To make your Dock icons bigger or smaller, choose System Preferences → Dock, and experiment with the Size slider.

There’s a much faster way to resize the Dock, though: Just position your cursor carefully on the Dock’s divider line so that it turns into a double-headed arrow (shown in Figure 4-5). Now drag up or down to enlarge or shrink the Dock.

Tip

If you press Option as you drag, the Dock snaps to certain canned icon sizes—those that the programmer actually drew. (You won’t see the in-between sizes that macOS generally calculates on the fly.)

Figure 4-5. Look closely—you can see the secret cursor that resizes the Dock. If you don’t see any change in the Dock size as you drag upward, then you’ve reached the size limit.

You may not be able to enlarge the Dock if it’s already at its size limit. But you can make it almost infinitely smaller. This may make you wonder: How can you distinguish among icons if they’re the size of molecules?

The answer lies in the Magnification option (see Figure 4-4). Now your Dock icons balloon to a much larger size as your cursor passes over them.

Tip

You can get Dock magnification à la carte, too. If you press Shift-Control as your cursor approaches the Dock, you temporarily reverse the magnification setting. That is, if magnification is turned off, the icons now swell into magnification mode—and vice versa.

Moving the Dock to the sides of the screen

Yet another approach to getting the Dock out of your way is to rotate it, so that it sits vertically against a side of your screen. You can rotate it in either of two ways:

The long way. Choose System Preferences → Dock, and choose Left, Bottom, or Right, as you see fit.

The mouse way. While pressing Shift, drag the Dock’s divider line, like a handle, to the side of the screen you want.

You’ll probably find that the right side of your screen works better than the left. Most macOS programs put their document windows against the left edge of the screen, where the Dock and its labels might get in the way.

Note

When you position your Dock vertically, the “right” side of the Dock becomes the bottom of the Dock. In other words, the Trash now appears at the bottom of the vertical Dock. So, in this book, mentally substitute the phrase “bottom part of the Dock” when you read references to the “right side of the Dock.”

Using the Dock

Most of the time, you’ll use the Dock as either a launcher (you click an icon once to open the corresponding program, file, folder, or disk) or as a status indicator (the tiny spots identified in Figure 4-1 indicate which programs are running).

But the Dock has more tricks than that up its sleeve. You can use it, for example, to pull off any of the following stunts.

Switch Applications

The Dock isn’t just a launcher; it’s also a switcher. Here are some of the tricks it lets you do:

Jump among your open programs by clicking their icons.

Drag a document (such as a text file) onto a Dock application (such as the Microsoft Word icon) to open the former with the latter. (If the program balks at opening the document, yet you’re sure the program should be able to open it, then add the

and Option keys as you drag.)

and Option keys as you drag.)Hide all windows of the program you’re in by Option-clicking another Dock icon.

Hide all other programs’ windows by Option-

-clicking the Dock icon of the program you do want (even if it’s already in front).

-clicking the Dock icon of the program you do want (even if it’s already in front).Switch windows in one program by pointing to that program’s Dock icon without clicking and then doing a three-finger downward swipe on your trackpad. (This feature, called App Exposé, doesn’t work until you turn it on in System Preferences → Trackpad → More Gestures.)

Tip

This trick—the three-finger downswipe—works even on the Dock icons of Apple programs that aren’t running. In those situations, you get the effect shown in Figure 5-17. For some Apple programs, at least, it’s a quick way to get to the icons of recently opened documents.

Operate the Dock by Keyboard Control

If you turn on keyboard navigation, you can operate the Dock entirely from the keyboard; see “Reassigning all documents of one type”.

Conduct Speed Tests

When you click an application icon in the Dock, its icon jumps up and down a few times as the program launches, as though with excitement at having been selected. The longer a program takes to start up, the more bounces you see. This has given birth to a hilarious phenomenon: counting these bounces as a casual speed benchmark for application-launching times. “InDesign took twelve bouncemarks to open in Mac OS X 10.10,” you might read online, “but only three bouncemarks in 10.12.”

Tip

If you find the icon-bouncing a bit over the top, try this: Choose System Preferences → Dock. Turn off “Animate opening applications.” From now on, your icons won’t actually bounce—instead, the little dot underneath it will simply pulse as the application opens.

Drag and Drop

Dock icons are spring-loaded. That is, if you drag any icon onto a Dock folder or disk icon and pause—or, if you’re in a hurry, tap the space bar—the Dock icon opens to receive the dragged file.

Note

It opens, that is, if the spring-loading delay feature is turned on in System Preferences → Accessibility → Mouse & Trackpad.

This technique is most useful in these situations:

Drag a document icon onto a Dock folder icon. The folder’s Finder window pops open so you can continue the drag into a subfolder.

Drag a document into an application. The classic example is dragging a photo onto the Photos icon. When you tap the space bar, Photos opens automatically. Since your mouse button is still down, and you’re technically still in mid-drag, you can now drop the photo directly into the appropriate Photos album or Event.

You can drag an MP3 file into iTunes or an attachment into Mail or Outlook in the same way.

Do Your Filing

Once you’ve tried stashing a few important folders on the right side of your Dock, you’ll never look back. You can mostly forget all the other navigation tricks you’ve learned in macOS. The folders you care about are always there, ready for opening with a single click.

Better yet, they’re easily accessible for putting away files; you can drag files directly into the Dock’s folder icons as though they were regular folders.

In fact, you can even drag a file into a subfolder in a Dock folder. That’s because, again, Dock folders are spring-loaded. When you drag an icon onto a Dock folder and pause, the folder’s window appears around your cursor, so you can continue the drag into an inner folder (and even an inner inner folder, and so on). “Spring-Loaded Folders: Dragging Icons into Closed Folders” has the details on spring-loaded folders.

Tip

When you try to drag something into a folder on the Dock, the Dock icons scoot out of the way; the Dock assumes you’re trying to put that something onto the Dock. But if you press the ![]() key as you drag an icon to the Dock, the existing icons freeze in place. Without the

key as you drag an icon to the Dock, the existing icons freeze in place. Without the ![]() key, you wind up playing a frustrating game of chase-the-folder.

key, you wind up playing a frustrating game of chase-the-folder.

Find Great Things to Put in Your Dock

Now that you know what the Dock is about, it’s time to set up shop, installing the programs, folders, and disks you’ll be using most often.

They can be whatever you want, of course, but don’t miss these opportunities:

Your Home folder. Many people immediately drag their hard drive icons—or, perhaps more practically, their Home folders—onto the right side of the Dock. Now they have quick access to every file in every folder they ever use.

The Applications folder. Here’s a no-brainer: Stash the Applications folder here so you’ll have quick pop-up-menu access to any program on your machine.

Your Applications folder. As an even more efficient corollary, create a new folder of your own. Fill it with the aliases of just the programs you use most often and park it in the Dock. Now you’ve got an even more useful Applications folder that opens as a stack.

The Shared folder. If you’re using the Mac’s accounts feature (Chapter 12), this is your wormhole to all the accounts—the one place you can put files where everybody can access them (“Fast User Switching”).

A tag. You know those color-coded Finder tags (“Finder Tags”)? You can drag one directly out of a Finder window’s Sidebar and onto the right side of the Dock. When you click its Dock icon, you get a window that displays the icons of everything on your Mac you’ve tagged that way.

The Finder Toolbar

At the top of every Finder window is a small set of function icons, all in a gradient-gray row (Figure 4-7). The first time you run macOS, you’ll find only these icons on the toolbar:

Back (

), Forward (

), Forward ( ). The Finder works something like a web browser. Only a single window remains open as you navigate the various folders on your hard drive.

). The Finder works something like a web browser. Only a single window remains open as you navigate the various folders on your hard drive.The Back button (

) returns you to whichever folder you were just looking at. (Instead of clicking

) returns you to whichever folder you were just looking at. (Instead of clicking  , you can also press

, you can also press  -[, or choose Go → Back—particularly handy if the toolbar is hidden, as described in the next section.)

-[, or choose Go → Back—particularly handy if the toolbar is hidden, as described in the next section.)The Forward button (

) springs to life only after you’ve used the Back button. Clicking it (or pressing

) springs to life only after you’ve used the Back button. Clicking it (or pressing  -]) returns you to the window you just backed out of.

-]) returns you to the window you just backed out of.

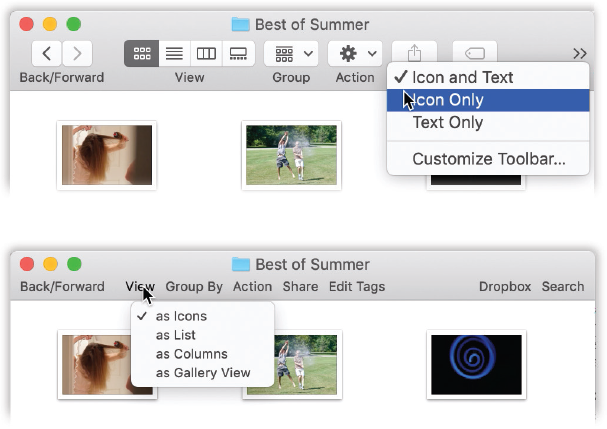

Figure 4-7. If you right-click or two-finger click a blank spot on the toolbar, you get a pop-up menu that offers you a choice of three looks for the buttons here: Icon and Text, Icon Only, or Text Only. (Well, four looks, if you count Customize Toolbar.)

In Text Only mode (bottom), the four View buttons are replaced by a little pop-up menu called View. Furthermore, the search box turns into a one-word button called Search. Clicking it brings up the search window.View controls. The four tiny View buttons switch the current window into icon, list, column, or gallery view, respectively. And, remember, if the toolbar is hidden, you can get by with the equivalent commands in the View menu at the top of the screen—or by pressing

-1 for icon view,

-1 for icon view,  -2 for list view,

-2 for list view,  -3 for column view, or

-3 for column view, or  -4 for gallery view.

-4 for gallery view.Group (

). This pop-up menu lets you group the files in a window by date, name, or other criteria; see “Group By and Sort By”.

). This pop-up menu lets you group the files in a window by date, name, or other criteria; see “Group By and Sort By”.Action (

). You can read about this context-sensitive pop-up menu in “New Folder with Selection”.

). You can read about this context-sensitive pop-up menu in “New Folder with Selection”.Share (

). You can read about this context-sensitive pop-up menu in “Does the file have the correct file name suffix?”.

). You can read about this context-sensitive pop-up menu in “Does the file have the correct file name suffix?”.Tags (

). Here’s the Tags menu described in “Finder Tags”.

). Here’s the Tags menu described in “Finder Tags”.Search box. This little round-ended text box is yet another entry point for the Spotlight feature described in Chapter 3. It’s a handy way to search your Mac for some file, folder, disk, or program.

Hiding or Shrinking the Toolbar

With the toolbar, the Dock, the Sidebar, and the large icons of macOS, it almost seems like there’s an Apple conspiracy to sell big screens.

Fortunately, the toolbar doesn’t have to contribute to that impression. You can hide it by choosing View → Hide Toolbar or by pressing Option-![]() -T. (That will work only if you don’t have multiple tabs in that Finder window.) That same keystroke, or choosing View → Show Toolbar, brings it back. You can also just make it smaller by hiding the labels (or the icons), as shown in Figure 4-7.

-T. (That will work only if you don’t have multiple tabs in that Finder window.) That same keystroke, or choosing View → Show Toolbar, brings it back. You can also just make it smaller by hiding the labels (or the icons), as shown in Figure 4-7.

Customizing the Icons on the Toolbar

MacOS offers a collection of beautifully designed icons for alternate (or additional) toolbar buttons. But you can also add anything to the toolbar, turning it into a supplementary Dock or Sidebar. This is great news for people who’ve run out of space for stashing favorite icons in the Dock or the Sidebar. (Of course, if that’s your problem, you need a bigger monitor.)

Apple’s toolbar-icon collection

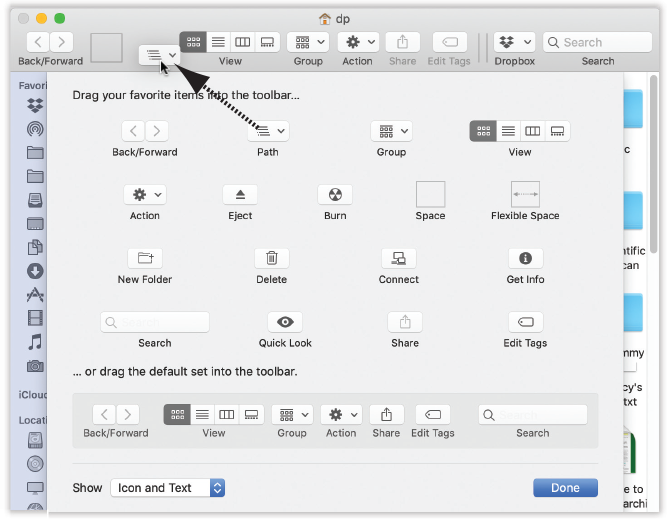

The first step in tweaking the toolbar is choosing View → Customize Toolbar. The window shown in Figure 4-8 appears.

Figure 4-8. While this window is open, you can add icons to the toolbar by dragging them into place from the gallery before you. You can also remove icons from the toolbar by dragging them up or down off the toolbar. Rearrange the icons by dragging them horizontally.

![]() This is your chance to rearrange the existing toolbar icons or delete the ones you don’t use. You can also add any of Apple’s buttons to the toolbar by dragging them from the “gallery” onto the toolbar itself. The existing icons scoot out of your cursor’s way, if necessary.

This is your chance to rearrange the existing toolbar icons or delete the ones you don’t use. You can also add any of Apple’s buttons to the toolbar by dragging them from the “gallery” onto the toolbar itself. The existing icons scoot out of your cursor’s way, if necessary.

Most of the options in the gallery duplicate the functions of menu commands. Here are a few that don’t appear on the standard toolbar:

Path. Most of the gallery elements are buttons, but this one creates a pop-up menu on the toolbar. When clicked, it reveals (and lets you navigate) the hierarchy—the path—of folders you open to reach whichever window is open. (Equivalent:

-clicking a window’s title.)

-clicking a window’s title.)Eject. This button ejects whichever disk or disk image is currently highlighted. (Equivalent: the File → Eject command, or holding down the

key, if you have it on your keyboard.)

key, if you have it on your keyboard.)Burn. This button burns a blank CD or DVD with the folders and files you’ve dragged onto it. (Equivalent: the File → Burn [Thing Name] to Disc command.)

Space. By dragging this mysterious-looking item into the toolbar, you add a gap between it and whatever icon is to its left. The gap is about as wide as one icon. (The fine, dark, rectangular outline that appears when you drag it doesn’t actually show up once you click Done.)

Flexible Space. This icon, too, creates a gap between the toolbar buttons. But this one expands as you make the window wider. Now you know how Apple got the search box to appear off to the right of the standard toolbar, a long way from its clustered comrades to the left.

New Folder. Clicking this button creates a new folder in whichever window you’re viewing. (Equivalent: the File → New Folder command, or the Shift-

-N keystroke.)

-N keystroke.)Delete. This option puts the highlighted file or folder icons into the Trash. (Equivalent: the File → Move to Trash command, or the

-Delete keystroke.)

-Delete keystroke.)Tip

Weirdly enough, if you highlight an icon in the Trash and then press

-Delete, you trigger the Put Back function—flinging the icon back into the folder it came from (and opening that folder to show you). That is, using the

-Delete, you trigger the Put Back function—flinging the icon back into the folder it came from (and opening that folder to show you). That is, using the  -Delete keystroke in this case actually undeletes.

-Delete keystroke in this case actually undeletes.Connect. If you’re on a home or office network, this opens the Connect to Server dialog box so you can tap into another computer. (Equivalent: the Go → Connect to Server command, or

-K.)

-K.)Get Info. This button opens the Get Info window for whatever’s selected.

Drag the default set. If you’ve made a mess of your toolbar, you can always reinstate its original Apple arrangement by dragging this rectangular strip directly upward onto your toolbar.

Quick Look. Triggers a preview of the icon (“Quick Look”).

If the window ever gets too narrow to show all the icons you’ve added to the toolbar, the right end of the toolbar sprouts a » symbol. Click it for a pop-up menu that names whichever icons don’t fit at the moment. (You’ll find this toolbar behavior in many macOS programs, not just the Finder: Safari, Mail, and so on.)

Adding your own stuff

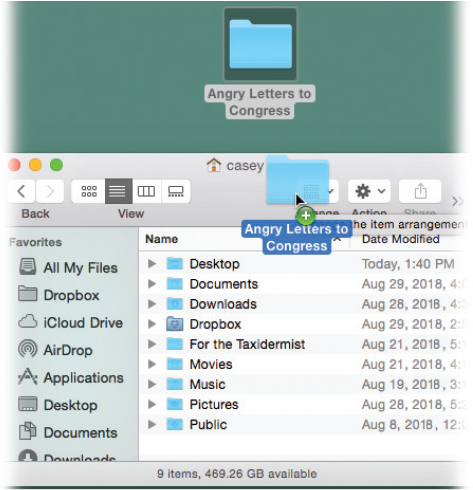

Millions of Mac fans never realize that they can drag any icons at all onto the toolbar—files, folders, disks, programs, or whatever—to turn them into one-click buttons.

In short, you can think of the Finder toolbar as yet another Dock or Sidebar (Figure 4-9).

Figure 4-9. You don’t need to choose View → Customize Toolbar to add your own icons to the toolbar. Just hold down the  and Option keys, and then drag an icon from the desktop or any folder window directly onto the toolbar at any time.

and Option keys, and then drag an icon from the desktop or any folder window directly onto the toolbar at any time.

To remove the icon later, press  as you drag it away from the toolbar.

as you drag it away from the toolbar.

Rearranging or Removing Toolbar Icons

You can drag toolbar icons around, rearranging them horizontally, by pressing ![]() as you drag. Taking an icon off the toolbar is equally easy. While pressing the

as you drag. Taking an icon off the toolbar is equally easy. While pressing the ![]() key, just drag the icon clear away from the toolbar. (If the Customize Toolbar sheet is open, you can perform either step without the

key, just drag the icon clear away from the toolbar. (If the Customize Toolbar sheet is open, you can perform either step without the ![]() key. You can also get rid of a toolbar icon by right-clicking or two-finger clicking it and choosing Remove Item from the shortcut menu.)

key. You can also get rid of a toolbar icon by right-clicking or two-finger clicking it and choosing Remove Item from the shortcut menu.)

Designing Your Desktop

In some ways, just buying a Macintosh was already a renegade act of self-expression. But that’s only the beginning. Now it’s time to fashion the computer screen itself according to your personal sense of design and fashion.

Backgrounds and Screen Savers

Cosmetically speaking, macOS offers two dramatic full-screen features: desktop backgrounds and screen savers. For details, see “Desktop & Screen Saver”.

Accent Colors

For years, macOS has offered a choice of accent colors—used for scroll-bar handles, progress bars, OK buttons, highlighted menu names and commands, and so on.

Well, it wasn’t a huge choice. You could choose either the standard blue or Graphite (gray). Graphite was intended to pacify Apple’s core constituency: artists and graphic designers, some of whom complained that the lively, brightly colored look of the Mac threw off their color judgment.

In macOS Mojave, Graphite is only one of eight available accent colors. Choose System Preferences → General, and then choose from the “Accent color” dots.

While you’re here, say hello to the “Highlight color” pop-up menu. This is an accent color, too—the background color of highlighted text, the colored oval that appears around highlighted icon names, and a window’s “lining” as you drag an icon into it.

Dark Mode

The System Preferences panel just described (General) offers another option, too—one of the most arresting and radical design changes in Mac history. It’s Dark Mode (Figure 4-10). You’re also offered the chance to turn it on during the installation process.

Dark Mode is a dark-gray color scheme. Once you turn it on, most of Apple’s built-in apps—Finder, Mail, Calendar, Photos, Messages, iTunes, Notes, Xcode, and so on—take on a stunning, white-on-black appearance.

Here’s what doesn’t change in Dark Mode:

Your desktop picture. Or any pictures at all, for that matter.

Web pages in Safari.

Preexisting non-Apple apps. Software companies have to update their programs if they want them to take on Dark Mode’s dusky hues.

In general, you’d really have to stretch to say Dark Mode helps with your productivity. Mainly it’s just cool-looking.

Note

If you’re using one of the two dynamic wallpaper options (“Desktop & Screen Saver”), then turning on Dark Mode also jumps to the nighttime versions of those images.

Figure 4-10. Some people argue that Dark Mode blasts less obnoxious light from the screen to your sleeping partner when you’re working in bed. Others say Dark Mode makes photos stand out more, or that it’s less fatiguing to your eyes.

Desktop Sounds

Desktop sounds are the tiny sound effects that accompany certain mouse drags. And we’re talking tiny—they’re so subdued that you might not have noticed them. You hear a little plink/crunch when you drop an icon onto the Trash, a boingy thud when you drag something into a folder, and so on. The little thud you hear at the end of a file-copying job is actually useful, because it alerts you that the task is complete.

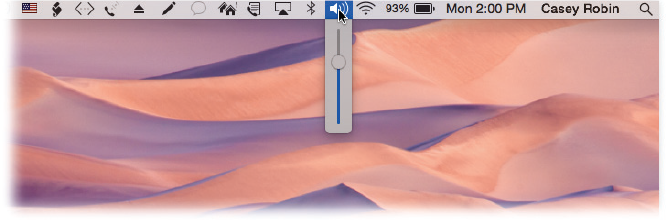

If all that racket is keeping you awake, however, it’s easy enough to turn it off. Open System Preferences, click the Sound icon, and then turn off “Play user interface sound effects.”

And if you decide to leave them turned on, please—use discretion when working in a library, church, or neurosurgical operating room.

Get macOS Mojave: The Missing Manual now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.