Preface

Once upon a time, Unix came with only a few standard utilities and, if you were lucky, included a C compiler. When setting up a new Unix system, you’d have to crawl the Net looking for important software: Perl, gcc, bison, flex, less, Emacs, and other utilities and languages. That was a lot of software to download through a 28.8-Kbps modem. These days, Unix distributions come with much more, and it seems like more and more users are gaining access to a wide-open pipe.

Free Linux distributions pack most of the GNU tools onto a CD-ROM, and now commercial Unix systems are catching up. IRIX includes a big selection of GNU utilities, Solaris comes with a companion CD of free software, and just about every flavor of Unix (including Mac OS X) now includes Perl. Mac OS X comes with many tools, most of which are open source and complement the tools associated with Unix.

This book serves as a bridge for Unix developers and system administrators who’ve been lured to Mac OS X because of its Unix roots. When you first launch the Terminal application, you’ll find yourself at home in a Unix shell, but like Apple’s credo, “Think Different,” you’ll soon find yourself doing things a little differently. Some of the standard Unix utilities you’ve grown accustomed to may not be there, /etc/passwd and /etc/group have been supplanted with something called NetInfo, and when it comes to developing applications, you’ll find that things like library linking and compiling have a few new twists to them.

Despite all the beauty of Mac OS X’s Aqua interface, you’ll find that some things are different on the Unix side. But rest assured, they’re easy to deal with if you know what to do. This book is your survival guide for taming the Unix side of Mac OS X.

Audience for This Book

This book is aimed at Unix developers, a category that includes programmers who switched to Linux from a non-Unix platform, web developers who spend most of their time in ~/public_html over an ssh connection, and experienced Unix hackers. In catering to such a broad audience, we chose to include some material that advanced users might consider basic. However, this choice makes the book accessible to all Unix programmers who switch to Mac OS X as their operating system of choice, whether they have been using Unix for one year or ten. If you are coming to Mac OS X with no Unix background, we suggest that you start with Learning Unix for Mac OS X Tiger by Dave Taylor (O’Reilly) to get up to speed with the basics.

Organization of This Book

This book is divided into five parts. Part I helps you map your current Unix knowledge to the world of Mac OS X. Part II discusses compiling and linking applications. Part III takes you into the world of Fink and covers packaging. Part IV discusses using Mac OS X as a server and provides some basic system management information. Part V provides useful reference information.

Here’s a brief overview of what’s in the book:

- Part I, Getting Around

This part of the book orients you to Mac OS X’s unique way of expressing its Unix personality.

- Chapter 1, Inside the Terminal

This chapter provides you with an overview of the Terminal application, including a discussion of the differences between the Terminal and the standard Unix xterm.

- Chapter 2, Searching and Metadata

Mac OS X Tiger introduces Spotlight, a new subsystem for searching your Mac. In this chapter, you’ll learn how to access this powerful metadata store from the command line.

- Chapter 3, The Mac OS X Filesystem

Here you’ll learn about the layout of the Mac OS X filesystem, as well as descriptions of key directories and files.

- Chapter 4, Startup

This chapter describes the Mac OS X boot process, from when the Apple icon first appears on your display to when the system is up and running.

- Chapter 5, Directory Services

Use this chapter to get started with Mac OS X’s powerful system for Directory Services, which replaces or complements the standard Unix flat files in the /etc directory.

- Chapter 6, Printing

This chapter explains how to set up a printer under Mac OS X and shows you around CUPS, the open source printing engine under Mac OS X’s hood.

- Chapter 7, The X Window System

In this chapter, you’ll learn how to install and work with the X Window System on Mac OS X.

- Chapter 8, Multimedia

This chapter discusses working with multimedia, including burning CDs, displaying video, and manipulating images.

- Chapter 9, Third-Party Tools and Applications

This chapter introduces some third-party applications that put a new spin on Unix features, such as virtual desktops, SSH frontends, and TeX applications.

- Chapter 10, Dual-Boot and Beyond

Mac OS X isn’t the only operating system you can run on your Mac. In this chapter, you’ll learn how you can run many operating systems on your Mac, perhaps even two or three at a time.

- Part II, Building Applications

Although Apple’s C compiler is based on the GNU Compiler Collection (GCC), there are important differences between compiling and linking on Mac OS X and on other platforms. This part of the book describes these differences.

- Chapter 11, Compiling Source Code

This chapter describes the peculiarities of the Apple C compiler, including using macros that are specific to Mac OS X, working with precompiled headers, and configuring a source tree for Mac OS X.

- Chapter 12, Libraries, Headers, and Frameworks

Here we’ll discuss building libraries, linking, and miscellaneous porting issues you may encounter with Mac OS X.

- Part III, Working with Packages

There are a good number of packaging options for software that you compile, as well as software you obtain from third parties. This part of the book covers software packaging on Mac OS X.

- Chapter 13, Fink

In this chapter, you’ll learn all about Fink, a package management system and porting effort that brings many open source applications to Mac OS X.

- Chapter 14, DarwinPorts

DarwinPorts offers another way to install lots of open source software on your Mac. You’ll learn all about it in this chapter.

- Chapter 15, Creating and Installing Packages

This chapter describes the native package formats used by Mac OS X, as well as packaging options you can use to distribute applications.

- Part IV, Serving and System Management

This part of the book talks about using Mac OS X as a server, as well as system administration.

- Chapter 16, Using Mac OS X as a Server

In this chapter, you’ll learn about setting up your Macintosh to act as a server, selectively letting traffic in (even through a Small Office/Home Office firewall such as the one found in the AirPort base station), and setting up Postfix.

- Chapter 17, System Management Tools

This chapter describes commands for monitoring system status and configuring the operating system.

- Chapter 18, Free Databases

This chapter explains how to set up and configure MySQL and PostgreSQL, and how to work with SQLite, the embeddable lightweight SQL system that comes with Mac OS X.

- Chapter 19, Perl and Python

This chapter describes the versions of Perl and Python that ship with Mac OS X, as well as optional modules that can make your experience that much richer.

- Part V, Appendixes

The final part of the book includes miscellaneous reference information.

- Appendix A, Mac OS X GUI Primer

If you are totally new to Mac OS X, this appendix will get you up to speed with the basics of its user interface and introduce terminology that we’ll use throughout the book.

- Appendix B, Mac OS X’s Unix Development Tools

This appendix provides a list of various development tools, along with brief descriptions.

Xcode Tools

This book assumes that you have installed the Xcode Tools, which includes the latest version of gcc, ported by Apple. If you bought the boxed version of Mac OS X, Xcode should be included on a separate CD-ROM. If you bought a boxed version of Mac OS X Tiger, you can find the installer for Xcode in the Xcode folder on the same DVD that you used to install Tiger. Failing either of those, or if you’d like to get the latest version of the tools, they are available to Apple Developer Connection (ADC) members at http://connect.apple.com.

Where to Go for More Information

Although this book will get you started with the Unix underpinnings of Mac OS X, there are many online resources that can help you get a better understanding of Unix for Mac OS X:

- Apple’s Open Source Mailing Lists

This site leads to all the Apple-hosted Darwin mailing lists, and includes links to list archives.

http://developer.apple.com/darwin/mail.html - The Darwin Project

Darwin is a complete Unix operating system for x86 and PowerPC processors. Mac OS X is based on the Darwin project. Spend some time at the project’s web page to peek as deep under Mac OS X’s hood as is possible.

http://developer.apple.com/darwin/ - Open Darwin

The Open Darwin project was founded in 2002 by Apple Computer and the Internet Software Consortium, Inc. (ISC). It is an independent project with a CVS repository that is separate from Apple’s Darwin project, but it aims for full binary compatibility with Mac OS X.

http://www.opendarwin.org/ - Fink

Fink is a collection of open source Unix software that has been ported to Mac OS X. It is based on the Debian package management system, and includes utilities to easily mix precompiled binaries and software built from source. Fink also includes complete GNOME and KDE desktop distributions.

http://fink.sourceforge.net/ - DarwinPorts

DarwinPorts is a project of OpenDarwin that provides a unified porting system for Darwin, Mac OS X, FreeBSD, and Linux. At the time of this writing, it includes thousands of ports, including the GNOME desktop system.

http://darwinports.opendarwin.org/ - GNU-Darwin

Like Fink, GNU-Darwin brings many free Unix applications to Darwin and Mac OS X. GNU-Darwin uses the FreeBSD ports system, which automates source code and patch distribution, as well as compilation, installation, and resolution of dependencies.

http://gnu-darwin.sourceforge.net/ - Mac OS X Hints

Mac OS X Hints presents a collection of reader-contributed tips, along with commentary from people who have tried the tips. It includes an extensive array of Unix tips.

http://www.macosxhints.com/ - Stepwise

Before Mac OS X, Stepwise was the definitive destination for OpenStep and WebObjects programmers. Now Stepwise provides news, articles, and tutorials for Cocoa and WebObjects programmers.

http://www.stepwise.com/ - VersionTracker

VersionTracker keeps track of software releases for Mac OS X and other operating systems.

http://www.versiontracker.com/ - MacUpdate

MacUpdate also tracks software releases for Mac OS X.

http://www.macupdate.com/ - FreshMeat’s Mac OS X Section

FreshMeat catalogs and tracks the project history of thousands of mostly open source applications.

http://osx.freshmeat.net/

Conventions Used in This Book

The following typographical conventions are used in this book:

- Italic

Used to indicate new terms, example URLs, filenames, file extensions, directories, commands and options, Unix utilities, and to highlight comments in examples. For example, a path in the filesystem will appear in the text as /Applications/Utilities.

-

Constant width Used to show functions, variables, keys, attributes, the contents of files, or the output from commands.

-

Constant width bold Used in examples and tables to show commands or other text that should be typed literally by the user.

-

Constant width italic Used in examples and tables to show text that should be replaced with user-supplied values.

- Menus/Navigation

Menus and their options are referred to in the text as File → Open, Edit → Copy, etc. Arrows are also used to signify a navigation path when using window options; for example: System Preferences → Accounts →

username→ Password means that you would launch System Preferences, click the icon for the Accounts preference panel, select the appropriateusername, and then click on the Password pane within that panel.- Pathnames

Pathnames are used to show the location of a file or application in the filesystem. Directories (or folders for Mac and Windows users) are separated by a forward slash. For example, if you’re told to “...launch the Terminal application (/Applications/Utilities),” it means you can find the Terminal application in the Utilities subfolder of the Application folder.

$,#The dollar sign (

$) is used in some examples to show the user prompt for the bash shell; the hash mark (#) is the prompt for the root user.- ↲

Used in place of a carriage return.

- Menu symbols

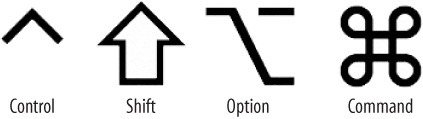

When looking at the menus for any application, you will see some symbols associated with keyboard shortcuts for a particular command. For example, to open a document in Microsoft Word, you could go to the File menu and select Open (File → Open), or you could issue the keyboard shortcut, ⌘-O.

Figure P-1 shows the symbols used in the various menus to denote a keyboard shortcut.

Figure P-1. These symbols, used in Mac OS X’s menus, are used for issuing keyboard shortcuts so you can quickly work with an application without having to use the mouse.Rarely will you see the Control symbol used as a menu command option; it’s more often used in association with mouse clicks to emulate a right click on a two-button mouse or for working with the bash shell.

Comments and Questions

Please address comments and questions concerning this book to the publisher:

| O’Reilly Media, Inc. |

| 1005 Gravenstein Highway North |

| Sebastopol, CA 95472 |

| (800) 998-9938 (in the United States or Canada) |

| (707) 829-0515 (international/local) |

| (707) 829-0104 (fax) |

To comment or ask technical questions about this book, send email to:

| bookquestions@oreilly.com |

We have a web site for the book, where we list examples, errata, and any plans for future editions. The site also includes a link to a forum where you can discuss the book with the author and other readers. You can access this site at:

| http://www.oreilly.com/catalog/macxtigerunix/ |

For more information about books, conferences, Resource Centers, and the O’Reilly Network, see the O’Reilly web site at:

| http://www.oreilly.com |

Safari Enabled

When you see a Safari® Enabled icon on the cover of your favorite technology book, it means the book is available online through the O’Reilly Network Safari Bookshelf.

Safari offers a solution that’s better than e-books. It’s a virtual library that lets you easily search thousands of top technology books, cut and paste code samples, download chapters, and find quick answers when you need the most accurate, current information. Try it for free at http://safari.oreilly.com.

Acknowledgments from the Previous Editions

This book builds on Mac OS X for Unix Geeks, for which we had help from a number of folks:

The folks at the ADC, for technical review and handholding in so many tough spots!

Erik Ray, for some early feedback and pointers to areas of library linking pain.

Simon St.Laurent for feedback on early drafts, and prodding us towards more Fink coverage.

Chris Stone, for tech review and helpful comments on the Terminal application.

Tim O’Reilly, for deep technical and editorial help.

Brett McLaughlin, for lots of great technical comments as well as helpful editorial ones.

Brian Aker, for detailed technical review and feedback on Unixy details.

Chuck Toporek, for editing, tech review, and cracking the whip when we needed it.

Elaine Ashton and Jarkko Hietaniemi, for deeply detailed technical review, and help steering the book in a great direction.

Steven Champeon, for detailed technical review and help on Open Firmware and the boot process.

Simon Cozens, for technical review and pushing us toward including an example of how to build a Fink package.

Wilfredo Sanchez, for an immense amount of detail on everything, and showing us the right way to do a startup script under Jaguar. His feedback touched nearly every aspect of the book, without which there would have been gaping holes and major errors.

Andy Lester, Chris Stone, and James Duncan Davidson for reviewing parts of the book and pointing out spots that needed touching up.

Acknowledgments from Brian Jepson

Thanks to Nathan Torkington, Rael Dornfest, and Chuck Toporek for helping shape and launch this book, and to Ernie Rothman for joining in to make it a reality. Thanks also to Jason Deraleau who started out assisting Chuck with some editing tasks, but then left to go write a book of his own. I’d especially like to thank my wife, Joan, and my stepsons, Seiji and Yeuhi, for their support and encouragement through my late night and weekend writing sessions, my zealous rants about the virtues of Mac OS X, and the slow but steady conversion of our household computers to Macintoshes.

Acknowledgments from Ernest E. Rothman

I would first like to thank Brian Jepson, who conceived the book and was generous enough to invite me to participate in its development. I would like to express my gratitude to both Brian and Chuck Toporek for their encouragement, patience, stimulating discussions, and kindness. I am also grateful to reviewers for useful suggestions and insights, to visionary folks at Apple Computer for producing and constantly improving Mac OS X, and to developers who spend a great deal of time writing applications and posting helpful insights on newsgroups, mailing lists, and web sites. Finally, I am very grateful to my lovely wife, Kim, for her love, patience, and encouragement, and to my Newfoundland dogs, Max and Joe, for their love, and patience.

Get Mac OS X Tiger for Unix Geeks, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.