LOGISTIC S & SUPPLY CHAIN MANAGEMENT

46

Setting customer service priorities

Whilst it should be the objective of any logistics system to provide all customers

with the level of service that has been agreed or negotiated, it must be recog-

nised that there will inevitably need to be service priorities. In this connection the

Pareto Law, or 80/20 rule, can provide us with the basis for developing a more

cost-effective service strategy. Fundamentally, the service issue is that since not all

our customers are equally profitable nor are our products equally profitable, should

not the highest service be given to key customers and key products? Since we can

assume that money spent on service is a scarce resource then we should look

upon the service decision as a resource allocation issue.

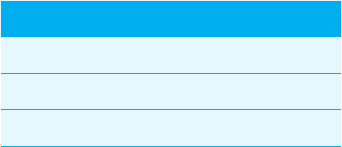

Figure 2.11 shows how a typical company might find its profits varying by cus-

tomer and by product.

0 100%

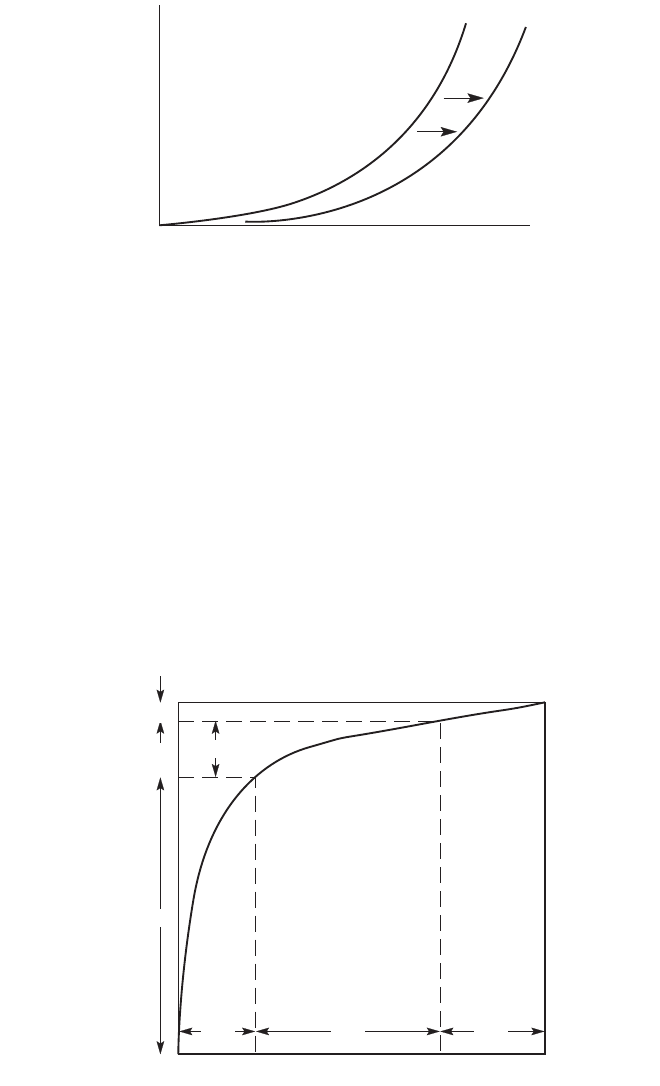

Service level

Cost of service

Figure 2.10 Shifting the costs of service

15%

5%

80%

20%

30%

50%

'A'

'C'

'B'

% Products/customers

% Sales/profits

Figure 2.11 The ‘Pareto’ or 80/20 rule

LO G ISTICS AND CUSTOMER VALU E

47

The curve is traditionally divided into three categories: the top 20 per cent of prod-

ucts and customers by profitability are the ‘A’ category; the next 50 per cent or

so are labelled ‘B’; and the final 30 per cent are category ‘C’. The precise split

between the categories is arbitrary as the shape of the distribution will vary from

business to business and from market to market.

The appropriate measure should be profit rather than sales revenue or volume.

The reason for this is that revenue and volume measures might disguise consider-

able variation in costs. In the case of customers this cost is the ‘cost to serve’, and

we will later suggest an approach to measuring customer profitability. In the case

of product profitability we must also be careful that we are identifying the appropri-

ate service-related costs as they differ by product. One of the problems here is that

conventional accounting methods do not help in the identification of these costs.

What we should be concerned to do at this stage in the analysis is to iden-

tify the contribution to profit that each product (at the individual stock keeping unit

(SKU) level) makes. By contribution we mean the difference between total reve-

nue accruing and the directly attributable costs that attach as the product moves

through the logistics system.

Looking first at differences in product profitability, what use might be made of

the A,B,C categorisation? Firstly it can be used as the basis for classic inventory

control whereby the highest level of service (as represented by safety stock) is pro-

vided for the ‘A’ products, a slightly lower level for the ‘B’ products and lower still

for the ‘Cs’. Thus we might seek to follow the stock holding policy shown below:

Product category Stock availability

A 99%

B 97%

C 90%

Alternatively, and probably to be preferred, we might differentiate the stock holding

by holding the ‘A’ items as close as possible to the customer and the ‘B’ and ‘C’

items further up the supply chain. The savings in stock holding costs achieved by

consolidating the ‘B’ and ‘C’ items as a result of holding them at fewer locations

would normally cover the additional cost of despatching them to the customer by a

faster means of transportation (e.g. overnight delivery).

Perhaps the best way to manage product service levels is to take into account

both the profit contribution and the individual product demand.

We can bring both these measures together in the form of a simple matrix in

Figure 2.12. The matrix can be explained as follows.

Get Logistics and Supply Chain Management, 4th Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.