How to use this Book: Intro

Note

In this section we answer the burning question: “So why DID they put that in a Python book?”

Who is this book for?

If you can answer “yes” to all of these:

-

Do you already know how to program in another programming language?

Do you already know how to program in another programming language? -

Are you looking to add Python to your toolbelt so you can have a much fun coding as all those other Pythonistas?

Are you looking to add Python to your toolbelt so you can have a much fun coding as all those other Pythonistas?Note

“Pythonista”: someone who loves to code with Python

-

Are you a learning-by-getting-your-hands-dirty type of person, preferring to do rather than listen?

Are you a learning-by-getting-your-hands-dirty type of person, preferring to do rather than listen?

This book is for you.

Who should probably back away from this book?

If you can answer “yes” to any of these:

-

Have you never programmed before, and can’t tell your ifs from your loops?

Have you never programmed before, and can’t tell your ifs from your loops? -

Are you a Python expert looking for a concise reference text for the language?

Are you a Python expert looking for a concise reference text for the language? -

Do you hate learning new things? Do you believe no Python book, no matter how good, should make you laugh out loud nor groan at how corny it all is? Would you rather be bored to tears instead?

Do you hate learning new things? Do you believe no Python book, no matter how good, should make you laugh out loud nor groan at how corny it all is? Would you rather be bored to tears instead?

This book is not for you.

Note

[Note from marketing: this book is for anyone with a credit card.]

We know what you’re thinking

“How can this be a serious Python book?”

“What’s with all the graphics?”

“Can I actually learn it this way?”

We know what your brain is thinking

Your brain craves novelty. It’s always searching, scanning, waiting for something unusual. It was built that way, and it helps you stay alive.

So what does your brain do with all the routine, ordinary, normal things you encounter? Everything it can to stop them from interfering with the brain’s real job—recording things that matter. It doesn’t bother saving the boring things; they never make it past the “this is obviously not important” filter.

How does your brain know what’s important? Suppose you’re out for a day hike and a tiger jumps in front of you, what happens inside your head and body?

Neurons fire. Emotions crank up. Chemicals surge.

And that’s how your brain knows…

This must be important! Don’t forget it!

But imagine you’re at home, or in a library. It’s a safe, warm, tiger-free zone. You’re studying. Getting ready for an exam. Or trying to learn some tough technical topic your boss thinks will take a week, ten days at the most.

Just one problem. Your brain’s trying to do you a big favor. It’s trying to make sure that this obviously nonimportant content doesn’t clutter up scarce resources. Resources that are better spent storing the really big things. Like tigers. Like the danger of fire. Like how you should never have posted those “party” photos on your Facebook page. And there’s no simple way to tell your brain, “Hey brain, thank you very much, but no matter how dull this book is, and how little I’m registering on the emotional Richter scale right now, I really do want you to keep this stuff around.”

Metacognition: thinking about thinking

If you really want to learn, and you want to learn more quickly and more deeply, pay attention to how you pay attention. Think about how you think. Learn how you learn.

Most of us did not take courses on metacognition or learning theory when we were growing up. We were expected to learn, but rarely taught to learn.

But we assume that if you’re holding this book, you really want to learn how to design user-friendly websites. And you probably don’t want to spend a lot of time. If you want to use what you read in this book, you need to remember what you read. And for that, you’ve got to understand it. To get the most from this book, or any book or learning experience, take responsibility for your brain. Your brain on this content.

The trick is to get your brain to see the new material you’re learning as Really Important. Crucial to your well-being. As important as a tiger. Otherwise, you’re in for a constant battle, with your brain doing its best to keep the new content from sticking.

So just how DO you get your brain to treat Python like it’s a hungry tiger?

There’s the slow, tedious way, or the faster, more effective way. The slow way is about sheer repetition. You obviously know that you are able to learn and remember even the dullest of topics if you keep pounding the same thing into your brain. With enough repetition, your brain says, “This doesn’t feel important to him, but he keeps looking at the same thing over and over and over, so I suppose it must be.”

The faster way is to do anything that increases brain activity, especially different types of brain activity. The things on the previous page are a big part of the solution, and they’re all things that have been proven to help your brain work in your favor. For example, studies show that putting words within the pictures they describe (as opposed to somewhere else in the page, like a caption or in the body text) causes your brain to try to makes sense of how the words and picture relate, and this causes more neurons to fire. More neurons firing = more chances for your brain to get that this is something worth paying attention to, and possibly recording.

A conversational style helps because people tend to pay more attention when they perceive that they’re in a conversation, since they’re expected to follow along and hold up their end. The amazing thing is, your brain doesn’t necessarily care that the “conversation” is between you and a book! On the other hand, if the writing style is formal and dry, your brain perceives it the same way you experience being lectured to while sitting in a roomful of passive attendees. No need to stay awake.

But pictures and conversational style are just the beginning…

Here’s what WE did:

We used visuals, because your brain is tuned for visuals, not text. As far as your brain’s concerned, a visual really is worth a thousand words. And when text and visuals work together, we embedded the text in the visuals because your brain works more effectively when the text is within the thing the text refers to, as opposed to in a caption or buried in the text somewhere.

We used redundancy, saying the same thing in different ways and with different media types, and multiple senses, to increase the chance that the content gets coded into more than one area of your brain.

We used concepts and visuals in unexpected ways because your brain is tuned for novelty, and we used visuals and ideas with at least some emotional content, because your brain is tuned to pay attention to the biochemistry of emotions. That which causes you to feel something is more likely to be remembered, even if that feeling is nothing more than a little humor, surprise, or interest.

We used a personalized, conversational style, because your brain is tuned to pay more attention when it believes you’re in a conversation than if it thinks you’re passively listening to a presentation. Your brain does this even when you’re reading.

We included more than 80 activities, because your brain is tuned to learn and remember more when you do things than when you read about things. And we made the exercises challenging-yet-doable, because that’s what most people prefer.

We used multiple learning styles, because you might prefer step-by-step procedures, while someone else wants to understand the big picture first, and someone else just wants to see an example. But regardless of your own learning preference, everyone benefits from seeing the same content represented in multiple ways.

We include content for both sides of your brain, because the more of your brain you engage, the more likely you are to learn and remember, and the longer you can stay focused. Since working one side of the brain often means giving the other side a chance to rest, you can be more productive at learning for a longer period of time.

And we included stories and exercises that present more than one point of view, because your brain is tuned to learn more deeply when it’s forced to make evaluations and judgments.

We included challenges, with exercises, and by asking questions that don’t always have a straight answer, because your brain is tuned to learn and remember when it has to work at something. Think about it—you can’t get your body in shape just by watching people at the gym. But we did our best to make sure that when you’re working hard, it’s on the right things. That you’re not spending one extra dendrite processing a hard-to-understand example, or parsing difficult, jargon-laden, or overly terse text.

We used people. In stories, examples, visuals, etc., because, well, because you’re a person. And your brain pays more attention to people than it does to things.

Read Me

This is a learning experience, not a reference book. We deliberately stripped out everything that might get in the way of learning whatever it is we’re working on at that point in the book. And the first time through, you need to begin at the beginning, because the book makes assumptions about what you’ve already seen and learned.

This book is designed to get you quickly up-to-speed.

As you need to know stuff, we teach it. So you won’t find long lists of technical material, so there’s no tables of Python’s operators, nor its operator precedence rules. We don’t cover everything, but we’ve worked really hard to cover the essential material as well as we can, so that you can get Python into your brain quickly and have it stay there. The only assumption we make is that you already know how to program in some other programming language.

You can safely use any release/version of Python 3.

Well… that’s maybe a tiny white lie. You need at least Python 3.6, but as that release first appeared at the end of 2016, it’s unlikely too many people are depending on it day-to-day. FYI: at the time of going to press, Python 3.12 is just around the corner.

The activities are NOT optional.

The exercises and activities are not add-ons; they’re part of the core content of the book. Some of them are to help with memory, some are for understanding, and some will help you apply what you’ve learned. Don’t skip the exercises.

At the end of each chapter you’ll find a crossword created to test your retention of the material presented so far. All of the answers to the clues come from the just-completed chapter. Solutions are provided as each chapter’s last page. Do try to complete each crossword without peeking. Having said that, the crossword puzzles are the only thing you don’t have to do, but they’re good for giving your brain a chance to think about the words and terms you’ve been learning in a different context.

The redundancy is intentional and important.

One distinct difference in a Head First book is that we want you to really get it. And we want you to finish the book remembering what you’ve learned. Most reference books don’t have retention and recall as a goal, but this book is about learning, so you’ll see some of the same concepts come up more than once. That’s on purpose.

The examples are as lean as possible.

Our readers tell us that it’s frustrating to wade through 200 lines of an example looking for the two lines they really need to understand. Most examples in this book are shown within the smallest possible context, so that the part you’re trying to learn is clear and simple. Don’t expect all of the examples to be robust, or even complete—they are written specifically for learning, and aren’t always fully functional (although we do try to ensure this is the case).

We’ve placed all this book’s code and resources on the web so you can use them as needed. Having said that, we do believe there’s lots to learn from typing in the code as you follow along, especially when learning a new (to you) programming language. But for the “just give me the code” type of people out there, here’s this book’s GitHub page: https://github.com/headfirstpython/third

The Brain Power exercises don’t have answers.

For some of them, there is no right answer, and for others, part of the learning experience of the Brain Power activities is for you to decide if and when your answers are right.

Not all Test Drive exercises have answers.

For some exercises, we simply ask that you follow a set of instructions. tWe’ll give you ways to verify if what you did actually worked, but unlike other exercises, there are no right answers!

Let’s install the latest Python

What you do here depends on the platform you’re running, which is assumed to be one of Windows, macOS, or Linux. The good news is that all three platforms run the latest Python. There’s no bad news.

If you are already running release 3 of Python, move to the next page—you’re ready. If you haven’t already installed Python or are using an older version, select the paragraph that follows that applies to you, and read on.

Installing on Windows

The wonderful Python folk at Microsoft work hard to ensure the most-recent release of Python is always available to you via the Windows Store application. Open the Store, search for “Python,” select the most-recent version, then click the Get button. Watch patiently while the progress indicator moves from zero to 100% then, once the install completes, move to the next page—you’re ready.

Note

If you’re running on Windows 11 or later, you might also want to download the new Windows Terminal, which offers a better/nicer command-line experience (should you need it).

Installing on macOS

The latest Macs tend to ship with somewhat older releases of Python. Don’t use these. Instead, head over to Python’s home on the web, https://www.python.org, then click on the “Downloads” option. The latest release of Python 3 should begin to download, as the Python site is smart enough to spot you’re connecting from a Mac. Once the download completes, run the installer that’s waiting for you in your Downloads folder. Click the Next button until there are no more Next buttons to click then, when the install is complete, move to the next page—you’re ready.

Note

There’s no need to remove the older pre-installed releases of Python that come with your Mac. This install will supersede them.

Alternatively, if you’re a user of the Homebrew Package Manager, you’re in luck, as Homebrew has support for the download and installation of the latest Python release.

Installing on Linux

The Head First Coders are a rag-tag team of techies whose job is to keep the Head First Authors on the straight and narrow (no mean feat). The coders love Linux and the Ubuntu distribution, so that’s discussed here.

It should come as no surprise that the latest Ubuntu comes with Python 3 installed and up-to-date. If this is the case, cool, you’re all set, although you may want to use apt to install the python3-pip package, too.

If you are using a Linux distribution other than Ubuntu, use your system’s package manager to install Python 3 into your Linux system. Once done, move to the next page—you’re ready.

Python on its own is not enough

Let’s complete your install with two things: a required backend dependency, as well as a modern, Python-aware text editor. In order to explore, experiment, and learn about Python, you need to install a runtime backend called Jupyter into your Python. As you’ll see in a moment, doing so is straightforward. When it comes to creating Python code, you can use just about any programmer’s editor, but we’re recommending you use a specific one when working through this book’s material: Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code, known the world over as VS Code.

Install the latest Jupyter Notebook backend

Note

Don’t worry, you’ll learn all about what this is used for soon!

Regardless of the operating system you’re running, make sure you’re connected to the internet, open a terminal window, then type:

A veritable slew of status messages whiz by on screen. If you are seeing a message near the end stating everything is “Successfully installed,” then you’re golden. If not, check the Jupyter docs and try again.

Install the latest release of VS Code

Grab your favorite browser and surf on over to the VS Code download page:

https://code.visualstudio.com/Download

Note

There are alternatives to VS Code, but—in our view—VS Code is hard to beat when it comes to this book’s material. And, no, we are *not* part of some global conspiracy to promote Microsoft products!!

Pick the download that matches your environment, then wait for the download to complete. Follow the instructions from the site to install VS Code, then flip the page to learn how to complete your VS Code setup.

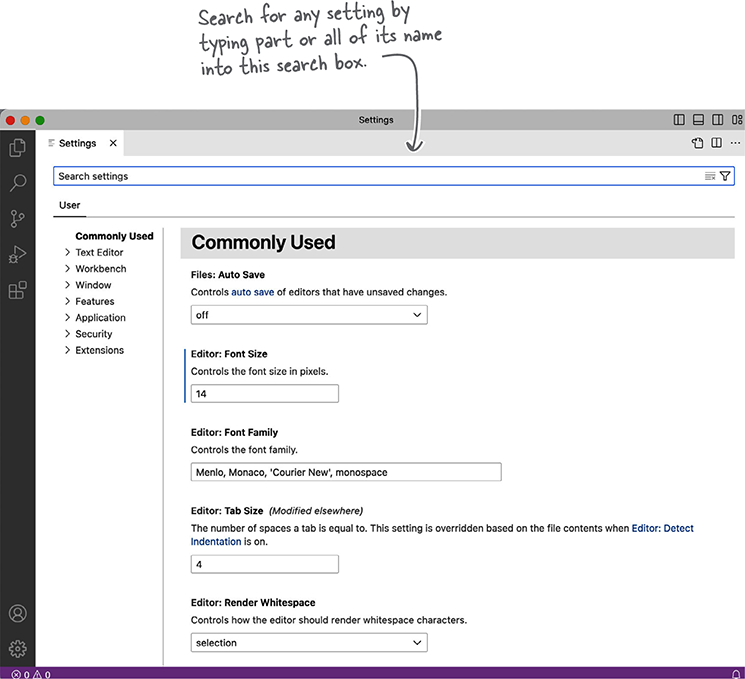

Configure VS Code to your taste

Go ahead and run VS Code for the first time. From the menu, select File, then Preferences, then Settings to access the editor’s settings preferences.

Note

On the Mac, start with the “Code” menu.

You should see something like this:

Until you become familiar with VS Code, you can configure your editor to match the settings preferred by the Head First Coders. Here are the settings used in this book:

-

The indentation guides are switched off.

-

The editor’s color theme is set to Light.

-

The editor minimap is disabled.

-

The editor’s occurrences highlight is switched off.

-

The editor’s render line highlight is set to none.

-

The terminal and text editor’s font size is set to 14.

-

The notebook’s show cell status bar is set to hidden.

-

The editor’s lightbulb is disabled.

Note

You don’t have to use these settings but, if you want to match on your screen what you see in this book, then these adjustments are recommended.

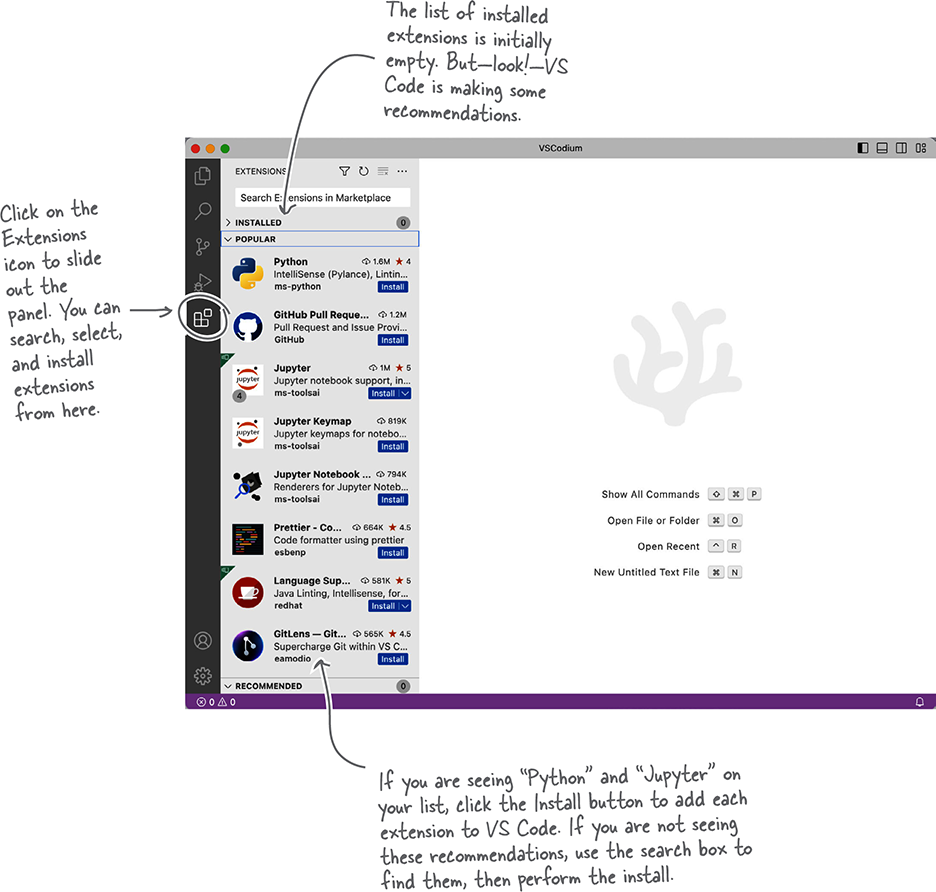

Add two required extensions to VS Code

Whereas you are not obliged to copy the recommended editor setup, you absolutely have to install two VS Code extensions, namely Python and Jupyter.

When you are done adjusting your preferred editor settings, close the Settings tab by clicking the X. Then, to search for, select, and install extensions, click on the Extensions icon to the left of the main VS Code screen:

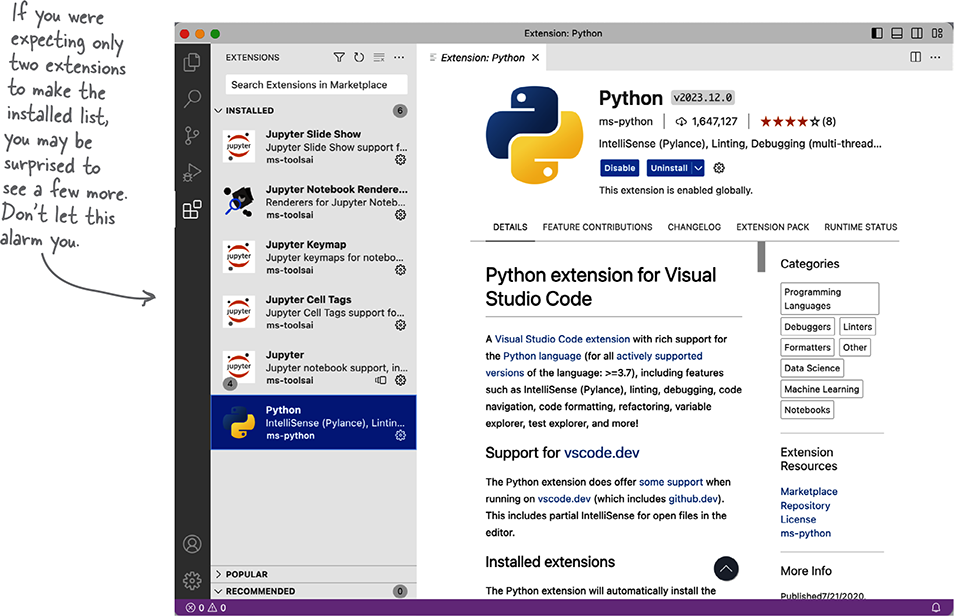

VS Code’s Python support is state-of-the-art

Installing the Python and Jupyter extensions actually results in a few additional VS Code extension installations, as shown here:

These additional extensions enhance VS Code’s support for Python and Jupyter over and above what’s included in the standard extensions. Although you don’t need to know what these extra extensions do (for now), know this: they help turn VS Code into a supercharged Python editor.

With Python 3, Jupyter, and VS Code installed, you’re all set!

Note

Yes, this is a Geek Note about Geek Notes (and we’ll not be having any groan-inducing recursion jokes, thank you).

The Technical Review Team

Meet the Head First Python Technical Review Team!

The Team got to review the Early Release draft of this book and, in doing so, have contributed to making the finished published artifact so much better. Every single one of their comments was read, considered, then decided on or acted upon. They helped to fix the bits that were broken, improved many of our explanations and—in a few places—provided code improvements to some of our embarrassing coding blunders.

Needless to say, anything that’s still wrong is down to us, and us alone.

Our heartfelt thanks to each of these reviewers: your work is very much appreciated.

[And to the mysterious Mark, the tech reviewer who wished to remain anonymous: thank you, too, for your excellent suggestions.]

Acknowledgments

At O’Reilly, I’m going to start with Melissa Potter, this book’s editor.

What an asset Melissa was to this book, although (at times) Melissa may have despaired when things were taking so long. I am so very grateful for Melissa’s guidance and patience throughout, but especially for her keen eye when it came to spotting issues with the book’s flow and my use of language. I’ve always said that, regardless of whether you’re writing a book or not, everybody needs an editor, and I’m delighted mine was Melissa for the third edition.

From a Head First perspective, my thanks to Beth Robson, one of the Series Advisors, for providing detailed comments and suggestions on the Early Release material. It is my hope that the finished book makes Beth smile.

There are a lot of people behind the scenes at O’Reilly. My thanks to them all, but especially to the crew in Production who took my (still amateur) InDesign pages and turned them into a beautifully printed book. Thank you.

At work, my thanks again to my Head of Department Nigel Whyte for continuing to encourage my involvement in these types of writing projects. Also, thanks to my Games Development and Software Development undergrads, as well as my Data Science post-grads, who—over the years—have had versions of this material foisted upon them. It always a pleasure to teach theses groups, and to see them all react positively to learning Python does me no end of good.

At home, my wife Deirdre had to endure yet another book writing project which, as before, seemed to consume every waking moment. Our kids were in their early teens (and younger) when the first edition of this book was written and, now, they’re all through college and off to bigger and better things. Needless to say, I’d be lost without the support and love of my wife and children.

A quick note on the end-of-chapter crosswords: these were generated by David Whitlock’s wonderful genxword program (with some local tweaks by Paul). genxword is written in Python and is, of course, available for download from PyPI.

Get Head First Python, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.