Chapter 1. Breaking the Surface: Dive In: A Quick Dip

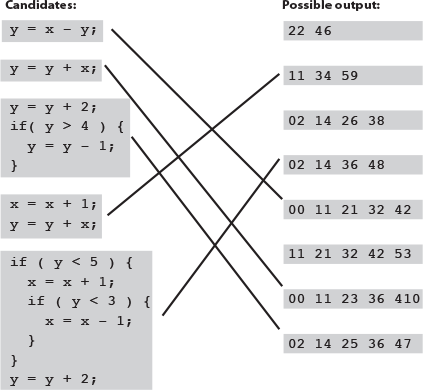

Java takes you to new places. From its humble release to the public as the (wimpy) version 1.02, Java seduced programmers with its friendly syntax, object-oriented features, memory management, and best of allâthe promise of portability. The lure of write-once/run-anywhere is just too strong. A devoted following exploded, as programmers fought against bugs, limitations, and, oh yeah, the fact that it was dog slow. But that was ages ago. If youâre just starting in Java, youâre lucky. Some of us had to walk five miles in the snow, uphill both ways (barefoot), to get even the most trivial application to work. But you, why, you get to ride the sleeker, faster, easier-to-read-and-write Java of today.

What youâll do in Java

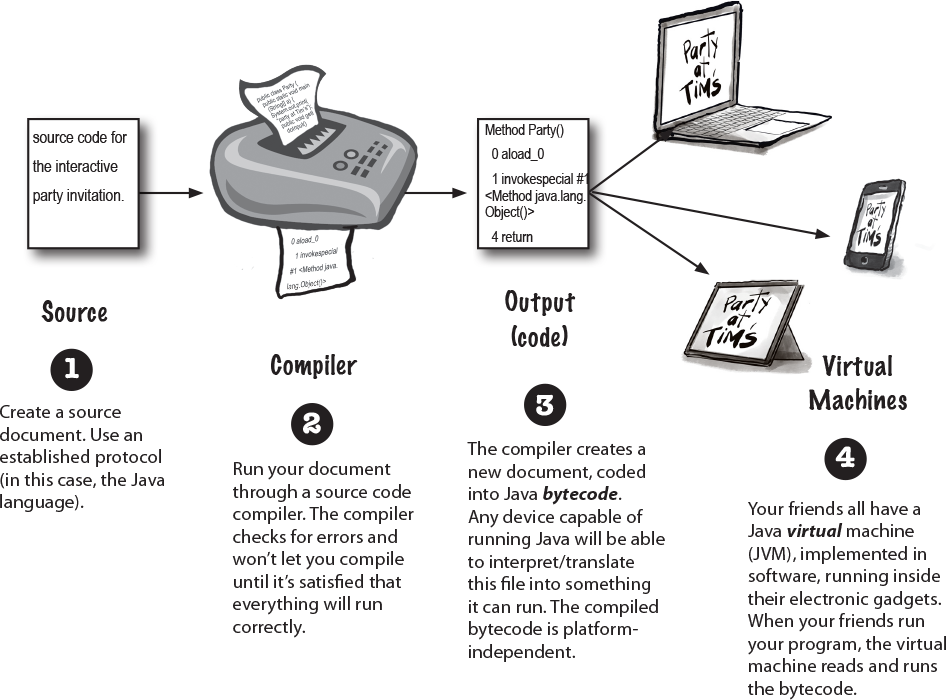

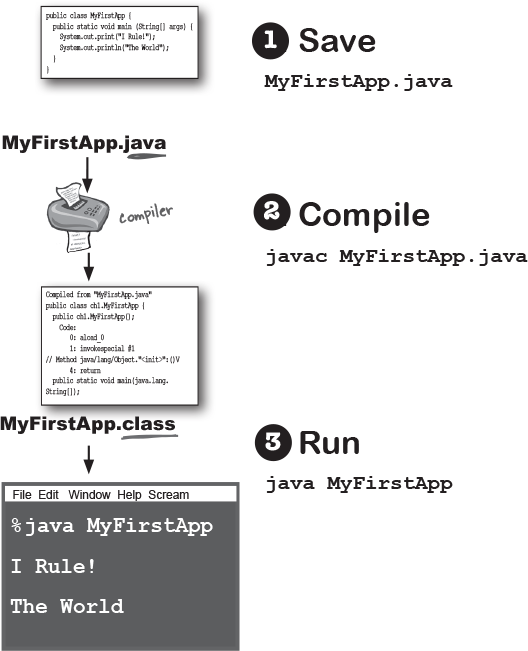

Youâll type a source code file, compile it using the javac compiler, and then run the compiled bytecode on a Java virtual machine.

Note

(Note: this is NOT meant to be a tutorial... youâll be writing real code in a moment, but for now, we just want you to get a feel for how it all fits together.

In other words, the code on this page isnât quite real; donât try to compile it .)

A very brief history of Java

Java was initially released (some would say âescapedâ, on January 23, 1996. Itâs over 25 years old! In the first 25 years, Java as a language evolved, and the Java API grew enormously. The best estimate we have is that over 17 gazillion lines of Java code have been written in the last 25 years. As you spend time programming in Java, you will most certainly come across Java code thatâs quite old, and some thatâs much newer. Java is famous for its backward compatibility, so old code can run quite happily on new JVMs.

In this book weâll generally start off by using older coding styles (remember, youâre likely to encounter such code in the âreal worldâ, and then weâll introduce newer-style code.

In a similar fashion, we will sometimes show you older classes in the Java API, and then show you newer alternatives.

Speed and memory usage

When Java was first released, it was slow. But soon after, the HotSpot VM was created, as were other performance enhancers. While itâs true that Java isnât the fastest language out there, itâs considered to be a very fast languageâalmost as fast as languages like C and Rust, and much faster than most other languages out there.

Java has a magic super-powerâthe JVM. The Java Virtual Machine can optimize your code while itâs running, so itâs possible to create very fast applications without having to write specialized high-performance code.

Butâfull disclosureâcompared to C and Rust, Java uses a lot of memory.

Q: The naming conventions for Javaâs versions are confusing. There was JDK 1.0, and 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, then a jump to J2SE 5.0, then it changed to Java 6, Java 7, and last time I checked, Java was up to Java 18. Whatâs going on?

A: The version numbers have varied a lot over the last 25+ years! We can ignore the letters (J2SE/SE) since these are not really used now. The numbers are a little more involved.

Technically Java SE 5.0 was actually Java 1.5. Same for 6 (1.6), 7 (1.7), and 8 (1.8). In theory, Java is still on version 1.x because new versions are backward compatible, all the way back to 1.0.

However, it was a bit confusing having a version number that was different to the name everyone used, so the official version number from Java 9 onward is just the number, without the â1â prefix; i.e., Java 9 really is version 9, not version 1.9.

In this book weâll use the common convention of 1.0â1.4, then from 5 onward weâll drop the â1â prefix.

Also, since Java 9 was released in September 2017, thereâs been a release of Java every six months, each with a new âmajorâ version number, so we moved very quickly from 9 to 18!

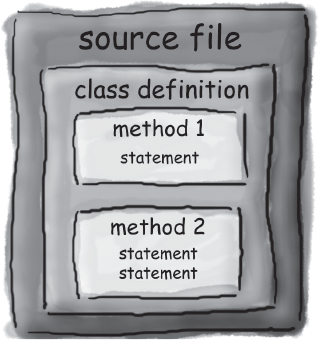

Code structure in Java

In a source file, put a class.

In a class, put methods.

In a method, put statements.

What goes in a source file?

A source code file (with the .java extension) typically holds one class definition. The class represents a piece of your program, although a very tiny application might need just a single class. The class must go within a pair of curly braces.

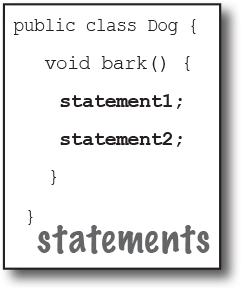

What goes in a class?

A class has one or more methods. In the Dog class, the bark method will hold instructions for how the Dog should bark. Your methods must be declared inside a class (in other words, within the curly braces of the class).

What goes in a method?

Within the curly braces of a method, write your instructions for how that method should be performed. Method code is basically a set of statements, and for now you can think of a method kind of like a function or procedure.

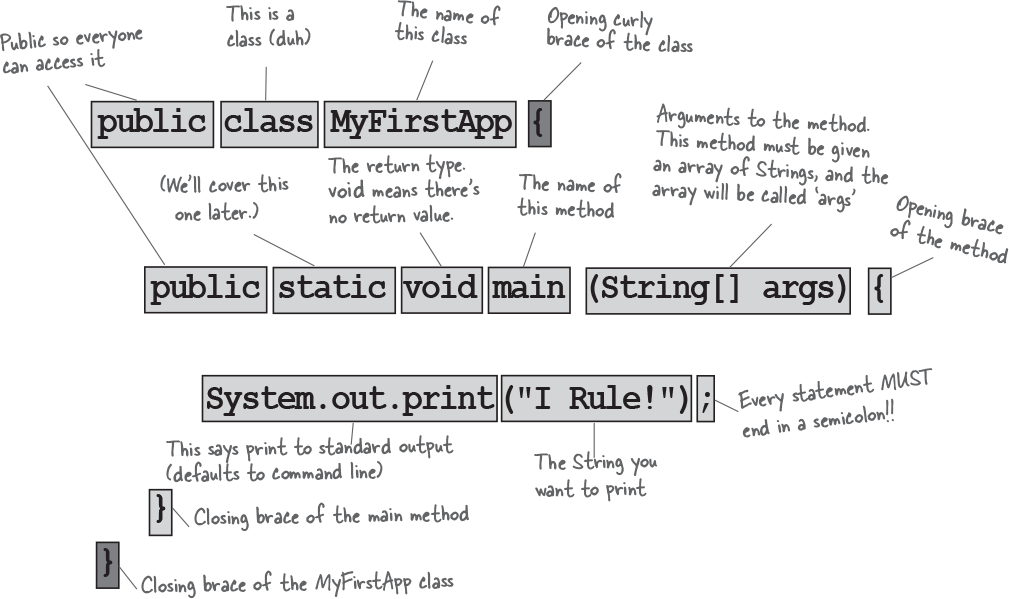

Anatomy of a class

When the JVM starts running, it looks for the class you give it at the command line. Then it starts looking for a specially written method that looks exactly like:

public static void main (String[] args) {

// your code goes here

}

Next, the JVM runs everything between the curly braces { } of your main method. Every Java application has to have at least one class, and at least one main method (not one main per class; just one main per application).

Donât worry about memorizing anything right now... this chapter is just to get you started.

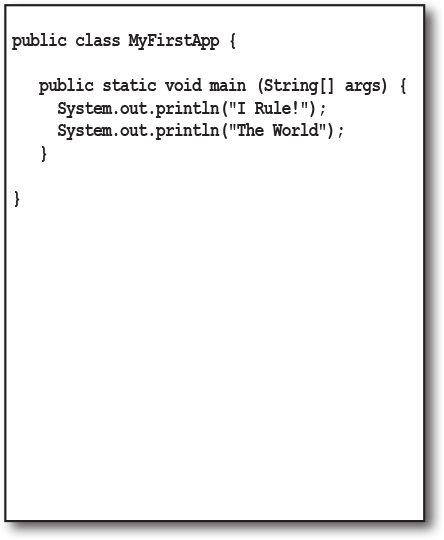

Writing a class with a main()

In Java, everything goes in a class. Youâll type your source code file (with a .java extension), then compile it into a new class file (with a .class extension). When you run your program, youâre really running a class.

Running a program means telling the Java Virtual Machine (JVM) to âLoad the MyFirstApp class, then start executing its main() method. Keep running âtil all the code in main is finished.â

In Chapter 2, A Trip to Objectville, we go deeper into the whole class thing, but for now, the only question you need to ask is, how do I write Java code so that it will run? And it all begins with main().

The main() method is where your program starts running.

No matter how big your program is (in other words, no matter how many classes your program uses), thereâs got to be a main() method to get the ball rolling.

Tonightâs Talk: The compiler and the JVM battle over the question, âWhoâs more important?â

| The Java Virtual Machine | The Compiler |

|---|---|

| What, are you kidding? HELLO. I am Java. Iâm the one who actually makes a program run. The compiler just gives you a file. Thatâs it. Just a file. You can print it out and use it for wallpaper, kindling, lining the bird cage, whatever, but the file doesnât do anything unless Iâm there to run it. | |

| I donât appreciate that tone. | |

| And thatâs another thing, the compiler has no sense of humor. Then again, if you had to spend all day checking nitpicky little syntax violations... | |

| Excuse me, but without me, what exactly would you run? Thereâs a reason Java was designed to use a bytecode compiler, for your information. If Java were a purely interpreted language, whereâat runtimeâthe virtual machine had to translate straight-from-a-text-editor source code, a Java program would run at a ludicrously glacial pace. | |

| Iâm not saying youâre, like, completely useless. But really, what is it that you do? Seriously. I have no idea. A programmer could just write bytecode by hand, and Iâd take it. You might be out of a job soon, buddy. | |

| Excuse me, but thatâs quite an ignorant (not to mention arrogant) perspective. While it is true thatÂâtheoreticallyâyou can run any properly formatted bytecode even if it didnât come out of a Java compiler, in practice thatâs absurd. A programmer writing bytecode by hand is like painting pictures of your vacation instead of taking photosâsure, itâs an art, but most people prefer to use their time differently. And I would appreciate it if you would not refer to me as âbuddy.â | |

| (I rest my case on the humor thing.) But you still didnât answer my question, what do you actually do? | |

| Remember that Java is a strongly typed language, and that means I canât allow variables to hold data of the wrong type. This is a crucial safety feature, and Iâm able to stop the vast majority of violations before they ever get to you. And I alsoâ | |

| But some still get through! I can throw ClassCastExceptions and sometimes I get people trying to put the wrong type of thing in an array that was declared to hold something else, andâ | |

| Excuse me, but I wasnât done. And yes, there are some datatype exceptions that can emerge at runtime, but some of those have to be allowed to support one of Javaâs other important featuresâdynamic binding. At runtime, a Java program can include new objects that werenât even known to the original programmer, so I have to allow a certain amount of flexibility. But my job is to stop anything that would neverâcould neverâsucceed at runtime. Usually I can tell when something wonât work, for example, if a programmer accidentally tried to use a Button object as a Socket connection, I would detect that and thus protect them from causing harm at runtime. | |

| OK. Sure. But what about security? Look at all the security stuff I do, and youâre like, what, checking for semicolons? Oooohhh big security risk! Thank goodness for you! | |

| Excuse me, but I am the first line of defense, as they say. The datatype violations I previously described could wreak havoc in a program if they were allowed to manifest. I am also the one who prevents access violations, such as code trying to invoke a private method, or change a method thatâfor security reasonsâmust never be changed. I stop people from touching code theyâre not meant to see, including code trying to access another classâ critical data. It would take hours, perhaps days even, to describe the significance of my work. | |

| Whatever. I have to do that same stuff too, though, just to make sure nobody snuck in after you and changed the bytecode before running it. | |

| Of course, but as I indicated previously, if I didnât prevent what amounts to perhaps 99% of the potential problems, you would grind to a halt. And it looks like weâre out of time, so weâll have to revisit this in a later chat. | |

| Oh, you can count on it. Buddy. |

What can you say in the main method?

Once youâre inside main (or any method), the fun begins. You can say all the normal things that you say in most programming languages to make the computer do something.

Your code can tell the JVM to:

![]() do something

do something

Statements: declarations, assignments, method calls, etc.

int x = 3;

String name = "Dirk";

x = x * 17;

System.out.print("x is " + x);

double d = Math.random();

// this is a comment

![]() do something again and again

do something again and again

Loops: for and while

while (x > 12) {

x = x - 1;

}

for (int i = 0; i < 10; i = i + 1) {

System.out.print("i is now " + i);

}

![]() do something under this condition

do something under this condition

Branching: if/else tests

if (x == 10) {

System.out.print("x must be 10");

} else {

System.out.print("x isn't 10");

}

if ((x < 3) && (name.equals("Dirk"))) {

System.out.println("Gently");

}

System.out.print("this line runs no matter what");

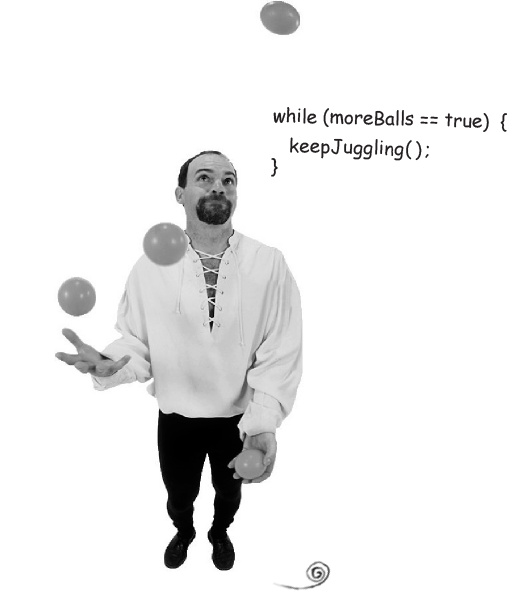

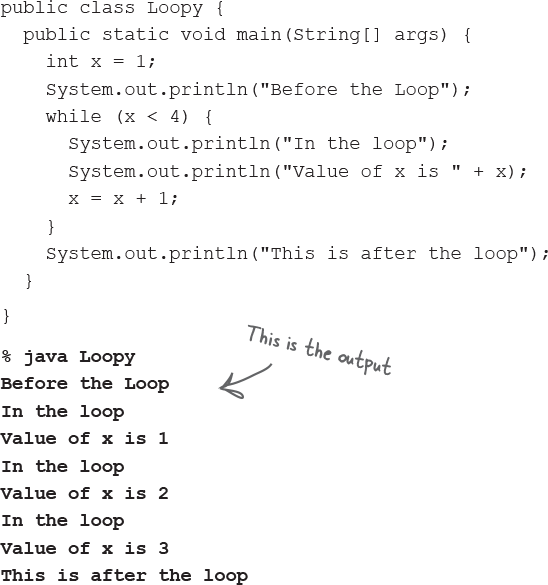

Looping and looping and...

Java has a lot of looping constructs: while, do-while, and for, being the oldest. Youâll get the full loop scoop later in the book, but not right now. Letâs start with while.

The syntax (not to mention logic) is so simple youâre probably asleep already. As long as some condition is true, you do everything inside the loop block. The loop block is bounded by a pair of curly braces, so whatever you want to repeat needs to be inside that block.

The key to a loop is the conditional test. In Java, a conditional test is an expression that results in a boolean valueÂâin other words, something that is either true or false.

If you say something like, âWhile iceCreamInTheTub is true, keep scooping,â you have a clear boolean test. There either is ice cream in the tub or there isnât. But if you were to say, âWhile Bob keep scooping,â you donât have a real test. To make that work, youâd have to change it to something like, âWhile Bob is snoring...â or âWhile Bob is not wearing plaid...â

Simple boolean tests

You can do a simple boolean test by checking the value of a variable, using a comparison operator like:

< (less than)

> (greater than)

== (equality) (yes, thatâs two equals signs)

Notice the difference between the assignment operator (a single equals sign) and the equals operator (two equals signs). Lots of programmers accidentally type = when they want ==. (But not you.)

int x = 4; // assign 4 to x

while (x > 3) {

// loop code will run because

// x is greater than 3

x = x - 1; // or weâd loop forever

}

int z = 27; //

while (z == 17) {

// loop code will not run because

// z is not equal to 17

}

Example of a while loop

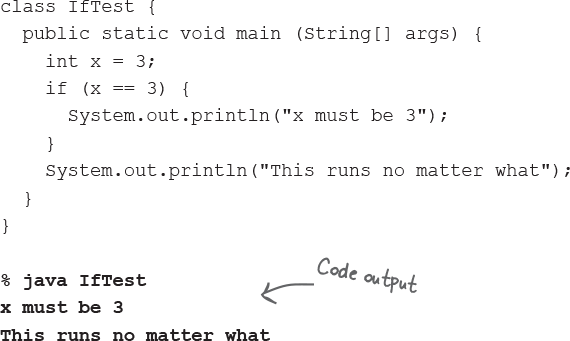

Conditional branching

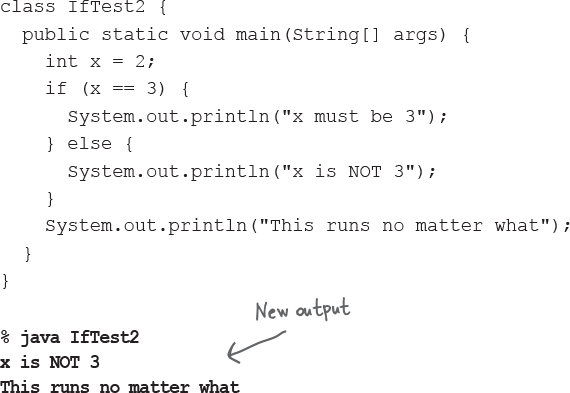

In Java, an if test is basically the same as the boolean test in a while loopâexcept instead of saying, âwhile thereâs still chocolate,â youâll say, âif thereâs still chocolate...â

The preceding code executes the line that prints âx must be 3â only if the condition (x is equal to 3) is true. Regardless of whether itâs true, though, the line that prints âThis runs no matter whatâ will run. So depending on the value of x, either one statement or two will print out.

But we can add an else to the condition so that we can say something like, âIf thereâs still chocolate, keep coding, else (otherwise) get more chocolate, and then continue on...â

Coding a serious business application

Letâs put all your new Java skills to good use with something practical. We need a class with a main(), an int and a String variable, a while loop, and an if test. A little more polish, and youâll be building that business back-end in no time. But before you look at the code on this page, think for a moment about how you would code that classic childrenâs favorite, â10 green bottles.â

public class BottleSong {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int bottlesNum = 10;

String word = "bottles";

while (bottlesNum > 0) {

if (bottlesNum == 1) {

word = "bottle"; // singular, as in ONE bottle.

}

System.out.println(bottlesNum + " green " + word + ", hanging on the wall");

System.out.println(bottlesNum + " green " + word + ", hanging on the wall");

System.out.println("And if one green bottle should accidentally fall,");

bottlesNum = bottlesNum - 1;

if (bottlesNum > 0) {

System.out.println("There'll be " + bottlesNum +

" green " + word + ", hanging on the wall");

} else {

System.out.println("There'll be no green bottles, hanging on the wall");

} // end else

} // end while loop

} // end main method

} // end class

Thereâs still one little flaw in our code. It compiles and runs, but the output isnât 100% perfect. See if you can spot the flaw and fix it.

Monday morning at Bobâs Java-enabled house

Bobâs alarm clock rings at 8:30 Monday morning, just like every other weekday. But Bob had a wild weekend and reaches for the SNOOZE button. And thatâs when the action starts, and the Java-enabled appliances come to life...

First, the alarm clock sends a message to the coffee maker âHey, the geekâs sleeping in again, delay the coffee 12 minutes.â

The coffee maker sends a message to the MotorolaTM toaster, âHold the toast, Bobâs snoozing.â

The alarm clock then sends a message to Bobâs Android, âCall Bobâs 9 oâclock and tell him weâre running a little late.â

Finally, the alarm clock sends a message to Samâs (Sam is the dog) wireless collar, with the too-familiar signal that means, âGet the paper, but donât expect a walk.â

A few minutes later, the alarm goes off again. And again Bob hits SNOOZE and the appliances start chattering. Finally, the alarm rings a third time. But just as Bob reaches for the snooze button, the clock sends the âjump and barkâ signal to Samâs collar. Shocked to full consciousness, Bob rises, grateful that his Java skills, and spontaneous internet shopping purchases, have enhanced the daily routines of his life.

His toast is toasted.

His coffee steams.

His paper awaits.

Just another wonderful morning in The Java-Enabled House.

OK, so the bottle song wasnât really a serious business application. Still need something practical to show the boss? Check out the Phrase-O-Matic code.

Note

Note: when you type this into an editor, let the code do its own word/line-wrapping! Never hit the return key when youâre typing a String (a thing between âquotesâ or it wonât compile. So the hyphens you see on this page are real, and you can type them, but donât hit the return key until AFTER youâve closed a String.

public class PhraseOMatic {

public static void main (String[] args) {

// make three sets of words to choose from. Add your own!

String[] wordListOne = {"agnostic", "opinionated",

"voice activated", "haptically driven", "extensible",

"reactive", "agent based", "functional", "AI enabled",

"strongly typed"};

String[] wordListTwo = {"loosely coupled", "six sigma",

"asynchronous", "event driven", "pub-sub", "IoT", "cloud

native", "service oriented", "containerized", "serverless",

"microservices", "distributed ledger"};

String[] wordListThree = {"framework", "library",

"DSL", "REST API", "repository", "pipeline", "service

mesh", "architecture", "perspective", "design",

"orientation"};

// make three sets of words to choose from. Add your own!

String[] wordListOne = {"agnostic", "opinionated",

"voice activated", "haptically driven", "extensible",

"reactive", "agent based", "functional", "AI enabled",

"strongly typed"};

String[] wordListTwo = {"loosely coupled", "six sigma",

"asynchronous", "event driven", "pub-sub", "IoT", "cloud

native", "service oriented", "containerized", "serverless",

"microservices", "distributed ledger"};

String[] wordListThree = {"framework", "library",

"DSL", "REST API", "repository", "pipeline", "service

mesh", "architecture", "perspective", "design",

"orientation"};

// find out how many words are in each list

int oneLength = wordListOne.length;

int twoLength = wordListTwo.length;

int threeLength = wordListThree.length;

// find out how many words are in each list

int oneLength = wordListOne.length;

int twoLength = wordListTwo.length;

int threeLength = wordListThree.length;

// generate three random numbers

java.util.Random randomGenerator = new java.util.Random();

int rand1 = randomGenerator.nextInt(oneLength);

int rand2 = randomGenerator.nextInt(twoLength);

int rand3 = randomGenerator.nextInt(threeLength);

// generate three random numbers

java.util.Random randomGenerator = new java.util.Random();

int rand1 = randomGenerator.nextInt(oneLength);

int rand2 = randomGenerator.nextInt(twoLength);

int rand3 = randomGenerator.nextInt(threeLength);

// now build a phrase

String phrase = wordListOne[rand1] + " " +

wordListTwo[rand2] + " " + wordListThree[rand3];

// now build a phrase

String phrase = wordListOne[rand1] + " " +

wordListTwo[rand2] + " " + wordListThree[rand3];

// print out the phrase

System.out.println("What we need is a " + phrase);

}

}

// print out the phrase

System.out.println("What we need is a " + phrase);

}

}

Phrase-O-Matic

How it works

In a nutshell, the program makes three lists of words, then randomly picks one word from each of the three lists, and prints out the result. Donât worry if you donât understand exactly whatâs happening in each line. For goodness sake, youâve got the whole book ahead of you, so relax. This is just a quick look from a 30,000-foot outside-the-box targeted leveraged paradigm.

1. The first step is to create three String arraysâthe containers that will hold all the words. Declaring and creating an array is easy; hereâs a small one:

String[] pets = {"Fido", "Zeus", "Bin"};

Each word is in quotes (as all good Strings must be) and separated by commas.

2. For each of the three lists (arrays), the goal is to pick a random word, so we have to know how many words are in each list. If there are 14 words in a list, then we need a random number between 0 and 13 (Java arrays are zero-based, so the first word is at position 0, the second word position 1, and the last word is position 13 in a 14-element array). Quite handily, a Java array is more than happy to tell you its length. You just have to ask. In the pets array, weâd say:

int x = pets.length;

and x would now hold the value 3.

3. We need three random numbers. Java ships out of the box with several ways to generate random numbers, including java.util.Random (we will see later why this class name is prefixed with java.util). The nextInt() method returns a random number between 0 and some-number-we-give-it, not including the number that we give it. So weâll give it the number of elements (the array length) in the list weâre using. Then we assign each result to a new variable. We could just as easily have asked for a random number between 0 and 5, not including 5:

int x = randomGenerator.nextInt(5);

4. Now we get to build the phrase, by picking a word from each of the three lists and smooshing them together (also inserting spaces between words). We use the â+â operator, which concatenates (we prefer the more technical smooshes) the String objects together. To get an element from an array, you give the array the index number (position) of the thing you want by using:

String s = pets[0]; // s is now the String "Fido" s = s + " " + "is a dog"; // s is now "Fido is a dog"

5. Finally, we print the phrase to the command line and...voil...! Weâre in marketing.

Exercise

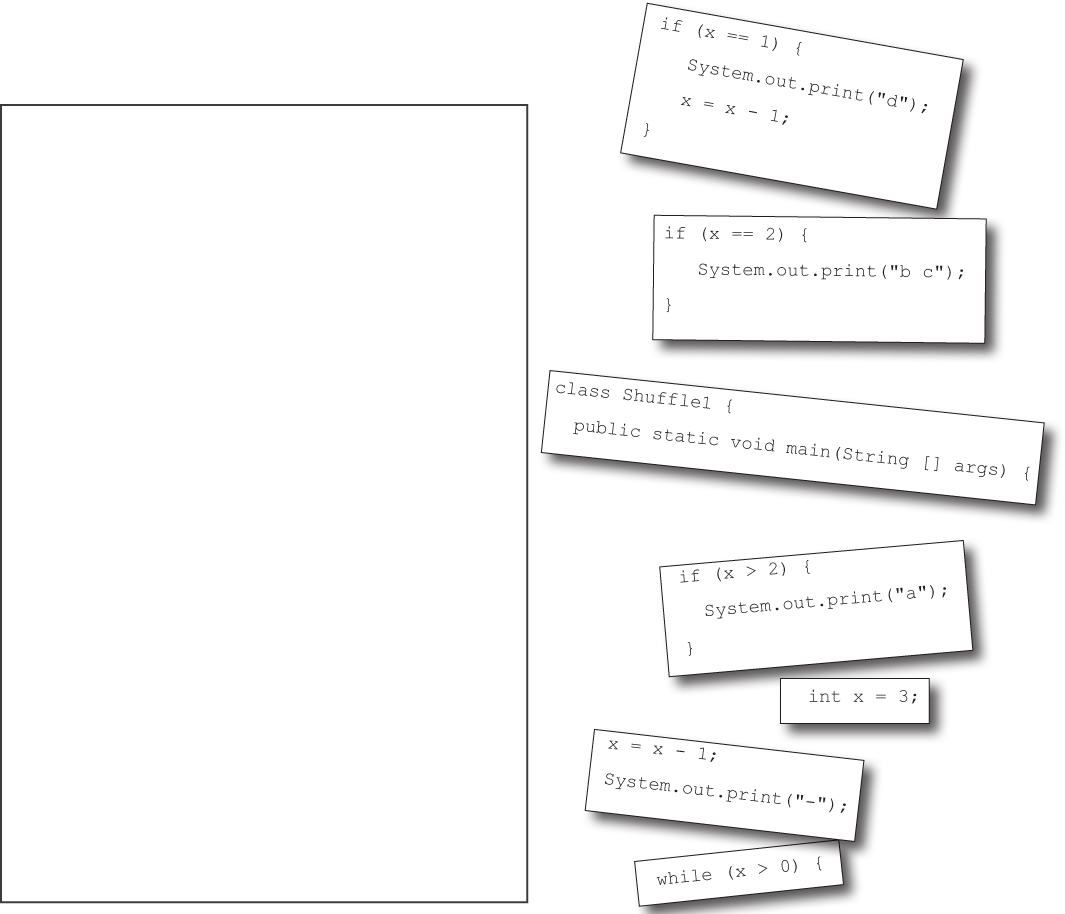

Code Magnets

A working Java program is all scrambled up on the fridge. Can you rearrange the code snippets to make a working Java program that produces the output listed below? Some of the curly braces fell on the floor and they were too small to pick up, so feel free to add as many of those as you need!

Output:

![]() Answers in âExercise Solutionsâ.

Answers in âExercise Solutionsâ.

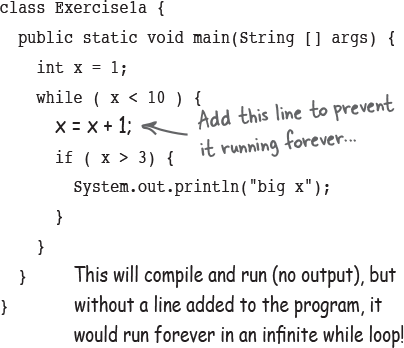

BE the Compiler

Each of the Java files on this page represents a complete source file. Your job is to play compiler and determine whether each of these files will compile. If they wonât compile, how would you fix them?

![]() Answers in âExercise Solutionsâ.

Answers in âExercise Solutionsâ.

A

class Exercise1a {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 1;

while (x < 10) {

if (x > 3) {

System.out.println("big x");

}

}

}

}

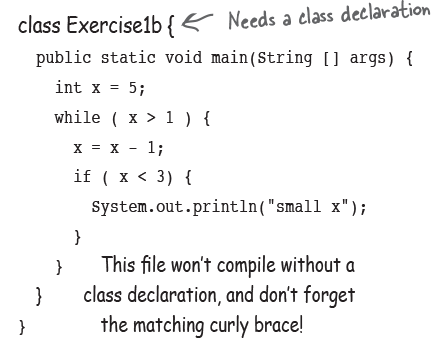

B

public static void main(String [] args) {

int x = 5;

while ( x > 1 ) {

x = x - 1;

if ( x < 3) {

System.out.println("small x");

}

}

}

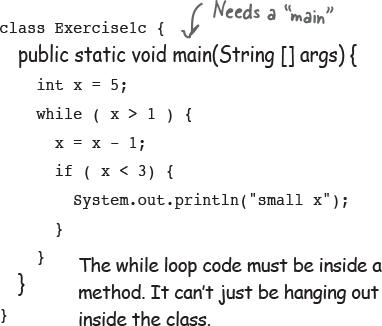

C

class Exercise1c {

int x = 5;

while (x > 1) {

x = x - 1;

if (x < 3) {

System.out.println("small x");

}

}

}

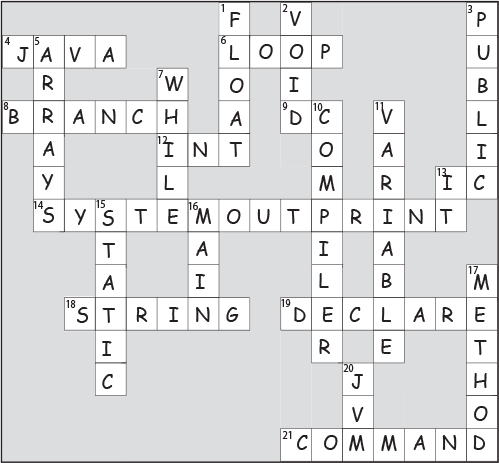

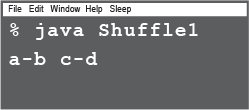

JavaCross

Letâs give your right brain something to do.

Itâs your standard crossword, but almost all of the solution words are from Chapter 1. Just to keep you awake, we also threw in a few (non-Java) words from the high-tech world.

Across

4. Command line invoker

6. Back again?

8. Canât go both ways

9. Acronym for your laptopâs power

12. Number variable type

13. Acronym for a chip

14. Say something

18. Quite a crew of characters

19. Announce a new class or method

21. Whatâs a prompt good for?

Down

1. Not an integer (or _____ your boat)

2. Come back empty-handed

3. Open house

5. âThingsâ holders

7. Until attitudes improve

10. Source code consumer

11. Canât pin it down

13. Department for programmers and operations

15. Shocking modifier

16. Just gotta have one

17. How to get things done

20. Bytecode consumer

![]() Answers in âJavaCrossâ.

Answers in âJavaCrossâ.

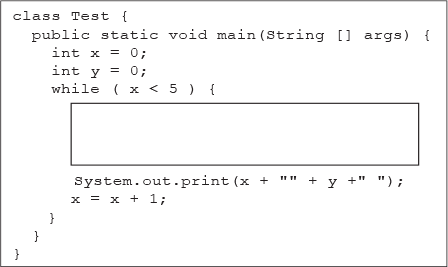

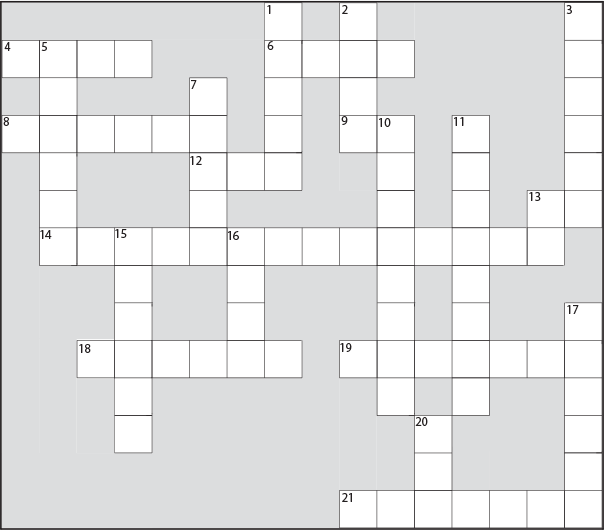

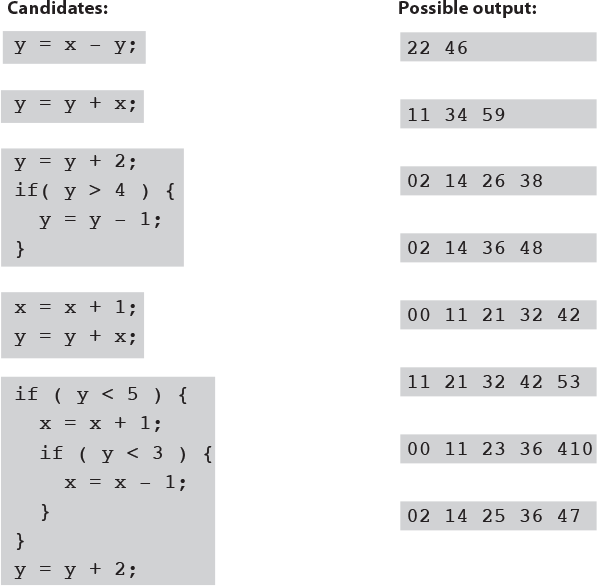

Mixed Messages

A short Java program is listed below. One block of the program is missing. Your challenge is to match the candidate block of code (on the left) with the output that youâd see if the block were inserted. Not all the lines of output will be used, and some of the lines of output might be used more than once. Draw lines connecting the candidate blocks of code with their matching command-line output.

Note

Match each candidate with one of the possible outputs

![]() Answers in âMixed Messagesâ.

Answers in âMixed Messagesâ.

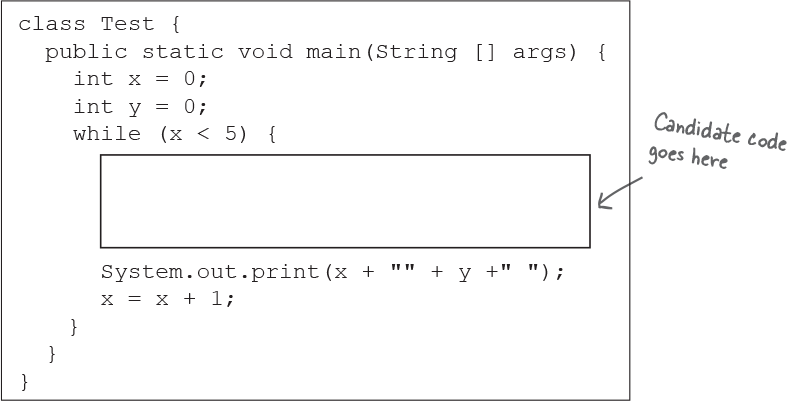

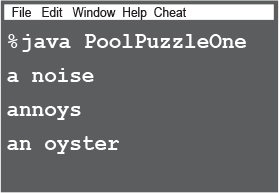

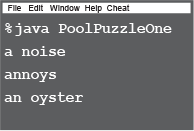

Pool Puzzle

Your job is to take code snippets from the pool and place them into the blank lines in the code. You may not use the same snippet more than once, and you wonât need to use all the snippets. Your goal is to make a class that will compile and run and produce the output listed. Donât be fooledâthis oneâs harder than it looks.

![]() Answers in âPool Puzzleâ.

Answers in âPool Puzzleâ.

Output

Note

Note: Each snippet from the pool can be used only once!

class PoolPuzzleOne {

public static void main(String [] args) {

int x = 0;

while ( __________ ) {

_____________________________

if ( x < 1 ) {

___________________________

}

_____________________________

if ( __________ ) {

____________________________

___________

}

if ( x == 1 ) {

____________________________

}

if ( ___________ ) {

____________________________

}

System.out.println();

____________

}

}

}

Exercise Solutions

Sharpen your pencil

(from âthere are no Dumb Questionsâ)

public class DooBee {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 1;

while (x < 3) {

System.out.print("Doo");

System.out.print("Bee");

x = x + 1;

}

if (x == 3) {

System.out.print("Do");

}

}

}

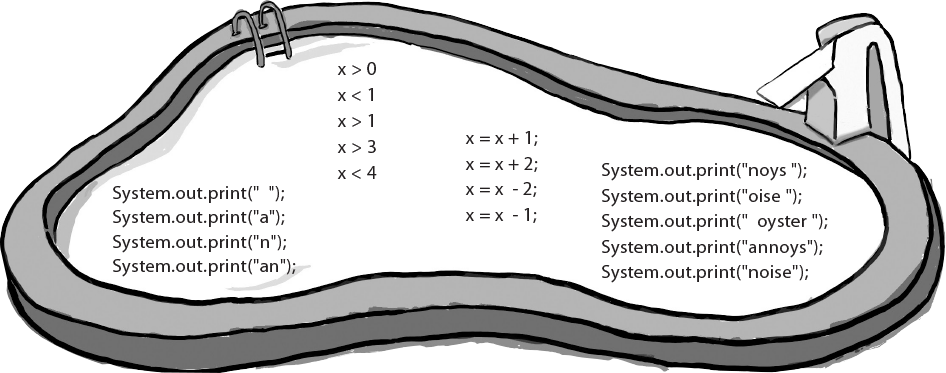

Code Magnets

(from âCode Magnetsâ)

class Shuffle1 {

public static void main(String[] args) {

int x = 3;

while (x > 0) {

if (x > 2) {

System.out.print("a");

}

x = x - 1;

System.out.print("-");

if (x == 2) {

System.out.print("b c");

}

if (x == 1) {

System.out.print("d");

x = x - 1;

}

}

}

}

Pool Puzzle

(from âPool Puzzleâ)

class PoolPuzzleOne {

public static void main(String [] args) {

int x = 0;

while ( x < 4 ) {

System.out.print("a");

if ( x < 1 ) {

System.out.print(" ");

}

System.out.print("n");

if ( x > 1 ) {

System.out.print(" oyster");

x = x + 2;

}

if ( x == 1 ) {

System.out.print("noys");

}

if ( x < 1 ) {

System.out.print("oise");

}

System.out.println();

x = x + 1;

}

}

}

Get Head First Java, 3rd Edition now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.