Chapter 1. The Value Exchange System

Companies end up in the build trap when they misunderstand value. Instead of associating value with the outcomes they want to create for their businesses and customers, they measure value by the number of things they produce. Marquetly was a clear example of this when the leaders celebrated the 10 features the company shipped in a single month, but none of those features achieved their goals.

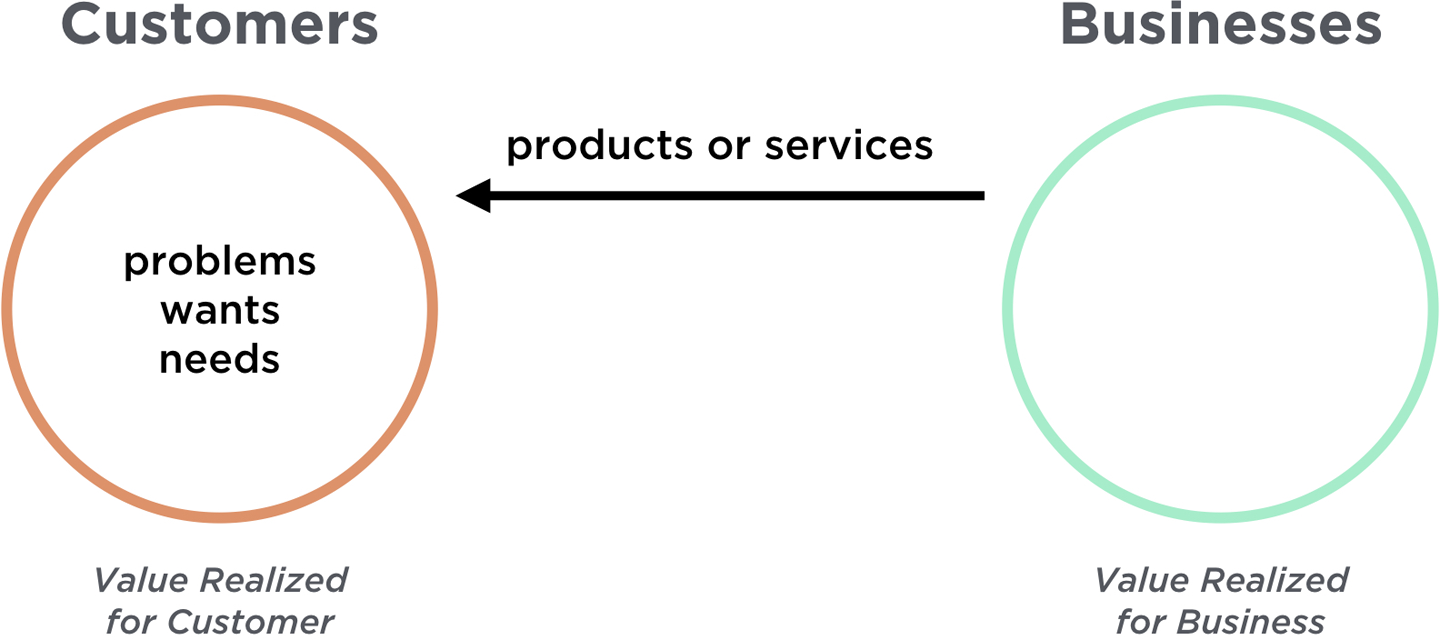

Let’s go back to the basics to determine what true value is. Fundamentally, companies operate on a value exchange, as shown in Figure 1-1.

Figure 1-1. The value exchange

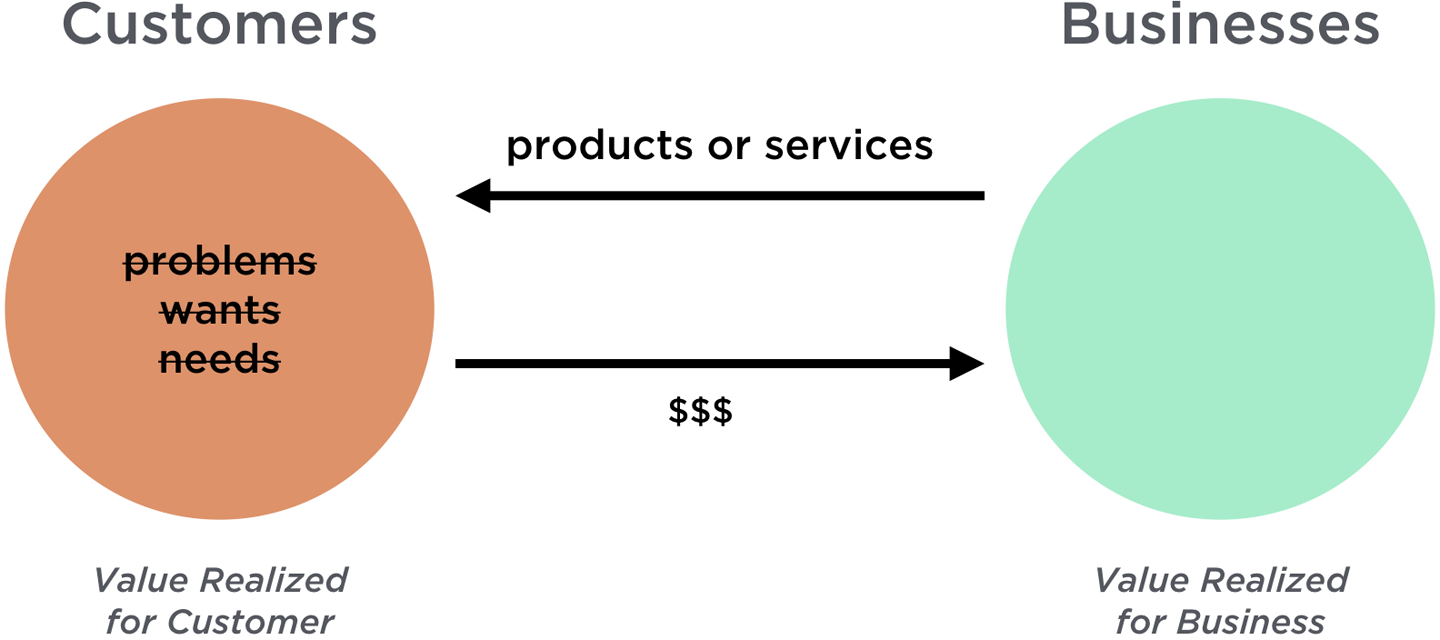

On one side, customers and users have problems, wants, and needs. On the other side are businesses that create products or services to resolve those problems and to fulfill those wants and needs. The customer realizes value only when these problems are resolved and these wants and needs are fulfilled. Then, and only then, do they provide value back to the business, as shown in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. The value exchange realized

Value, from a business perspective, is pretty straightforward. It’s something that can fuel your business: money, data, knowledge capital, or promotion. Every feature you build and any initiative you take as a company should result in some outcome that is tied back to that business value.

But value can be difficult to measure and to measure well from a customer or user perspective. Products and services are not inherently valuable. It’s what they do for the customer or user that has the value—solving a problem, for example, or fulfilling a desire or need. Doing this repeatedly and reliably is what guides a company to success.

When companies do not understand their customers’ or users’ problems well, they cannot possibly define value for them. Instead of doing the work to learn this information about customers, they create a proxy that is easy to measure. “Value” becomes the quantity of features that are delivered, and, as a result, the number of features shipped becomes the primary metric of success.

These companies then motivate their employees and judge them for success with the same proxies. Developers are rewarded for writing tons of functional code. Designers are rewarded for fine-tuning interactions and creating pixel-perfect designs. Product managers are rewarded for writing long specification documents or, in an Agile world, creating extensive backlogs. The team is rewarded for shipping massive quantities of features. This way of thinking is detrimental yet pervasive.

I once worked with a company that made a data platform for enterprise companies. It had a total of 30 features, with about 40 more on the backlog, when I came in. When I measured the customer use of those existing features, we discovered people used only 2% of them consistently. And yet, development was underway to add more, instead of trying to reevaluate what they already had.

How did they end up there? A few reasons, and these apply to many companies stuck in the build trap. The company was playing a game of catch-up—trying to fast-follow its competitors on every feature it released. It didn’t even know whether these features were working out well for their competitors, but management insisted on parity. This is the same trap Google+ fell into with Facebook—never differentiating enough, just copying.

The company also overpromised during the sales process, giving customers whatever it took to get the contract signed. The result was a ton of one-off features that satisfied the needs of only one client, rather than a strategic choice to build what would scale for many clients.

Instead of analyzing how each of these features provided unique value to its customers and moving the company strategy forward, the organization was stuck in reactive mode. It was not building with intent. And yet, it thought of itself as a successful company because it had a million features to talk about at user conferences. The company lost sight of what made its product attractive to customers—what made the company special.

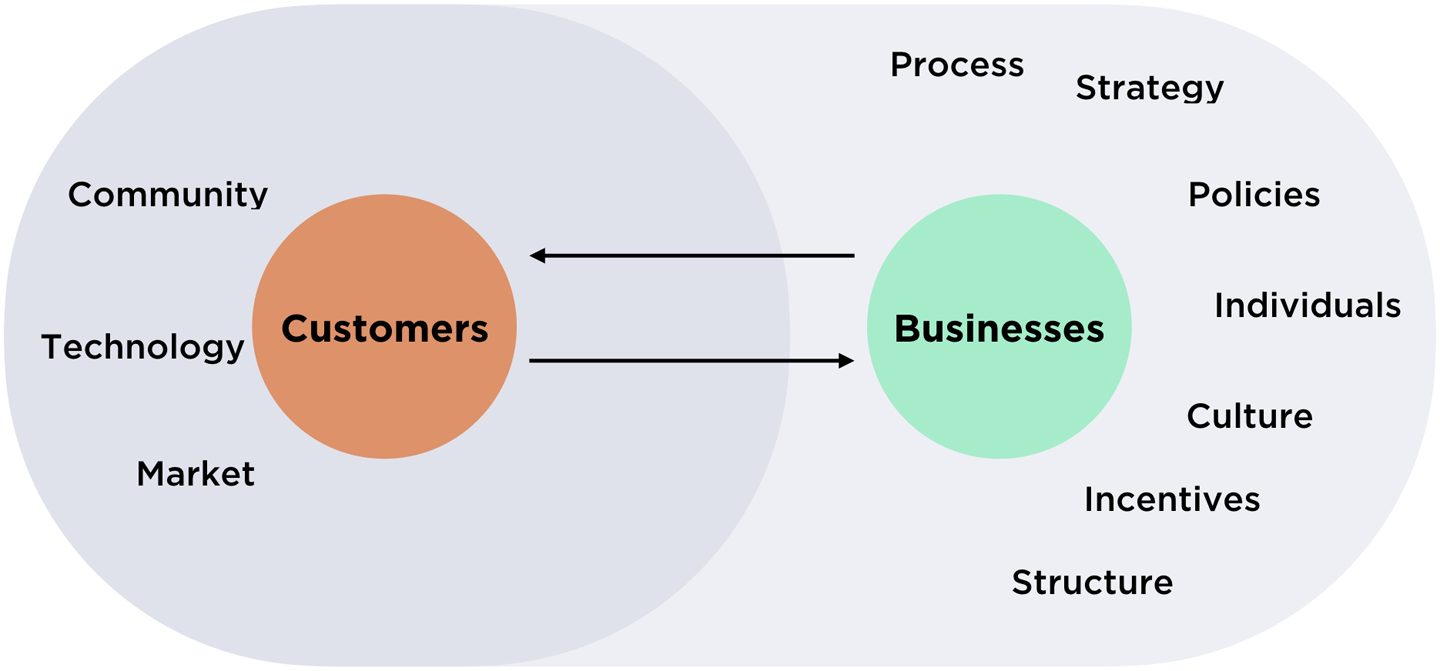

You have to get to know your customers and users, deeply understanding their needs, to determine which products and services will fulfill needs both from the customer side and the business side. This is how you develop the Value Exchange System, as illustrated in Figure 1-3. To gain this understanding, companies need to get their employees closer to their customers and users so that they can learn from them, which means having the right policies throughout the organization to enable this.

Figure 1-3. The Value Exchange System

Policies are one example of a constraint that affects this value exchange. This system is constrained by influences on both sides, as we saw in Figure 1-2.

Get Escaping the Build Trap now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.