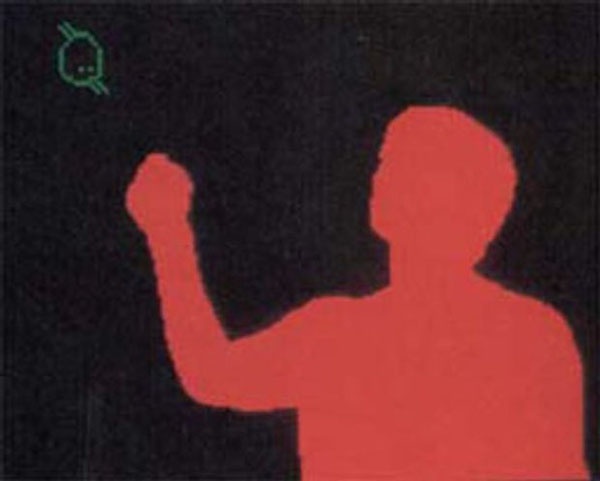

Figure 1-4. How the computer sees us. With traditional interfaces, humans are reduced to an eye and a finger. Gestural interfaces allow for fuller use of the human body to trigger system responses. Courtesy Dan O'Sullivan and Tom Igoe.

As The Clapper illustrates, gestural interfaces are really nothing new. In one sense, everything we do with digital devices requires some sort of physical action to create a digital response. You press a key, and a letter or number appears on-screen. You move a mouse, and a pointer scurries across the screen.

What is different, though, between gestural interfaces and traditional interfaces is simply this: gestural interfaces have a much wider range of actions with which to manipulate a system. In addition to being able to type, scroll, point and click, and perform all the other standard interactions available to desktop systems,[5] gestural interfaces can take advantage of the whole body for triggering system behaviors. The flick of a finger can start a scroll. The twist of a hand can transform an image. The sweep of an arm can clear a screen. A person entering a room can change the temperature.

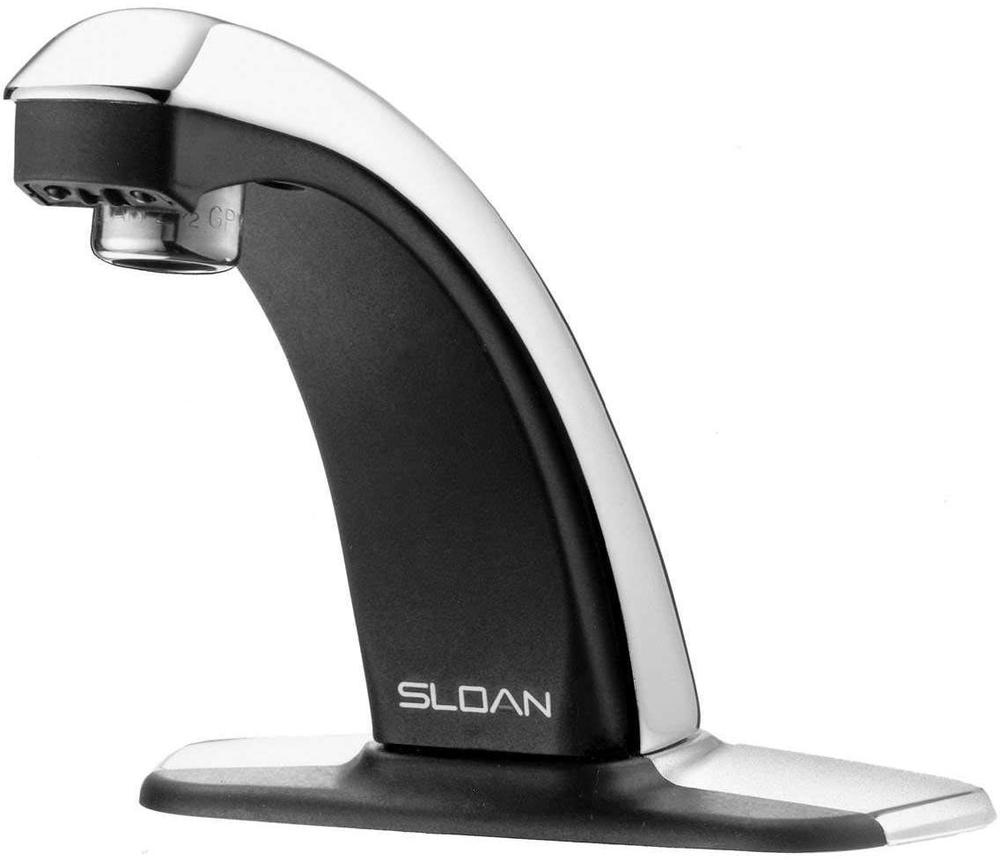

Figure 1-5. If you don't need a keyboard, mouse, or screen, you don't need much of an interface either. You activate this faucet by putting your hands beneath it. Of course, this can lead to confusion. If there are no visible controls, how do you know how to even turn the faucet on? Courtesy Sloan Valve Company.

Removing the constraints of the k-eyboard-controller-screen setup of most mobile devices and desktop/laptop computers allows devices employing interactive gestures to take many forms. Indeed, the form of a "device" can be a physical object that is usually analog/mechanical. Most touchscreens are like this, appearing as normal screens or even, in the case of the iPhone and iPod Touch, as slabs of black glass. And the "interface"? Sometimes all but invisible. Take, for instance, the motion-activated sinks now found in many public restrooms. The interface for them is typically a small sensor hidden below the faucet that, when detecting movement in the sink (e.g., someone putting her hands into the sink), triggers the system to turn the water on (or off).

Computer scientists and human-computer interaction advocates have been talking about this kind of "embodied interaction" for at least the past two decades. Paul Dourish in his book Where the Action Is captured the vision well:

"By embodiment, I don't mean simply physical reality, but rather, the way that physical and social phenomena unfold in real time and real space as a part of the world in which we are situated, right alongside and around us...Interacting in the world, participating in it and acting through it, in the absorbed and unreflective manner of normal experience."

As sensors and microprocessors have become faster, smaller, and cheaper, reality has started to catch up with the vision, although we still have quite a way to go.

Of course, it hasn't happened all at once. Samuel C. Hurst created the first touch device in 1971, dubbed the Elograph.[6] By 1974, Hurst and his new company, Elographics, had developed five-wire resistive technology, which is still one of the most popular touchscreen technologies used today. In 1977, Elographics, backed by Siemens, created Accutouch, the first true touchscreen device. Accutouch was basically a curved glass sensor that became increasingly refined over the next decade.

Myron Krueger created in the late 1970s what could rightly be called the first indirect manipulation interactive gesture system, dubbed VIDEOPLACE. VIDEOPLACE (which could be a wall or a desk) was a system of projectors, video cameras, and other hardware that enabled users to interact using a rich set of gestures without the use of special gloves, mice, or styli.

Figure 1-7. In VIDEOPLACE, users in separate rooms were able to interact with one another and with digital objects. Video cameras recorded users' movements, then analyzed and transferred them to silhouette representations projected on a wall or screen. The sense of presence was such that users actually jumped back when their silhouette touched that of other users. Courtesy Matthias Weiss.

In 1982, Nimish Mehta at the University of Toronto developed what could be the first multitouchsystem, the Flexible Machine Interface, for his master's thesis.[7] Multitouch systems allow users more than one contact point at a time, so you can use two hands to manipulate objects on-screen or touch two or more places on-screen simultaneously. The Flexible Machine Interface combined finger pressure with simple image processing to create some very basic picture drawing and other graphical manipulation.

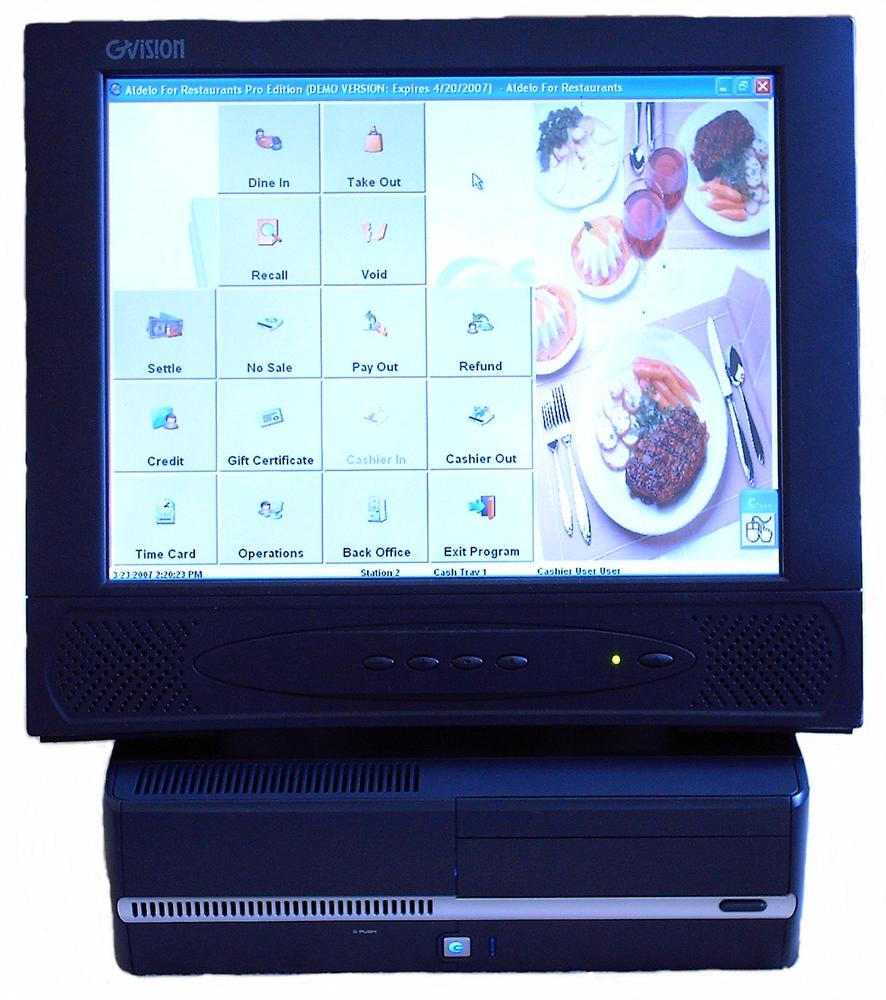

Outside academia, the 1980s found touchscreens making their way to the public first (as most new technology does) in commercial and industrial use, particularly in point-of-sale (POS) devices in restaurants, bars, and retail environments. Currently, touchscreen POS devices have penetrated more than 90% of food and beverage establishments in the United States.[8]

Figure 1-8. A POS touchscreen. According to the National Restaurant Association, touchscreen POS systems pay for themselves in savings to the establishment. Courtesy GVISION USA, Inc.

The Hewlett-Packard 150 was probably the first computer sold for personal use that incorporated touch. Users could touch the screen to position the cursor or select on-screen buttons, but the touch targets (see later in this chapter) were fairly primitive, allowing for only approximate positioning.

Figure 1-9. Released in 1983, the HP 150 didn't have a traditional touchscreen, but a monitor surrounded by a series of vertical and horizontal infrared light beams that crossed just in front of the screen, creating a grid. If a user's finger touched the screen and broke one of the lines, the system would position the cursor at (or more likely near) the desired location, or else activate a soft function key. Courtesy Hewlett-Packard.

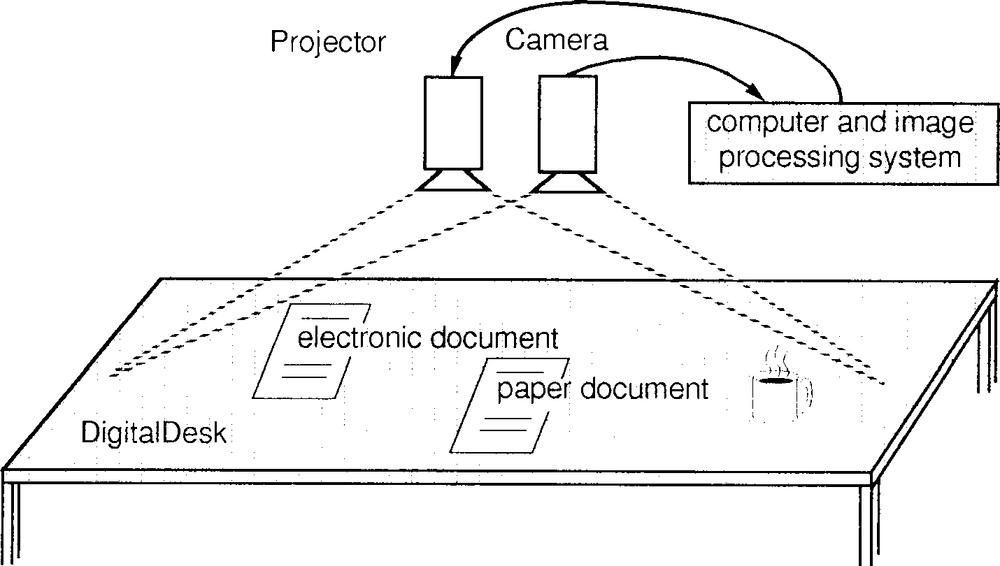

At Rank EuroPARC, Pierre Wellner designed the Digital Desk in the early 1990s.[9] The Digital Desk used video cameras and a projector to project a digital surface onto a physical desk, which users could then manipulate with their hands.[10] Notably, the Digital Desk was the first to use some of the emerging patterns of interactive gestures such as Pinch to Shrink (see Chapter 3).

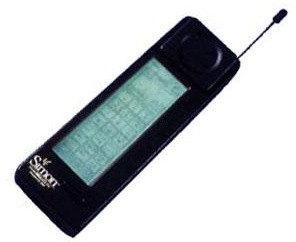

More than a decade before Apple released the iPhone (and other handset manufacturers such as LG, Sony Ericsson, and Nokia released similar touchscreen phones as well), IBM and Bell South launched Simon, a touchscreen mobile phone. It was ahead of its time and never caught on, but it demonstrated that a mobile touchscreen could be manufactured and sold.

Figure 1-11. Simon, released in 1994, was the first mobile touchscreen device. It suffered from some serious design flaws, such as not being able to show more than a few keyboard keys simultaneously, but it was a decade ahead of its time. Courtesy IBM.

In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, touchscreens began to make their way into wide public use via retail kiosks, public information displays, airport check-in services, transportation ticketing systems, and new ATMs.

Figure 1-12. Antenna Design's award-winning self-service check-in kiosk for JetBlue Airlines. Courtesy JetBlue and Antenna Design.

Lionhead Studios released what is likely the first home gaming gestural interface system in 2001 with its game, Black & White. A player controlled the game via a special glove that, as the player gestured physically, would be mimicked by a digital hand on-screen. In arcades in 2001, Konami's MoCap Boxing game had players put on boxing gloves and stand in a special area monitored with infrared motion detectors, then "box" opponents by making movements that actual boxers would make.

Figure 1-13. The Essential Reality P5 Glove is likely the first commercial controller for gestural interfaces, for use with the game Black & White. Courtesy Lionhead Studios.

The mid-2000s have simply seen the arrival of gestural interfaces for the mass market. In 2006, Nintendo released its Wii gaming system. In 2007, to much acclaim, Apple launched its iPhone and iPod Touch, which were the first touchscreen devices to receive widespread media attention and television advertising demonstrating their touchscreen capabilities. In 2008, handset manufacturers such as LG, Sony Ericsson, and Nokia released their own touchscreen mobile devices. Also in 2008, Microsoft launched MS Surface, a large, table-like touchscreen that is used in commercial spaces for gaming and retail display. And Jeff Han now manufactures his giant touchscreens for government agencies and large media companies such as CNN.

The future (see Chapter 8) should be interesting.

[5] This has some notable exceptions. See later in this chapter.

[6] See http://www.elotouch.com/AboutElo/History/ for a detailed history of the Elograph.

[7] Mehta, Nimish. "A Flexible Machine Interface." M.A.Sc. thesis, Department of Electrical Engineering, University of Toronto, 1982. Supervised by Professor K.C. Smith.

[8] According to The Professional Bar and Beverage Manager's Handbook, by Amanda Miron and Douglas Robert Brown (Atlantic Publishing Company).

[9] Wellner, Pierre. "The DigitalDesk Calculator: Tactile Manipulation on a Desktop Display." Proceedings of the Fourth Annual Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology (UIST): 27–33, 1991.

[10] Watch the video demonstration at http://video.google.com/videoplay?docid=5772530828816089246.

Get Designing Gestural Interfaces now with the O’Reilly learning platform.

O’Reilly members experience books, live events, courses curated by job role, and more from O’Reilly and nearly 200 top publishers.