What is design thinking?

Human-centered design and the challenges of complex problem-solving.

Fractal art. (source: Pixabay)

Fractal art. (source: Pixabay)

What is it that we’re talking about, when we’re talking about design? We may first encounter design as aesthetic treatment and styling—certainly important, but not, of course, the entire story. Stylistic design is often seen in contrast with design as a process for tackling tough problems.

Design thinking is an abductive approach to complex problem solving that leverages the designer’s empathetic mindset in order to understand people’s unarticulated needs and identify opportunities for solutions. This is a human-centered innovation process that can be applied to a wide range of challenges: design thinking can be used to create everything from products and services to business models and processes.

Design thinking has a rich 30+ year history, underpinned by academic work at Stanford University’s design school and spearheaded in the business world by design firm IDEO. In his 2009 book on design thinking, Change by Design, IDEO CEO Tim Brown outlines it this way: “Design is about delivering a satisfying experience. Design thinking is about creating a multipolar experience in which everyone has the opportunity to participate in the conversation.” Jordan Shade, a global facilitation lead and design researcher at IBM, describes the cooperation and cross-pollination inherent in design thinking as “having radical collaboration with a really diverse group of people who can think divergently, and not just jump into the first idea that comes along their way.”

Design thinking and business thinking are not opposites or poles, but they do provide different perspectives and ways of problem solving. While business thinking methods may rely upon inductive approaches—with an emphasis on financial optimization or technical prowess—design thinking, in contrast, emphasizes a humanistic and holistic view that integrates people’s needs into the mix, working with oftentimes incomplete information, to imagine what could be. “I see them as being, if not highly overlapping, very complimentary in most cases,” says Shade. “Design thinking has a very natural tendency to be impactful to business.”

“It’s not as simple as [just] identifying a problem. ‘Yay! We found something that customers are frustrated with. That’s a business opportunity!’” says Travis Lowdermilk, a senior UX designer at Microsoft. “It’s also responding to that problem in a way that customers feel like A) it not only solves [it], but B) it solves it in a way that customers find valuable.”

As our rapidly evolving creative economy has increasingly shifted value to industries and jobs focused on knowledge work—such as science and technology—design thinking has increased in importance. The 21st century marketplace is characterized by digital disruption and change brought on by emerging technologies. Traditional business thinking methods can overemphasize analysis and deliberation, making it difficult for organizations to react quickly. In contrast, design thinking emphasizes learning by doing and agile, iterative solutions that can have startlingly effective results.

Companies as varied as Apple, Cisco, GE, IBM, Intuit, Kaiser Permanente, Microsoft, Nike, and Samsung have used design thinking to innovate their products and services. For example, GE’s health care division used design thinking to better understand the needs of customers for its MRI machines, which resulted in an improved experience for children and families.

Doug Dietz, a designer at GE, realized that their machines were not providing a positive patient experience when he witnessed the tearful reaction of a young girl as she and her family approached the MRI scan room. The girl was so terrified, in fact, that she required anesthesia to undergo the MRI. Dietz took an empathetic, human-centered design approach to solving this patient experience challenge, eventually prototyping a series of kid-friendly adventures that used the MRI scanner as a prop in a story, decked out with various decals and decorations. The stories about pirate ships and space ships also integrated the MRI technician, who facilitated the scripted adventure. What were the results of this imaginative solution? Delighted kids and families, and improved experience at hospitals as fewer children required sedation to undergo an MRI.

As we can see from this example, design thinking can help organizations identify opportunities, unlock innovation, and improve their businesses. While the name and number of its key principles may vary depending on which design thinking model we subscribe to, its basic elements always include some flavor of these: research / problem definition, ideation, and prototyping / testing.

Researching and defining

Design thinking draws upon user-centered research techniques, including ethnographic analysis, for understanding customers and users. During the first phase of the design thinking process, our goal is to understand and empathize with the people for whom we’re designing. We can do this by observing and interviewing people—immersing ourselves into the context of use to better understand the user journey, pain points, and unmet needs. This information will become inspiration for the next steps in the process.

Bill Hartman, the innovation strategy partner at Boston-based firm Essential Design, believes design teams are empowered and inspired through field research and contextual inquiry. “When we do design research programs here at Essential, we always try to bring a member of the client’s project team with us in the field. So, as we are developing empathy for end users, they too have empathy for what we’re seeing, what we’re hearing, what we’re learning. And, they can be advocates for that first-hand understanding of challenges and goals with their teams over the long haul.”

Field research provides the basis for Essential’s design thinking process, enabling the team to gain insight into the user’s world. “I think that storytelling and doing things like ethnographic studies, that not only find facts but also create opportunities to ask smarter questions, is really the necessary fodder,” Hartman explains.

So, how should we approach field research?

Observing

We want to know why people do what they do, and how they do it. Time spent observing people in context, seeing them in their everyday routines and typical environment, is invaluable for discovering unknown behaviors, uncovering unmet needs, and identifying future opportunities.

Interviewing

We will also converse with people and listen to their stories as we seek to uncover what is meaningful to them. We need to fully understand their needs and goals—what they feel, value, and believe.

Problem Finding

After conducting design research, we’ll try to make sense of the inputs and synthesize the information we’ve gathered. In doing so, we may discover valuable insights into user behavior and identify real opportunities. What patterns are emerging from the data? What is bubbling to the top? We want to address the right challenge that is most meaningful to our audience.

Travis Lowdermilk describes how his team brought a new perspective to sense-making for design research at Microsoft. “We looked at the way intelligence officials analyzed all the data signals that they’re getting. … In that business, it’s all about finding the thing that’s sitting right in front of you, that everybody’s overlooking. It [has some parallels] to trying to identify customer problems and looking for business opportunities. Sometimes those things are staring right in your face. You just don’t see it because you don’t have a sense of awareness or mindfulness about what’s happening around you.”

Finding the right problems to solve is an increasingly important part of design. “The first thing that comes to my mind around what’s needed in the design community, especially around technology, is more wisdom. I say this because I think we are good—we often talk about making the right thing and making the thing right—and I think we’re pretty good at that, to a certain scale or a certain scope. At the same time, I think we need to be thinking bigger and probably more systemically,” said Kristian Simsarian, chair of the Interaction Design Program at the California College of the Arts in an interview on the O’Reilly Design podcast.

Ideating

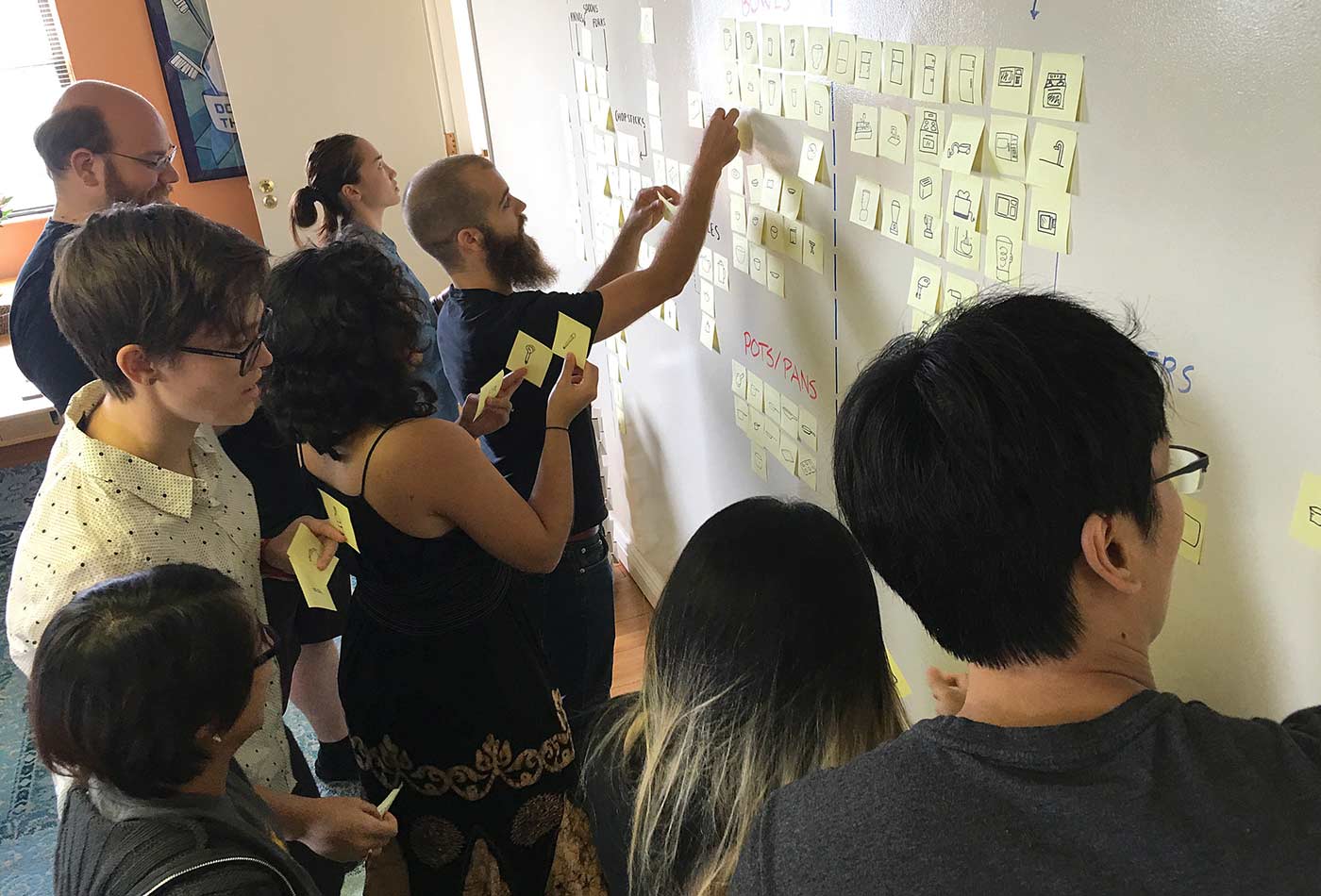

During the ideation phase of the design thinking process, our goal is to generate a large number of interesting ideas representing potential solutions. Our ideation techniques might include sketching, brainstorming, and mind mapping to create high-level concepts. At this point, we’ll want to describe a wide variety of design approaches; it’s important that we don’t get attached to any one idea in particular. As designers, we shouldn’t worry about being “right,” but rather go for a broad array. We’ll then select a few of the best with which to move forward.

“That’s really what any innovation team is trying to accomplish: something that’s new to the world, that doesn’t yet exist, that is going to be better differentiated and competitive in the marketplace,” says Hartman.

Prototyping and iterating

Making ideas tangible is critical to the design thinking process, as are the iteration cycles needed for testing and refining those ideas. Design has a bias toward making things, and prototyping is where it all begins. To properly evaluate a design concept, we need to prototype it in the same environment and context in which it will eventually function.

Based on the best concepts from our ideation exercises, we’ll create prototypes for demonstrating and validating the basic designs. Prototypes can be low or high fidelity, be interactive or static, but regardless they should convey the basic experience flow. We cannot evaluate design ideas properly without a prototype that approximately conveys the function. For applications, this might mean creating with code to test and evaluate a working prototype. For services, this could mean creating scripted walkthroughs that approximate the human-to-human interactions. Through the process of prototyping, learning from testing usage in the real world by real people, and iterating based on that learning, we progress toward a solution.

“A prototype doesn’t need to be a working prototype at all,” says Hartman. “It can simply prototype the experience of using this product or system in a way that helps people understand what this use case could be like. Does it seem believable? Is it appealing? What would I change about it ideally before the investment is made in creating any working prototype? I always call it ‘prototyping experience before prototyping the prototype’. That [technique] has given us very good guidance in a relatively quick time frame and at a fairly small development cost.”

While design thinking models don’t necessarily include an implementation phase, it’s always worthy of consideration. Once we evaluate our prototypes and choose a direction, we should also identify how to bring our new solution to life. We’ll need to prioritize, making the hard choices regarding potential trade-offs.

Measuring return on investment

There are a variety of potential measures for calculating the return on investment (ROI) for design thinking. While every company and product is different, useful metrics include cultural measures, such as employee satisfaction, internal engagement, and efficiency; financial measures, like sales and productivity; and product quality measures, such as customer satisfaction.

Design thinking can enable better decision-making around the creation of products and services. “What doesn’t often get appreciated about design thinking on the research and analytical side of things, is how often we put ideas to bed very quickly, or pivot as a result of funneling our understanding of customers in our creative and ideative process,” says Lowdermilk. “You forget the moments that you said, ‘Boy, this isn’t the right direction.’ … We forget that fork in the road and when that moment happened. But had it not happened, [it can be] incredibly costly to an organization to go in the wrong direction. … You don’t appreciate those things until you got it wrong and you’ve invested a [lot] of money into building something and marketing dollars and positioning and strategy, and nobody shows up.”

Ultimately, design thinking and business thinking must work together. “Our client teams measure success in relatively different ways, but it typically ties back to the business goals themselves,” says Hartman. “One that comes to mind is some work we [did] with an electronics manufacturer who simply wanted to reduce the call volume coming into their support centers. They noticed people struggling with the out-of-the-box experience and the setup of some appliances and electrical devices. [The company] had already off-shored many of their call centers to try to keep these costs in check. But if through more intuitive product design, better design of the collateral that comes with those products, we could mitigate those calls in the first place, then we [could] really create a business win. Money saved is money earned.”

Where is design thinking taking us?

In this dynamic 21st century economy, companies are increasingly recognizing the value of incorporating design thinking into their products, services, and business practices. On an organizational level, design thinking can help companies shift their offerings and even their culture. “Microsoft is one of those [companies],” says Lowdermilk. “We’re trying to use [design thinking] principles to better collaborate internally and bring our internal organization together, so we can bring our product families closer together and create these really delightful experiences.”

How do we adopt design thinking into our organizations? And how do we measure that adoption? At IBM, Jordan Shade is thinking about awareness and educational efforts, as well as understanding if teams are applying design thinking tools, methods, and mindsets in their work. That requires understanding the maturity path of the team as they adopt design thinking. “One of my favorite hard metrics to look at is: can you show me a released piece of software, or service, depending on your space, that’s in the wild, and point out places where you made decisions based on user research? That’s something so tangible that, as a researcher myself, I know that it is the holy grail.”

At Intuit, Suzanne Pellican, vice president of experience design, describes the eight-year journey to becoming a design-focused company in Design thinking in the corporate DNA: “… because we invested in building innovation skills into our employee base, we are not only a design-thinking company—we’re a design-driven company. Meaning, we’re going from creating a culture of design thinking to building a practice of design doing, where we relentlessly focus on nailing the end-to-end customer experience. This means that before anything gets built, the whole team—engineers, designers, marketers, product managers—are interfacing with the customers to ensure they understand the problem well, and together, they design the best solution.”

Design thinking is helping organizations change their cultures to become more customer-centric and collaborative. While this type of deep culture shift doesn’t happen overnight, it can ultimately propel organizations forward to serve new markets and redefine businesses. For designers, this is a golden opportunity: “We need the way you think. We need the way you process ideation. We need your style of work that’s agile and iterative. We need your creativity,” says Lowdermilk. And that’s where it all begins.

Resources

Ready to take a deeper dive into design thinking? Check out these resources:

- Stanford University Institute of Design (d.school) — Use Our Methods

- Change by Design, by Tim Brown

- Design Kit, by IDEO.org

- Design Thinking for Strategic Innovation: What They Can’t Teach You at Business or Design School, by Idris Mootee

- Building a design driven culture, by Jennifer Kilian, Hugo Sarrazin, and Hyo Yeon