Tweets loud and quiet

Twitter’s long, long, long tail suggests the service is less democratic than it seems.

Writers who cover Twitter find the grandiose irresistible: nearly every article about the service’s IPO this fall mentioned the heroes of the Arab Spring who toppled dictators with 140-character stabs, or the size of Lady Gaga’s readership, which is larger than the population of Argentina.

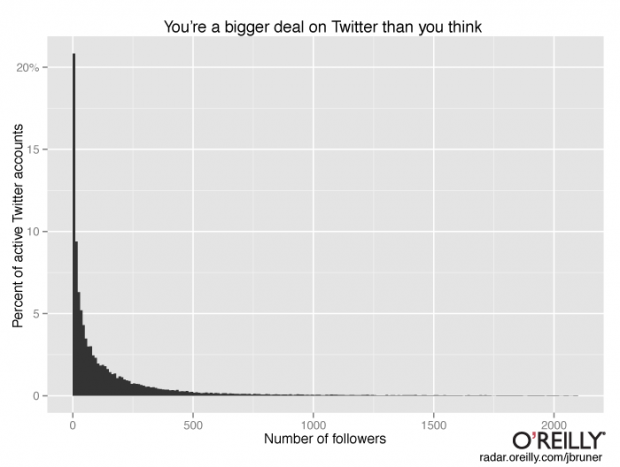

But the bulk of the service is decidedly smaller-scale–a low murmur with an occasional celebrity shouting on top of it. In comparative terms, almost nobody on Twitter is somebody: the median Twitter account has a single follower. Among the much smaller subset of accounts that have posted in the last 30 days, the median account has just 61 followers. If you’ve got a thousand followers, you’re at the 96th percentile of active Twitter users. (I write “active users” to refer to publicly-viewable accounts that have posted at least once in the last 30 days; Twitter uses a more generous definition of that term, including anyone who has logged into the service.)

This is a histogram of Twitter accounts by number of followers. Only accounts that have posted in the last 30 days are included.

For a few weeks this fall I had my computer probe the Twitterverse, gathering details on a random sampling of about 400,000 Twitter accounts. The profile that emerges suggests that Twitter is more a consumption medium than a conversational one–an only-somewhat-democratized successor to broadcast television, in which a handful of people wield enormous influence and everyone else chatters with a few friends on living-room couches. There are undoubtedly some influential Twitter users who would not be influential without Twitter, but I suspect that most people who have, say, 3,000 followers (the top one percent) were prominent commentators, industry experts, or gregarious accumulators of friends to begin with.

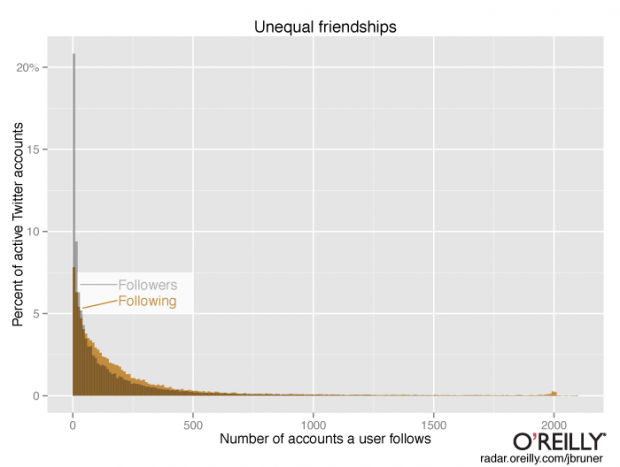

Active Twitter accounts follow a median 117 users, and the vast majority of them–76%–follow more people than follow them. Which brings to mind both discussions about the mathematics of pairing and studies that suggest reciprocated friendship is both rare and valuable. Here’s the histogram from above with the distribution of number of accounts that users follow superimposed.

Not that number of followers is an indicator of quality. Twitter’s users are prone to swarms and fads; they flock to famous people as soon as they appear on Twitter, irrespective of both activity and brow height. Former New York Times editor Bill Keller amassed thousands of followers in his first months on Twitter, despite posting just eight times in 2009 (and then baffling his readers with this tweet upon reappearing on Christmas Eve in 2010). On the other end, just under one in every thousand Twitter accounts has a name that refers to Justin Bieber in some way; an additional one in every thousand refers to Bieber in its account description.

Far more inscrutable than the famous zombies are the anonymous ones, like a Wayne Rooney fan account, a skin-care promotion feed, and a fake Taylor Lautner account that each managed to amass thousands of followers with just a single tweet. (The commercial accounts of this sort are probably the result of promotions–“follow us on Twitter for a discount!”–that got no follow-up, or are the beneficiaries of bot armies hired to make a business look popular.)

Twitter is giant, and it has an outsize influence on popular and not-so-popular culture, but that influence seems due to the fact that it’s popular among influential people and provides energetic reverberation for their thoughts–and lots and lots of people who sit back and listen.

How you stack up

| Percentile of active Twitter accounts | Number of follwers |

| 10 | 3 |

| 20 | 9 |

| 30 | 19 |

| 40 | 36 |

| 50 | 61 |

| 60 | 98 |

| 70 | 154 |

| 80 | 246 |

| 90 | 458 |

| 95 | 819 |

| 96 | 978 |

| 97 | 1,211 |

| 98 | 1,675 |

| 99 | 2,991 |

| 99.9 | 24,964 |

The technical mumbo-jumbo

Twitter assigns each account a numerical ID on creation. These IDs aren’t consecutive, but they do, with just a few exceptions, monotonically increase over time–that is, a newer account will always have a higher ID number than an older account. In mid-September, new accounts were being assigned IDs just under 1.9 billion.

Every few minutes, a Python script that I wrote generated a fresh list of 300 random numbers between zero and 1.9 billion and asked Twitter’s API to return basic information for the corresponding accounts. I logged the results–including empty results when an ID number didn’t correspond to any account–in a MySQL table and let the script run on a cronjob for 32 days. I’ve only included accounts created before September 2013 in my analysis in order to avoid under-sampling accounts that were created during the period of data collection.

Twitter IDs are assigned at an overall density of about 63%–that is, given an integer between zero and the highest number so far assigned, there’s a 63% chance that a Twitter account has been opened with that number at some point. That density isn’t constant over the whole range of ID numbers, though; Twitter appears to have changed its ID-assignment scheme around July 2012. Before then, Twitter assigned IDs at a density of about 86% and afterward at 49%.

With a large survey sample of Twitter accounts, I was able to project the size and characteristics of the Twitter ecosystem as a whole, using R and ggplot2 for my analysis.

This post was modified after publication in order to add the table of follower percentiles above.