RxJava for Android app development

RxJava is a powerful library, but it has a steep learning curve. Learn RxJava by seeing how it can make asynchronous data handling in Android apps much cleaner and more flexible.

Streams (source: © Alexassault | Dreamstime.com )

Streams (source: © Alexassault | Dreamstime.com )

An Introduction to RxJava

Observables

RxJava’s asynchronous data streams are “emitted” by Observables. The reactive extensions website calls Observables the “asynchronous/push ‘dual’ to the synchronous/pull Iterable.” Although Java’s Iterable is not a perfect dual of RxJava’s Observables, reminding ourselves how Java’s Iterables work can be a helpful way of introducing Observables and asynchronous data streams.

Every time we use the for-each syntax to iterate over a Collection, we are taking advantage of Iterables. If we were building our HackerNews client, we might loop over a list of Storys and log the titles of those Storys:

for (Story story : stories) {

Log.i(TAG, story.getTitle());

}

This is equivalent to the following:2

for (Iterator<Story> iterator = stories.iterator(); iterator.hasNext();) {

Story story = iterator.next();

Log.i(TAG, story.getTitle());

}

As we can see in the preceding code, Iterables expose an Iterator that can be used to access the elements of a Collection and to determine when there are no more unaccessed elements left in the Collection.3 Any object that implements the Iterable interface is, from the perspective of clients interacting with that interface, an object that provides access to a stream of data with a well-defined termination point.

Observables are exactly like Iterables in this respect: they provide objects access to a stream of data with a well-defined termination point.

The key difference between Observables and Iterators is that Observables provide access to asynchronous data streams while Iterables provide access to synchronous ones. Accessing a piece of data from an Iterable‘s Iterator blocks the thread until that element has been returned. Objects that want to consume an Observable‘s data, on the other hand, register with that Observable to receive that data when it is ready.

Note

The Key Difference between Observables and Iterables

Observables provide access to asynchronous data streams while Iterables provide access to synchronous ones.

To make this distinction more concrete, think again about the preceding snippet that logs a HackerNews story’s title within a Collection<Story>. Now imagine that the Storys logged in that snippet were not available in memory, that each story had to be fetched from the network, and that we wanted to log the Storys on the main thread. In this case, we would need the stream of Storys to be an asynchronous stream and using an Iterable to access each element in that stream would be inappropriate.

Instead, in this case, we should use an Observable to access each story as it is returned by the HackerNews API. Now, we know that we can access an element in an Iterable‘s stream of data by calling Iterator.next() on its Iterator. We do not know, however, how to access the elements of an Observable‘s asynchronous data stream. This brings us to the second fundamental concept in RxJava: the Observer.

Observers

Observers are consumers of an Observable‘s asynchronous data stream. Observers can react to the data emitted by the Observable in whatever way they want. For example, here is an Observer that logs the titles of Storys emitted by an Observable:

storiesObservable.subscribe(new Observer<Story>() {

@Override

public void onCompleted() {}

@Override

public void onNext(Story story) {

Log.i(TAG, story.getTitle());

}

//...

});

Note that this code is very similar to the previous for-each snippet. In both snippets, we are consuming a data stream with a well-defined termination point. When we loop through a Collection using the for-each syntax, the loop terminates when iterator.hasNext() returns false. Similarly, in the preceding code, the Observer knows that there are no more elements left in the asynchronous data stream when onCompleted() is called.

The main difference between these two snippets is that when we loop over a Collection, we’re logging the Story titles synchronously and we when subscribe to the stringsObservable, we’re registering to log the Story titles asynchronously as they become available.

An Observer can also handle any exceptions that may occur while the Observable is emitting its data. Observers handle these errors in their onError() method.

To see why this is a useful feature of RxJava, imagine for a moment that the Story objects emitted by the Observable are objects that are converted from a JSON response to a HackerNews API call. If the HackerNews API returned malformed JSON, which in turn caused an exception in converting the JSON to Story model objects, the Observer would receive a call to onError(), with the exception that was thrown when the malformed JSON was being parsed.

At this point, there are two pieces of the aforementioned definition of RxJava that should be clearer. To see this, let’s take a second look at that definition:

RxJava is a library that allows us to represent any operation as an asynchronous data stream that can be created on any thread, declaratively composed, and consumed by multiple objects on any thread.

We have just seen that Observables are what allow us to represent any operation as an asynchronous data stream. Observables are similar to Iterables in that they both provide access to data streams with well-defined termination points. We also now know an important difference between Observables and Iterables: Observables expose asynchronous data streams while Iterables expose synchronous ones.

Observers are objects that can consume the asynchronous data emitted by an Observable. There can be multiple Observers that are registered to receive the data emitted by an Observable. Observers can handle any errors that might occur while the Observable is emitting its data and Observers know when there are no more items that will be emitted by an Observable.

There are still some things from the preceding definition of RxJava that are unclear. How exactly does RxJava allow us to represent any operation as an asynchronous data stream? In other words, how do Observables emit the items that make up their asynchronous data streams? Where do those items come from? These are questions that we will address in the next section.

Observable Creation and Subscribers

Observables emit asynchronous data streams. The way in which Observables emit their items again has some similarities to how Iterables expose their data streams. To see this, recall that Iterables and Iterators are both pieces of the Iterator pattern, a pattern whose main aim is well captured by the Gang of Four in Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software:

Provide a way to access the elements of an aggregate object without exposing its underlying representation.4

The Iterator pattern allows any object to provide access to its elements without exposing that object’s underlying representation. Similarly, Observables provide access to the elements of an asynchronous data stream in a way that completely hides and is largely independent of the process by which that data stream is created. This allows Observables to represent virtually any operation.

Here is an example that will make the Observable‘s flexibility more concrete. Observables are typically created by passing in a function object that fetches the items of an asynchronous data stream and notifies a Subscriber that those items have become available. A Subscriber is just an Observer that can, among other things, unsubscribe itself from the items emitted by an Observable.

Here is how you would create an Observable that emits some HackerNews Storys that have been fetched from the API:

Observable.create(new Observable.OnSubscribe<Story>() { //1

@Override

public void call(Subscriber<? super Story> subscriber) {

if (!subscriber.isUnsubscribed()) { //2

try {

Story topStory = hackerNewsRestAdapter.getTopStory(); //3

subscriber.onNext(topStory); //4

Story newestStory = hackerNewsRestAdapter.getNewestStory();

subscriber.onNext(newestStory);

subscriber.onCompleted(); //5

} catch (JsonParseException e) {

subscriber.onError(e); //6

}

}

}

});

Let’s run through what’s happening here step by step:

- The name “OnSubscribe” provides us with a clue about when this code is typically executed: when an

Observeris registered to receive the items emitted by thisObservablethrough a call toObservable.subscribe(). - We check to see if the

Subscriberis unsubscribed before emitting any items. Remember: aSubscriberis just anObserverthat can unsubscribe from theObservablethat emits items. - We are actually fetching the HackerNews data with this method call. Notice that this is a synchronous method call. The thread will block until the

Storyhas been returned. - Here we are notifying the

Observerthat has subscribed to theObservablethat there is a newStoryavailable. TheObserverhas been wrapped by theSubscriberpassed into thecall()method. TheSubscriberwrapper, in this case, simply forwards its calls to the wrappedObserver. - When there are no more

Storys left to emit in thisObservable‘s stream, we notify theObserverwith a call toonCompleted(). - If there’s an error parsing the JSON response returned by the HackerNews API, we notify the

Observerwith a call toonError().

Warning

Creating Observables Inside Activitys Can Cause Memory Leaks

For reasons that we will point out in the next chapter, you should be careful when calling Observable.create() within an Activity. The preceding code snippet we just reviewed would actually cause a memory leak if it was called within an Activity.

As you can see from the preceding snippet, Observables can be created from pretty much any operation. The flexibility with which Observables can be created is another way in which they are like Iterables. Any object can be made to implement the Iterable interface, thereby exposing a stream of synchronous data. Similarly, an Observable‘s data stream can be created out of the work done by any object, as long as that object is passed into the Observable.OnSubscribe that’s used to create an Observable.

At this point, astute readers might wonder whether Observables really do emit streams of asynchronous data. Thinking about the previous example, they might wonder to themselves, “If the call() method on the Observable.OnSubscribe function object is typically called when Observable.subscribe() is invoked and if that method invokes blocking synchronous methods on the hackerNewsRestAdapter, then wouldn’t calling Observable.subscribe() block the main thread until the Observable has finished emitting the Storys returned by the hackerNewsRestAdapter?”

This is a great question. Observable.subscribe() would actually block the main thread in this case. There is, however, another piece of RxJava that can prevent this from happening: a Scheduler.

Schedulers

Schedulers determine the thread on which Observables emit their asynchronous data streams and the thread on which Observers consume those data streams. Applying the correct Scheduler to the Observable that is created in the preceding snippet will prevent the code that runs in the call() method of Observable.OnSubscribe from running on the main thread:

Observable.create(new Observable.OnSubscribe<Story>() {

//...

}).subscribeOn(Schedulers.io());

As the name implies, Schedulers.io() returns a Scheduler that schedules the code that runs in the Observable.OnSubscribe object to be run on an I/O thread.

There is another method on Observable that takes a Scheduler: observeOn(). The Scheduler passed into this method will determine the thread on which the Observer consumes the data emitted by the Observable subscribeOn() actually returns an Observable, so you can chain observeOn() onto the Observable that is returned by the call to subscribeOn():

Observable.create(new Observable.OnSubscribe<Story>() {

//...

})

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread());

AndroidSchedulers.mainThread() does not actually belong to the RxJava library, but that is beside the point here.5 The main point is that by calling observeOn() with a specific Scheduler, you can modify the thread on which Observers consume the data emitted by the Observable.

The subscribeOn() and observeOn() methods are really instances of a more general way in which you can modify the stream emitted by an Observable: operators. We will talk about operators in the next section. For now, let’s return to the definition of RxJava with which we opened to briefly take stock of what we have just learned:

RxJava is a library that allows us to represent any operation as an asynchronous data stream that can be created on any thread, declaratively composed, and consumed by multiple objects on any thread.

What we have just covered in this section is how RxJava allows us to create and consume asynchronous data streams on any thread. The only piece of this definition that should be unclear at this point is the phrase “declaratively composed.” This phrase, as it turns out, is directly related to operators.

Operators

The Schedulers we discussed in the previous section were passed into both the Observable.subscribeOn() and Observable.observeOn() methods. Both of these methods are operators. Operators allow us to declaratively compose Observables. In order to get a better grip on operators, let’s briefly break down the phrase “declaratively compose.”

To compose an Observable is simply to “make” a complex Observable out of simpler ones. Observable composition with operators is very similar to the composition that occurs in function composition, the building of complex functions out of simpler ones. In function composition, complex functions are built by taking the output of one function and using it as the input of another function.

For example, consider the Math.ceil(int x) function. It simply returns the next integer closest to negative infinity that’s greater than or equal to x . For example, Math.ceil(1.2) returns 2.0. Now, suppose we had takeTwentyPercent(double x), a function that simply returned 20% of the value passed into it. If we wanted to write a function that calculated a generous tip, we could compose Math.ceil() and takeTwentyPercent() to define this function:

double calculateGenerousTip(double bill) {

return takeTwentyPercent(Math.ceil(bill));

}

The complex function calculateGenerousTip() is composed from the result of passing the output of Math.ceil(bill) as the input of takeTwentyPercent().

Operators allow us to compose Observables in a way that is similar to the way in which calculateGenerousTip() is composed. An operator is applied to a “source” Observable and it returns a new Observable as a result of its application. For example, in the following snippet, the source Observable would be storiesObservable:

Observable<String> ioStoriesObservable = storiesObservable. .subscribeOn(Schedulers.io());

ioStoriesObservable, of course, is the Observable that’s returned as a result of applying the subcribeOn operator. After the operator is applied, the returned Observable is more complex: it behaves differently from the source Observable in that it emits its data on an I/O thread.

We can take the Observable returned by the subscribeOn operator and apply another operator to further compose the final Observable whose data we will subscribe to. This is what we did earlier when we chained two operator method calls together to ensure that the asynchronous stream of Story titles was emitted on a background thread and consumed on the main thread:

Observable<String> androidFriendlyStoriesObservable = storiesObservable

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread());

Here we can see that the composition of the Observable is just like the composition of a function. calculateGenerousTip() was composed by passing the output of Math.ceil() to the input of takeTwentyPercent(). Similarly, androidFriendlyStoriesObservable is composed by passing the output of applying the subcribeOn operator as the input for applying the observeOn operator.

Note that the way in which operators allow us to compose Observables is declarative. When we use an operator, we simply specify what we want our composed Observable to do instead of providing an implementation of the behavior we want out of our composed Observable. When we apply the observeOn and subscribeOn operators, for example, we are not forced to work with Threads, Executors, or Handlers. Instead, we can simply pass a Scheduler into these operators and this Scheduler is responsible for ensuring that our composed Observable behaves the way we want it to. In this way, RxJava allows us to avoid intricate and error-prone transformations of asynchronous data.

Composing an “android friendly” Observable that emits its items on a background thread and delivers those items to Observers on the main thread is just the beginning of what you can accomplish with operators. Looking at how operators are used in the context of an example can be an effective way of learning how an operator works and how it can be useful in your projects. This is something we will do in detail in the next chapter.

For now, let’s simply introduce one additional operator and work it into our HackerNews stories example code.The map operator creates a new Observable that emits items that have been converted from items emitted by the source Observable. The map operator would allow us, for example, to turn an Observable that emits Storys into an Observable that emits the titles of those Storys. Here’s what that would look like:

Observable.create(new Observable.OnSubscribe<Story>() {

//Emitting story objects...

})

.map(new Func1<Story, String>() {

@Override

public String call(Story story) {

return story.getTitle();

}

});

The map operator will return a new Observable<String> that emits the titles of the Story objects emitted by the Observable returned by Observable.create().

At this point, we know enough about RxJava to get a glimpse into how it allows us to handle asynchronous data neatly and declaratively. Because of the power of operators, we can start with an Observable that emits HackerNews Storys that are created and consumed on the UI thread, apply a series of operators, and wind up with an Observable that emits HackerNews Storys on an I/O thread but delivers the titles of those stories to Observers on the UI thread.

Here’s what that would look like:

Observable.create(new Observable.OnSubscribe<Story>() {

//Emitting story objects...

})

.map(new Func1<Story, String>() {

@Override

public String call(Story story) {

return story.getTitle();

}

})

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread());

Conclusion

At the beginning of this chapter, I gave a general definition of RxJava:

RxJava is a library that allows us to represent any operation as an asynchronous data stream that can be created on any thread, declaratively composed, and consumed by multiple objects on any thread.

At this point you should have a good grasp of this definition and you should be able to map pieces of the definition onto certain concepts/objects within the RxJava library. RxJava lets us represent any operation as an asynchronous data stream by allowing us to create Observables with an Observable.OnSubscribe function object that fetches data and notifies any registered Observers of new elements in a data stream, errors, or the completion of the data stream by calling onNext(), onError(), and onCompleted(), respectively. RxJava Schedulers allow us to change the threads on which the asynchronous data streams emitted by Observables are created and consumed. These Schedulers are applied to Observables through the use of operators, which allows us to declaratively compose complex Observables from simpler ones.

1Fragmented podcast, Episode 3, “The RxJava Show,” 32:26-32:50.

2See the Oracle docs.

3By the way, my usage of the for-each syntax should not be taken as a blanket endorsement for using for-each syntax while writing Android apps. Google explicitly warns us that there are cases where this is inappropriate.

4Design Patterns: Elements of Reusable Object-Oriented Software (Kindle edition)

5As I point out in the concluding section of this report, this method belongs to a library called “RxAndroid.”

6See the Project Kotlin Google doc.

RxJava in Your Android Code

We haven’t used Otto [an Android-focused event bus library] in a year and a half, if not more…We think we found a better mechanism. That mechanism is…RxJava where we can create a much more specific pipeline of events than a giant generic bus that just shoves any event across it.

Jake Wharton7

RxJava is a powerful library. There are many situations where RxJava provides a cleaner, more flexible way of implementing a feature within our Android apps. In this chapter, I try to show why you should consider using RxJava in your Android code.

First, I show that RxJava can load asynchronous data in a way that is both efficient and safe, even in cases where the data is loaded into objects whose lifecycle we do not control (e.g., Activitys, Fragments, etc.). Second, I compare an RxJava-based implementation of a search feature for our example HackerNews client app to a solution based on AsyncTasks, Handlers, and Listeners and I try to say a little about the advantages of the RxJava-based solution.

RxJava and the Activity Lifecycle

We do not have complete control over the lifecycle of the Activitys within our apps. Ultimately, the Android framework is responsible for creating and destroying Activitys. If the user rotates a device, for example, the Activity that is currently on screen may be destroyed and re-created to load the layout appropriate for the device’s new orientation.

This feature of the Android framework requires any effective asynchronous data loading solution to have two properties. First, it must be able to notify an Activity that its data-loading operation is complete without causing that Activity to leak. Second, it should not force developers to re-query a data source just because of a configuration change. Rather, it should hold onto and deliver the results of a data-loading operation to an Activity that’s been re-created after a configuration change. In this section, I show that if RxJava is used correctly, it can have these two properties and thus, that it can be an effective data-loading solution for Android apps.

Avoiding Memory Leaks

To avoid leaking an Activity within an Android app, we must ensure that any object that notifies an Activity when an asynchronous data load operation is complete does not a) live longer than the Activity and b) hold a strong reference to the Activity it seeks to notify. If both of these conditions are true, then the data-loading object will cause the Activity to leak. Memory leaks on resource-constrained mobile devices are especially problematic and can easily lead to the dreaded OOM errors that crash Android apps.

When we use RxJava for Android, we typically avoid causing memory leaks by ensuring that the Observables that emit asynchronous data do not hold a strong reference to an Activity after that Activity‘s onDestroy() method has been called. RxJava has several features that help us do this.

Any call to Observable.subscribe() returns a Subscription. Subscriptions represent a connection between an Observable that’s emitting data and an Observer that’s consuming that data. More specifically, the Subscription returned by Observable.subscribe() represents the connection between the Observable receiving the subscribe() message and the Observer that is passed in as a parameter to the subscribe() method. Subscriptions give us the ability to sever that connection by calling Subscription.unsubscribe().

In cases where an Observable may live longer than its Observer because it is emitting items on a separate thread calling Subscription.unsubscribe() clears the Observable‘s reference to the Observer whose connection is represented by the Subscription object. Thus, when that Observer is an Activity or an anonymous inner class that has an implicit reference to its enclosing Activity, calling unsubscribe() in an Activity‘s onDestroy() method will prevent any leaks from occurring. Typically this looks something like this:

@Override

public void onCreate() {

//...

mSubscription = hackerNewsStoriesObservable.subscribe(new Observer() {

@Override

public void onNext(Story story) {

Log.d(TAG, story);

}

});

}

@Override

public void onDestroy() {

mSubscription.unsubscribe();

}

If an Activity utilizes multiple Observables, then the Subscriptions returned from each call to Observable.subscribe() can all be added to a CompositeSubscription, a Subscription whose unsubscribe() method will unsubscribe all Subscriptions that were previously added to it and that may be added to it in the future. Forgetting the last part of the previous sentence can lead to bugs, so it’s worth repeating: If you call unsubscribe() on a CompositeSubscription, any Subscriptions added to the CompositeSubcription from that point on will also be unsubscribed.

Calling Subscription.unsubscribe() on an Observable, however, does not guarantee that your Activity will not be leaked. If you create an Observable in your Activity using an anonymous or (non-static) inner Observable.OnSubscribe function object, that object will hold an implicit reference to your Activity, and if the Observable.OnSubscribe function object lives longer than your Activity, then it will prevent the Activity from being garbage collected even after it has received a call to onDestroy().

For example, the code snippet that demonstrates how an Observable could emit HackerNews Storys from the previous chapter, would, if run inside an Activity, cause a memory leak:

Observable.create(new Observable.OnSubscribe() {

@Override

public void call(Subscriber<Story> subscriber) {

if (!subscriber.isUnsubscribed()) {

try {

Story topStory = hackerNewsRestAdapter.getTopStory(); //3

subscriber.onNext(topStory);

Story newestStory = hackerNewsRestAdapter.getNewestStory();

subscriber.onNext(newestStory);

subscriber.onComplete();

} catch (JsonParseException e) {

subscriber.onError(e);

}

}

}

})

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io());

Recall that the code running inside of the call() method is running on an I/O thread. Because of this, we are able to call blocking methods like HackerNewsRestAdapter.getTopStory(), without worrying about blocking the UI thread. We can easily imagine a case where this code starts to run on an I/O thread, but then the user closes the Activity that wanted to consume the data emitted by this Observable.

In this case, the code currently running in the call() method is a GC-root, so none of the objects referenced by the block of running code can be garbage collected. Because the Observable.OnSubscribe function object holds an implicit reference to the Activity, the Activity cannot be garbage collected until the code running in the call() method completes. Situations like this can be avoided by ensuring that the Observable.OnSubscribe object is an instance of a class that does not have an implicit or explicit reference to your Activity.

Avoiding Re-querying for Data Upon Configuration Changes

Querying a data source can often be an expensive operation. Because of this, the Android SDK has a set of classes that help developers avoid having to re-query a data source simply because of a configuration change: Loader and LoaderManager. These classes help us avoid what I shall call the “re-query problem,” the problem of having to re-query a data source simply because of a configuration change. Showing that RxJava offers us a cleaner, more flexible method for handling asynchronous data requires that I show that using RxJava also provides us with a solution to the re-query problem.

There are at least two ways that we can use RxJava to solve the re-query problem. The first way requires that we create Observables that use the Loader classes to fetch data asynchronously. This is the approach that I take in my TDD-based HackerNews client. The second way of solving the re-query problem is to a) ensure that Observables survive configuration changes and b) use the cache or replay operators to make those Observables emit the same items to any future Observers. This approach is suggested by Dan Lew in the last part of his Grokking RxJava article series.

Using cache or replay with Observables that Survive Configuration Changes

Let’s start by examining the approach suggested by Dan Lew. With this approach, the Observable that emits the data to be used by an Activity must be able to survive configuration changes. If the Observable is garbage collected or made inaccessible as a result of a configuration change, then the new Observable that’s created by the re-created Activity will have to perform the same data-loading operation to access the data it needs to perform its responsibility.

There are at least two methods of ensuring that an Observable survives orientation changes. The first method is to keep that Observable in a retained Fragment. The second method is to keep the Observable in a singleton.

As long as an Observable survives an Activity‘s configuration change, RxJava provides several operators that save us from having to re-query a data source after a configuration change: the cache and replay operators. These operators both ensure that Observers who subscribe to an Observable after that Observable has emitted its items will still see that same sequence of items.

The items that are re-emitted for future Observers, moreover, are obtained without re-querying the data source the Observable initially used to emit its data stream. Instead, the items that were emitted are cached in memory and the Observable returned by the cache and replay operators simply emits the cached items when future Observers subscribe to that Observable.

Because the cache and replay operators modify Observable behavior in these ways, the Activity utilizing this Observable can unsubscribe from it when that Activity is being destroyed because of a configuration change. It can then resubscribe to that same Observable without worrying that it missed any items that were emitted while it was being re-created and without causing the Observable to re-query the data source it originally used to emit the items of its data stream.

Building Observables on Top of Loaders

As stated previously, there is another way of using RxJava without being forced to inefficiently reload data because of a configuration change. Because of the flexibility with which Observables can be created, we can simply create Observables that utilize Loaders to fetch data that an Observable will emit to its Observers. Here is what that might look like:

private static class LoaderInitOnSubscribe implements Observable.OnSubscribe<Story> {

//...

@Override

public void call(final Subscriber<? super Story> subscriber) {

mLoaderManager.initLoader(LOADER_ID, mLoaderArgs, new LoaderCallbacks<Story>() {

@Override

public Loader<Story> onCreateLoader(int id, Bundle args) {

return new StoryLoader(mContext);

}

@Override

public void onLoadFinished(Loader<Story> loader, Story data) {

subscriber.onNext(data);

}

@Override

public void onLoaderReset(Loader<Story> loader) {}

});

}

}

Recall that Observables can be created with an Observable.OnSubscribe function object. So, LoaderInitOnSubscribe can be passed into a call to Observable.create(). Once it’s time for the Observable to start emitting its data, it will use a LoaderManager and StoryLoader to load the data that it will emit to any interested Observers.

Loaders survive configuration changes and if they have already loaded their data, they simply deliver that data to an Activity that’s been re-created after a configuration change. Thus, creating an Observable that simply emits data loaded by a Loader is a simple way of ensuring that Activitys do not need to re-query a data source upon a configuration change.

At this point, some readers may wonder, “If the Loader and LoaderManager are the classes doing all of the hard work, what’s the advantage of simply wrapping the hard work done by those classes in an Observable?” More generally, readers might wonder why they should prefer RxJava-based methods of handling asynchronous data loading when we have solutions given to us by the Android SDK.

This more general question is one that I answer in the next section. I think that my answer to this general question, moreover, will also answer the reader’s questions about why we might load an Activity‘s data from an Observable that simply wraps Loaders and LoaderManagers. So, let’s turn to examining why RxJava-based solutions provide us with cleaner ways of handling asynchronous data loading in our Android apps.

Why RxJava-based Solutions Are Awesome

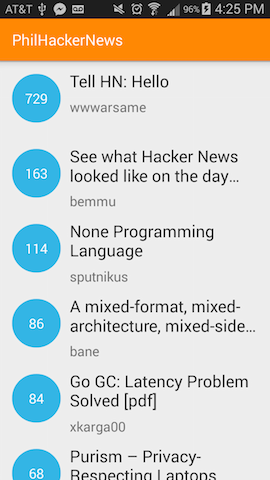

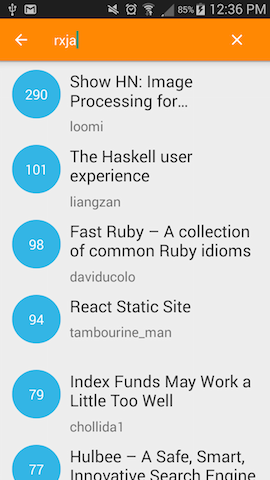

In order to see why RxJava-based solutions for handling asynchronous data can be cleaner than standard approaches, consider the following feature. Suppose the HackerNews app has a SearchView that looks like Figure 2-1:

When the user types into the search widget, the app should make an API call to fetch and display stories that match the search string entered into the widget. However, the app should only make this API call if a) the query string entered is at least three characters long and b) there has been at least a 100 millisecond delay since the user last modified the query string she is typing into the search widget.

One way of implementing this feature would involve the use of Listeners, Handlers, and AsyncTasks. These three components together make up the Android SDK’s standard toolkit for handling asynchronous data. In this section, I compare a standard implementation of the aforementioned search feature that utilizes these components with an RxJava-based solution.

A standard implementation of the search feature might start off with something like this:

searchView.setOnQueryTextListener(new OnQueryTextListener() {

//1

@Override

public boolean onQueryTextSubmit(String query) {

return false;

}

@Override

public boolean onQueryTextChange(String queryText) {

if (queryText.length() > 2) { //2

Message message = Message.obtain(mHandler,

MESSAGE_QUERY_UPDATE,

queryText); //3

mHandler.sendMessageDelayed(message, QUERY_UPDATE_DELAY_MILLIS);

}

mHandler.removeMessages(MESSAGE_QUERY_UPDATE); //4

return true;

}

});

- We start by setting a Listener on the

SearchViewto inform us of any changes in the text entered into theSearchView. - The Listener checks to see how many characters have been entered into the widget. If there aren’t at least three characters entered, the Listener does nothing.

- If there’s three or more characters, the Listener uses a

Handlerto schedule a new API call to be made 100 milliseconds in the future. - We remove any pending requests to make an API call that are less than 100 milliseconds old. This effectively ensures that API calls are only made if there has been a 100 millisecond delay between changes in the search query string.

Let’s also take a brief look at the Handler that responds to the MESSAGE_QUERY_UPDATE and the AsyncTask that is run to hit the API and update the list:

private Handler mHandler = new Handler() {

@Override

public void handleMessage(Message msg) {

if (msg.what == MESSAGE_QUERY_UPDATE) {

String query = (String) msg.obj;

mSearchStoriesAsyncTask = new SearchStoriesAsyncTask(mStoriesRecyclerView, mHackerNewsRestAdapter);

mSearchStoriesAsyncTask.execute(query);

}

}

};

private static class SearchStoriesAsyncTask extends AsyncTask<String, Void, List<Story>> {

private RecyclerView mStoriesRecyclerView;

private HackerNewsRestAdapter mHackerNewsRestAdapter;

public SearchStoriesAsyncTask(RecyclerView storiesRecyclerView, HackerNewsRestAdapter hackerNewsRestAdapter) {

mStoriesRecyclerView = storiesRecyclerView;

mHackerNewsRestAdapter = hackerNewsRestAdapter;

}

@Override

protected List<Story> doInBackground(String... params) {

return mHackerNewsRestAdapter.searchStories(params[0]);

}

@Override

protected void onPostExecute(List<Story> stories) {

super.onPostExecute(stories);

mStoriesRecyclerView.setAdapter(new StoryAdapter(stories));

}

}

There may be a cleaner way of implementing this feature using Listeners, Handlers, and AsyncTasks, but after you see the RxJava-based implementation, I think you will agree that RxJava gives us the means to implement this feature in a way that is probably both cleaner and more flexible than the cleanest version of a non–RxJava-based implementation.

Here is what the RxJava-based implementation would look like:

searchViewTextObservable.filter(new Func1<String, Boolean>() {

//1

@Override

public Boolean call(String s) {

return s.length() > 2;

}

})

.debounce(QUERY_UPDATE_DELAY_MILLIS, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS) //2

.flatMap(new Func1<String, Observable<List<Story>>>() { //3

@Override

public Observable<List<Story>> call(String s) {

return mHackerNewsRestAdapter.getSearchStoriesObservable(s);

}

})

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe(new Observer<List<Story>>() {

//...

@Override

public void onNext(List<Story> stories) {

mStoriesRecyclerView.setAdapter(new StoryAdapter(stories));

}

});

Before I say why I think this implementation is cleaner, let’s make sure we understand exactly what’s happening here:

- First, we apply a

filteroperator. This creates anObservablethat only emits the items of its sourceObservableif those items pass through a filter described by theFunc1object. In this case, theObservablereturned byfilterwill only emitSearchViewtext strings that are more than two characters long. - Next, we apply the

debounceoperator. This creates anObservablethat only emits the items of its sourceObservableif there has been a long enough delay between the emission of those items. In this case, theObservablereturned bydebouncewill only emitSearchViewtext string changes that are separated by a 100 millisecond delay. - Finally, the

flatMapoperator creates anObservableout of the emissions of its sourceObservable. TheFunc1object passed into this operator represents a function that creates anObservablefrom a single item emitted by the sourceObservable. In this case, theObservablecreated emits the list of strings returned by an API call that searches for a HackerNews story based on the query string.

Now that we have a basic grasp of the preceding code, let me briefly say why I think this implementation is cleaner.

First of all, the RxJava-based implementation is less verbose than the standard one. A solution that has fewer lines of code is, all other things being equal, cleaner.

The RxJava-based solution also centralizes all of the code to implement the search feature in one place. Instead of having to jump to the Handler and AsyncTask class definitions to get a handle on how the search functionality works, developers can simply look in one place. This, along with the fact that the code uses operators that have well-established meanings within the functional programming paradigm, makes the code easier to understand.8

Finally, with the RxJava-based solution, error handling is straightforward: Observers will just receive a call to onError(). The standard implementation that uses an AsyncTask, on the other hand, does not have a straightforward, “out of the box” way of handling errors.9

The RxJava-based implementation is also more flexible than the standard one. AsyncTasks must perform their work on a background thread and must perform their onPostExecute() methods on the main thread. Handlers must perform their work on the thread on which they are created.RxJava, through Schedulers, gives us more control over the threads on which asynchronous data is created and consumed.

This control allows us to use Observables both for exposing asynchronous data that is loaded over a network and for an asynchronous stream of text changes that is created by the user interacting with her device. Without RxJava, we are forced to use an AsyncTask for the loading of data over a network and a Handler for working with the stream of text changes. The difference between these two objects, moreover, prevents us from being able to cleanly compose the two streams together like we do with RxJava’s flatMap operator.

Because Observables can have multiple Observers, using RxJava to implement the search functionality also makes it easier to “plug in” additional objects that might be interested in the search events that are triggered by the user’s typing into the SearchView.To see this more clearly, let’s imagine that there was a change in our requirements for implementing the search functionality for our HackerNews client.

Suppose that whenever a user is about to begin a stories search, our HackerNews client will suggest a query from that user’s search history. When the user taps a recent search query, we want the app to execute a search against that query string. With this new feature, a search would be executed if there was a 100 millisecond delay after any characters had been changed in a query string that was at least three characters long and if the user tapped one of her past search query strings. Now, suppose that we want to be able to measure how useful these history-based search suggestions are for our users by tracking their usage with analytics.

In this case, we would still want our stories list to be updated whenever the results from a search have been returned. The only thing we need to change is the conditions under which a search is executed. To do this, we need an Observable that emits the query string of any of the tapped search suggestions.10 Once we have that Observable, we can compose it into our data stream by adding an additional “link” in our chain of operators:

searchViewTextObservable.filter(new Func1<String, Boolean>() {

//...

})

.debounce(QUERY_UPDATE_DELAY_MILLIS, TimeUnit.MILLISECONDS)

.mergeWith(historicalQueryTappedObservable)

.flatMap(new Func1<String, Observable<List<Story>>>() {

//Returns Observable that represents the async data returned from a network call

})

.subscribeOn(Schedulers.io())

.observeOn(AndroidSchedulers.mainThread())

.subscribe(new Observer<List<Story>>() {

//...

});

The mergeWith operator, as its name implies, returns an Observable that emits a stream that results from combining the items of its source Observable and the Observable passed into the mergeWith operator. In this case, the Observable returned would emit a String for the recent search query that was tapped or a String for the query string being typed into the SearchView. Either of these strings would then trigger a network call to execute a search on the query string.

The next piece of our feature that we need to implemente is to track the usage of our history-based search suggestions with analytics. We already have an Observable that emits a string every time a suggestion is tapped, so a natural way of implementing analytics for this feature is to have an additional Observer to this Observable that will record the usage of this feature. The flexibility with which we can add additional Observers to an Observable‘s stream makes implementing this a breeze.

To add multiple Observers to an Observable‘s data, we need to use the publish operator.The publish operator creates a ConnectableObservable that does not emit its data every time there is a call to Observable.subscribe(). Rather, the ConnectableObservable returned by the publish operator emits its data after a call to ConnectableObservable.connect(). This allows all interested Observers to subscribe to a ConnectableObservable before it actually starts emitting any of its data.

Here’s how we could leverage the publish operator to ensure that our analytics are logged and our list is updated whenever the user taps one of her previously executed queries:

historicalQueryTappedConnectableObservable = historicalQueryTappedObservable.publish()

searchViewTextObservable.filter(new Func1<String, Boolean>() {

//...

})

//...

.mergeWith(historicalQueryTappedConnectableObservable)

//...

.subscribe(new Observer<List<Story>>() {

//Update list

});

historicalQueryTappedConnectableObservable.subscribe(new Observer<String>() {

//Log tap for analytics

});

historicalQueryTappedConnectableObservable.connect();

Conclusion

In this chapter, you saw why you should consider using RxJava in your Android code. I showed that RxJava does have two properties that are essential for any effective asynchronous data-loading solution. It can load asynchronous data into an Activity

- without leaking that

Activity - without forcing developers to re-query a data source simply because of a configuration change.

I also compared an implementation of a feature that utilized the standard classes for handling asynchronous data with an RxJava-based implementation and tried to say a little about why RxJava-based implementations are often cleaner and more flexible than standard implementations.

7Fragmented podcast, Episode 6, 50:26–51:00.

8Mary Rose Cook makes a similar point in her “Introduction to Functional Programming.”

9Kaushik Goupal complains about this in his talk “Learning RxJava (for Android) by Example”.

10I realize that getting an Observable that does this is not trivial, but discussing how this would be done in detail would take us too far off topic. The main point here is just to show off RxJava’s flexibility.

The Future of RxJava for Android Development

There is a lot about RxJava that we have not covered. Moreover, we have barely scratched the surface of what RxJava can do to help us write better Android apps. In this last section, I briefly point the reader to some links for further reading and I say a little about some of the current projects that seek to leverage RxJava specifically for helping us write better Android apps.

Further Reading for RxJava

The Reactive Extensions website has a great list of tutorials and articles. There are, however, a few articles in particular that I want to point out here. There are a few important concepts in RxJava that I did not cover here and reading these articles will help you learn these concepts.

The “Cold vs. Hot Observables” section of the RxJs documentation has the best written introduction to hot versus cold Observables that I have seen. Understanding the difference between hot and cold Observables is very important, especially if you want to have multiple consumers of an Observable‘s asynchronous data stream. Dan Lew’s “Reactive Extensions: Beyond the Basics” video also has some very helpful information on the distinction between hot and cold Observables, why this distinction matters, and what operators can be used to transform Observalbes from hot to cold and vice versa. The discussion about hot versus cold Observables is found specifically at 16:30-26:00.

While using RxJava, it is possible to have an Observable that emits data faster than the data can be consumed. This is called “back pressure.” When left unmanaged, back pressure can cause crashes. The RxJava wiki has a helpful page on back pressure and strategies for dealing with it.

RxJava Subjects are another important piece of RxJava that I did not cover. The Reactive Extensions website has a nice overview of Subjects and Dave Sexton has a great article on when it is appropriate to use Subjects.

Future Directions for Android App Development with RxJava

There are several interesting open source projects that are worth paying attention to if you are interested in how RxJava can be used in your Android apps.

The first project is one that I already briefly mentioned: RxAndroid. This library is what provides a Scheduler that’s used with the observeOn operator so that Observers can consume data on the UI thread. According to its git repository’s readme, RxAndroid seeks to provide “the minimum classes to RxJava that make writing reactive components in Android applications easy and hassle-free.” Because this project has a very minimal scope, I expect that much of the interesting work to be done with RxJava for Android app development will come from the other projects I list here.

The second project was originally an offshoot of RxAndroid and it’s called, RxBinding. This project basically creates Observalbes that emit streams of UI-related events typically sent to the Listeners that are set on various View and Widget classes. This project is captained by Jake Wharton.

RxLifecycle is a project helps Android developers use RxJava within Activitys without causing leaks. This library is developed and maintained by Dan Lew and other developers at Trello.

Sqlbrite’s purpose is best captured by its description on GitHub: “A lightweight wrapper around SQLiteOpenHelper which introduces reactive stream semantics to SQL operations.”

This library is backed by the developers at Square. You can learn more about the history of this library by listening to Don Felker and Kaushik Goupal’s interview of Jake Wharton in the seventh episode of the Fragmented podcast.