Measure your open source community’s age to keep it healthy

Your data is telling you what you need to know about turnover and age.

Tree rings (source: Sheila Miguez)

Tree rings (source: Sheila Miguez)

To really grasp a free/open source software project, you need to know how the community that develops and supports it is evolving. Attracting lots of new members will be a reason for celebrating success in a young project — but you should also check whether they stick around for a long time. In mature projects, however, you can afford not attracting many new members, as long as you are retaining old ones. The ratio of experienced, long-term members to recent ones also tells you about the quality of the code and need to support members.

Of the many aspects to explore, two important metrics are:

Turnover

Shows how people are entering and leaving the community. Indirectly, it gives you an indication of how attractive the community is and how well it retains people once they join.

Age

This term refers to “length of time in the project” and measures how long ago each current member joined it. This tells you how many people are available at different stages of experience, from old-timers to newbies.

Together, both metrics can be used to estimate engagement, to predict the future structure and size of the community, and to detect early potential problems that could prevent a healthy growth.

The community aging chart

Both turnover and age structure can be estimated from data in software development repositories. The main source of this information is the source code management repository (such as Git), which provides information about active developers authoring the software. The issue tracking system and the mailing list archives are interesting sources of information as well.

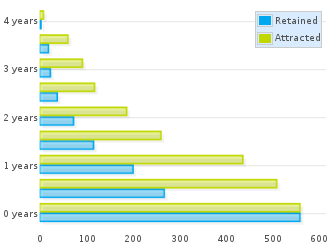

A single chart can be used to visualize turnover and age structure data obtained from these repositories: the community aging chart. This chart resembles to some extent the population pyramid used to learn about the age of populations. It represents the “age” of developers in the project, in a way that provides insight on its structure. For instance, Figure 1 shows the community aging chart for contributors in Git repositories of the OpenStack project in July 2014.

In Figure 1, the Y axis shows different “generations” of project members. The chart is divided into periods of six months, with the oldest generation at the top and the youngest at the bottom. For each generation, the green bar (Attracted) represents the number of people that joined it. In other words, how many people were attracted to the community during the corresponding period — say, first semester of 2010. Meanwhile, the blue bar (Retained) represents how many people in that generation are still active in the community. In other words, how many of those that were attracted are still retained.

One chart, many views

The aging chart can provide insights on many different aspects of the community. Let’s review some of them.

The ratio of the pair of bars for each generation is its retention ratio. By comparing the lengths of each pair of bars, we can quickly learn which generations were most successfully retained, and which ones mostly abandoned the project. For the newest generation, retention will always be 100%, since people recently entering the community are still considered to be active (but that depends on the inactivity period, as I’ll explain in a moment). A ratio of 50% means that half the people in the generation are still retained.

The evolution of green bars tells us about the evolution of attraction over time. Most successful projects start with low attraction, but at some point they become very attractive, and the bars grow quickly. When a project enters maturity, its attraction usually becomes more stable, and can even decline, just because it is no longer “sexy enough” for potential newbies. A large project with declining attraction can remain extremely successful, though.

The evolution of blue bars tells us about the current age structure of the community. If bars in the top are large, but those in the bottom are small, the community is retaining early generations very well, but having difficulties retaining new blood. On the contrary, if bars in the top are small while those in the bottom are large, newcomers are staying, while experienced people have already left. Blue bars can be only as large as green bars (you cannot retain more people from a certain generation than you originally attracted). Therefore, “large” and “small” for blue bars is always relative to green bars.

Different charts for different information

The community aging chart is built taking into account three parameters:

Generation period

People in the community will be charted according to their generation, using this granularity.

Inactivity period

How long we wait before considering that somebody left the community. We don’t know whether anyone really left the community: maybe they are on vacation, or on a medical leave. So we have to choose a certain time period, and decide that “if somebody was not active during the last M months, we consider that person as a departure from the community”. That M is the inactivity period, which is usually equal to the generation period, but could be different.

Snapshot date

The date at which we determine who is retained. Although Figure 1 generated with the current date as the snapshot day, it’s valuable to generate similar charts to show who was retained at various past dates. Comparisons of charts for different snapshot dates say a lot about the evolution of the project’s ability to attract and retain members.

Comparing the community aging chart from the past with the current chart shows the difference in the potential of the project to grow over time. In most development communities, people inactive for a long period are very unlikely to show up again. That means that the sum of the retention bars in the chart snapshotted one year ago is the maximum population that the community is going to have one year later, save for the generations entering during the intervening year.

Sample comparison and some comments

To illustrate the changes in aging over time, Figure 2 shows the community aging chart for a date one year before Figure 1. Both charts show six-month generations and use six month inactivity period as well.

Obviously enough, the 2013 chart has two fewer bars. It lacks the bars corresponding to the two last generations, who still had not joined the project in July 2013. Green bars corresponding to generations more than one year old in July 2014 are exactly the same as those in the chart for July 2014, only shifted by one year. The number of people attracted during a generation does not change when we change the snapshot date.

If we focus now on the one-year-old generation for July 2013 (the third one, counting bottom-up), we can see how it is represented one year later. From a total of about 190 persons attracted, about 100 were still retained in July 2013. That means that in July 2014 we could expect at most 100 persons still retained in that generation. Now fast forward to the future: in the chart for July 2014, about 70 persons are still retained from the (now) two-years-old generation. In other words, the project lost a much higher share of the generation during the first year than during the second one, even if we consider the latter case relative to those that still were in the project in July 2013.

This is a very common finding in most projects: they lose a large fraction of attracted persons during the first year, but are more likely to retain them after that point. This depends not only on the individual inclinations of new project members but also on the policies of the project, and how people enter the community. The retention ratio for the first year usually reflects more than anything how difficult it is to enter the community. The more difficult it is to get in, usually the most engaged people are, and the less likely to leave quickly. But the more difficult it is to get in, the less people in the newer generation are going to be attracted. Therefore, projects with different entry barriers can attract very different quantities of people, but maybe the retained people after one year is very similar. Of course, volunteers and hired developers have different entry/leave patterns too, which influence these ratios.

We can also read the future a bit. Assuming that the current retention rates per generation continue, we can estimate the size of the retention bars for the future, and from it the total size of the community with a certain experience in the project. For example, all those who, one year from now, will still be in the project for a period of two or more years are in the blue bars corresponding to generations currently older than one year. This allows for the prediction of shortages of developers, or of experienced developers.

In fact, any policy oriented to improving attraction or retention can be easily tracked with these aging charts, by defining the ideal charts for the future, and then comparing them with the actual charts when you reach that time.

If you are interested in real examples of community ages charts, check

for the Studies | Demographics menu item in Grimoire Dashboards. You

can find some samples at the Bitergia site.

Public domain instrument illustration courtesy of Internet Archive.