Your critical first 10 days as a leader

Forget the first 100 days. As a leader, your impact begins from minute one.

(source: O'Reilly Media)

(source: O'Reilly Media)

You’ve landed your first true leadership role. You are proud of your new title, excited about the bump in pay, and looking forward to new challenges. As you prepare to step into the new position, you should pause to consider how significant the transition into leadership will be.

Often, people are promoted into leadership roles after they have succeeded at managing projects or excelled at core tasks as an individual contributor. This is particularly true in technology organizations: The best game designer is promoted to be director of game design. There is an assumption that because you are good at doing something, you will be just as good leading a team that does those things. But leadership is different. It isn’t about the tasks as much as it is about the human factors of motivation and engagement. You will need to adopt a new mind-set and deploy new tools.

Why are the first 10 days so critical? Get them right and you are off to a solid start. You will establish leadership momentum that accelerates your impact. Stumble and it could take months or longer to recover. You will find yourself behind the curve, playing catch-up. In your first 10 days you will establish impressions and patterns that endure.

I assume that you are fully invested in making yourself a success. You are taking a step up and may even have pursued this new position aggressively. Your boss, having chosen you from among a number of candidates, is also invested in your success. The unknown is how much of themselves your people will invest in the team’s collective success. Their initial investment decision will be made in this early period and can accelerate, decelerate, or even derail your success.

It is also important to note that leadership is not just about you and your subordinates. People will be assessing where you fit in the constellation of leaders throughout the organization. A great relationship with your boss and subordinates has a halo effect that will benefit you with other units as well as with suppliers, customers, and other stakeholders. There is a multiplier effect.

What follows is a guide to crafting a pragmatic, purposeful plan to optimize your first 10 days.

The Truth about Your New Role

Your elevation into a leadership role does not automatically make you a leader. It does mean that the organization has the expectation that you will lead, but the title does not come with magical powers. The designation of “leader” can be bestowed upon you only by your followers. You are a leader when people willingly follow you. As a leader, your success is not only about you but also about the achievements of the team or unit you lead.

New leaders often fixate on the obvious facets of organizational power: the resources they can deploy, the formal authority that comes with their position, and the access they control. You may, for example, have six direct reports and an extended team of 50 more. The size of your team relative to others sends a signal to the rest of the organization. If you are authorized to sign contracts up to $100,000, for example, that gives you some clout. As you will decide what issues and ideas get advanced to your boss or, perhaps, an investment committee, you are a gatekeeper. In one large manufacturing company I worked with, power was also signaled by square footage and furniture: Office size and decor were strictly allocated by rank. Having two side chairs rather than one was actually significant—and people obsessed over these superficial trappings.

Such positional attributes are indeed important. People need to see that you have the authority to get things done. They are also, in practice, quite limited. A certain amount of authority is handed to you when you walk in the door and taken away when you leave your position. With regard to this power, you likely aren’t that much different from the last person who sat in your seat or the person who will succeed you.

Far more important is your ability to influence others, as this will largely determine the enduring impact you create with your formal authority. Influence is an intangible resource that you carry with you. It’s the “juice” that effective leaders display in abundance. You can build important influence in your first 10 days…and continue to build it over your entire career. Robert Cialdini is an authority on influence and has identified six principles for building influence that are valid across cultures:

- Reciprocity: If you do something for me, I’ll return the favor.

- Commitment and consistency: If people commit to you early, they are wired to be consistent with that commitment (and vice versa).

- Social proof: The first follower is the hardest to get. Once people see one person following you, they are more inclined to join in.

- Liking: Remember Warren Bennis’s advice about being a better person—people we like have more influence over us.

- Authority: The greater your perceived authority from your organizational position or professional expertise, the more influence you will have.

- Scarcity: If you control something that people want, you’ll have influence.

The last two of these are tied to your organizational power, but the first four are much more in your hands. These are the keys to building influence in your first 10 days—and beyond—because they are the foundation of meaningful connection.

Distinguishing leadership as something behavior-based rather than as a right bestowed by title is what makes it possible for you to build your leadership capacity and capability. You undoubtedly come into the role with some skills and abilities; other skills and abilities you will need to work to acquire. Almost everyone has leadership potential, and the truly great leaders I have seen are never satisfied that they have fully realized theirs. They are like master craftspeople who produce beautiful objects but who always see room for improvement. They are continually working toward greater mastery. So, although having an effective first 10 days is essential for a fast start, your overall development as a leader is a marathon, not a sprint. You need to consider your strategy and pacing even before the starting gun is fired.

The other truth is that your effectiveness will result from your ability to integrate your strengths and weaknesses with the needs of your followers. Leadership happens in a context. You must understand that context in order to be the leader that the situation requires. In an article in Harvard Business Review, Herminia Ibarra of INSEAD wrote about a new leader who was open with her team about her vulnerabilities in an attempt to be authentic. The reaction was not what she hoped for—it turned out that the team was yearning for a strong, take-charge leader. You must be highly attuned to both what you bring to the leadership table and what your subordinates, boss, peers, and other stakeholders think you bring and want you to bring.

Your role as a leader is just that: a role. The organization has expectations of how you will conduct yourself; it expects that you will work toward its objectives and carry out its policies even if you don’t fully agree with them. Your followers and peers have expectations, too. Your task is to be your best self in that role using your talents, personality, and proclivities to meet those demands or, at times, to reset their expectations.

This isn’t being fake or inauthentic; it is having the social acuity to be aware of your surroundings and how you can best contribute. If you think about your life, you show up somewhat differently at work than you do at home, or with your college pals, or in a community meeting. We are all multifaceted individuals, and we continually emphasize or deemphasize certain facets of our personalities to fit the setting. You adapt on the basis of what you want to project and the feedback you perceive. Daniel Goleman called this “emotional intelligence,” and his research has shown that emotional intelligence is more indicative of leadership effectiveness than cognitive intelligence. Your leadership challenge is to create the conditions for collective success—and you can do that only when you consider your followers as well as yourself.

How you communicate all this in your first 10 days can set the tone for your entire tenure.

Start Before You Begin

Do not wait until your first day on the job to begin your transition to leadership. The interview process should have given you some view into the expectations of your boss and the organization for you in your new role. Be sure to have as explicit an understanding as possible in advance of your first day.

Make sure you have the answers to questions such as these:

- How does your new boss define success?

- Is she expecting minimal change, a complete overhaul, or something in between?

- Does she have strong opinions regarding any of the people you are about to lead?

- Did any of those people compete for the job you’ve secured?

- How is overall morale?

The answers to these questions can shape your initial agenda. An individual I know was appointed as the acting leader of a large unit in a significantly larger organization. When he asked about the degree of change expected, he anticipated being told to simply keep things “steady as she goes” for a few months. This was an internal promotion, and things were generally going well, in his view. Instead, his new boss informed him that he should prepare the unit for a major change in direction. The permanent head would be hired with a view toward a fresh set of priorities. Had he not asked, this person would have set himself up for failure; he would have sent the wrong signals to the organization, chosen the wrong people for key roles, and made other avoidable mistakes. There is a rather simple moral here for leaders entering new roles at any level: Don’t assume you know what your new boss has in mind for you. Clarify.

Of course, developing an understanding of the lay of the land goes well beyond asking questions of your boss. If you clicked with a peer while interviewing, circle back with that person for coffee or lunch before you start. People are often somewhat guarded during the recruitment process and become more open once they know you are on the team. Find out about the reputation of your new group in the larger organization. Ask about your predecessor—what did he do well, and where is there room for improvement? What are the politics like in the organization? Where are there tensions?

I had just such a lunch before assuming a position earlier in my career. I had been hired into a newly created position to oversee an existing team. There were issues of both quality and productivity and my new boss had too much on her plate to fix it herself. We discussed the likely need to make personnel changes and she told me that I was expected to significantly improve the group’s processes and output. I thought I was going in with my eyes wide open.

But once I sat down with my soon-to-be peer, I quickly realized I did not yet understand the full contours of the situation. He revealed that the creation of my position had been hotly contested in the company: My boss wanted someone with my skills brought in at a level above a counterpart who worked for one of her internal rivals. I was expected to pull rank and assert myself as the authority in this area. Thus there were two problems to fix: one apparent and the other hidden. I was about to be thrust into the middle of an internal political battle not of my own making. Although my boss and I would eventually discuss this frankly after I arrived, I was alerted to the potential minefield only by reaching out to a new colleague. This inside knowledge greatly helped me better navigate my first days on the job.

It may surprise you, but when you walk in the door on Day One you will find forces for you, against you, and on the fence. You enter with a limited perspective on the landscape—an important lesson to carry forward whenever you encounter a novel situation or new stakeholder. Do not assume that all you see is all there is to know: Every organization is a complex, adaptive system with a multitude of formal and informal relationships, power dynamics, and interdependencies. Some are apparent and others are less obvious to a newcomer. As Rob Goffee and Gareth Jones advised in their article “Why Should Anyone Be Led by You?” tune in to the signals that let you know what is happening beneath the surface. As quickly as you can, begin to discern patterns so that the larger system will become more visible. What really drives the organization? Whose views and decisions really matter? Where are the alliances and rivalries?

In the scenario I describe above, I assumed, naively, that everyone would want to improve quality and streamline processes. Who wouldn’t want to be better? I soon learned that some of my new team were quite happy with their current effort and output. The arcane, inefficient processes gave them a sense of control and power. For them, the status quo equaled security; any change was a threat. These subordinates thought my position unnecessary and hunkered down in defensive positions. Others were more engaged and open to new approaches. The rest took a wait-and-see attitude, watching carefully to see how aggressively I would move.

I had little understanding of the larger organization’s politics and the importance, in its culture, of the ability to prevail in internal battles. The boss I thought was terrific was not universally admired. Some wanted her to fail and, by extension, me too. Without an exceptionally supportive peer group and a boss who was skillful at political combat, I might not have survived.

I am familiar with companies where meetings are the settings of robust debate and others where they are essentially ratification sessions for decisions made beforehand. Move uninformed from one culture to the other and you may feel that you have been transported to a different planet. There is a careful dance of knowing when to be a rebel and when to fit in. The micro-culture of a team or department can be changed rapidly; a larger organizational culture takes more protracted effort.

Clearly, the more you can know about the scene you are about to enter, the better. You’ll be able to benefit from those in favor of your arrival and to win over or counter those who oppose you. The majority of people will likely not feel strongly either way; the sooner you can win them over, the faster they will help support what you hope to accomplish.

Go beyond gathering external data by looking inward as well. Think of a person you know whom you consider to be an exceptional leader and one you think is pretty lousy. This can be someone from your current or former work experience, your community, or your place of worship. What matters is that it is someone you actually know and not Nelson Mandela or Genghis Khan. Make a list of what makes the exceptional leader so worthy of being followed. Do the same for the lousy leader, noting what makes him or her so bad. This is a variation of an exercise we use in courses at Harvard. I am going to give you the typical traits—the lists derived there have been pretty consistent over time—but it is still worth compiling your own. Your list is most valuable to you. What we typically see is that people gravitate to individuals who are fair, inclusive, transparent, honest, consistent, clear about their intentions, and able to deliver results. People are repelled by those who are out for themselves, secretive, mercurial, duplicitous, or apt to micromanage.

Next, write a short essay for yourself about why you want to lead. It will help you get into a leadership mind-set. What impact do you want to have? How will you know that it has mattered that you have been the leader of this team? What about leadership scares you? This essay needn’t be polished prose, but it should be as honest and heartfelt as possible. There is no benefit in deceiving yourself. It can be the beginning of a leadership journal in which you record what you learn about yourself and others as you lead. I have recommended this technique to many executive education students. Those who take time each day for reflection have reported that they benefited greatly.

Reflect on what you learn through these exercises and articulate the two or three concrete things you think are most important for people to know about you as a leader and how you will convey them. You likely can’t deliver breakthrough results in the first 10 days but you can demonstrate that, for example, you are fair, inclusive, and transparent. You can set the stage for the results that will come in six months or a year. Write down how you intend to do it.

Consider verbal and nonverbal communication as you plan. In his book Power Cues, public speaking expert Nick Morgan relates that research has shown that people base their understanding much more on your body language, tone, and appearance than on your actual words. Be intentional about where you deliver your message and how you will dress. Your office and other surroundings function as a stage: How will you set the scene? What props will you choose? Even the seat you choose at a conference table sends a signal: Sitting at the head conveys more formal authority than sitting in the center. What do you want to project? If your intent is to loosen up a stodgy bureaucracy, forgoing the traditional seating arrangement can be a subtle, but potent, message. By contrast, if you are taking over a unit in need of direction, plan to go straight for the power chair.

Even as you focus on your first 10 days, don’t forget the marathon analogy. A great runner will consider her abilities in the context of the course, the conditions, and the competitive field and then decide whether to start fast or hang back for a bit. There is no single right answer. You do your best to set yourself up for success by carefully considering the context.

If all this planning feels a bit manipulative, relax. It isn’t. It is being intentional and considered about your choices. As you develop your leadership instincts, these things will become second nature. Until then, you are simply being highly attentive to every detail. Remember when you first learned to drive? In the early days, you had to give conscious thought to every single move. After some practice you were able to operate a two-ton hunk of steel on wheels with one hand and carry on a conversation at the same time. This all takes practice.

First Impressions Matter…a Lot

Just as you, the leader, are taking the measure of people you are meant to lead, so too are the people you want to lead making judgments about you. They don’t know you yet, and they are assessing whether they can trust you. Will you support them? Will you have their back if things get tough? Are they going to like working for you—and do they think you will like having them around? You now are a major influence in their lives because you will have a large hand in shaping how they spend a good number of their waking hours and exert control over their performance reviews and financial compensation. You have the potential to catapult their careers or drive them from the organization.

You have undoubtedly heard the adage that you only get one chance to make a first impression—and that point should remain foremost in your mind in your first 10 days. Research by Mahzarin Banaji and Anthony Greenwald has shown that we all have implicit attitude biases. That is, we make instant judgments about people on the basis of age, sex, race, and other factors that have little to do with their ability to do the job at hand. In the implicit attitude bias test, people are rapidly shown a series of photographs of ordinary-looking people and asked to associate them with certain characteristics. The speed of exposure limits the opportunity for conscious consideration. Over thousands of such tests, the research has shown that everyone carries some biases.

The biases can be explained by both the wiring of the human brain and social influences. The brain’s primary job is to keep us alive. It has evolved a highly attuned ability to judge friend from foe, opportunity from risk. The ability to make those judgments in an instant helped keep our ancestors alive. Social factors emerged as we moved from the realm of saber-toothed tigers to more sophisticated civilization. We all carry a mental image of what a “great X” looks like. Michael Lewis’s book Moneyball chronicled how one Major League Baseball team was able to outperform its rivals by using hard data to evaluate players rather than using the traditional practice of a scout subjectively judging prospects. The traditional idiosyncratic standards were shown to be deeply flawed, yet even when confronted with statistical validation, old-time scouts fiercely resisted change.

For better or worse, the research shows that most people have a deeply embedded Hollywood idea of what a leader looks like: a tall, usually white, man. Harrison Ford is a perfect example. Does this mean that you cannot excel as a leader if you are a woman or short or non-Caucasian? Obviously not; despite the persistence of stereotypes, there are plenty of counterexamples, such as Napoleon and PepsiCo CEO Indra Nooyi. You likely know several from your own experience. However, if you don’t come from central casting you should attend more immediately to the elements of the trust equation in order to overcome implicit attitude biases—like it or not.

After the initial impression, another cognitive heuristic kicks in: confirmation bias. This is the tendency to remember and value that which confirms what we already believe. If people initially perceive you as confident and approachable, their brains will automatically notice information that reinforces that impression. If, instead, they see you as standoffish or difficult, their brains will begin building that case. I recall a former colleague who first impressed me as being tightly wound. Her clothes were professional but austere. Her hair was pulled tightly back. She held an MBA from an elite business school. I thought, “Smart, but an ambitious hard-ass. Probably a stickler, out for herself and tough to work with.” It was almost two years later that we were thrown together on a project and she proved that she was indeed smart. If not for that “accident,” I would not have discovered that she was also fun, creative, and highly collaborative. She turned out to be one of my most supportive colleagues. We remain good friends, but I wish I had made my discovery much sooner.

This is why it is so important to identify the characteristics you want to project and consider how you want to do so, even before you are officially on the job. People shouldn’t discover your talents by accident. As Nike advises, “just do it.” Having a plan will help you overcome any nervousness.

It’s All about Connection

Your actions in the first 10 days will lay the foundation for the perceptions of your leadership capacity and capability. Leadership authority Warren Bennis once said that if you want to be a better leader, you should strive to be a better person. That straightforward advice has more wisdom than its simplicity may at first suggest. What comes to mind when you think of a “good person”? Likely someone who says what she means and means what she says. Someone who treats others with respect. Someone who can be counted on. Let this be your guide along with those “great leader” attributes you noted earlier.

Arriving as a new leader is a bit like entering an arranged marriage for both you and your team. You didn’t pick each other, and many things are uncertain, yet you are destined to spend a lot of time together. The sooner people can come to know you as a person, the more quickly they can make a rational and emotional judgment about you. This is how they decide how much of an investment to make in following you. You want them to offer up as much of their energy, ideas, and commitment as possible.

Mindy Hall has worked with individuals and teams on leadership development for more than two decades. In her book Leading with Intention: Every Moment Is a Choice, she lays out what she calls the “transition triangle,” in which she represents the amount of energy and attention a leader puts into certain activities. In her experience, incoming leaders gravitate toward generating immediate operational results. After all, it is their past results that have gotten them the new job. They invest the least in forging connections. This, she told me, is exactly backward. Forging strong, trust-based connections with your team is the force multiplier that will enable you to lead for peak performance.

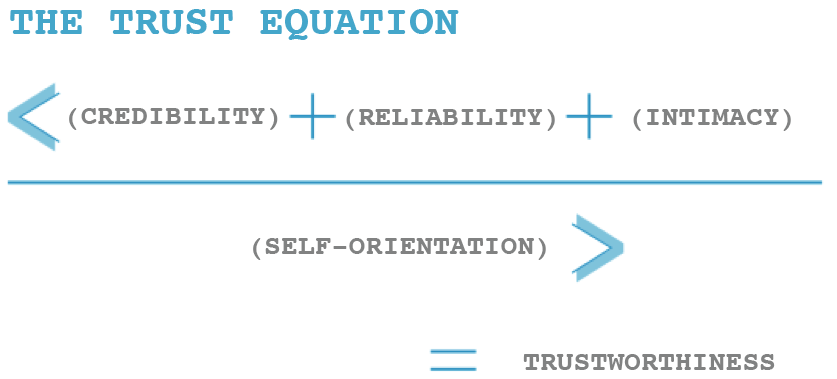

How do you build trust? Charles Green has developed what he calls “the trust equation.” Although Green was writing in the context of consulting, his work is equally applicable to leadership. His equation has three components in the numerator—credibility plus reliability plus intimacy—and one in the denominator—self-orientation. Credibility describes your perceived ability to do the job at hand. Reliability describes your reputation for doing what you say you will do. Intimacy describes your ability to form trust-based relationships. Self-orientation refers to your perceived commitment to yourself versus your commitment to the interests of the larger group. Add up the elements of the numerator and divide by the denominator to arrive at a measure of your perceived trustworthiness. (High numbers in the numerator and a low number in the denominator are preferable.)

So, for example, using a scale of 1–10, you might give yourself a 7 for perceived credibility based on your technical qualifications, a 2 on perceived reliability because you haven’t yet been able to demonstrate much, and a 6 for perceived intimacy if you are generally comfortable meeting new people. This gives you a numerator score of 15. As your self-orientation is still a complete mystery to people, give yourself a 5. Fifteen-over-five results in a trustworthiness score of 3. A perfect score would be 30-over-1 or 30. Surprised at how low it is? Remember that this sample is based on initial perceptions of people who don’t know you well at all. Making positive connections in your first 10 days lets you boost this score significantly by increasing the numerator and, even more important, lowering the denominator.

Building trust takes time. In the short term, however, you can build confidence that your word is rock solid. Something as simple as showing up on time to meetings sends a signal that you take your obligations seriously. Create the conditions to demonstrate your reliability. If one of your subordinates asks you to look over a report, be specific in your commitment to do it: “I’ll be back to you with comments Tuesday morning.” And then deliver right on time. If they don’t ask, give them a task that will inform you and give you the opportunity to deliver timely feedback. A one-page overview of each direct report’s top three current priorities is always a good choice.

As a new leader, you are something of a blank slate to your followers. You may score yourself high on credibility, but what have they got to go on? You have been endorsed by your boss and the organization by being hired, but your team has no direct experience with you. The same is true of reliability, intimacy, and self-orientation. You have the opportunity to shape their assessment either positively or negatively over your first 10 days. Be intentional about doing so and you are more likely to get the results you desire.

The Importance of Being Intentional

I lecture in an intensive, one-week leadership class at the Harvard School of Public Health taught by my colleagues Drs. Leonard Marcus and Barry Dorn. One of the exercises for the participants is to observe two of their classmates. They, in turn, are being observed by two people. No one knows who is watching whom.

By the end of the first day, people are feeling uncomfortable. They realize that they are not simply being watched when they are asking or answering a question or when they are standing at the front of the room. They are being watched all the time: during the breaks, in the middle of a lecture segment, as they enter and leave the room. It is creepy!

Sometime during the second day they begin to get the point: As a leader, you are always being watched. As you take on your new role, people will observe you when you are speaking at a meeting—but they will also notice if you are checking email when someone else is speaking. They’ll see if you ask about someone’s weekend or if you are “all business, all the time.” They will make mental notes about what people you make time for and who can’t seem to get on your schedule.

This scrutiny will never be more intense than in your early days, when first impressions are forming. Subordinates and peers are looking for any clue as to who you are as a person. The more of a puzzle you present, the more likely it is that people will fill in the gaps with their suppositions. In being intentional, you can minimize those gaps. Mindy Hall describes this as being careful and disciplined about your choices moment by moment and being highly aware of your impact. Focus on the outcome you desire and work backward: What are the words, actions, and signals most likely to get you there? Then—and this takes practice—simultaneously be in the moment and watch yourself in the moment to judge whether you are moving things forward, backward, or not at all. What words, actions, and signals are you getting in response to yours? Do people’s words match their body language? How will you adjust on the basis of this feedback?

I recall a participant in a seminar who, unfortunately, had an extreme lack of social radar. He was smart, professional, presentable, energetic, and full of interesting ideas. He also could not stop talking—even to let someone ask a question. When someone did squeeze in a question, he often cut him or her off and delivered a long diatribe as a reply. It was monologue, not dialogue. He was oblivious to social feedback. He even seemed not to notice that the seats near him at lunch were filled last. He had the opportunity to recruit his 50 fellow participants as supporters, investors, or referrals for a new venture he was planning. Instead, for all of his intellectual prowess, good intentions, innovative plans, and drive, he left people with the impression that he was self-obsessed and argumentative. He simply could not connect with people, and thus they would not be led by him.

How could being intentional have remedied this situation? Had he defined success as the number of questions he was asked about his ideas, he would have given more attention to listening than to speaking. Rather than approaching each encounter as a debate to be won, he could have dropped the seed of one of his ideas—“What do you think about…”—and watched to see where the group would take it, intentionally choosing to offer his opinion last. He could have created the impression of being informed and interested, a conversation catalyst, not a boor.

Here is an exercise that will help you build your intentionality awareness—and avoid the “no social radar” trap: For one day before you begin your new assignment, engage everyone you encounter by name wherever possible, smile, make eye contact, and learn something new from them. This means your family, friends, coworkers, the person who serves you at the coffee shop, the parking lot attendant. A day on a business trip is ideal, as you’ll have lots of interactions with people you don’t know. Typically you will get a smile back. The person’s demeanor and body language will change, perhaps subtly, in a positive response because you have shown an interest in them. You will have to listen to learn. Your brain will record this emotional data automatically, but try to make conscious note of it as well in your leadership journal.

After a pre-transition practice run, deploy this technique with each new person you meet in your new job. Be disciplined about making connections: Make eye contact, smile, use the person’s name. You will be distracted as you adjust to fresh surroundings and absorb all that you can about your role, organization, and what lies ahead. No one is going to punish you if you fail to retain the exact release date of the new software package, but they will remember this first encounter for better or worse.

Practice on everyone you encounter, including the receptionist, the executive assistants, and the mail clerk. First, it is a nice thing to do because they are people, too. Second, people in roles like these are often major hubs in an organization’s informal networks. They spread news fast—including their impressions of new people in the company—to their peers as well as to their bosses. Remember Goffee and Jones’s advice about tuning in to subsurface signals? These people are the transmission stations.

Taking Action

One important measure of leadership success is results delivered. In your first 10 days you will not accomplish a major initiative, but you can put a stamp on your role and how you intend to carry it out. You should look to make three meaningful decisions or take three substantive actions. These should have tangible impact, reflect your leadership agenda, and have a solid rationale.

It gets you beyond looking for a single perfect stroke and prevents you from becoming consumed in a frenzy of activity. Be intentional. Choose carefully. Be sure to have your boss’s support and align your plans with her priorities. Also make sure these three are things that you can follow through on; it will undermine your credibility if you make a pronouncement and then have to backtrack. Your specific actions will be dictated by your situation, your style, and the culture of the organization. Below, however, are some examples to guide you.

If the unit you lead is running well, you may opt to deliver something positive quickly: an equipment upgrade the unit has been seeking, for example. This will show the team that you are supportive and committed to providing the resources necessary for success. You may start the planning for a strategic off-site meeting to signal that you will be inclusive in setting future direction.

If, on the other hand, one of your objectives is to increase efficiency, you may direct that all 60-minute meetings be cut to 45 minutes. The one-hour designation largely comes from custom and the default settings of calendars. Require an agenda that includes the objective of the meeting, key decisions to be made, and any expected advance reading or other preparation. Instilling this kind of discipline communicates your intent and your expectations for productivity. Articulate your belief that well-run meetings respect the time of all involved so that no one assumes you are making these changes on a whim. Can you make exceptions to the 45-minute rule? Of course, but only when the agenda truly requires it. Most people will be happy to get the extra time back.

If you have a mandate for major change from your boss, you will want to do something that will get everyone’s immediate attention. One executive I interviewed fired six of his nine direct reports on his first day. That is the most dramatic example I have encountered, and you will not likely have to do anything that drastic. For this person, it worked: Everyone who remained in the workplace clearly understood that change was coming, and coming fast. He engineered a successful turnaround and still leads the organization.

A gentler approach was used by another executive I interviewed. She was brought in for a turnaround and although she was impatient for change, she did not feel that she could “clean house” right away. Rumors were rampant before her arrival. Because her team was globally dispersed and quite large, she sent an email to everyone on her first day. It included a picture of her smiling in order to humanize her. She acknowledged that big changes were needed if the business was to survive and said that she had no illusion that she had all the answers. She looked forward to working with the team to find the answers and make the changes. She concluded with a request for ideas from everyone. Although there were several layers between her and the front lines, ideas began to trickle in. She responded to every single one. The volume increased. She kept responding. Her reputation for being open and responsive quickly spread. She, too, wound up firing numerous people who resisted the new direction, but she also found people who had been repressed by the old management regime. They were full of ideas and energy supporting the changes. She tapped into them, and many were promoted.

Remember to use the techniques discussed in the section headed “It’s All about Connection”: Build trust and influence by being reliable, consistent, and interested. Schedule one-on-one meetings with each of your direct reports during which you can learn more about them and their work. These meetings need not all happen in the first 10 days, but get them on the schedule—and stick to the schedule to show that you value each of them. Walk around and meet as many people at every level as you can. Keep your social radar on high to receive feedback about the messages you are sending. If your team is spread out geographically, use videoconferencing rather than the telephone so that you can project and receive nonverbal cues.

A common question I am asked is how much personal information is appropriate to share with subordinates. It is a good question. You want to be friendly, but your job is not to be their friend. Particularly in your first days on the job, keep it measured. Share positive information that helps you establish rapport while avoiding controversial or weighty topics. An exception is something that could make things awkward or difficult in the office if not addressed. I worked with a professor who had diabetes, and everyone around him knew to watch for signs that his blood sugar was dropping too low. A break would be called in a meeting or someone would bring some cookies to the table so that his condition could be kept in check without making a big deal about it. In my case, I always tell my team early on that for medical reasons I can’t drink caffeine and I have a severe nut allergy. That way no one tries to be nice to the new boss by bringing me a double espresso and a homemade pecan roll. It would be awkward for me and them.

Avoiding Common Mistakes

You will make mistakes. Everyone does. You will recover from the small ones and need to be careful to avoid the big ones. Here are five common first-10-days mistakes that you can sidestep with a little planning and intentionality:

- Failing to prepare and rehearse. Before you try to demonstrate your leadership ability in the bright lights of your new role, practice offstage. Reading about the exercises in this article is not enough. You must actually use them to get any benefit. If you are new to leadership, taking the time to prepare is essential. Lawyers rehearse their arguments; athletes devote hours and hours to hone their skills before actual competition. Work leaders are no different.

- Asserting too much authority too quickly. Unless you face drastic circumstances, be judicious in your use of your formal authority in your first 10 days. Coming on too strong can make you appear self-important or insecure. No one likes a petty dictator. Instead, ask tough questions: “I am concerned about the terms of this vendor contract. Can you tell me the history of how we got here? What are the options for modifying the terms or finding someone new?” This approach conveys your seriousness and intent to change. The advantage is that instead of making your subordinate defensive, this approach involves him in solving the problem. Through measured use of your power, you can build influence beyond your formal authority. Operate under the assumption that no one has all the answers—particularly you—and everyone has part of the answer. This will keep your mind open and your actions inclusive.

- Failing to respect the operational rhythm. Every team, department, and business unit has an operating rhythm that allows it to accomplish objectives. Your arrival will cause some disruption of that rhythm as everyone looks to see what you are like and how you operate. If the unit is functioning well, you want your distraction to be minimal. Look to integrate your approach with the ones that already are producing results. They may have good reasons for doing things a certain way, and you shouldn’t try to fix what isn’t broken. Of course, if the team is dysfunctional, a bit of commotion may be just what it needs. Calibrate your actions appropriately.

- Getting stuck in the weeds. As a leader, you have to grasp the big picture while you understand the details. You may need to temporarily go deep to understand the projects on which your team is working, but be clear to yourself and to them that it is temporary. You need your people to master and manage the minutiae—your job is to create clarity around the larger purpose, meaning, and objectives of the work. Let people know that you will hold them accountable, but that you don’t intend to do their job for them. Remember that “micromanager” makes the “lousy leader” list every time.

-

Missing chances to adjust course. Your first 10 days as a leader are a challenge in rapid iteration. You have to sense what is going right and what could be going better—and to do something about it. Spend 30 minutes each day to reflect in your leadership journal. Use these ritual questions as a guide:

- What did I learn about myself today?

- What did I learn about others today?

- What interaction went particularly well?

- What interaction could have gone better? How?

- What adjustments will I make tomorrow to improve my leadership outcomes?

Getting into the habit of self-assessment and reflection is one of the most valuable things you can do to boost your leadership capacity and capability over your first 10 days…and the next 10 years.

Leading people can be enormously satisfying. It also takes a lot of work. You will need to continually strive to learn more about yourself and the people who work for you. Connect with your people, set the right tone, and take actions that demonstrate your trustworthiness, direction, and intentions. Even in these early days, be thinking about your larger impact and ultimate legacy. How well you do here is important to how the entire organization perceives you, how willing people will be to support you, and whether or not others see you as an enduring presence they want as an ally. Most important, remember that it is not all about you; as a leader, you must set the conditions for collective success. Approaching your first 10 days with the right mind-set, discipline, and commitment to succeed will get you off to a great start.

Recommended Reading from Safari

On Becoming a Leader by Warren Bennis. Bennis’s wisdom endures. He was ahead of his time in understanding how organizations were evolving into flatter, more team-centric environments and, with that, perceiving the need to think about leadership differently. This is a book to come back to again and again. Chapters two and three are particularly relevant to your first 10 days.

“The Power of TouchPoints” in TouchPoints: Creating Powerful Leadership Connections in the Smallest of Moments by Douglas Conant and Mette Norgaard. Conant, the former CEO of Campbell Soup Company, became legendary for using seemingly mundane interactions to form meaningful connections with people throughout the organization. He shows that you don’t have to wait for a big moment to have a big impact.

“What Leaders Do,” video featuring Robert Kaplan in Cultivating Leadership in Your Business. Harvard Business School’s Robert Kaplan is compelling about the need for leaders to admit that they don’t know everything, to welcome contrary views, and to be relentlessly curious.

“Weapons of Influence” in Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert Cialdini. As a leader, you will discover the need to persuade people every day. Cialdini is the foremost expert on persuasion, and his advice is based on research, not gimmicks. It will help you understand and navigate cultural and other challenges you will face.

Leadership and the New Science by Margaret Wheatley. I continually refer to Wheatley’s work when trying to understand and explain complexity and its relevance to leadership. The science in this book is no longer new, but its insights are still highly relevant. It is great for those who prefer hard science to “squishy” leadership books. Read the entire book.

“The Leader’s Triple Focus” in What Makes a Leader: Why Emotional Intelligence Matters by Daniel Goleman. Every leader needs to understand the importance of emotional intelligence, and Goleman’s work is the best source. This chapter, which both distinguishes among and integrates inner, outer, and other focus will help keep you centered in your first 10 days.

Leadership: A Master Class—Authentic Leadership by Daniel Goleman with Bill George. As a leader, you need to find and embrace your values and purpose; they will be your rudder amid turbulence. This introduction to authentic leadership provides sound concepts and practical guidance to get you on your way.