Year Zero: Our life timelines begin

In the next decade, Year Zero will be how big data reaches everyone and will fundamentally change how we live.

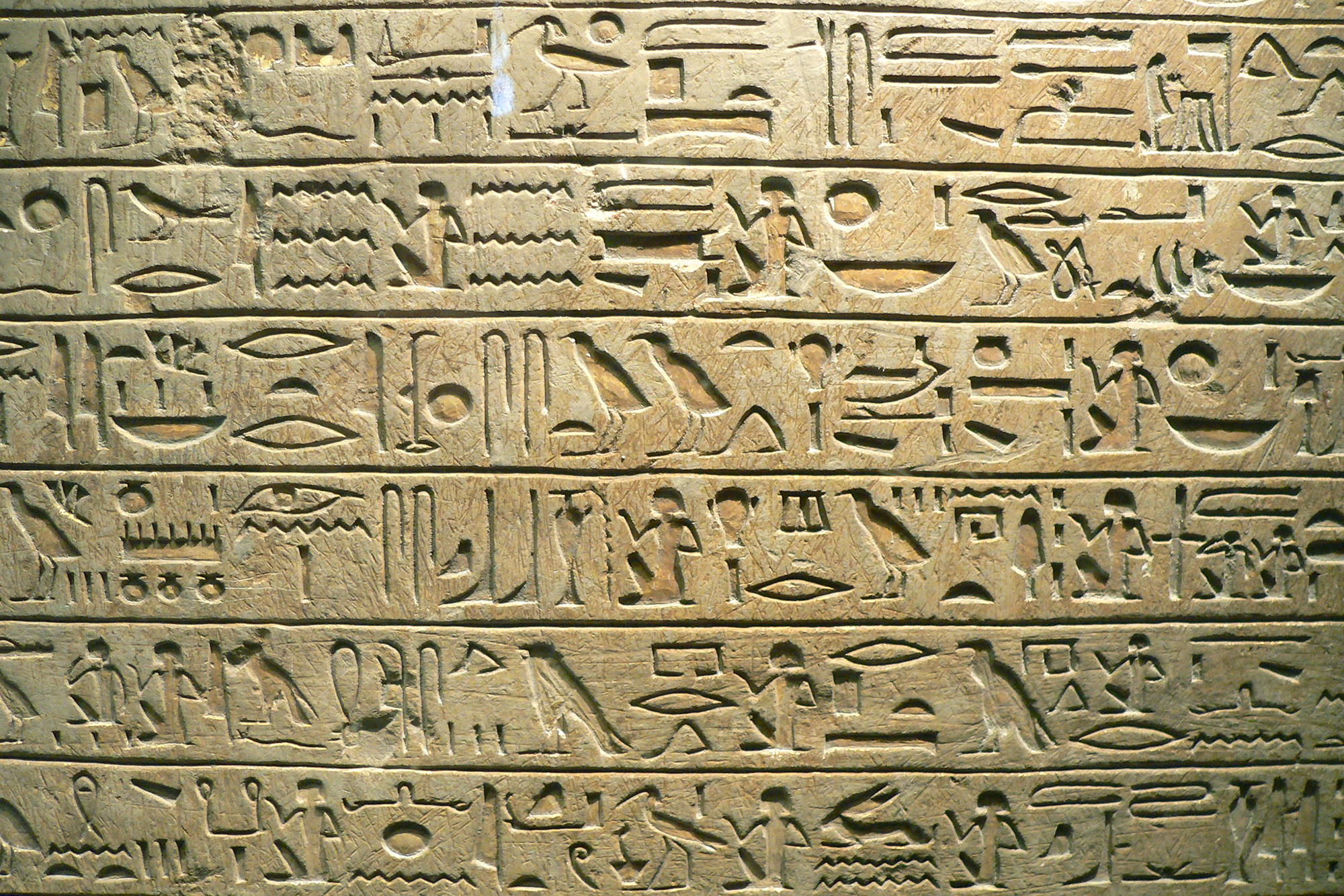

Egyptian Hieroglyphics (source: Anonymous)

Egyptian Hieroglyphics (source: Anonymous)

Editor’s note: this post originally appeared on the author’s blog, Solve for Interesting. This lightly edited version is reprinted here with permission.

In 10 years, every human connected to the Internet will have a timeline. It will contain everything we’ve done since we started recording, and it will be the primary tool with which we administer our lives. This will fundamentally change how we live, love, work, and play. And we’ll look back at the time before our feed started — before Year Zero — as a huge, unknowable black hole.

This timeline — beginning for newborns at Year Zero — will be so intrinsic to life that it will quickly be taken for granted. Those without a timeline will be at a huge disadvantage. Those with a good one will have the tricks of a modern mentalist: perfect recall, suggestions for how to curry favor, ease maintaining friendships and influencing strangers, unthinkably higher Dunbar numbers — now, every interaction has a history.

This isn’t just about lifelogging health data, like your Fitbit or Jawbone. It isn’t about financial data, like Mint. It isn’t just your social graph or photo feed. It isn’t about commuting data like Waze or Maps. It’s about all of these, together, along with the tools and user interfaces and agents to make sense of it.

Every decade or so, something from military or enterprise technology finds its way, bent and twisted, into the mass market. The client-server computer gave us the PC; wide-area networks gave us the consumer web; pagers and cell phones gave us mobile devices. In the next decade, Year Zero will be how big data reaches everyone.

Content as a gateway drug

The battle for our digital lifelog is already well underway. You probably buy into Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Google, Microsoft, or a handful of others for your calendar, your email, and your media. Media was a gateway drug to a walled garden: your content is locked in, and the barriers to entry are simply too huge to leave.

“The reality is that once inside the walled gardens of GAFA [Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon], consumers will see the walls begin to rise. My music is in the cloud, but soon enough, courtesy of the gateway drug of the quantified self movement, my medical records will be in the cloud, my home security will be managed from the cloud, my banking and my energy needs too.

“If a consumer subscribes to one cloud service, then they are very likely to continue with all the extensions of that cloud service platform rather than mix and match. It becomes increasingly inconvenient to remain service agnostic. The dominant players nurture their ‘walled-gardens’ of creative content and other services tethered to their digital formats and devices.” – Jeremy Silver, Digital Medieval.

Why now?

If this sounds far-fetched, consider two things.

- We’re ready for the tech. Ten short years ago, the iPhone didn’t exist. Yet a decade later, we don’t know how to function without a prosthetic brain in our pockets. Today the Leapfrog Leap Band monitors the activity of three-year-olds, giving them rewards for activity and yelling at them if they stop. The Jibo home robot, which recognizes faces and acts as a family’s central tool for coordinating their lives, was so popular that it not only blew past its Indiegogo target, it shut down pre-sales. A BBC survey of futurists predicted that by 2019, many humans would permanently wear a device that records, stores, and indexes every conversation they have.

- The timeline already exists. Far more importantly, the data lives in police records, bank history, and doctor’s visits. It’s tracked by phone companies, mapping tools, and credit card providers. It’s part of your bus pass, your income taxes, and your speeding tickets.

But — and this is a big but — it’s disparate. Nobody has the whole picture.

Where the data comes from

Some of this data we’ll collect ourselves, of course, through wearables and millions of smart devices. Some of it, like bank transactions, we’ll get easily through downloads and programming interfaces. And some of it — particularly that which is secretive, like watchlists, or that which is sold for profit, like credit history — will only be liberated through enlightened legislation.

We’re also at a turning point in human history because we’re digitizing everything. That means copies are free and analysis is effortless. Consider that music has metadata, leaving that industry in tatters, with power moving from publishers to those who can analyze consumption. Digital data changes everything it touches: Affectiva captures and quantifies emotions in real time from facial image processing; Sociometric Solutions does the same with tone of voice.

It’s here, and it’s a moral issue

This will become a flashpoint for digital rights. Others track you; at the very least, you should have access to that data. It’s your life, after all, and as regulation becomes increasingly data-driven we need a sort of data habeas corpus (more specifically, a confrontation clause): I have the right to see the data collected about me by others. In fact, we’ll have to update that right, too: I need the right to see the data my accusers present against me, using the tools of my accuser.

Ultimately, this is a profound social challenge, and one that I believe will become the moral issue of the next decade: nobody should know more about you than you do. Others might understand the data better — your banker understands your finances; your doctor understands your health. But you should be able to look at it because the tools that analyze and visualize it are improving rapidly and becoming agent-based.

Consider that IBM’s Watson went from diagnosing cancer at the level of a second-year medical student to being 40% better than doctors, in a few short years. As those kinds of tools become cheap — or even too cheap to bill for, the way Google is — computers will be as good as your banker and your doctor. But you’ll need your data.

Ann Wuyts explains that new European legislation around digital transparency could hasten this kind of thinking. Belgium’s Bart Tommelein wants to see an annual “privacy return” the same way income tax returns happen. But what format should this take? How do we send individuals only their own data when it is inextricably intertwined with that of everyone else’s? And what tools would enable the average citizen to explore it meaningfully?

What’s behind it?

This permanent life feed is the convergence of two big trends.

Enterprise resource planning (ERP): Most big companies use massive ERP platforms to coordinate their operations. ERP tools manage cash, employees, materials, and the way the entire company runs at scale. While ERP software is often seen as cumbersome and hidebound, it is also the nervous system that lets large organizations function consistently and predictably.

Today’s consumer already has access to a wide range of tools to manage their lives online and offline. Calendaring and messaging, once the domain of enterprise IT, are now so commonplace we take them for granted. Transaction-by-transaction billing is here, and it’s only getting more digital with Paypal, Apple Pay, and the foundations of cryptocurrency. From rentals by owner to dog-walking services to car sharing tools — all the pieces of the collaborative economy are made possible by a software foundation, and that software leaves a digital breadcrumb trail our life feeds can consume.

Armed with a life feed and the tools to analyze it properly, we’re ushering in an era of what Catherine Barr calls “Life Resource Planning”, or LRP, that lets people coordinate their lives both online and offline. It won’t look like ERP any more than the Facebook feed looks like the feed from a Bloomberg trading desk. But it will serve similar functions.

Big data: Despite being a horribly over-used term, big data is a fundamental element of this change. We think nothing of being able to consult the sum of human knowledge in seconds. This has already altered human behavior in significant ways. And computers are only now starting to be able to classify data themselves, forming smart categories and groupings that make it easier to retrieve information.

Big data isn’t really anything new; rather, it’s about the fact that analyzing huge amounts of varied information quickly has now become vanishingly cheap; so cheap, in fact, that we can’t even bill for it, so we subsidize it through advertising.

When we store information, we generally use a unique key — your social security number, for example, or your Costco member ID. But how can we consolidate information across all those sources in a coherent, consistent way?

Fairly easily, as it turns out. Interstellar aside, time is the primary key of the universe. And as long as we’re on our planet, we can pinpoint interactions by longitude, latitude, and altitude.

Knowing those four things is enough to create a basic index of all events in someone’s physical life; for online activity, we might need an IPV6 address or some kind of account, or visibility into the client or browser they’re using. But that’s probably sufficient for most things; machine learning and human intervention can successfully classify the rest of our lives.

But tying that to identity in reliable ways is challenging; it probably relies on intensely personal biometrics, from retina and heartbeat to even more invasive information. Biometric security is terrifying because the ways in which you hack it are terrifying, and because the more personal and invasive it is, the more likely it is to become a dangerously lucrative business.

Alistair Croll’s Strata + Hadoop World keynote on Year Zero.

Some consequences

It’s difficult to speculate from this side of Year Zero, but there are undoubtedly vast consequences for how humanity will change. For example:

- It’s hard to hide. Consider the work of a secret agent today. No more Universal Exports; now it’s “Mr. Bond, I checked Facebook and you’re obviously a spy.” Alibis will change fundamentally, and we’ll see the emergence of forged lives. The need and demand for fake lives will never disappear.

- Hijacking lives. With our lives connected to digital information, they could be hijacked.

- Patterns are obvious. Correlation, alerting, and prediction will seem commonplace. Choosing what to share, with whom, will be a huge consideration. The history of those interactions will itself be both intensely private and hugely revealing — and potentially misleading, since so many interactions can and will be automated.

- Thoughtfulness means less. How excited are you when someone remembers your birthday now that we all have Facebook? With attention a scarce resource, paying attention to them is a sign that they mean something to you. When an agent pays attention for you, remembering something is a sign that someone launched a task, or that they can afford a better agent.

- How do we reinvent ourselves? If everything we’ve ever liked, and everyone we’ve ever met, becomes part of a documented history, how can we rewrite our own stories? How can we escape a stalker or create a new life for ourselves?

- Prediction and over-optimization. When we go beyond predictive to prescriptive analytics, we’ll change how people behave. And that behavioral change will alter the conditions: when everyone goes to the hidden gem of a restaurant, it’ll be packed. To quote Yogi Berra, “Nobody goes there any more; it’s too crowded.” Lutz Finger makes the point that predictive analytics is already maturing fast.

Will it fuel its own growth?

On the one hand, once this timeline gets some data, it will want more. Machine learning is a hungry engine, and we’ll want to feed it, rewarded by ever-better cognition. Given a bit of information, it will infer more; no need to measure UV exposure directly when geographic coordinates, the UV index, and ambient light provide a reasonable proxy.

What’s more, once a few people use it, it’ll infect everyone, one meeting, doctor’s visit, or speeding ticket at a time. Once citizens realize that others know more than they do, and that it’s easy to correct that imbalance, they’ll demand access.

On the other hand, maybe it will plateau. Younger generations already value privacy above cognition. The fear of being judged by peers they don’t even know, for example, is a huge motivator for not sharing. Think about how scary it was to worry about what people in high school would think of your weird shirt, and multiply that by the chance that the photo of you in your weird shirt could become a negatively life-altering meme.

Get ready for real personal agents

With Life Resource Planning a ubiquitous reality, we’ll finally be ready for personal agents. Already Google Now, Siri, and Cortana are shifting how we use information from responsive to anticipatory, interrupting us wisely.

But tomorrow’s agents will go much further, plucked straight from science fiction: mobile learning apps like Lyka resemble the Diamond Age’s Young Lady’s Illustrated Primer. Startup Nara Logics is a personalization engine that wants to “save the world from an overwhelming ocean of data” — which sounds a lot like filmmaker David Cronenberg’s dystopian version of all-knowing personal agents.

An agent with true AI will become a sort of alter ego; something that grows and evolves with you. What rights will these agents have, and how can they be designed to protect us rather than reporting on us? That’s a far broader moral question than I’m considering here, but it’s one that must be considered. Can a personal agent invoke the Fifth Amendment?

The next 10 years

I believe this life feed will shape the next decade of consumer technology. It’s easily a trillion dollars, just as home computers, or the Internet, or smartphones were. And it’s more than just a new market or new industry — it’s the start of a new species. Year Zero is the top of a slippery slope toward a singularity.

When the machines get intelligent, some of us may not even notice, because they’ll be us and we’ll be them. But since technology is never evenly distributed, for those left behind, or saddled with inferior technology, it won’t be a smooth transition.