When you hear hooves, think horse, not zebra

Don't overcomplicate cybersecurity. Focus on building a strong security foundation and go from there.

Stables (source: leeashby1980 via Pixabay)

Stables (source: leeashby1980 via Pixabay)

A month or two ago I was having a discussion with a physician about obscure diseases—commonly referred to as zebras. While I was considering these zebras in the context of effective data mining strategies for medical diagnosis, he made an interesting point. One of the things that they teach new physicians is the phrase “When you hear hoofs, think horse, not zebra.” The principle is quite simple—the odds are the patient has the more common diagnosis than a rare, improbable one. A simple but illustrative example would be the following (stolen from a physician family member):

An adolescent female patient presents with a three-week history of headache, fatigue, and intermittent fevers but was historically healthy. The physical exam was unremarkable and aside from the occasional fevers, the only symptom of note was that she was pale in color. The zebra could have been meningitis or a brain tumor—and the inexperienced practitioner would order thousands of dollars of tests and subject the patient to multiple procedures. But a routine blood count showed that she was simply anemic—the horse—and just needed extra iron. The rule: Think horse without ruling out zebras.

This principle of how we as humans tend to overcomplicate things resonates with me, but for a completely different sector which has featured prominently in the news of late—cybersecurity.

To consider this issue, let’s discuss three similar viruses of the computer variety, also known as computer worms.

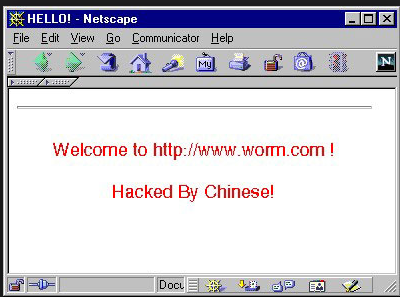

Our first worm is called “Code Red”. This was a Windows virus that could execute arbitrary code once on the host’s system. In addition, the worm would infect a Windows web server and display the following message:

And of course the worm would look to spread and find other infectable hosts in unpatched machines. A patch for this vulnerability had been offered up a month before Code Red’s attacks, but few institutions installed it. This caused substantial headaches and embarrassment to IT departments in multiple sectors.

Our second worm is Nimda. Nimda could transfer itself to a computer five different ways, including email. It became one of the first worms to be able to execute its code even if the host did not open the infected email. Nimda halted federal court workers from accessing court files electronically and the infected court documents had to be cleaned one by one. Nimda, like Code Red, exploited an already-patched Windows vulnerability. Yet, it caused significantly wider damage due to the multiple entry points and rapid spreading.

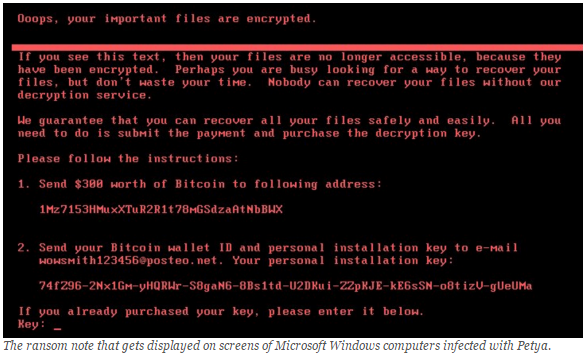

Our third worm is WannaCry. Just as with the last two worms, Microsoft had offered a patch that would have protected against the WannaCry threat. However, there is a bit of detail here that is relevant: a patch was not originally issued for the Windows XP operating system. There was some user frustration with this, but it should be noted that Windows XP was at “End of Support” for over three years at the time of this outbreak (more on this later). WannaCry encrypted files local to the machine and offered up the following message to users:

The user had the choice of paying the “ransom” or losing access to their files permanently. At the same time, the worm would continue to try and spread the infection to other machines that had the unpatched vulnerability. Fortunately, there was a “kill switch” which a smart malware researcher identified and activated and much of the worm’s potential was never realized.

As I was finishing this post, a new ransomware exploit called Petya began infecting systems across the globe. Per TechCrunch, “Everything about this situation indicates that plenty of governments and companies around the world didn’t take WannaCry seriously, failed to patch their systems and are now paying the price.”

As Brian Krebs said, “Organizations and individuals who have not yet applied the Windows update for the Eternal Blue exploit should patch now. However, there are indications that Petya may have other tricks up its sleeve to spread inside of large networks.” This suggests that Petya may simply be the opening salvo, all resulting from poor patching practices.

The common thread behind all of these exploits is that systems were not promptly patched and therefore were exposed to these worms. These were, in fact, preventable problems. But what makes this truly interesting is that the first worms were in 2001 and the last was in 2017. How is it that 16 years later, we are experiencing the same problem?

In the late 1990s and early 2000s as we were building OpenTable, we never considered issues of cybersecurity as we were so focused on hyperscaling the business and the known threats were minimal. However, suffering through Nimda and Code Red got me to wake up. I went to our Board of Directors at OpenTable and briefed them on the emerging threats in the cyber space and how our network could be vulnerable to it. It would directly impact the stability, scalability, and integrity of our business and thus we should invest in making it more secure. I advocated for a security plan focused on doing the security basics well, and it was funded. While security remained an ongoing issue, and I’m sure it worries the OpenTable folks today, it became essentially a solved process and we were able to build on a stable foundation.

The core behind the foundational approach was simple. Patch your systems in a timely fashion, control what can be seen by the Internet and properly permission systems. A user should have the minimum permissions to accomplish what they need. This basic approach remarkably prevents an enormous amount of security exposure. This is the “horse” approach.

This sentiment was echoed in a recent O’Reilly Security podcast, “Dave Lewis on the tenacity of solvable security problems.” Lewis, a global security advocate at Akamai, made the following point which clearly resonates:

Twenty-plus years ago when I started working in security, we had a defined set of things we had to deal with on a continuous basis. As our environments expand with things like cloud computing, we have taken that core set of worries and multiplied them plus, plus, plus. Things that we should have been doing well 20 years ago—like patching, asset management—have gotten far worse at this point. We have grown our security debt to unmanageable levels in a lot of cases. People who are responsible for patching end up passing that duty down to the next junior person in line as they move forward in their career. And that junior person in turn passes it on to whomever comes up behind them. So, patching tends to be something that is shunted to the wayside. As a result, the problem keeps growing.

The moral of the story is that we need to return to the basics to stop this lack of progress in a critical area. When I was the Chief Information Officer (CIO) of the City of Chicago, I spent significant time and effort building out a cybersecurity program. Sadly, at all levels of government that is an area that remains understaffed, underthought and under-resourced. As we are innovating and moving to more digital systems, it is one of the most critical issues that government needs to reckon with.

Despite the obvious benefits of a horse approach to security, as CIO I was constantly barraged by vendors offering highly specialized systems for very specific use cases. I refused to make these types of zebra expenditures when I couldn’t even cover for the horse. So, we started a program focusing on the foundation, and building from there when practical.

Agencies need to consider these basic cyber hygiene steps as a foundation for making critical progress:

- Stay current on patching and make it a departmental/agency priority—it is boring but it is effective.

- Properly permission systems with the minimum permissions necessary.

- For web traffic, always use SSL. https.cio.gov

- The agency executive needs a senior cybersecurity resource who understands technology.

There is no excuse to allow history to repeat itself. The poor practices of 10 years ago should not continue to torment organizations today, and the most effective way to prevent the cyber attacks of tomorrow is to bet on the horse.