Ten years of OpenStreetMap

OSM is moving out of its awkward adolescence and into its mature, young adult phase.

Next to GPS, the most significant development in the Open Geo Data movement is OpenStreetMap (OSM), a community-driven mapping project whose goal is to create the most detailed, correct, and current open map of the world. This week, OSM celebrates its 10th birthday, which provides a convenient excuse to highlight why its achievements to-date are amazing, unusual, and promising in equal parts.

When the project was begun by Steve Coast in 2004, map data sources were few, and largely controlled by a small collection of private and governmental players. The scarcity of map data ensured that it remained both expensive and highly restrictive, and no one but the largest navigation companies could use map data. Steve changed the rules by creating a wiki-like resource of the entire globe, which everyone could use without hinderance.

The magic of OSM’s early success was not just its timeliness — GPS was becoming affordable, storage was increasingly cheap, and the iPhone was around the corner — but its provision of a read-write canvas where emerging mapping enthusiasts could convert their frustration into action. Maps, of course, are intimately personal, but also overtly political: as a true, citizens’ map of the world, OSM could address that particular paradox — no longer were mapping resources allocated by revenue potential; instead, all one needed was time and a computer connection to add data about their country or their neighborhood.

The communal ethos underlying OSM is much more than a feel-good potlatch: the federated nature of the project provides individuals the means to ensure their communities are represented and made real — such as the mapping efforts in Haiti to assist humanitarian relief, or the efforts focused on China and other countries where some believe that a map of the planet should exist independent of government oversight or permission. These projects, and hundreds like them, are not the efforts of OpenStreetMap; rather, OSM provides the mechanism for individuals and organizations to contribute for their own reasons, on their own terms.

“Did you win your sword fight?”

“Of course I won the sword fight,” Hiro says. “I’m the greatest sword fighter in the world.”

“And you wrote the software.”

“Yeah. That, too,” Hiro says.

– Neal Stephenson, Snow Crash

The street maps of OSM were never intended to be perfect out of the gate, and this incremental approach remains a big part of the simple magic underlying the project’s success. For early OSM enthusiasts, “good enough” was a feature, not a bug; it was also a means, not an end. This unspoken, shared belief system is an artifact of OSMers’ scientific faith in the future of The Map, and belief that it will — due to its openness and decentralization — eventually, be the best map on the planet. For OSM enthusiasts, the question is not “how good is it now?,” but rather “how good can it be, how soon?” The answers always are “the best” and “as soon as possible,” respectively.

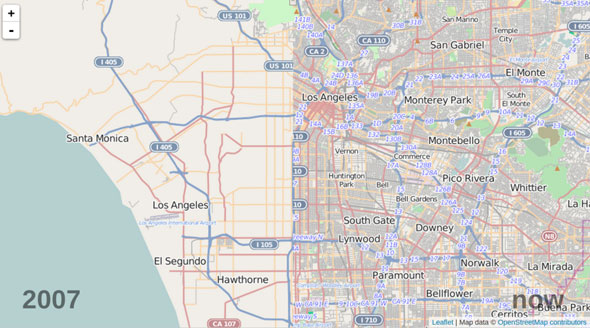

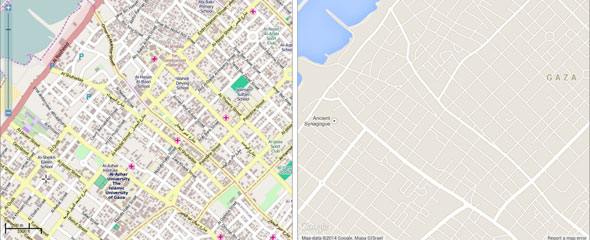

This confidence in The Map is not simply faith over experience. Although you rarely hear the term “velocity of a map,” OSM has a significant speed and direction that justifies the metaphor: two excellent retrospectives best illustrating its rate of enhancement are the Ten Years of Edits video (1:36), where entire countries spring into existence on the rotating globe in elapsed milliseconds, and Martijn van Exel’s more interactive OSM Then-and-Now map that turns the entire world into a split-screen showing the state of OSM in 2007 on the left and 2014 on the right. For a more external, complementary assessment, Geofabrik provides an excellent comparative tool where OSM data can be show against Bing, Google, and other providers.

First they ignore you, then they laugh at you, then they fight you, then you win.

– Mahatma Gandhi

Like a firecracker, the most exciting thing about OSM is its potential. The initiative has in the previous 10 years created a superior display map, but the story has never been about how it looks, but what it is — the data. Unlike any other online map, only OSM allows anyone to access the underlying data that powers the cartography you see. As an example, OSM Mapping company Mapbox is generally ahead of the curve in articulating this critical difference, and have this week begun marketing their product more as a geographic data platform. The emerging message for all consumers of OSM is that OpenStreetMap is not a map, but rather a singular, spatial dataset.

While anyone familiar with the Coastline Paradox will know that new and improved data can always be added to the map, but the map will never be finished. Not because the task is too great, but because there is no end.

Now into its second decade, OSM is moving out of its awkward adolescence and into its mature, young adult phase — specifically the “boring bits” are getting cleaned up on the back end that make it more usable but may never be visible to the eye: nodes are getting connected and turn restrictions added to facilitate navigation, while addresses are being sourced to help with geocoding and place finding. Ultimately, we can expect the next 10 years to focus on enriched data relationships and new, peripheral content that make the map that much more usable and valuable. And while there is little temperature now in the community for machine contributions over human ones (machines just do not have that critical, subjective, local knowledge, it is argued), my money is on contributions from machines, sensors, and bots outweighing those from humans in the very near term.

OSM now has more than 1.5 million registered users, including major mapping and navigation companies. At its heart, OSM is an anarchic and widely dispersed community, but they believe in The Map and the power of a shared commons, and are the reasons for its existence. The project is named OpenStreetMap — one, singular map — for this very specific reason.