Realizing the potential of design

Design is about more than just making things more attractive. This chapter from Org Design for Design Orgs explores the true potential of design.

Gehry building. (source: D. Laird on Flickr)

Gehry building. (source: D. Laird on Flickr)

COMPANIES INVEST IN DESIGN in order to manage the software-driven complexity of their businesses. There’s a sense that design makes things “better,” by making them more attractive, more desirable, and easier to use. However, many, and probably most, of the people responsible for bringing design into their organizations have only a rudimentary understanding of what it can deliver. They perceive design primarily as aesthetics, styling, and appearances.

We ended the last chapter with a Steve Jobs quote about design, so let’s begin this one with perhaps his most famous statement on the matter:

Most people make the mistake of thinking design is what it looks like. People think it’s this veneer—that the designers are handed this box and told, “Make it look good!” That’s not what we think design is. It’s not just what it looks like and feels like. Design is how it works.1

Jobs’ definition is inspiring, but hard to make actionable. For our purposes, we prefer the definition from noted user experience expert Jared Spool, who wrote, “Design is the rendering of intent.” He continues, “The designer imagines an outcome and puts forth activities to make that outcome real.”2 This might seem vague or abstract, but that’s purposeful—it points out that “design” is happening all the time, in a variety of contexts, whether or not we think of it as that. For a company to better deliver on its own intentions, it benefits from incorporating mindful design throughout its activities.

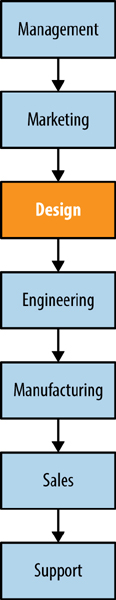

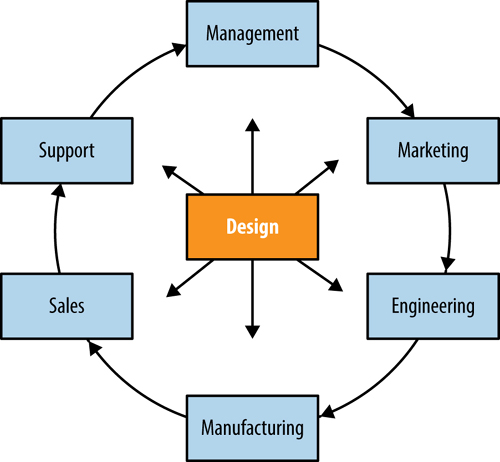

Rob Brunner, founder of product design consultancy Ammunition (best known for their work on Beats by Dre), gave a presentation at the 2016 O’Reilly Design Conference titled “Design Is a Process, Not an Event,”3 where he shared what he saw in the evolution of design. He points out that until recently, design was seen as a step in a chain (Figure 1-1).

He contends that what is now becoming clear is that design is not a standalone event, but a process that works best when infused throughout a product development lifecycle (Figure 1-2).

All Design Is Service Design

As every company becomes a services firm, it follows that the opportunity for design is to make every part of that service experience more intentional. An emerging discipline called “service design” reframes how organizations utilize design. Historically, design has been focused on the creation of things, whether in service of marketing (advertising, branding, packaging) or product (industrial design, software design). Service design applies many of the same practices, but pulls back from this emphasis on artifacts, instead assuming a broader view in an effort to understand the relationships between people (customers, frontline employees, management, partners) and the activities they take part in. Artifacts are no longer considered on their own, but as tools in a larger service ecosystem.

At the heart of service design is the customer journey. Mapping these journeys begins before the customer even knows about a company, traces the customer’s interactions with the company across different touchpoints, and ends when that customer moves on from the relationship. This mapping provides an alternative perspective on service delivery from how organizations are typically structured. It reveals that a customer interacts with marketing, sales, product, and support in a manner that’s typically impeded by departmental silos. It also highlights how certain touchpoints get overloaded with poorly aligned interactions. For example, a company might use email:

-

To extend certain product experiences (daily updates, results of saved searches, etc.)

-

For technical or customer support communications

If these messages are not coordinated well, the customer is overrun by email, and may choose to simply ignore that channel altogether, thus inadvertently inhibiting the company’s ability to communicate.

This has implications for organizational structure. For example, many companies have separate marketing and product design teams. However, to a customer, marketing and product are simply points along the same journey, often delivered in the same media—web browser, mobile app, and email—and would benefit from coherence in the team that designs them. The logical conclusion of the journey mindset is that design practices that are currently kept separate—marketing, communication, environments, and digital products—all contribute to a single journey, and ought to be coordinated. Additionally, this mindset shows how design can support things that it typically is not involved with, such as sales and customer support.

This book is not a how-to on service design. For that, we recommend Marc Stickdorn, Markus Edgar Hormess, Adam Lawrence, and Jakob Schneider’s This Is Service Design Doing (O’Reilly, 2016) and Andy Polaine, Ben Reason, and Lavrans Løvlie’s Service Design: From Insight to Implementation (Rosenfeld Media, 2013). Our point is to recognize that contributions from design shouldn’t be limited to marketing and product efforts, but instead infused throughout the entire service. Wherever the customer and your organization interact, that touchpoint will be improved by design’s intentionality, and this has implications on the shape of the design team.

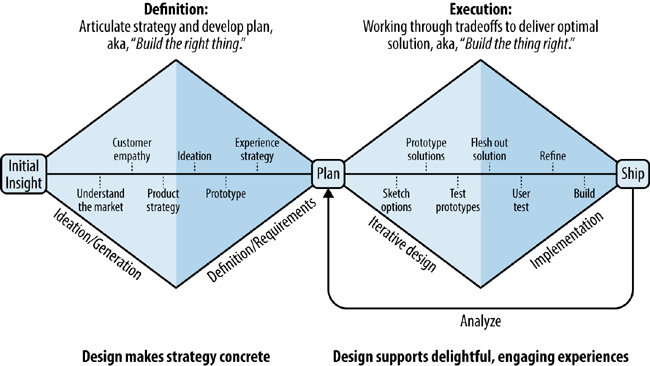

The Double Diamond

To frame design’s ability to contribute broadly, we use the Double Diamond (Figure 1-3), a diagrammatic model of product definition and delivery.

It’s a bit of a simplification, and shouldn’t be construed as a strict process. Still, it serves to depict how designers best approach and solve problems. The first diamond, Definition, addresses the steps needed to articulate a strategy and develop a plan for your offering. The second diamond, Execution, is about implementing that plan.

Too often, project teams settle for linear thinking, where the team leader (typically a product or marketing manager) puts forth an idea that is then taken as the solution, and teams just march toward its implementation. The genius of the diamond shape is that it shows, for both definition and execution, that the team first engages in divergent thinking that broadens the possibility space, before turning a corner and practicing the convergent thinking that narrows in on a specific solution.

Design Defines

In most organizations, designers are not engaged until the second diamond, when strategic and planning decisions have already been made, and their role is to execute on a set of requirements or a creative brief. While service design encourages a broader role throughout the entire customer experience, it may still remain quite superficial and execution oriented. If organizations are going to embrace all that design has to offer, this must involve influencing product and even corporate strategy.

Since at least the advent of scientific management, the predominant mode of business strategy has been analytical. Reduce processes and practices to their elemental components, and squeeze the most out of them. Even product marketing, which should be rooted in creativity and user experience, instead relies on practices such as market segmentation and sizing, surveys to assess consumer sentiment and satisfaction, and product requirements that focus on Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) and the Four Ps (Product, Price, Promotion, and Place).

This stereotypically “left-brained” approach has served business well for quite a while, but has run aground of the connected services economy. Services are predicated on relationships with and between people, a human messiness that these analytical means insufficiently address. What’s called for are more “right-brained” approaches that are holistic instead of analytical, and that are generative instead of reductive. And key to successful human relationships is empathy, a quality distinctly lacking in traditional business practice. Good design practice is an expression of deep empathy, and businesses are realizing that bringing design into the definition conversation (the first diamond) provides better balance in their thinking. At Airbnb, extensive user research was done to build deep personas for Hosts and Guests, which included their respective customer journeys. Airbnb then brought on an artist from Pixar to illustrate key moments in the journey, and these visual storyboards help orient design, engineering, and business around common goals.

Design Makes Strategy Concrete

When strategy focuses on optimization, directives can be written as a set of metrics, such as improving conversion rates or increasing engagement. When it’s about delivering products to market segments, directives are a list of features and the audiences they serve. But when it’s about creating new offerings in an uncertain market context, these reductive approaches fall short. If you remain in the abstraction of spreadsheet formulas or bullet-pointed requirements on PowerPoint decks, four issues arise:

-

There are trade-offs or conflicts within the requirements that are not apparent (say, improving ease of use or task completion, while also empowering users with more functionality), and so a chosen strategy might actually be unworkable.

-

Each stakeholder has their own, unstated understanding of what that strategy means, and their misalignment is not evident until the building process, which proves too late for resolving the conflict.

-

What’s being developed doesn’t accord with the vision stakeholders had in their heads.

-

Internal teams are not motivated by abstractions, and may deliver tepid work that satisfies the requirements, but goes no further.

An architect would never propose a building design without presenting stakeholders a scale model; filmmakers write scripts and draw storyboards before rounding up a crew and committing to a foot of film. Likewise, bringing the design activities of user research, sketching, ideation, and rapid prototyping into strategy work ensures these issues won’t arise. Low-fidelity sketches quickly make apparent shortcomings in an incoherent or incomplete strategy. Even if the strategy is solid, by making it concrete, you ensure that all stakeholders have a shared understanding of the implications of that strategy. If there are issues with the strategy, they get addressed in this early stage, when iteration is cheap, and not during development, when making changes can be quite costly. And by embodying the strategy in a clear vision, project teams have a compelling, motivating goal to attain, a “north star” that encourages them to deliver better than they’ve ever delivered before.

But design shouldn’t be limited to just embodying a strategy established by the business. Design practices should actively contribute to and shape the strategy. Because sketching and ideation are relatively inexpensive, design employs divergent thinking to explore a range of options, feeling them out, or even putting them in front of customers to gauge acceptance. In this way, design brings forth solutions that had not yet even been considered, and does so in a way that can garner meaningful external feedback.

Even with all these obvious benefits, many organizations resist making strategy concrete. By remaining in abstraction as long as possible, hard decisions do not have to be made. Trade-offs do not have to be realized, and everyone can believe that their pet idea will see it through. When design contributes to strategy, it challenges this mindset, and forces stakeholders to commit.

Customer-Centered Planning

In between the two diamonds exists the project plan. The plan typically contains two parts: (a) a vision for where the product is ultimately headed (informed by the strategy work), and (b) a series of steps to realize that vision, sometimes called a roadmap or backlog.

It might seem like a small thing, but how that plan is shaped can be crucial for the offering’s overall success. These plans are typically organized by importance to the business and estimated effort. Features are scored across these two criteria, and then ranked. And then the teams plow through the list.

The shortcoming of this approach is illustrated in the diagram in Figure 1-4, drawn by agile coach Henrik Kniberg:4

When releasing products or services in an iterative and accretive fashion, it’s important to keep in mind the customer’s experience every step of the way. So, even though the first row gets to the ultimate release faster, taking four steps, it does so by sacrificing user happiness at each earlier release. This means, in practicality, users won’t stick around for that ultimate release. They will have moved on to other options.

While it takes five steps to get to the ultimate release in the second row, at every stage there’s a holistic experience. The initial experience might not be what the customer wants, but as the organization learns through successive releases, they deliver more happiness sooner. Also, through that learning, the organization can correct course, and realize a different ultimate delivery (“the convertible”) that serves their customers even better than their original vision (“the sedan”). Design’s role in this process is to bring an empathetic perspective that understands what customers will find desirable, and influence the roadmap to reflect that.

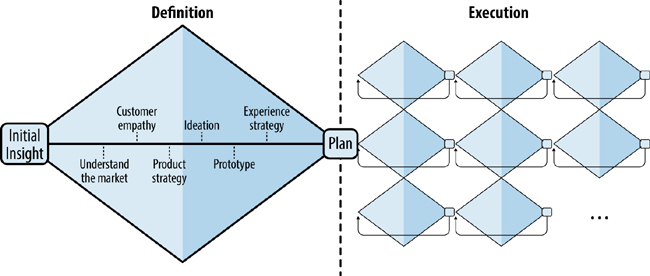

The Bulk of Design Is Execution

We’ve dwelled on strategic and planning matters because these are not widely appreciated, and are essential for design to deliver to its fullest extent. That said, the bulk of an organization’s design effort (80%–90%) will be within that second diamond of execution. A shortcoming of the Double Diamond diagram is that it suggests that for every act of definition, there is an act of execution. In fact, after the creation of a plan, execution occurs iteratively, knocking down elements of the roadmap with each pass (Figure 1-5).

The specific design practices shift when going from definition to execution. When informing strategy, design is more generalized, drawing on user research, sketching, and prototyping. A sketch might represent a software interface, a piece of marketing collateral, or a physical object. Execution brings with it a focus on specific design disciplines. Designing for software, designing for marketing and communications, and designing for physical products are quite distinct practices, and require specialists well-versed in those media.

Bringing Design In-House

The history of business and design is typically one of clients and design firms. Bell Laboratories and Henry Dreyfuss, IBM with Eliot Noyes, Paul Rand and the Eames Studio, Apple and Frogdesign. Design was an outsourced specialty, needed in a tightly defined fashion, usually for logos and products.

At the rise of the Web, most companies handled the need for design through external vendors. They didn’t have capabilities in-house, and weren’t sure it was worth the investment. Twenty years in, it’s clear that we are in a new normal. The shift to networked software and multi-touchpoint services has created a fundamentally chaotic and unpredictable environment that requires continuous delivery.

Design can no longer be a specification that is handed off, built, and never seen again. It needs to be embedded within the strategy and development processes, and its practitioners must be deeply familiar with the company’s mission, vision, and practices. To make this work with an outsourced partner is possible, but very expensive, and raises concerns about an external firm’s alignment with the company’s values and ideals. It’s simply more straightforward to build in-house design competencies that are organizationally and operationally conjoined with functions such as marketing, engineering, and support.

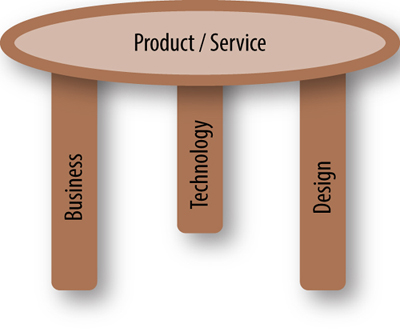

The Three-Legged Stool

This continuous delivery requires changes within product teams. Historically, the ultimate authority in product development lived with someone representing “the business,” such as product marketing, general managers, or product managers, who took in an understanding of market needs, articulated a set of requirements, and gave that to teams to build. For software products, the technology became too complex to locate all decisions in a single product manager—delivering quality work required that people with technical depth also be given authority. This led to teams with joint product and engineering leadership. As we enter a world of connected software and services, the primacy of relationships and need for quality user experience cannot be addressed only through technical and business expertise. Designers should no longer be handed briefs and requirements, but instead be part of the conversation earlier to make sure that their empathetic perspective is represented. The reality of contemporary product and service delivery is a messy one, and requires the productive tension between business, technology, and design. Think of them as the three legs that the offering rests upon (Figure 1-6). If any leg is deficient, what is delivered will be wobbly.

The Expanded Role of Design

Pulling all this together, we arrive at an expanded role for design. For decades, the typical operating mode for design was to receive a brief or requirements from “the business,” limited to the look and feel of the product or the brand impact of a marketing campaign, and execute on that.

The rise of software led to more complex products, and a subsequent realization that many requirements didn’t make sense when users tried to actually operate the system—a lack of empathy led to confusing experiences. Designers created the discipline of user experience to compensate for this shortcoming, developing a set of methods (user research, usability testing, personas, workflows, wireframes) and fostering a user-centered mindset that helped manage this complexity and make it understandable to people.

It then became clear that these practices are useful not just in the execution of a product. As companies improved instrumentation of their experiences, they realized that such approaches drive real business value. They can be used to meaningfully contribute to a service’s definition, and designers found themselves part of the strategic conversations about what should be built. Design had earned its long-sought-after “seat at the table.”

And from that vantage point, it has become clear that the frontier for design is to play a role not only in every stage of development from idea to final offering, but to be woven into every aspect of the service experience from marketing to product to support. The challenge is that most organizations are structured and run in a way that inhibits this potential. In subsequent chapters, we’ll show how to establish, organize, and evolve a design team that can realize this expanded mandate.

1Rob Walker, “The Guts of a New Machine”, The New York Times, November 30, 2003, (http://www.nytimes.com/2003/11/30/magazine/30IPOD.html).

2Jared M. Spool, “Design Is the Rendering of Intent,” User Interface Engeineering (UIE), December 30, 2013, (http://www.uie.com/articles/design_rendering_intent/).

3Robert Brunner, “Design Is a Process, Not an Event,” 2016 O’Reilly Design Conference, January 21, 2016, (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hx8NjT09Phc).

4Henrik explains the diagram in detail here:in the blog post “Making Sense of MVP (Minimum Viable Product)—and Why I Prefer Earliest Testable/Usable/Lovable” (http://blog.crisp.se/2016/01/25/henrikkniberg/making-sense-of-mvp).