Overproduction in theory and practice

A hidden pain point in project management.

Factory (source: Pixabay)

Factory (source: Pixabay)

Imagine that you’re part of a three developer team, and that over the next few months you will be working on building features for a new product that has recently started to gain some traction.

Together with the product owner, your team has agreed to work according to the following schedule:

- Each developer will attempt to complete one new feature per week.

- At any point in time, each developer may have up to two features in a work-in-progress (WIP) state, and one feature undergoing code review.

- Once per week, the product owner will create a plan for a new feature for any developer who has fewer than two assigned WIP tasks.

On the release planning side of things, the following goals have been set:

- Each week, one new feature will be publicly released, with a detailed overview published on the company’s blog.

- A queue of six release-ready features will be maintained, so that even if there are some unexpected delays or other hiccups, there will be a consistent flow of new release announcements on a weekly basis.

You all agree that this is a good starting point, even if it needs to be adjusted later.

Overproduction in theory

The first three weeks go according to plan (as they often do in blog posts), and a total of nine improvements are produced. Three of them have shipped, and the rest are running behind feature flippers waiting to be released whenever the product owner is ready. One team member notes that this is an inflection point, and that it may be time to rethink the schedule.

Everyone else on the team is perplexed, because the team has been moving faster than the release pace, and that is taken to be a sign of excellent performance. Why fix what isn’t broken?

The one team member insists upon conducting a thought experiment, and so you and the others play along. The question is… how many new features should be planned per week now that the release-ready buffer is full?

The product owner at first suggests that what we’re doing seems to be working, so we should stay the course. This will make sure that everyone stays busy with new work, and that we stay ahead of the curve incase of any unexpected delays.

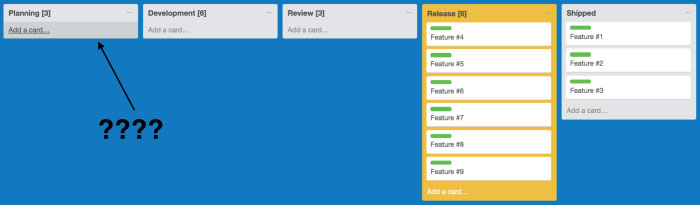

“Ah, but this is what I am worried about!” the concerned developer says. “If we go that route, we will end up with the following board in six weeks unless we start massively overshooting our estimates”:

“What are the red markers on that board?” you ask.

“Blocked features,” the concerned developer replies. “These are features that are ready to move to the next phase of production, but haven’t moved yet because there isn’t an open slot downstream.”

You see this as a good problem to have, rather than a sign of chaos on the horizon.

“Doesn’t this mean that we should just increase the queue sizes at each step to allow us to take on a little more work in each phase?” you ask. “If we are working this efficiently, it means we have some time left over to do more reviews per week.”

“Wait… I see what the problem is. The release pace is the botttleneck!” says the product owner.

The concerned developer smiles. It’s basic math that if you add three things into a bag each week and only take one thing out, the bag will eventually overflow. The size of the bag only affects how long it takes for that to happen.

You suggest to the product owner that maybe more features could be released per week, or that releases could happen more frequently. This idea is quickly shot down for ‘serious business’ reasons, and so other solutions need to be considered.

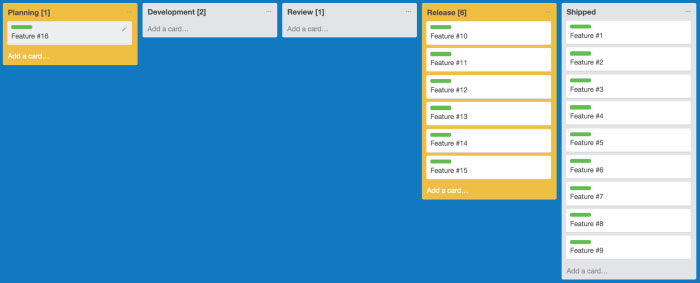

The concerned developer quickly mocks up a new Kanban board reflecting what things would look like if pace was slowed to plan only a single new feature per week for the whole team, rather than one per team member:

The product owner laughs. Then there is an awkward silence for a moment. Suddenly the whole team realizes that the Release and Shipped columns for both boards are the same, even though the amount of WIP tickets has been whittled down to nothing.

A conversation starts on how to possibly sell this idea to the company’s leadership. The concerned developer points out that one of the major benefits is that the average cycle time through this WIP-minimizing system will be much faster than that of the utilization-maximization system shown earlier.

“Suppose you’ve got two bags, each of them with six items to start with. One bag you put three new items in at the beginning of each week, and another you put one new item in. If you randomly remove a single item from each of these bags at the end of every week, which bag is more likely to yield an item that has been in storage longer?” the concerned developer asks.

“The bag with more stuff in it,” the product owner reluctantly admits. “But it’s a not fair comparison, because we don’t randomly select these items. At the start of the week we put only three most valuable new items in, and at the end of the week we take out only the single most valuable item out.”

The concerned developer smirks, and then asks “If that is true, what do you call all the items that keep accumulating in the overstuffed bag?”

This is a riddle worth ruminating on. But just as you start thinking about it, your alarm clock rings, and you are abruptly dropped back into reality. What a strange dream this was…

Overproduction in practice

You rush to get ready and make your way to work. You’re six weeks into the project, and All Is Not Well. In the first three weeks, things did go perfectly—just as in your dream. But then everyone got log-jammed, and it took weeks before two new features made their way into the release-ready buffer. They missed the cutoff date to be written up by a day, and the next release won’t happen until next week.

The product owner has been under pressure from customer support and the sales team to keep pushing new urgent work into development, and while some effort has been made to respect queue limits, each phase of the production process is slightly overloaded. Developers have been stealing time away from reviews to work on new features, and so there is a ton of work that’s almost ready to move into production that hasn’t quite made it there yet.

A meeting is called to address these issues, and the product owner suggests that the team take a full week to clear pending reviews, to figure out what’s blocking progress on the features that are currently in development, and generally to undo the damage of being pushed beyond their limits.

In exchange for this week of downtime, the development team will be expected to work a few Saturdays to “catch up,” but the product manager promises that this will be a temporary state of affairs.

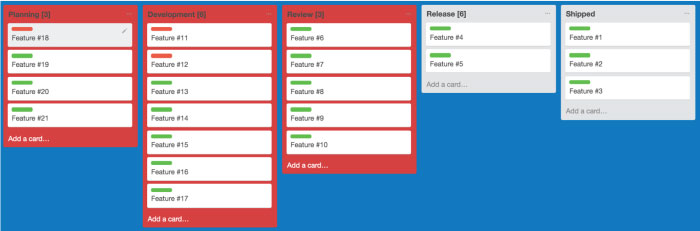

The team pulls together and manages to speed up their progress. In fact, the extra work on Saturdays makes it possible for each developer to max out their own productivity. But then three weeks later, things grind to a halt again:

You stare at the Kanban board in dismay, remembering your weird dream about the downsides of overproduction. You count the cards, and realize that there are now 18 weeks of work queued up in the system, and that it’ll take a couple months before half of it ships. Nearly everything is blocked waiting on downstream open slots, and so everyone is left wondering what to do.

Your product owner calmly suggests increasing the queue sizes at each step in the process, so that things don’t keep getting stuck.

“It’s not that simple,” you say.

Thanks to your dream, you know that the proper solution is to avoid planning features much faster than they can be released. The hard part will be convincing the rest of people in the value chain to see things as you do—but it is worth having an uncomfortable conversation or two if it makes for much more sustainable work.

Editor’s note: Gregory Brown is working on a book about the non-code aspects of software development, called “Programming Beyond Practices.” Follow its progress here.