Out with the industrial economy, in with the service economy

The majority of business growth in the coming decades—new jobs and new businesses—will come from services.

Apis florea nest closeup. (source: By Sean Hoyland on Wikimedia Commons)

Apis florea nest closeup. (source: By Sean Hoyland on Wikimedia Commons)

In today’s world, where ideas are increasingly displacing the

physical in the production of economic value, competition for

reputation becomes a significant driving force, propelling our economy

forward. Manufactured goods often can be evaluated before the

completion of a transaction. Service providers, on the other hand,

usually can offer only their reputations.Alan Greenspan

Industrialization is a phase, and in developed nations that phase

is ending. Growth in developed economies will increasingly come from

services.

The Great Reset

In The Great Reset: How New Ways of Living and

Working Drive Post-Crash Prosperity, Richard Florida points to a shift from an economy based on

making things to one that is increasingly powered by knowledge,

creativity, and ideas:

Great Resets are broad and fundamental transformations

of the economic and social order and involve much more than strictly

economic or financial events. A true Reset transforms not simply the

way we innovate and produce but also ushers in a whole new economic

landscape.

Jeffrey Immelt, CEO of General Electric, agrees:

This economic crisis doesn’t represent a cycle. It represents

a reset. It’s an emotional, raw social, economic reset. People who

understand that will prosper. Those who don’t will be left

behind.

The good news is that although resets are initiated by

failures—sometimes catastrophic failures, like we have seen in the

mortgage system—they also lead to new periods of growth and

innovation, built on new systems and infrastructure.

There’s little doubt that a fundamental economic restructuring

is underway. There will be winners and there will be losers.

An Age of Abundance

As we stand on the verge of a new era, it’s easy to disparage

the old-school industrial economy. But let’s not forget that the

industrial economy gave us an abundance of material wealth we now take

for granted, including many things that were unavailable—and

unimaginable—in previous centuries.

Economist J. Bradford DeLong points out that in 1836, the richest man in the

world, Nathan Rothschild, died of a common infection that would have

been easily curable with modern antibiotics.

In the 1890s, even the richest of the rich could not go to the

movies or watch football on TV, and traveling from New York to Italy

took at least a week.

The material abundance we all enjoy was made possible by an

industrial economy that focused primarily on mass-producing material

goods. The philosophy of mass production was based on Henry Ford’s big idea: If you could produce great volumes of a

product at a low cost, the market for that product would be virtually

unlimited. In the early days, his idea held true, but eventually,

every market gets saturated and it gets more and more difficult to

sell more stuff. By 1960, 70% of families owned their own homes, 85%

had a TV, and 75% had a car.

As markets became saturated with material goods, producers found

a new way to apply the principle of mass production in mass marketing. With a TV in nearly every house,

producers had a direct line to customers. Customers became known as

consumers, because their role in the economy was to consume everything that producers could

make. Increasingly, this producer-consumer economy developed into a marketing-industrial complex

dependent on consumer dissatisfaction and the mass creation of desire for the next new thing.

New technologies of communication have splintered the channels

of mass communication into tiny fragments. It’s no longer possible for

mass marketers to reach out and touch all of their customers at once.

The megaphone is gone. And with the rise of blogs, social networks and

other peer-to-peer communication channels, every customer can have his

own megaphone.

To many mass marketers, this feels like a chaotic cacophony of

voices, and it’s hard to be heard in the crowd. But to most customers,

it’s an empowering feeling to have a voice, to be heard. Even if a

company ignores your complaint, the world will hear, and if companies

don’t respond, they will eventually feel the pain, as customers find

new places to go to get what they want.

The producer-driven economy is giving way to a new,

customer-centered world in which companies will prosper by developing

relationships with customers—by listening to them, adapting, and

responding to their wants and needs.

The problem is that the organizations that generated all this

wealth were not designed to listen, adapt, and respond. They were

designed to create a ceaseless, one-way flow of material goods and

information. Everything about them has been optimized for this

one-directional arrow, and product-oriented habits are so deeply

embedded in our organizational systems that it will be difficult to

root them out.

It’s not only companies that need to change. Our entire society

has been optimized for production and consumption on a massive scale.

Our school systems are optimized to create good cogs for the corporate

machine, not the creative thinkers and problem-solvers we will need in

the 21st century. Our government is optimized for corporate customers,

spending its money to bail out and protect the old infrastructure

instead of investing in the new one. Our suburbs are optimized to

increase consumption, with lots of space for products and plenty of

nearby places where we can consume more stuff—including lots of

fuel—along the way. Our entertainment and advertising industries are

designed to drive demand and keep the whole engine running.

While workers are being laid off in many industries, technology

companies like Facebook and Google are suffering from critical

shortages, struggling to fill their ranks and depending heavily on

talent imported from other countries that place a higher priority on

technical education:

The whole approach of throwing trillions of public dollars at

the old economy is shortsighted, aimed at restoring our collective

comfort level. Meaningful recovery will require a lot more than

government bailouts, stimuli, and other patchwork measures designed

to resuscitate the old system or to create illusory, short-term

upticks in the stock market, housing market, or car sales.

–Richard Florida

We no longer live in an industrial economy. We live in a service economy. And to

succeed in a service economy, we will need to develop new habits and

behaviors. And we will need new organizational structures.

An Emerging Service Economy

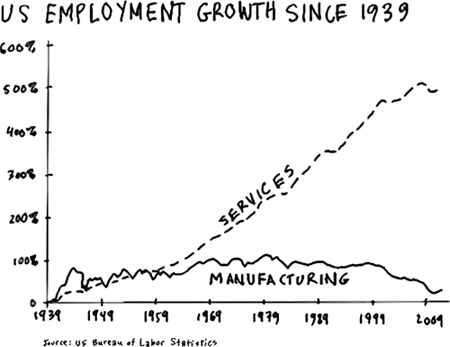

Since 1960, services have dominated US employment. Today’s

services sector makes up about 80% of the US economy. Services are

integrated into everything we buy and use. Nine out of every ten

companies with fewer than 20 employees are in services. Companies like

GE and IBM, which started in manufacturing, have made the transition,

and now make the majority of their money in services.

What’s driving the move to services? Three things: product

saturation, information technology, and urbanization.

Product Saturation

When people already have most of the material goods they need,

they will tend to spend more of their disposable income on services.

Increasingly, the products that companies want to sell us are

optional; they offer not functionality, but intangible things like

status, pride of ownership, novelty, and so on.

And products, we have found, not only make life easier, but

can also be a burden. When you own a house, you have to spend money

to fix the roof or the plumbing. Where’s the fun in that? And moving

can be a big hassle when you have a truckload of stuff to lug along

with you.

A recent study found that Great Britain, where the industrial revolution began, reached “peak stuff”

levels between 2001 and 2003—long before the 2008 recession—and

material consumption has been declining ever since (it’s now down to

the 1989 level).

Information Technology

A post-industrial revolution is delivering a new kind of

abundance: an abundance of information, along with networks and

mobile devices for moving that information around, and much faster

processing, which allows us to do more interesting kinds of things

with the information we have.

Think about how you use the Web. While at first this shift was

driven by the kinds of things we traditionally think of as

information containers, like pages and images, now it has exploded

to include many things that were previously undocumented: your

network of friends and acquaintances, the things you do, the places

you go, the things you buy and what you think about them. Even your

random, throwaway thoughts are being captured in Foursquare

checkins, tweets, status updates, photo and video uploads, and other

kinds of “data exhaust” that you may not even know you’re

generating, simply by using your phone and other devices.

This digital revolution is ushering in new ways to deliver,

combine, and mix up services, resulting in all kinds of enticing

combinations: streaming music, following other people’s book

highlights, renting strangers’ apartments or cars by the day,

negotiating bargain prices from airlines and 4-star hotels, and much

more.

Urbanization

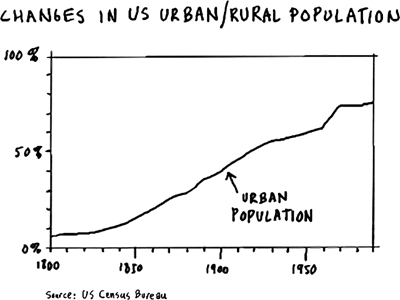

In addition, there is an increasing trend toward urbanization. Throughout the world, city

populations are growing much faster than rural populations. We are

becoming an urban society and living more urban

lifestyles.

Fifty percent of the world’s population today lives on 2 percent of the earth’s

crust. In 1950, that number was 30%. By 2050, it is expected to be

70%.

Why are people moving to cities? Because cities are where the

action is. There are more jobs—and more kinds of jobs—available in

cities, and even when the same job is available in the country and

the city, the job in the city pays more. Urban workers make, on average, 23% more than rural

workers. And the more highly skilled you are as a worker, the more

you stand to gain financially by moving to a large city.

Also, if you happen to get laid off or your company goes out

of business, it’s much easier to find a new job in a city without

having to pick up and move.

As work becomes more complex and more skills are required,

cities become more attractive to companies, too, because that’s

where the skilled workers are. Cities pack a lot of people and

businesses into a relatively small space, which is good for services

companies in several ways.

Space: People living in

small city apartments just don’t have a lot of room for products,

and because they are making more money than their rural

counterparts, they tend to spend more on services. Why take up space

with a washer and dryer when there’s a laundry service right down

the street?

Density: Urban density makes it more attractive for companies

to provide a wide variety of services. For example, a cable company

can wire a city apartment building and serve hundreds of households

for a fraction of the cost to do the same thing in a suburb or rural

area. Taxis find customers quickly in densely packed urban centers. One city block can support several

specialty stores and a variety of restaurants. And in a reciprocal

loop, that wide variety of services makes cities even more

attractive places to live.

Consider the quintessential industrial-age product, the

automobile: for many, it is a symbol of individuality, status,

personality, and freedom. In suburban and sparsely-populated rural

areas, a car provides you with unlimited mobility and choice. But in

a densely populated urban environment, a car quickly becomes more trouble

than it’s worth. A permanent parking space in New York costs more

than a house in many other areas.

Density creates demand for more services, like taxis, limousine services, buses, and

subways. It also creates opportunities for new services. For

example, Zipcar is a car-sharing service that gives customers shared

access to a pool of cars located throughout their city. RelayRide and

Whipcar are peer-to-peer services that allow car owners to rent

their cars to neighbors by the hour or by the day. Uber connects a

network of professional limo drivers with city dwellers, who can

order a car by SMS or mobile phone app; orders are routed to the

nearest available driver, payments are automated, and driver tips

are included, creating a simple, easy, seamless customer

experience.

Cars themselves will increasingly become platforms for

delivering services. In 1995, GM created OnStar, an in-car subscription service that offers

turn-by-turn directions, hands-free calling, and remote diagnostics.

If your car is stolen, GM can track the vehicle, slow it down, or

shut off the ignition remotely. But that’s just the beginning.

Automakers will increasingly be integrating with digital services,

and cars will become platforms for a broad array of apps and

services that will help you lower your fuel costs, stream music,

avoid collisions, find parking, notify you if friends are near, and

a whole host of other things we can’t yet imagine. Ford announced

recently that they are creating an open platform that will allow

tinkerers and developers to electronically “hot-rod” their cars. And

Google is working on cars that will drive themselves. How’s that for

a service?

If a car can be a service, anything can.

The majority of business growth in the coming decades—new jobs

and new businesses—will come from services.

Some people argue that the majority of services growth comes

from low-wage jobs. But according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics, job growth will be led by

health care, followed by professional, scientific, and technical

services, as well as education.