Noah Iliinsky on design at Amazon

The O’Reilly Design Podcast: The importance of intentional thinking, user-centered data visualizations, and separating functionality from implementation.

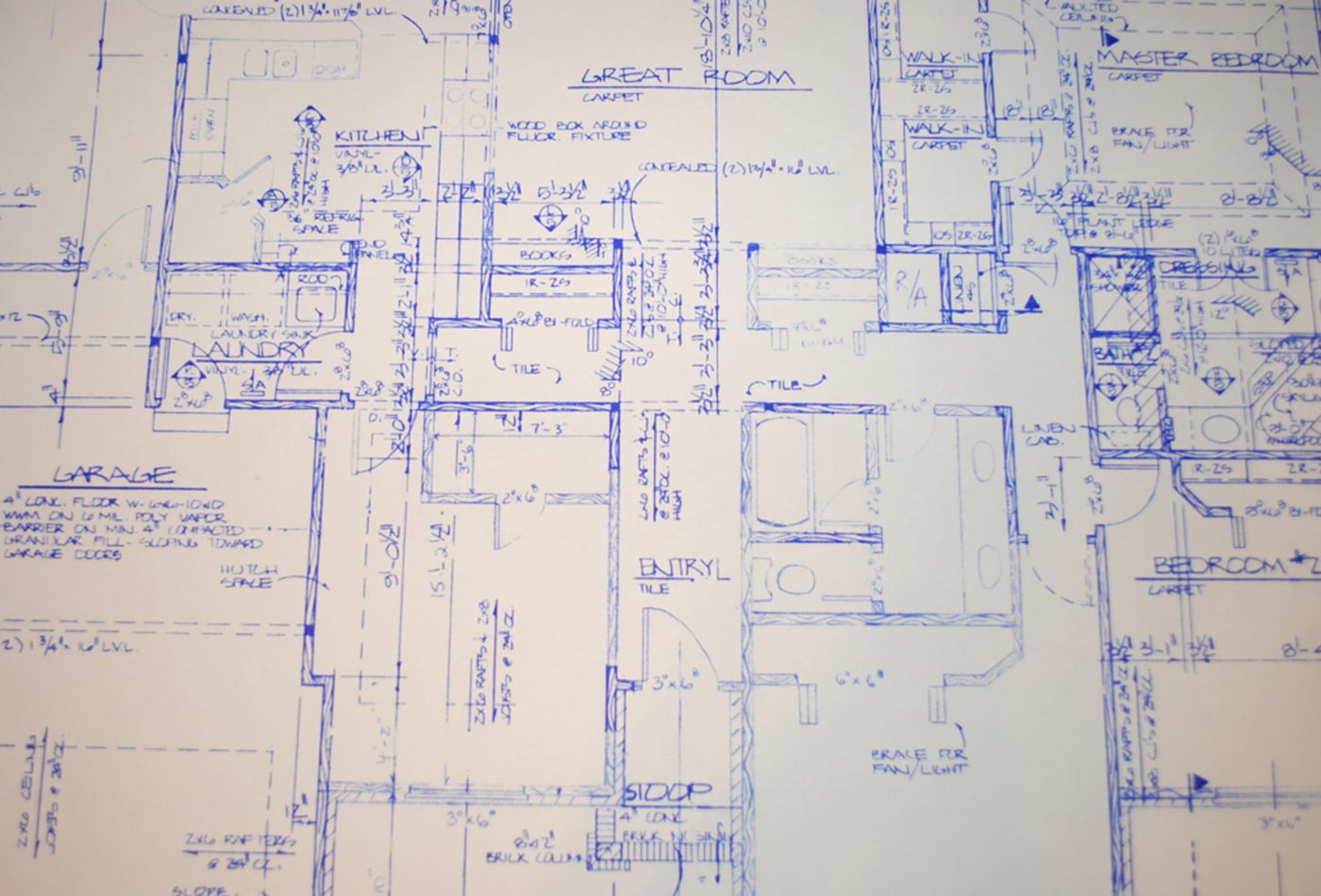

Blueprints. (source: Cameron Degelia on Flickr)

Blueprints. (source: Cameron Degelia on Flickr)

In this week’s Design Podcast, I sit down with Noah Iliinsky, senior UX architect at Amazon’s AWS group, co-author of Designing Data Visualizations, and co-editor of Beautiful Visualization. We talk about how design is organized at Amazon, 17 keys to success, and why being intentional will ensure you are working on the right problems.

Here are a few highlights from our conversation:

Design at Amazon

Typically, design is organized at Amazon in one of two ways. The first category is, as a designer, you would probably work with the storage team, database team, and networking team. You’re sort of the go-to designer for a variety of the product offerings that that larger class of technology has. So, you might be working on two or three products at once for a couple of weeks at a time. Get a new feature out, get a revision out, and then switch to some other product within that class. Those designers tend to sit with the big design pool, all on the same floor. All hanging out together.

The other way that the designers typically work is, there are some groups that are large enough that they have a couple of designers working on a single product. So, for example, Quicksight has a couple of designers. And when a product is large enough or has enough UI work that there’s more than one designer working on it full-time, they tend to sit with the technology and product managers, sort of dedicated full-time within that group.

We’re a young organization when it comes to really building a lot of these UI-based products, but it’s a very exciting time to be here. We have really good, really supportive leadership in the UX space; there’s a real mandate for us to build high-quality interfaces here. So, the designers are part of the very early conversations with product management and with the technology leadership. Typically, it’s the product manager who writes the spec of the product we’re building. But we have processes in place where that spec gets reviewed by designers who get to talk about whether this is the right product, is this going in the right direction, that’s going to be interesting to implement, why are we doing it this way. So, it’s a very exciting time to be here as these changes and these innovations are coming along, and how we do this work and really bring designers to the table in the conversation as products are being not just implemented but conceived.

Data visualizations

I don’t think you need to be able to code or you need to know statistics to create good visualizations. Although absolutely it’s a help, I wouldn’t say, ‘Hey kid, you can’t design visualizations till you learn R.’ That’s just simply not true. There’s plenty of tools that you can use to do it.

The biggest flaw really, I think, with visualizations and how it’s done today is that people lose sight of the user-centered design aspect. So, this is a thing that I have been writing about and teaching ever since I started talking about it and ever since I started writing about it 10 years ago when I was working on my Masters thesis. It’s really bringing the user-centered design approach and this notion of what problems am I really solving with this visualization, what questions am I answering? And the quick-and-easy approach is, we have some data; we’re going to graph it. Done. And that’s a really incomplete process because it doesn’t actually take into account the customer and what are their needs right now and what questions do they need to have answered right now.

I have a pinned Tweet on my Twitter account because a thousand people have said, ‘OK, but what graph should I use?’ This is like asking, ‘What car should I buy?’ I need to know a little bit more about your situation. What shoes should I buy? I need to know more about you. So, I thought, OK, I can compress this entire conversation into one Tweet, which I did.

The Tweet says, ‘Step 5. What graph do I use? 4. What data matters. 3. What questions need answering? 2. What actions do I need to inform? 1. What do I care about?’ And the fun part, the cool part is playing with the graph types, so people want to start with Step 4 or Step 5—I’ve got some data. Let’s graph it.

Maps reveal gaps

If I were to pick one thing I really wanted designers to do differently, I would say to be really intentional about the problems on which you’re choosing to spend your life efforts.

In terms a little less pessimistic and a little bit more grounded in day-to-day, there are two things I think everybody should do more of and would benefit more from. One is, draw your architecture maps. Draw your flow maps. Draw your swim lanes. Draw a diagram or a map of some kind because you can see where you don’t understand the problem when you don’t know how to draw the map. And if you skip the map phase and go right to the interface, I guarantee you it’s going to be a mess. I’ve watched that happen. Even at the level where there’s an icky part in the architecture map and I say, ‘What’s going on there?’ They reply, ‘Oh yeah, yesterday, one of our customers called the PM and said they needed the feature to work this way, so the PM told us we had to do it. So we had to change it.’ And I say, ‘That icky part in the map means you don’t actually understand what the requirement is because the PM doesn’t actually understand what the requirement is because they got it from the customer and they just threw it over the wall.’

The maps reveal where the gaps in your thinking are and if you think you can draw a good interface when you don’t have those requirements defined, it’s just never going to work out. So, use the map as a thinking tool. Use a diagram, it’s crucial.

And the other is one of the ones I stumbled in to accidentally. I accidentally took a class in college. It wasn’t the class I thought it was, but it was in the industrial engineering school at the University of Washington and it ended up being largely about this approach called axiomatic design, which is a theory put forward by Nam Suh at MIT. It’s essentially this notion of separating the required functionality from the implementation—and we’re super bad at that. We go to implementation right away. When I say implementation, I mean if you say a list, now you’re talking about implementations instead of function. And really, really knowing how those are separate gives you so much more flexibility and room for so much more creativity and for the solution you’re designing because as soon as you say list or window or screen or app, all of those things tie you then to this particular notion of implementation, and they remove from your imagination all the other possibilities of the way this particular problem could be solved.