John Whalen on using brain science in design

The O’Reilly Design Podcast: Designing for the “six minds,” the importance of talking like a human, and the future of predictive AI.

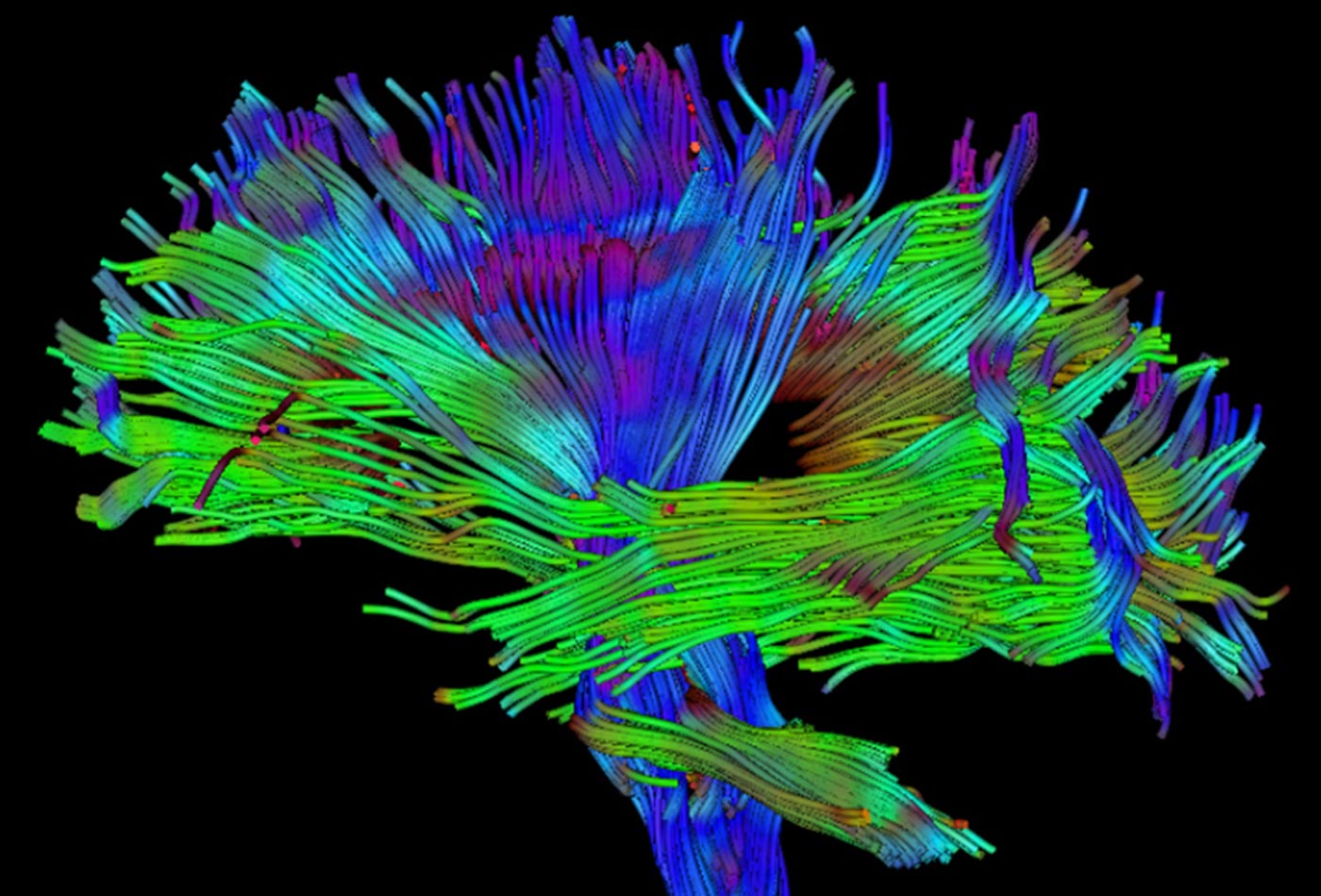

DTI brain tractogram lateral view (source: Aaron Filler, MD, Ph.D., on Wikimedia Commons)

DTI brain tractogram lateral view (source: Aaron Filler, MD, Ph.D., on Wikimedia Commons)

In this week’s Design Podcast, I sit down with John Whalen, chief experience officer at 10 Pearls, a digital development company focused on mobile and web apps, enterprise solutions, cyber security, big data, IoT, and cloud and dev ops. We talk about the “six minds” that underlie each human experience, why it’s important for designers to understand brain science, and what people really look for in a voice assistant.

Here are some highlights:

Why it’s important for product designers to understand how the brain works

I think that by knowing a little bit more about the brain—what draws your attention, how you hold things in memory, how you make decisions, and how emotions can cloud those decisions…the constellation of all these different pieces helps us make sure we’re thinking like our audience and trying to discover their frame of…literally their frame of mind when they’re picking a product or service and using it.

The “six minds” that underlie each human experience

One is vision and attention. The second is memory and all your preconceived ideas and the ways you think the world works. The third is wayfinding—that’s your ability to move around in space, in this case, move around a virtual world. The fourth is language, so the ability to have different linguistic terms. Associated with that is the emotional content there. And, finally, all of that is in service of helping you make decisions and solve problems in your world.

What we look for in a voice-based assistant

We studied how a diverse group of people use Siri, Cortana, Alexa, and Google Assistant, and then we asked, “Well, which one would be your favorite to take home? Which was your personal preference?” A lot of people did pick Google Assistant, which made all kinds of sense because that one did the best at answering questions. But then the second most popular by a wide margin was Alexa from Amazon’s Echo—despite actually being the least successful at answering questions. So, that was intriguing to us and we kind of wondered why.

It turns out that the folks who picked Google Assistant often described what they were looking for from these systems as things like, “I just want the answer fast, just the facts. Give me the answer; I just want to know what’s happening.” And some of the people who preferred Alexa said things like, “Well, it answered the question the way I asked it.” Or, “I like that I can converse back and forth with it. It makes me feel like I’m speaking to a human.” So, there are really humanistic qualities they gravitated to with Alexa.

…We can’t just go out and test our systems to be “percent correct” accurate, we also need to think about this human component. I think that’s the thing I wasn’t necessarily expecting to find from our study. We were curious about this humanistic quality, but we didn’t know how important it was.

How predictive should AI systems be…when does it become creepy?

In our study, we asked questions like, “How much would you like this to know about you?” For example, Amazon knows how often you’ve bought toothpaste, so it could probably predict if you’re running low on toothpaste. It could ask on a random Tuesday, “Gosh, Nikki, would you like some more toothpaste?” And you’re thinking, “How did it know? And where is it looking? And did it have a camera? And who else is in the room?” There are mathematical models that can predict these things quite well.

…There can be all kinds of ways that devices can augment your cognition—and we already do this; we’re already, in some ways, cyborgs, every time we use Google Maps or every time we Google a price to make a decision on choosing something. There are a lot of ways this works, and we are very comfortable with it now. Finding out the weather in advance is actually augmenting what we know, helping us make better decisions.

It can keep doing this; it’s just that we’re not used to it doing it in space and time, and we’re not used to it being as predictive. We’re used to asking it a question and then receiving the answer as opposed to it anticipating that you might need an answer.