Jessy Irwin on making security understandable for everyone

The O’Reilly Security Podcast: Speaking other people’s language, security for small businesses, and how shame is a terrible motivator.

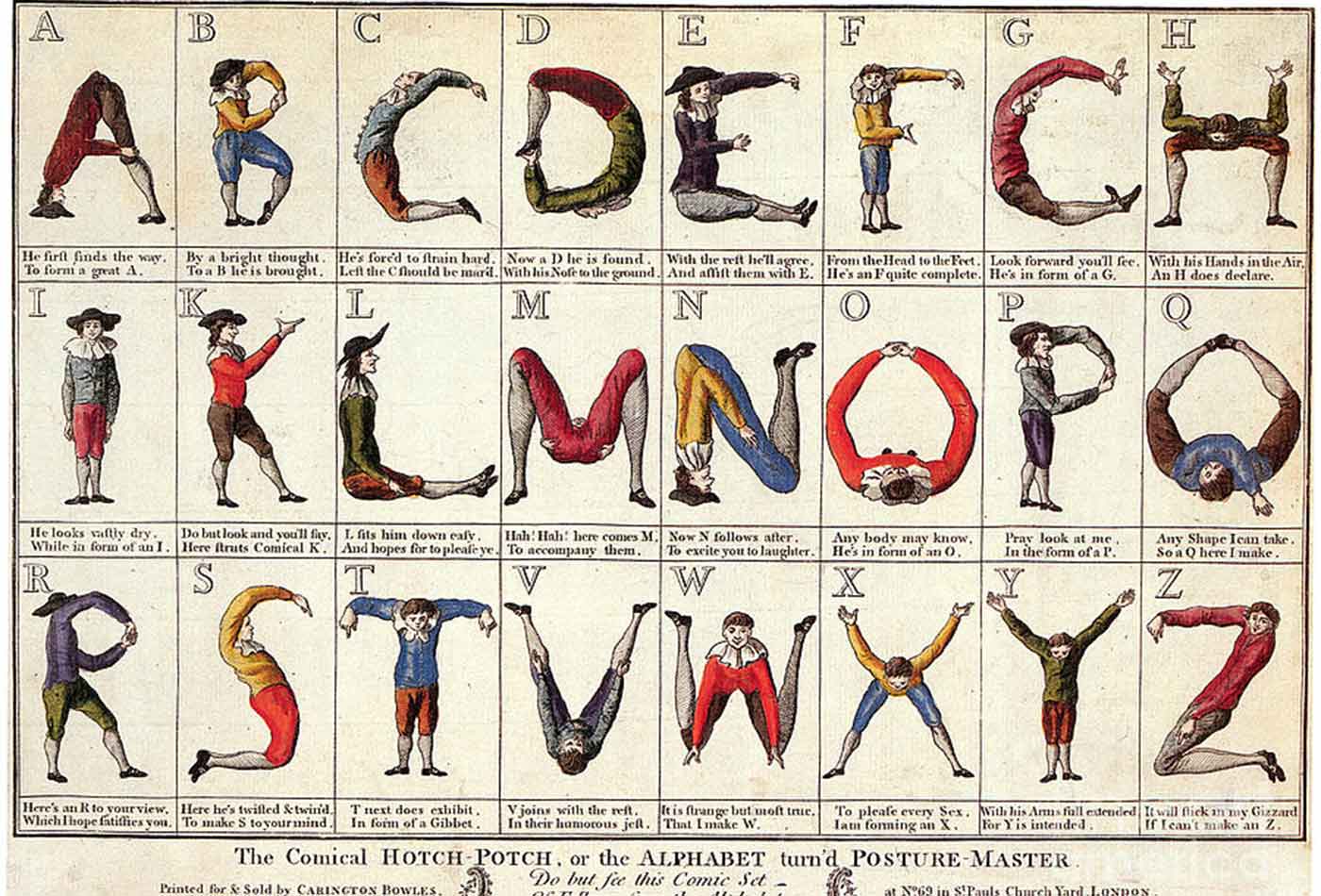

The Comical Hotch Potch, or The Alphabet turn'd Posture-Master, 1782. (source: Carington Bowles on Wikimedia Commons)

The Comical Hotch Potch, or The Alphabet turn'd Posture-Master, 1782. (source: Carington Bowles on Wikimedia Commons)

In this episode, I talk with Jessy Irwin, VP of security and privacy at Mercury Public Affairs. We discuss how to communicate security to non-technical people, what security might look like for small businesses, and moving beyond shame. We also meet her neighborhood gang of grannies who’ve learned how to hack back.

Here are some highlights:

Speaking other people’s language

One of the first things I do when talking to non-technical people is to stop using jargon. The average person doesn’t know what encryption is, and if they’ve heard of the word before, it probably is perceived as something for terrorists, not for them. Password manager is not an intuitive phrase to most people, so I could say, “Well, you need a password app,” and suddenly the whole world becomes a different place for someone who didn’t realize that such a thing exists. It’s important that we communicate with people using their own terms and recognize that the average person is not going to use the word “hacked” the way the security person uses the word “hacked.” Accepting that those moments, which to a professional ear sound like nails on a chalkboard, are going to happen—that completely changed the way I do things.

Your local law office isn’t Netflix or Google

A lot of the people I work with aren’t from tech companies. They tend to be with government organizations or in verticals that maybe use technology but don’t necessarily ship their own technology. It seems like a lot of people in security think it’s completely realistic to expect companies to start security teams, to hire a lot of engineers and run these tools that are five to six figure purchases a year. That’s not going to work for the average business.

These organizations often outsource security services and may not run security tools in-house. They might need security to be managed externally, or they need to focus on configuring tools and processes to allow their small team to build security into the workflow process. Not all of that is going to require engineers, and not every company can or should spend $3 million on security, especially if the organization is a law firm down the street or the mortgage broker around the corner.

Making tools work for people

As an industry, we need to work really hard to make sure our tools are accessible to the average user. Otherwise, the person who handles these tasks potentially only as a part-time IT staffer is not going to be able to use them. If a business has a full-time IT administrator, they might be able to utilize an intern on occasion. Frequently, businesses won’t have a security-minded IT administrator, meaning the person making decisions in a small business won’t necessarily be a security expert.

We need more consumer-friendly tools because then they’re also small business-friendly, which is basically the same audience. We have to focus and be prepared to look at security and say, ‘How do we make this work in half the time? How do we make it work for one dedicated IT person, and then how do we make it work for an organization with a small IT team?’ Then, from there, where do they even start with security? At what point do they need to actually have a security hire, and how can they help that security hire build programs and think in a way that’s going to produce returns for their business?

Moving beyond shame

Making people feel bad when they know they have failed or when they’re trying to get it together is the number one way we set our average consumer or business up for failure. If someone walks in and says, ‘Hey, I’m having a problem with my router. It’s being really weird. I’m not sure what’s up.’ And, some security nerd looks at it and says, ‘Oh, my god. You’re an idiot. Why would you ever configure it this way?’ That’s not just being a bad person; that’s being a really bad ambassador for the kind of work we do. We have to work really hard to say, ‘Yes, that’s okay’ in the right way to positively reinforce good decisions. If we don’t, I really don’t know what the future looks like.